Trimming Rubens' Shadow: New Light on the Mediation of Caravaggio In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index I: Collections

Index I: Collections This index lists ail extant paintings, oil sketches and drawings catalogued in the present volume . Copies have also been included. The works are listed alphabetically according to place. References to the number of the catalogue entries are given in bold, followed by copy numbers where relevant, then by page references and finally by figure numbers in italics. AMSTERDAM, RIJKSMUSEUM BRUGES, STEDEEÏJKE MUSEA, STEINMETZ- Anonymous, painting after Rubens : CABINET The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .20, copy 6; Anonymous, drawings after Rubens: 235, 237 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, Diana and Nymphs hanting Fallow Deer, copy 12; 120 N o.21, copy 5; 239 Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt, N o .5, cop y 13; 120 ANTWERP, ACADEMY Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o.ne, copy 6; 177 Lion Hunt, N o.11, copy 2; 162 BRUSSELS, MUSÉES ROYAUX DES BEAUX-ARTS DE BELGIQUE ANTWERP, MUSEUM MAYER VAN DEN BERGH Anonymous, drawing after Rubens: H.Francken II, painting after Rubens: Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt: Fragment of W olf and Fox Hunt, N o .2, copy 7; 96 a Kunstkammer, N o.5, copy 10; 119-120, ANTW ERP, MUSEUM PLANTIN-M O RETUS 123 ;fig .4S Anonymous, painting after Rubens: Lion Hunt, N o .n , copy 1; 162, 171, 178 BÜRGENSTOCK, F. FREY Studio of Rubens, painting after Rubens: ANTWERP, RUBENSHUIS Diana and Nymphs hunting Deer, N o .13, Anonymous, painting after Rubens : copy 2; 46, 181, 182, 186, 188, 189, 190, 191, The Calydonian Boar Hunt, N o .12, copy 7; 185 208; fig.S6 ANTWERP, STEDELIJK PRENTENKABINET Anonymous, -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/206026 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-25 and may be subject to change. 18 De Zeventiende Eeuw 31 (2015) 1, pp. 18-54 - eISSN: 2212-7402 - Print ISSN: 0921-142x Coping with crisis Career strategies of Antwerp painters after 1585 David van der Linden David van der Linden is lecturer and nwo Veni postdoctoral fellow at the University of Groningen. He recently published Experiencing Exile. Huguenot Refugees in the Dutch Repu- blic, 1680-1700 (Ashgate, 2015). His current research project explores Protestant and Catholic memories about the French civil wars. [email protected] Abstract This article explores how painters responded to the crisis on the Antwerp art market in the 1580s. Although scholarship has stressed the profound crisis and subsequent emigration wave, prosopographical analysis shows that only a mino- rity of painters left the city. Demand for Counter-Reformation artworks allowed many to pursue their career in Antwerp, while others managed to survive the crisis by relying on cheap apprentices and the export of mass-produced paintings. Emigrant painters, on the other hand, minimised the risk of migration by settling in destinations that already had close artistic ties to Antwerp, such as Middelburg. Prosopographical analysis thus allows for a more nuanced understanding of artistic careers in the Low Countries. Keywords: Antwerp painters, career strategies, art market, guild of St. -

De Grote Rubens Atlas

DE GROTE RUBENS ATLAS GUNTER HAUSPIE DUITSLAND INHOUD 1568-1589 12-23 13 VLUCHT NAAR KEULEN 13 HUISARREST IN SIEGEN 14 GEBOORTE VAN PETER PAUL ANTWERPEN 15 SIEGEN 16 JEUGD IN KEULEN 1561-1568 17 KEULEN 20 RUBENS’ SCHILDERIJ 10-11 10 WELGESTELDE OUDERS IN DE SANKT PETER 10 ONRUST IN ANTWERPEN 21 NEDERLANDSE ENCLAVE IN KEULEN 11 SCHRIKBEWIND VAN ALVA 22 RUBENS IN HET WALLRAF- RICHARTZ-MUSEUM 23 TERUGKEER NAAR ANTWERPEN 1561 1568 1577 LEEFTIJD 0 1 2 3 4 ITALIË 1600-1608 32-71 33 OVER DE ALPEN 53 OP MISSIE NAAR SPANJE 33 VIA VENETIË NAAR MANTUA 54 EEN ZWARE TOCHT 35 GLORIERIJK MANTUA 54 OPLAPWERK IN VALLADOLID 38 LAGO DI MEZZO 55 VALLADOLID 39 MANTUA IN RUBENS’ TIJD 56 PALACIO REAL 40 CASTELLO DI SAN GIORGIO 57 OVERHANDIGING VAN DE GESCHENKEN 41 PALAZZO DUCALE 57 HERTOG VAN LERMA 42 BASILICA DI SANT’ANDREA 59 GEEN SPAANSE HOFSCHILDER 42 IL RIO 59 TWEEDE VERBLIJF IN ROME 42 HUIS VAN GIULIO ROMANO 59 CHIESA NUOVA 42 HUIS VAN ANDREA MANTEGNA 60 DE GENUESE ELITE 43 PALAZZO TE 61 INSPIREREND GENUA 44 MANTUAANS MEESTERWERK 65 DE PALAZZI VAN GENUA 48 HUWELIJK VAN MARIA DE’ MEDICI 67 EEN LAATSTE KEER ROME IN FIRENZE 67 TERUGKEER NAAR ANTWERPEN 49 EERSTE VERBLIJF IN ROME 68 RUBENS IN ROME 49 SANTA CROCE IN GERUSALEMME 70 STEDEN MET SCHILDERIJEN UIT 51 VIA EEN OMWEG NAAR GRASSE RUBENS’ ITALIAANSE PERIODE 52 VERONA EN PADUA 1600 1608 VLAAMSE MEESTERS 4 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 ANTWERPEN 1589-1600 24-31 25 TERUG IN ANTWERPEN 25 STAD IN VERVAL 26 UITMUNTEND STUDENT 27 DE JEUGDJAREN IN ANTWERPEN 28 GOEDE MANIEREN LEREN 28 DE ROEP VAN DE KUNST 28 -

Black Tronies in Seventeenth-Century Flemish Art and the African Presence

tronies BlackBernadette van Haute* in seventeenth-century Flemish art and the African presence * Bernadette van Haute is Associate the Maghreb cannot have been very numerous Professor in the Department of Art History, in Antwerp at that time, and it may be that Visual Arts and Musicology at the University all three masters [Rubens, Van Dyck and of South Africa. Jordaens] used the same model’. More recently Kolfin (2008:78) made a similar statement: Abstract Having a genuine black model at one’s disposal must have been a great event In this article I examine the production of artistically speaking. ... at least two other tronies or head studies of people of African painters from Rubens’ circle made oil origin made by the Flemish artists Peter Paul sketches of this man which seem to have Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, Jan I Brueghel, been inspired by Rubens’ study heads: Jacob Jordaens and Gaspar de Crayer in an Jacob Jordaens ... around 1620 and attempt to uncover their use of Africans1 as Gaspar de Crayer ... in the mid-1620s. models. In order to contextualise the research, Although Jordaens’ studies are definitely of the actual presence of Africans in Flanders the same man, this is harder to ascertain in the case of De Crayer’s work. is investigated. Although no documentation exists to calculate even an approximate Adding to this point of view, Massing (2011:1) number of Africans living in Flanders at that states that Rubens painted the same person time, travel accounts of foreigners visiting four times in the Brussels painting, ‘suggesting the commercial city of Antwerp testify that people of African origin were still rare in to its cosmopolitan character. -

The Rubenianum Quarterly

2016 The Rubenianum Quarterly 1 Announcing project Collection Ludwig Burchard II Dear friends, colleagues and benefactors, We are pleased to announce that through a generous donation the Rubenianum will be I have the pleasure to inform you of the able to dedicate another project to Ludwig Burchard’s scholarly legacy. The project entails imminent publication of the first part of two main components, both building on previous undertakings that have been carried the mythology volumes in the Corpus out to preserve the Rubenianum’s core collection and at the same time ensure enhanced Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard. The accessibility to the scholarly community of the wealth of Rubens documentation. Digitizing the Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard, launched in 2013 and successfully two volumes are going to press as we extended until May 2016, will be continued for all Corpus volumes published before 2003, speak and will be truly impressive. abiding by the moving wall of 15 years, that was agreed upon with Brepols Publishers, for the Consisting of nearly 1000 pages and over years 2016–18. 400 images, they will be a monumental The second and larger component of the project builds on the enterprise titled A treasure addition to our ever-growing catalogue trove of study material. Disclosure and valorization of the Collection Ludwig Burchard, raisonné of Rubens’s oeuvre and constitute successfully executed in 2014–15. An archival description of Rubenianum objects originating from Burchard’s library and documentation has since allowed for a virtual reconstruction a wonderful Easter present. of the expert’s scholarly legacy. Much emphasis was placed on the Rubens files during In the meantime, volume xix, 4 on Peter this project, while the collection contains many other resources that are of considerable Paul Rubens’s many portrait copies, importance to Rubens research. -

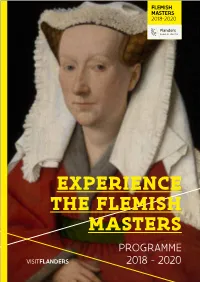

Experience the Flemish Masters Programme 2018 - 2020

EXPERIENCE THE FLEMISH MASTERS PROGRAMME 2018 - 2020 1 The contents of this brochure may be subject to change. For up-to-date information: check www.visitflanders.com/flemishmasters. 2 THE FLEMISH MASTERS 2018-2020 AT THE PINNACLE OF ARTISTIC INVENTION FROM THE MIDDLE AGES ONWARDS, FLANDERS WAS THE INSPIRATION BEHIND THE FAMOUS ART MOVEMENTS OF THE TIME: PRIMITIVE, RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE. FOR A PERIOD OF SOME 250 YEARS, IT WAS THE PLACE TO MEET AND EXPERIENCE SOME OF THE MOST ADMIRED ARTISTS IN WESTERN EUROPE. THREE PRACTITIONERS IN PARTICULAR, VAN EYCK, BRUEGEL AND RUBENS ROSE TO PROMINENCE DURING THIS TIME AND CEMENTED THEIR PLACE IN THE PANTHEON OF ALL-TIME GREATEST MASTERS. 3 FLANDERS WAS THEN A MELTING POT OF ART AND CREATIVITY, SCIENCE AND INVENTION, AND STILL TODAY IS A REGION THAT BUSTLES WITH VITALITY AND INNOVATION. The “Flemish Masters” project has THE FLEMISH MASTERS been established for the inquisitive PROJECT 2018-2020 traveller who enjoys learning about others as much as about him or The Flemish Masters project focuses Significant infrastructure herself. It is intended for those on the life and legacies of van Eyck, investments in tourism and culture who, like the Flemish Masters in Bruegel and Rubens active during are being made throughout their time, are looking to immerse th th th the 15 , 16 and 17 centuries, as well Flanders in order to deliver an themselves in new cultures and new as many other notable artists of the optimal visitor experience. In insights. time. addition, a programme of high- quality events and exhibitions From 2018 through to 2020, Many of the works by these original with international appeal will be VISITFLANDERS is hosting an Flemish Masters can be admired all organised throughout 2018, 2019 abundance of activities and events over the world but there is no doubt and 2020. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Saint Sebastian

SAINT SEBASTIAN In his semi-autobiographical novel Confessions of a Mask, the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima described his sexual awakening as a young boy when he came upon a reproduction of the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, a painting by the late Renaissance artist Guido Reni. The event is transferred to the fictional narrator, but recalled the actual event that had proved so formative for Mishima. A remarkably handsome youth was bound naked to the trunk of a tree. His crossed hands were raised high, and the thongs binding his wrists were tied to the tree. No other bonds were visible, and the only covering for the youth's nakedness was a coarse white cloth knotted loosely about his loins... Were it not for the arrows with their shafts deeply sunk into his left armpit and right side, he would seem more a Roman athlete resting from fatigue... The arrows have eaten into the tense, fragrant, youthful flesh, and are about to consume his body from within with flames of supreme agony and ecstasy.' The boy's hands embarked on a motion of which he had no experience; he played with his 'toy': "Suddenly it burst forth, bringing with it a blinding intoxication... Some time passed, and then, with miserable feelings I looked around the desk I was facing... There were cloud-splashes about... Some objects were dripping lazily, leadenly, and others gleamed dully, like the eyes of a dead fish. Fortunately, a reflex motion of my hand to protect the picture had saved the book from being soiled. The martyrdom of Saint Sebastian would prove to be a pivotal theme in Mishima’s life and art to which he would return time and time again. -

Who Was Protagoras? • Born in Abdêra, an Ionian Pólis in Thrace

Recovering the wisdom of Protagoras from a reinterpretation of the Prometheia trilogy Prometheus (c.1933) by Paul Manship (1885-1966) By: Marty Sulek, Ph.D. Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy For: Workshop In Multidisciplinary Philanthropic Studies February 10, 2015 Composed for inclusion in a Festschrift in honour of Dr. Laurence Lampert, a Canadian philosopher and leading scholar in the field of Nietzsche studies, and a professor emeritus of Philosophy at IUPUI. Adult Content Warning • Nudity • Sex • Violence • And other inappropriate Prometheus Chained by Vulcan (1623) themes… by Dirck van Baburen (1595-1624) Nietzsche on Protagoras & the Sophists “The Greek culture of the Sophists had developed out of all the Greek instincts; it belongs to the culture of the Periclean age as necessarily as Plato does not: it has its predecessors in Heraclitus, in Democritus, in the scientific types of the old philosophy; it finds expression in, e.g., the high culture of Thucydides. And – it has ultimately shown itself to be right: every advance in epistemological and moral knowledge has reinstated the Sophists – Our contemporary way of thinking is to a great extent Heraclitean, Democritean, and Protagorean: it suffices to say it is Protagorean, because Protagoras represented a synthesis of Heraclitus and Democritus.” Nietzsche, The Will to Power, 2.428 Reappraisals of the authorship & dating of the Prometheia trilogy • Traditionally thought to have been composed by Aeschylus (c.525-c.456 BCE). • More recent scholarship has demonstrated the play to have been written by a later, lesser author sometime in the 430s. • This new dating raises many questions as to what contemporary events the trilogy may be referring. -

Illustrated and Descriptive Catalogue and Price List of Stereopticons

—. ; I, £3,v; and Descriptive , Illustrated ;w j CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST- t&fs — r~* yv4 • .'../-.it *.•:.< : .. 4^. ; • ’• • • wjv* r,.^ N •’«* - . of . - VJ r .. « 7 **: „ S ; \ 1 ’ ; «•»'•: V. .c; ^ . \sK? *• .* Stereopticons . * ' «». .. • ” J- r . .. itzsg' Lantern Slides 1 -f ~ Accessories for Projection Stereopticon and Film Exchange W. B. MOORE, Manager. j. :rnu J ; 104 to no Franlclin Street ‘ Washington . (Cor. CHICAGO INDEX TO LANTERNS, ETC. FOR INDEX TO SLIDES SEE INDEX AT CLOSE OF CATALOGUE. Page Acetylene Dissolver 28 Champion Lantern 3g to 42 “ Gas 60 Check Valve S3 •* 1 • .• Gas Burner.... ; 19 Chemicals, Oxygen 74, 81 ** < .' I j Gas Generator.. ; 61 to 66 Chirograph 136 “ Gas Generator, Perfection to 66 64 Chlorate of Potash, tee Oxygen Chemicals 74 Adapter from to sire lenses, see Chromatrope.... 164 Miscellaneous....... 174 Cloak, How Made 151 Advertising Slides, Blank, see Miscellaneous.. 174 ** Slides 38010,387 " Slides 144 Color Slides or Tinters .^140 “ Slides, Ink for Writing, see Colored Films 297 Miscellaneous, 174 Coloring Films 134 “ Posters * *...153 " Slides Alcohol Vapor Mantle Light 20A v 147 Combined Check or Safety Valve 83 Alternating.Carbons, Special... 139 Comic and Mysterious Films 155 Allen Universal Focusing Lens 124, 125 Comparison of Portable Gas Outfits 93, 94 America, Wonders cf Description, 148 “Condensing Lens 128 Amet's Oro-Carbi Light 86 to 92, 94 " Lens Mounting 128 •Ancient Costumes ....! 131 Connections, Electric Lamp and Rheostat... 96, 97 Approximate Length of Focus 123 " Electric Stage 139 Arc Lamp 13 to 16 Costumes 130 to 152, 380 to 3S7 ** Lamp and Rheostat, How to Connect 96 Cover Glasses, see Miscellaneous ,....174 Arnold's Improved Calcium Light Outfit. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

Cultura, Vol. 21 | 2005 Poder De Convencimento E Narração Imagética Na Pintura Portuguesa Da Contra-R

Cultura Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias vol. 21 | 2005 Livro e Iconografia Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-reforma A influência de um gravado segundo Seghers numa tela do Convento dos Paulistas de Portel The power of persuasion and images narrative in counter-reformation Portuguese painting: the influente of an engraving following Seghers in a canvas of the Paulistas Monastery at Portel Vítor Serrão Edição electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cultura/2951 DOI: 10.4000/cultura.2951 ISSN: 2183-2021 Editora Centro de História da Cultura Edição impressa Data de publição: 1 Janeiro 2005 Paginação: 65-76 ISSN: 0870-4546 Refêrencia eletrónica Vítor Serrão, « Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra- reforma », Cultura [Online], vol. 21 | 2005, posto online no dia 26 maio 2016, consultado a 21 abril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cultura/2951 ; DOI : 10.4000/cultura.2951 Este documento foi criado de forma automática no dia 21 Abril 2019. © CHAM — Centro de Humanidades / Centre for the Humanities Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-r... 1 Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-reforma A influência de um gravado segundo Seghers numa tela do Convento dos Paulistas de Portel The power of persuasion and images narrative in counter-reformation Portuguese painting: the influente of an engraving following Seghers in a canvas of the Paulistas Monastery at Portel Vítor Serrão 1. A História da Arte reconhece hoje o papel muito destacado que foi assumido pela imagem gravada nos sucessivos processos de evolução artística.