Parliamentary Inquiry Into Biodiversity Loss And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2016 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Jill Barnard Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) Marie Clark Mimi Colligan Don Garden (President, RHSV) Don Gibb David Harris (Editor, Victorian Historical Journal) Kate Prinsley Marian Quartly (Editor, History News) John Rickard Judith Smart (Review Editor) Chips Sowerwine Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 286 VOLUME 87, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2016 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2016 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

Annual Report 2020 Five Years of Growth 2 WESTERN VICTORIA PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK

Annual Report 2020 Five years of growth 2 WESTERN VICTORIA PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK Contents About this Report . 3 Who We Are . 4 Report from the Chair . 6 Report from the Chief Executive Officer . 7 Financial Summary . .. 8 Strategic Plan 2017-2020 . 10 COVID-19 Changing the way we work . 14 Our Board . 16 Our Executive . 17 Organisation Chart . 17 Clinical and Community Advisory Councils . 18 3 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 About this report The Western Victoria Primary Health Network (WVPHN) Annual Report 2020 provides an overview of our activities and performance from July 1, 2019 to June 30, 2020. This report provides details on our services, how we have performed and information on the people who have worked with us and for us. This report was presented at the WVPHN Annual General Meeting on 29 October 2020. Theme of this report We welcome your feedback WVPHN has been operating for five Feedback is important to us and years – established 1 July 2015 . contributes to improving future reports for our readers . We welcome The design of this report depicts five your comments about this annual stylised growth lines, similar to growth report and ask you to forward them to rings in a tree . communications@westvicphn .com .au It also represents the organisation as The Annual Report 2020 is available being part of the health care landscape, online and can be downloaded: deeply integrated in the region and https://www westvicphn. .com .au/about- continuing to grow . us/publications/annual-reports 4 WESTERN VICTORIA PRIMARY HEALTH NETWORK Who We Are Western Victoria WVPHN is one of 31 Primary Health Networks (PHNs) across Australia and one of six in Victoria. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

Great Ocean Road and Scenic Environs National Heritage List

Australian Heritage Database Places for Decision Class : Historic Item: 1 Identification List: National Heritage List Name of Place: Great Ocean Road and Rural Environs Other Names: Place ID: 105875 File No: 2/01/140/0020 Primary Nominator: 2211 Geelong Environment Council Inc. Nomination Date: 11/09/2005 Principal Group: Monuments and Memorials Status Legal Status: 14/09/2005 - Nominated place Admin Status: 22/08/2007 - Included in FPAL - under assessment by AHC Assessment Recommendation: Place meets one or more NHL criteria Assessor's Comments: Other Assessments: : Location Nearest Town: Apollo Bay Distance from town (km): Direction from town: Area (ha): 42000 Address: Great Ocean Rd, Apollo Bay, VIC, 3221 LGA: Surf Coast Shire VIC Colac - Otway Shire VIC Corangamite Shire VIC Location/Boundaries: About 10,040ha, between Torquay and Allansford, comprising the following: 1. The Great Ocean Road extending from its intersection with the Princes Highway in the west to its intersection with Spring Creek at Torquay. The area comprises all that part of Great Ocean Road classified as Road Zone Category 1. 2. Bells Boulevarde from its intersection with Great Ocean Road in the north to its intersection with Bones Road in the south, then easterly via Bones Road to its intersection with Bells Beach Road. The area comprises the whole of the road reserves. 3. Bells Beach Surfing Recreation Reserve, comprising the whole of the area entered in the Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) No H2032. 4. Jarosite Road from its intersection with Great Ocean Road in the west to its intersection with Bells Beach Road in the east. -

Aboriginal Reconciliation Action Plan 2017–19 Summary

Aboriginal Reconciliation Action Plan 2017–19 Summary Cover art: Jarra Karalinar Steel, Boon Wurrung Alfred Health uses the term ‘Aboriginal’ to mean both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander throughout this document Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are warned that this document may contain images and names of deceased people. Message from our Chief Executive I am delighted to present Alfred Health’s first Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP): a living and practical plan built around strong relationships, respect and pride in our local Aboriginal community and the potential for employment and business opportunities. This plan is something of a watershed in our relationship with our Aboriginal community. It recognises that we need to do better in providing care for our Aboriginal patients and commits us to a journey to achieve greater equality in healthcare for our first peoples. Already it has been a two-year journey in developing this plan and along the way we have learnt much about what reconciliation means to us and the importance of meaningful and respectful relationships. Thanks must go to the many people involved in creating this plan, particularly to local elder Caroline Briggs, The Boon Wurrung Foundation, and Reconciliation Australia who have supported and guided us through this process. More about our plan The vision for reconciliation is for all Australians to be equal, to have equal opportunities and for there to be trust as we move forward in a shared vision for our country. I sincerely hope that this plan This plan is a summary of and the energy and commitment of our Alfred Health staff will contribute to achieving this vision. -

Engaging Indigenous Communities

Engaging Indigenous Communities REGIONAL INDIGENOUS FACILITATOR INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S GOALS AND The Port Phillip & Westernport CMA employs a Regional ASPIRATIONS Indigenous Facilitator funded through the Australian During 2014/15, a study was undertaken with Government’s National Landcare Programme. In Wurundjeri, Wathaurung, Wathaurong and Boon 2014/15, the facilitator arranged numerous events Wurrung people regarding their communities’ goals and and activities to improve the Indigenous cultural aspirations for involvement in land management and awareness and understanding of Board members and sustainable agriculture. The study improved the mutual staff from the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and from understanding of priority activities for the future and various other organisations and community groups. set a basis for potential formal agreements between The facilitator also worked directly with Indigenous the Port Phillip & Westernport CMA and the Indigenous organisations and communities to document their goals organisations. relating to natural resource management and agriculture. A coordinated program of grants was established to help INDIGENOUS ENVIRONMENT GRANTS Indigenous organisations undertake on-ground projects and training to increase employment opportunities. In 2014/15, $75,000 of Indigenous environment grants were awarded as part of the Port Phillip & Westernport IMPROVING CULTURAL AWARENESS AND CMA’s project. This included grants to: UNDERSTANDING • Wathaurung Aboriginal Corporation to run 4 community, business and corporate -

Your Candidates Metropolitan

YOUR CANDIDATES METROPOLITAN First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria Election 2019 “TREATY TO ME IS A RECOGNITION THAT WE ARE THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF THIS COUNTRY AND THAT OUR VOICE BE HEARD AND RESPECTED” Uncle Archie Roach VOTING IS OPEN FROM 16 SEPTEMBER – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Treaties are our self-determining right. They can give us justice for the past and hope for the future. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be our voice as we work towards Treaties. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be set up this year, with its first meeting set to be held in December. The Assembly will be a powerful, independent and culturally strong organisation made up of 32 Victorian Traditional Owners. If you’re a Victorian Traditional Owner or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person living in Victoria, you’re eligible to vote for your Assembly representatives through a historic election process. Your voice matters, your vote is crucial. HAVE YOU ENROLLED TO VOTE? To be able to vote, you’ll need to make sure you’re enrolled. This will only take you a few minutes. You can do this at the same time as voting, or before you vote. The Assembly election is completely Aboriginal owned and independent from any Government election (this includes the Victorian Electoral Commission and the Australian Electoral Commission). This means, even if you vote every year in other elections, you’ll still need to sign up to vote for your Assembly representatives. Don’t worry, your details will never be shared with Government, or any electoral commissions and you won’t get fined if you decide not to vote. -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Gilbert, Stephanie; Richards, Jonathan; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Usher, Kaine, 2019. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources 0 Abbreviations 1 Unpublished Archival Sources 2 Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia 2 State Records of NSW (SRNSW) 2 Mitchell Library - State Library of New South Wales (MLSLNSW) 3 National Library of Australia (NLA) 3 Northern Territory Archives Service (NTAS) 4 Oxley Memorial Library, State Library Of Queensland 4 National Archives, London (PRO) 4 Queensland State Archives (QSA) 4 State Libary Of Victoria (SLV) - La Trobe Library, Melbourne 5 State Records Of Western Australia (SROWA) 5 Tasmanian Archives And Heritage Office (TAHO), Hobart 7 Colonial Secretary’s Office (CSO) 1/321, 16 June, 1829; 1/316, 24 August, 1831. 7 Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS), Melbourne 7 Manuscripts, Theses and Typescripts 8 Newspapers 9 Films and Artworks 12 Printed and Electronic Sources 13 Colonial Frontier Massacres In Australia, 1788-1930: Sources 1 Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project ANU Australian National University AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania -

Corangamite Heritage Study Stage 2 Volume 3 Reviewed

CORANGAMITE HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 2 VOLUME 3 REVIEWED AND REVISED THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Prepared for Corangamite Shire Council Samantha Westbrooke Ray Tonkin 13 Richards Street 179 Spensley St Coburg 3058 Clifton Hill 3068 ph 03 9354 3451 ph 03 9029 3687 mob 0417 537 413 mob 0408 313 721 [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION This report comprises Volume 3 of the Corangamite Heritage Study (Stage 2) 2013 (the Study). The purpose of the Study is to complete the identification, assessment and documentation of places of post-contact cultural significance within Corangamite Shire, excluding the town of Camperdown (the study area) and to make recommendations for their future conservation. This volume contains the Reviewed and Revised Thematic Environmental History. It should be read in conjunction with Volumes 1 & 2 of the Study, which contain the following: • Volume 1. Overview, Methodology & Recommendations • Volume 2. Citations for Precincts, Individual Places and Cultural Landscapes This document was reviewed and revised by Ray Tonkin and Samantha Westbrooke in July 2013 as part of the completion of the Corangamite Heritage Study, Stage 2. This was a task required by the brief for the Stage 2 study and was designed to ensure that the findings of the Stage 2 study were incorporated into the final version of the Thematic Environmental History. The revision largely amounts to the addition of material to supplement certain themes and the addition of further examples of places that illustrate those themes. There has also been a significant re-formatting of the document. Most of the original version was presented in a landscape format. -

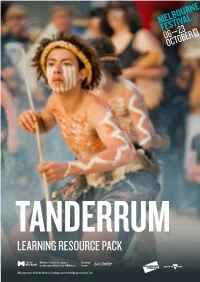

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Racist Structures and Ideologies Regarding Aboriginal People in Contemporary and Historical Australian Society

Master Thesis In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science: Development and Rural Innovation Racist structures and ideologies regarding Aboriginal people in contemporary and historical Australian society Robin Anne Gravemaker Student number: 951226276130 June 2020 Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Course code: SDC-80436 Wageningen University & Research i Abstract Severe inequalities remain in Australian society between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This research has examined the role of race and racism in historical Victoria and in the contemporary Australian government, using a structuralist, constructivist framework. It was found that historical approaches to governing Aboriginal people were paternalistic and assimilationist. Institutions like the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, which terrorised Aboriginal people for over a century, were creating a racist structure fuelled by racist ideologies. Despite continuous activism by Aboriginal people, it took until 1967 for them to get citizens’ rights. That year, Aboriginal affairs were shifted from state jurisdiction to national jurisdiction. Aboriginal people continue to be underrepresented in positions of power and still lack self-determination. The national government of Australia has reproduced historical inequalities since 1967, and racist structures and ideologies remain. ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Elisabet Rasch, for her support and constructive criticism. I thank my informants and other friends that I met in Melbourne for talking to me and expanding my mind. Floor, thank you for showing me around in Melbourne and for your never-ending encouragement since then, via phone, postcard or in person. Duane Hamacher helped me tremendously by encouraging me to change the topic of my research and by sharing his own experiences as a researcher.