Enlarge Auction Lots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

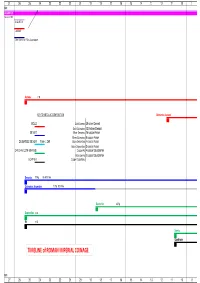

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Agorapicbk-15.Pdf

Excavations of the Athenian Agora Picture Book No. 1s Prepared by Fred S. Kleiner Photographs by Eugene Vanderpool, Jr. Produced by The Meriden Gravure Company, Meriden, Connecticut Cover design: Coins of Gela, L. Farsuleius Mensor, and Probus Title page: Athena on a coin of Roman Athens Greek and Roman Coins in the Athenian Agora AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1975 1. The Agora in the 5th century B.C. HAMMER - PUNCH ~ u= REVERSE DIE FLAN - - OBVERSE - DIE ANVIL - 2. Ancient method of minting coins. Designs were cut into two dies and hammered into a flan to produce a coin. THEATHENIAN AGORA has been more or less continuously inhabited from prehistoric times until the present day. During the American excava- tions over 75,000 coins have been found, dating from the 6th century B.c., when coins were first used in Attica, to the 20th century after Christ. These coins provide a record of the kind of money used in the Athenian market place throughout the ages. Much of this money is Athenian, but the far-flung commercial and political contacts of Athens brought all kinds of foreign currency into the area. Other Greek cities as well as the Romans, Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Turks have left their coins behind for the modern excavators to discover. Most of the coins found in the excavations were lost and never recovered-stamped into the earth floor of the Agora, or dropped in wells, drains, or cisterns. Consequently, almost all the Agora coins are small change bronze or copper pieces. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

234 the FINDS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona

234 SUFFOLK INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY THE FINDS THE COINS Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-161. Sestertius. Rev. Anona. B.M.C. 1654. From mediaeval pit. Julia Domna (wife of Septimius Severus), A.D. 193-211. Denarius. Rev. Juno. R.I.C. 560, B.M.C. 42. From primary silt of Ditch A south section. SeverusAlexander, A.D. 222-235. As. Rev. Sol. R.I.C. 543, B.M.C. 961. From fill of Ditch A west section at depth of one foot seveninches. Gallienus, A.D. 253-268. Antoninianus. Rev. Laetitia Aug. R.I.C. 226. From mediaevalpit. Claudius II, A.D. 268-270. Antoninianus. Rev. Fides Exerci. R.I.C. 36. From mediaeval pit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev.Virtus Aug. R.I.C. 145. From mediaevalpit. Tetricus I, A.D. 270-273. Antoninianus. Rev. uncertain. From west stoke-hole. 33.—Fragment of stone roofing tile (i). STONE (Fig. 33) By F. W. ANDERSON, D.SC., F.R.S.E. Fragment of stone roofing tile. This has split off parallel to the bedding: only half the depth of the hole is left, assumingthat, as is usual, the hole was bored from both sides. The rock appears to be a limestoneofLowerCarboniferousage. It isthus a foreigner to the area. It was probably made from a glacial erratic boulder in the drift, or else was imported from north England, south Scotland or possiblyBelgium, but it is impossibleto say which is the right answer. One can, however,say that the stone is not that normally usedby the Romans—i.e.it is not Purbeckor Collyweston A ROMANO-BRITISH BATH-HOUSE 235 or Stansfield Slate, nor any of the sandy flagstones used in the West Country.1° 34.—Lead drain pipe (i). -

Presidential Address 2014 Coin Hoards and Hoarding in Britain

PRESIDENTIAL ADDRESS 2014 COIN HOARDS AND HOARDING IN BRITAIN (3): RADIATE HOARDS ROGER BLAND Introduction IN my first presidential address I gave an overview of hoarding in Britain from the Bronze Age through to recent times,1 while last year I spoke about hoards from the end of Roman Britain.2 This arises from a research project (‘Crisis or continuity? Hoards and hoarding in Iron Age and Roman Britain’) funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and based at the British Museum and the University of Leicester. The project now includes the whole of the Iron Age and Roman periods from around 120 BC to the early fifth century. For the Iron Age we have relied on de Jersey’s corpus of 340 Iron Age coin hoards and we are grateful to him for giving us access to his data in advance of publica- tion.3 For the Roman period, our starting point has been Anne Robertson’s Inventory of Romano-British Coin Hoards (RBCH),4 which includes details of 2,007 hoards, including dis- coveries made down to about 1990. To that Eleanor Ghey has added new discoveries and also trawled other data sources such as Guest and Wells’s corpus of Roman coin finds from Wales,5 David Shotter’s catalogues of Roman coin finds from the North West,6 Penhallurick’s corpus of Cornish coin finds,7 Historic Environment Records and the National Monuments Record. She has added a further 1,045 Roman hoards, taking the total to 3,052, but this is not the final total. -

Costs of Living in Roman Palestine Iii by Daniel

COSTS OF LIVING IN ROMAN PALESTINE III BY DANIEL SPERBER THIRD CENTURY PRICE-LEVELS Continued *) Glancing back over our price-lists, it will be seen that while I and II cent. prices are relatively simple to analyse and compare with one another, (thanks to the general economic stability of the period), the material for the III and IV cent. presents a considerably different pic- ture. For this was a phase of monetary deterioration and economic flux. Thus, even a dated III cent. price given in denarii is of little use until we determine how much silver was in a denarius of that date. And even then one cannot easily compare the resultant price (now in terms of pure silver) with those of a former century. For the value of the denarius does not seem to have declined in an exact ratio to its diminu- tion in silver content. Rather it would appear, in an attempt to stem its rapid fall in value, silver was somewhat overvalued in relationship to gold; in other words, there appears to have been a shifting silver-gold ratio throughout the period.') Only when all these factors have been taken in account, can one attempt to compare III and IV cent. prices to those of the preceding centuries. Elsewhere 2) I have examined the problems of III and early IV cent. currency developments and metrological terminology in considerable detail. Here I shall do no more than give a brief summary of some of my findings. *) See vol. IX, pp. I82-2II 1) For the problems of gold and silver "standards" during this time, and the con- temporary Rabbinic appreciation of these economic concepts, see my forthcoming article in Numismatic Chronicle 196 8, entitled "Rabbinic attitudes to Roman currency". -

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6

Ancient Roman Measures Page 1 of 6 Ancient Rome Table of Measures of Length/Distance Name of Unit (Greek) Digitus Meters 01-Digitus (Daktylos) 1 0.0185 02-Uncia - Polex 1.33 0.0246 03-Duorum Digitorum (Condylos) 2 0.037 04-Palmus (Pala(i)ste) 4 0.074 05-Pes Dimidius (Dihas) 8 0.148 06-Palma Porrecta (Orthodoron) 11 0.2035 07-Palmus Major (Spithame) 12 0.222 08-Pes (Pous) 16 0.296 09-Pugnus (Pygme) 18 0.333 10-Palmipes (Pygon) 20 0.370 11-Cubitus - Ulna (pechus) 24 0.444 12-Gradus – Pes Sestertius (bema aploun) 40 0.74 13-Passus (bema diploun) 80 1.48 14-Ulna Extenda (Orguia) 96 1.776 15-Acnua -Dekempeda - Pertica (Akaina) 160 2.96 16-Actus 1920 35.52 17-Actus Stadium 10000 185 18-Stadium (Stadion Attic) 10000 185 19-Milliarium - Mille passuum 80000 1480 20-Leuka - Leuga 120000 2220 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 2 of 6 Table of Measures of Area Name of Unit Pes Quadratus Meters2 01-Pes Quadratus 1 0.0876 02-Dimidium scrupulum 50 4.38 03-Scripulum - scrupulum 100 8.76 04-Actus minimus 480 42.048 05-Uncia 2400 210.24 06-Clima 3600 315.36 07-Sextans 4800 420.48 08-Actus quadratus 14400 1261.44 09-Arvum - Arura 22500 1971 10-Jugerum 28800 2522.88 11-Heredium 57600 5045.76 12-Centuria 5760000 504576 13-Saltus 23040000 2018304 http://www.anistor.gr/history/diophant.html Ancient Roman Measures Page 3 of 6 Table of Measures of Liquids Name of Unit Ligula Liters 01-Ligula 1 0.0114 02-Uncia (metric) 2 0.0228 03-Cyathus 4 0.0456 04-Acetabulum 6 0.0684 05-Sextans 8 0.0912 06-Quartarius – Quadrans 12 0.1368 -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

3927 25.90 Brass 6 Obols / Sestertius 3928 24.91

91 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS 3927 25.90 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3928 24.91 brass 6 obols / sestertius 3929 14.15 brass 3 obols / dupondius 3930 16.23 brass same (2 examples weighed) 3931 6.72 obol / 2/3 as (3 examples weighed) 3932 9.78 3/2 obol / as *Not struck at a Cypriot mint. 92 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Cypriot Coinage under Tiberius and Later, After 14 AD To the people of Cyprus, far from the frontiers of the Empire, the centuries of the Pax Romana formed an uneventful although contented period. Mattingly notes, “Cyprus . lay just outside of the main currents of life.” A population unused to political independence or democratic institutions did not find Roman rule oppressive. Radiate Divus Augustus and laureate Tiberius on c. 15.6g Cypriot dupondius - triobol. In c. 15-16 AD the laureate head of Tiberius was paired with Livia seated right (RPC 3919, as) and paired with that of Divus Augustus (RPC 3917 and 3918 dupondii). Both types are copied from Roman Imperial types of the early reign of Tiberius. For his son Drusus, hemiobols were struck with the reverse designs begun by late in the reign of Cleopatra: Zeus Salaminios and the Temple of Aphrodite at Paphos. In addition, a reverse with both of these symbols was struck. Drusus obverse was paired with either Zeus Salaminios, or Temple of Aphrodite reverses, as well as this reverse that shows both. (4.19g) Conical black stone found in 1888 near the ruins of the temple of Aphrodite at Paphos, now in the Museum of Kouklia. -

GREEK and ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek

GREEK AND ROMAN COINS GREEK COINS Technique Ancient Greek coins were struck from blank pieces of metal first prepared by heating and casting in molds of suitable size. At the same time, the weight was adjusted. Next, the blanks were stamped with devices which had been prepared on the dies. The lower die, for the obverse, was fixed in the anvil; the reverse was attached to a punch. The metal blank, heated to soften it, was placed on the anvil and struck with the punch, thus producing a design on both sides of the blank. Weights and Values The values of Greek coins were strictly related to the weights of the coins, since the coins were struck in intrinsically valuable metals. All Greek coins were issued according to the particular weight system adopted by the issuing city-state. Each system was based on the weight of the principal coin; the weights of all other coins of that system were multiples or sub-divisions of this major denomination. There were a number of weight standards in use in the Greek world, but the basic unit of weight was the drachm (handful) which was divided into six obols (spits). The drachm, however, varied in weight. At Aigina it weighed over six grammes, at Corinth less than three. In the 6th century B.C. many cities used the standard of the island of Aegina. In the 5th century, however, the Attic standard, based on the Athenian tetradrachm of 17 grammes, prevailed in many areas of Greece, and this was the system adopted in the 4th century by Alexander the Great. -

Debasement and the Decline of Rome Kevin Butcher1

Debasement and the decline of Rome KEVIN BUTCHER1 On April 23, 1919, the London Daily Chronicle carried an article that claimed to contain notes of an interview with Lenin, conveyed by an anonymous visitor to Moscow.2 This explained how ‘the high priest of Bolshevism’ had a plan ‘for the annihilation of the power of money in this world.’ The plan was presented in a collection of quotations allegedly from Lenin’s own mouth: “Hundreds of thousands of rouble notes are being issued daily by our treasury. This is done, not in order to fill the coffers of the State with practically worthless paper, but with the deliberate intention of destroying the value of money as a means of payment … The simplest way to exterminate the very spirit of capitalism is therefore to flood the country with notes of a high face-value without financial guarantees of any sort. Already the hundred-rouble note is almost valueless in Russia. Soon even the simplest peasant will realise that it is only a scrap of paper … and the great illusion of the value and power of money, on which the capitalist state is based, will have been destroyed. This is the real reason why our presses are printing rouble bills day and night, without rest.” Whether Lenin really uttered these words is uncertain.3 What seems certain, however, is that the real reason the Russian presses were printing money was not to destroy the very concept of money. It was to finance their war against their political opponents. The reality was that the Bolsheviks had carelessly created the conditions for hyperinflation. -

Roman Imperatorial and Imperial Coinage Bernhard E

Roman Imperatorial and Imperial Coinage Bernhard E. Woytek The Periods • Civil Wars at the End of the Republic (49 – 31 BC) Issues of the Rome Mint – “Imperatorial“ Issues • Principate (31/27 BC – AD 284: Diocletian) “Augustan“ System (with modifications: Caracalla etc.) Imperial Coinage and Provincial Coinages • Dominate (AD 284 – 491: Anastasius I.) Unified Currency. Monetary Reforms of Diocletian, Constantine I. and of Constantine‘s Sons The Roman „Imperial“ Coinage: Three Important Aspects • Creation of a Regular Gold Coinage: Aureus (produced continuously from Caesar onwards), Solidus (created under Constantine I.) • Portrait of the Ruler on the Obverse: Introduced to Rome under Caesar, 44 BC • Creation of the Medallion: Coin-like, non-monetary object, outside the denominational system, but produced by the official mint Gold Coinage Aureus, Julius Caesar, 48 BC Less than 10 pieces known Gold Coinage First Large Issue of Aurei produced under Caesar‘s Rule: Aulus Hirtius, Praetor, 46 BC Die Study (RIN 2003, M. C. Molinari): 537 pieces listed Gold Coinage: Augustus (27 BC – AD 14) 1 Aureus = 25 Denarii (see Cassius Dio 55,12,3) Imperial Bronze Coinage: The Augustan System 1 Denarius = 4 Sestertii From Augustus on in BRASS: Part of the coinage reform, made Senatus Consulto (SC) 1 Sestertius = 2 Dupondii 1 Dupondius = 2 Asses Gold Coinage: Nero (AD 54-68) Nero‘s Monetary Reform (AD 64): Aurei struck on a Standard of 45 to the Roman pound (libra: c. 327g) -> theoretically c. 7.27g (but struck al marco) Gold Coinage: Caracalla (AD 211-217) Introduction of the Double Aureus (Binio) (British Museum, Inv. 1867,0101.772: 13.02g) Gold Coinage: Gallienus (AD 253-268) Aureus, Rome, 264-267 6.07g Aureus, Rome, 257 2.36g „Binio“, Mediolanum, 262 3.64g Weights vary considerably -> coin values had to be established individually Fineness of Imperial Gold Coins Source: C.