Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A RESOLUTION to Honor and Commend David L. Solomon Upon Being Named to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Business and Industry Hall of Fame

Filed for intro on 03/11/2002 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 732 By Harwell A RESOLUTION to honor and commend David L. Solomon upon being named to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Business and Industry Hall of Fame. WHEREAS, it is fitting that the members of this General Assembly should salute those citizens who through their extraordinary efforts have distinguished themselves both in their chosen professions and as community leaders of whom we can all be proud; and WHEREAS, one such noteworthy person is David L. Solomon, Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and Director of NuVox Communications, who makes his home in Nashville, Tennessee; and WHEREAS, David Solomon embarked upon a career as an accountant when his father, Frazier Solomon, former Director of State Audit and Personnel Director of the Office of the Comptroller of the Treasury of the State of Tennessee, read bedtime stories to him from an accounting manual from the age of four; David grew up to be the husband of a CPA and the son-in-law of a CPA; and WHEREAS, Mr. Solomon earned a Bachelor of Science in accounting from David Lipscomb University in Nashville in 1981 and went to work for the public accounting firm of HJR0732 01251056 -1- KPMG Peat Marwick; during his thirteen years at KPMG Peat Marwick, he rose to the rank of partner, gaining experience in public and private capital markets, financial management and reporting; and WHEREAS, David Solomon left in 1994 to join Brooks Fiber Properties (BFP) as Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, as well as Chief Financial Officer, Secretary and Director of Brooks Telecommunications Corporation until it was acquired by BFP in January 1996; while at BFP, he was involved in all aspects of strategic development, raised over $1.6 billion in equity and debt, and built or acquired systems in 44 markets; and WHEREAS, since 1998, when BFP was sold to MCI WorldCom in a $3.4 billion transaction, Mr. -

Neo-Assyrian Palaces and the Creation of Courtly Culture

Journal of Ancient History 2019; 7(1): 1–31 Melanie Groß* and David Kertai Becoming Empire: Neo-Assyrian palaces and the creation of courtly culture https://doi.org/10.1515/jah-2018-0026 Abstract: Assyria (911–612 BCE) can be described as the founder of the imperial model of kingship in the ancient Near East. The Assyrian court itself, however, remains poorly understood. Scholarship has treated the court as a disembodied, textual entity, separated from the physical spaces it occupied – namely, the pa- laces. At the same time, architectural analyses have examined the physical struc- tures of the Assyrian palaces, without consideration for how these structures were connected to people’s lives and works. The palaces are often described as se- cluded, inaccessible locations. This study presents the first model of the Assyrian court contextualized in its actual palaces. It provides a nuanced model highlight- ing how the court organized the immense flow of information, people and goods entering the palace as a result of the empire’s increased size and complexity. It argues that access to the king was regulated by three gates of control which were manned by specific types of personnel and a more situational organization that moved within the physical spaces of the palace and was contingent on the king’s activity. Keywords: court culture, kingship, Assyrian Empire, royal palace As the first in a long sequence of empires to rule the Middle East, Assyria can be described as the founder of the imperial model of kingship. Its experiments in becoming an empire and the resulting courtly culture informed the empires that Anmerkung: This joined study has been supported by the Martin Buber Society of Fellows in the Humanities and Social Sciences at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. -

Divine Help: 1 Samuel 27

Training Divine Help | GOD PROTECTS AND VINDICATES DAVID AGAIN What Do I Need to Know About the Passage? What’s the Big Idea? 1 Samuel 27:1-31:13 David has a second chance to kill Saul, but he spares him. Again, we learn the wonderful As we close out 1 Samuel, we cover a wide swath of narrative in this final lesson. truth that God protects His people, delivers You do not need to read chapter 31 during the study, but it is important that your them, and vindicates them as they trust in students know what it says. This narrative focuses on one theme: God pursues His Him. This lesson should lead us to experi- people and rejects those who reject Him. ence hope and encouragement because of God’s ultimate protection and vindication David Lives with the Philistines (27:1-28:2) through His Son Jesus. Immediately after experiencing deliverance from the LORD, David doubts God’s protection of his life. In 27:1, David says, “Now I shall perish one day by the hand of Saul. There is nothing better for me than that I should escape to the land of the Philistines.” What a drastic change of heart and attitude! David turns to his flesh as he worries whether God will continue to watch over him. Certainly we have experienced this before, but God has a perfect track record of never letting His people down. Make sure the group understands that God’s promises are always just that – promises! He can’t break them. What’s the Problem? We are selfish, impatient people who want David goes to King Achish for help, but this time, David doesn’t present himself as a situations to work out the way we want crazy man (see 21:10). -

Why Did Nebuchadnezzar II Destroy Ashkelon in Kislev 604 ...?

Offprint From The Fire Signals of Lachish Studies in the Archaeology and History of Israel in the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Persian Period in Honor of David Ussishkin Edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Naʾaman Winona Lake, Indiana Eisenbrauns 2011 © 2011 by Eisenbrauns Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. www.eisenbrauns.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The fire signals of Lachish : studies in the archaeology and history of Israel in the late Bronze age, Iron age, and Persian period in honor of David Ussishkin / edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Naʾaman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-57506-205-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Israel—Antiquities. 2. Excavations (Archaeology)—Israel. 3. Bronze age— Israel. 4. Iron age—Israel. 5. Material culture—Palestine. 6. Palestine—Antiquities. 7. Ussishkin, David. I. Finkelstein, Israel. II. Naʾaman, Nadav. DS111.F57 2011 933—dc22 2010050366 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. †Ê Why Did Nebuchadnezzar II Destroy Ashkelon in Kislev 604 ...? Alexander Fantalkin Tel Aviv University Introduction The significance of the discovery of a destruction layer at Ashkelon, identified with the Babylonian assault in Kislev, 604 B.C.E, can hardly be overestimated. 1 Be- yond the obvious value of this find, which provides evidence for the policies of the Babylonian regime in the “Hatti-land,” it supplies a reliable chronological anchor for the typological sequencing and dating of groups of local and imported pottery (Stager 1996a; 1996b; Waldbaum and Magness 1997; Waldbaum 2002a; 2002b). -

Tribute to Simon Sargon Shabbat Noach November 5, 2016 Rabbi David Stern

Tribute to Simon Sargon Shabbat Noach November 5, 2016 Rabbi David Stern When Simon was born in 1938 in Mumbai, the truth is he wasn’t the first Sargon. Of course, his father was named Benjamin Sargon, but if you know something about the history of Mesopotamia, you know that scholars estimate that there have been Sargons around for about forty-five centuries. So I thought maybe we could learn something about Simon by looking at his antecedent Sargons. One of them is mentioned in the Bible, in the Book of Isaiah. He is known as Sargon II, an Assyrian King of the 8th century BCE who took power by violent coup, and then completed the defeat of the Kingdom of Israel. That did not seem like the most noble exemplar, so I decided to look further. About 1200 years before Sargon II, there was Sargon I, which is a pretty long time to go without a King Sargon. And to make matters worse, Sargon I did not leave much of a footprint. He shows up in ancient lists of Assyrian kings, but that’s about it. Undeterred, we search on. And that’s what brings us to an Akkadian king of the 24th century BCE known as Sargon the Great. Now we’re getting somewhere. Because Sargon the Great was just that – a successful warrior, a model and powerful ruler who was known for listening to his subordinates. He creates a dynasty, and creates a model of leadership for centuries of Mesopotamian kings to follow. But while Sargon the Great gets us closer to what our Sargon means to us, it’s really not close enough. -

Acra Fortress, Built by Antiochus As He Sought to Quell a Jewish Priestly Rebellion Centered on the Temple

1 2,000-year-old fortress unearthed in Jerusalem after century-long search By Times of Israel staff, November 3, 2015, 2:52 pm http://www.timesofisrael.com/maccabean-era-fortress-unearthed-in-jerusalem-after-century-long- search/ Acra fortification, built by Hanukkah villain Antiochus IV Epiphanes, maintained Seleucid Greek control over Temple until its conquest by Hasmoneans in 141 BCE In what archaeologists are describing as “a solution to one of the great archaeological riddles in the history of Jerusalem,” researchers with the Israel Antiquities Authority announced Tuesday that they have found the remnants of a fortress used by the Seleucid Greek king Antiochus Epiphanes in his siege of Jerusalem in 168 BCE. A section of fortification was discovered under the Givati parking lot in the City of David south of the Old City walls and the Temple Mount. The fortification is believed to have been part of a system of defenses known as the Acra fortress, built by Antiochus as he sought to quell a Jewish priestly rebellion centered on the Temple. 2 Antiochus is remembered in the Jewish tradition as the villain of the Hanukkah holiday who sought to ban Jewish religious rites, sparking the Maccabean revolt. The Acra fortress was used by his Seleucids to oversee the Temple and maintain control over Jerusalem. The fortress was manned by Hellenized Jews, who many scholars believe were then engaged in a full-fledged civil war with traditionalist Jews represented by the Maccabees. Mercenaries paid by Antiochus rounded out the force. Lead sling stones and bronze arrowheads stamped with the symbol of the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, evidence of the attempts to conquer the Acra citadel in Jerusalem’s City of David in Maccabean days. -

A Story of Return and Longing: the Life of King David Rabbi Adam Stock Spilker, Mount Zion Temple Kol Nidre 5773 – September 25, 2012

A Story of Return and Longing: The Life of King David Rabbi Adam Stock Spilker, Mount Zion Temple Kol Nidre 5773 – September 25, 2012 This is the story of David, King of Israel, in three acts. His story is complex and somehow real – a boy shepherd, a musician with healing powers, a poet laureate, a general, a king. His life may feel distant, yet his words, the psalms he wrote, still speak to us. To anyone who has ever sought forgiveness or yearned for anything or anyone, this is a story for you - a sermon in parable. Act 1 – David, a Shepard Healer In the book of Samuel, we meet young David. The prophet Samuel is told by God to anoint one of the sons of Jesse who lives in Bethlehem as the future king of Israel. This is all happening while Saul is still king. Trouble and intrigue start from the beginning of David’s life. As Samuel tries to figure out which of the sons of Jesse to anoint, God says: “Pay no attention to his appearance or his stature; …for I see not as man sees; for man looks only what is visible, but the Eternal looks into the heart.” (Sam 16:7). Soon after David is anointed, we are told that his heart actually is not the only thing people find attractive. One of the attendants in King Saul’s court says: “I have seen a son of Jesse … who is skilled in music; he is a stalwart fellow and a warrior, sensible in speech, and handsome in appearance and the Eternal is with him.” (Sam 16:18). -

Return of Rule of Christ Daniel 1-4 Old Testament Timeline Daniel Initial

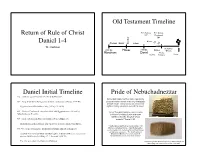

Old Testament Timeline First Temple First Temple Return of Rule of Christ 957 Destroyed 586 Kings Daniel 1-4 Exodus 722 Canaan Egypt Judges 586 W. Cochran Alexander 2000 BC Moses 1000 BC Babylon Greece Abraham David Medes Assyria Persians Rome Daniel Initial Timeline Pride of Nebuchadnezzar • 612 : Assyrian capital Nineveh overrun by Babylonians. Nebuchadnezzar had his name repeatedly • 609 : King Josiah killed by Egyptians in Battle of Megiddo (2 Kings 23:28-30). pressed into the bricks of the city of Babylon he had rebuilt, so his bricks are a common • Egyptians install Jehoiakim as king (2 Kings 23:34-36). sight in history museums around the world. • 605 : Battle of Carchemish : Assyrians allied with Egyptians were defeated by “Is not this great Babylon, which I have Nebuchadnezzar II’s army. built by my mighty power as a royal residence and for the glory of my • 597 : Siege of Jerusalem. First deportation of Jews (2 Kings 24) majesty?” Daniel 4:30 • Zedekiah installed as tributary king but revolts and joins alliance with Egypt. “I built a strong wall that cannot be shaken with 589-586 : Siege of Jerusalem. Destruction of temple and city (2 Kings 25) bitumen and baked bricks… I laid its foundation • on the breast of the netherworld, and I built its top as high as a mountain… The fortifications of • Zedekiah was blinded, bound, and taken captive to Babylon where he remained as Esagila and Babylon I strengthened and prisoner until his death (2 Kings 25:7; Jeremiah 52:10,11). established the name of my reign forever.” • The elite were taken into Captivity in Babylon Cuneiform cylinder with inscription of Nebuchadnezzar describing the construction of the outer wall. -

Queen Regency in the Seleucid Empire

Interregnum: Queen Regency in the Seleucid Empire by Stacy Reda A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Ancient Mediterranean Cultures Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2014 © Stacy Reda 2014 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract An examination of the ancient sources indicates that there were possibly seven Queens Regent throughout the course of the Seleucid Dynasty: Apama, Laodice I, Berenice Syra, Laodice III, Laodice IV, Cleopatra I Thea, and Cleopatra II Selene. This thesis examines the institution of Queen Regency in the Seleucid Dynasty, the power and duties held by the Queen Regent, and the relationship between the Queen and her son—the royal heir. This thesis concludes that Queen Regency was not a set office and that there were multiple reasons and functions that could define a queen as a regent. iii Acknowledgements I give my utmost thanks and appreciation to the University of Waterloo’s Department of Classical Studies. The support that I have received from all members of the faculty during my studies has made a great impact on my life for which I will always be grateful. Special thanks to my advisor, Dr. Sheila Ager, for mentoring me through this process, and Dr. Maria Liston (Anthropology) for her support and guidance. -

Daniel02.Pdf

1 2 1 The Genealogy of Noah 3 4 2 The Cradle of Civilization 5 Timeline - Mesopotamia 6 3 7 SUMER Shinar (in Hebrew) Sanhar (in Hittie) Sngr (in Egyptian) 8 4 1ST DYNASTY 2nd DYNASTY ca 3500 B.C. ca 2330 B.C. 3rd DYNASTY Cities develop in Sargon of ca 2350 B.C. ca 2100 B.C. ca 2100 B.C. Sumer, forming Akkad conquers Naram-Sin, Ur-Nammu of Ur, Babylon, a city- the basis for Sumer and goes Sargon’s takes command state in Akkad, Mesopotamian to expand his grandson, of Sumer and emerges as an Civilization. domain. takes power. Akkad. imperial power. AKKADIAN EMPIRE ca 2500 B.C. ca 2280 B.C. Royal burials at Sargon dies, ca 2220 B.C. ca 2000 B.C. the Sumerian city- bequeathing control Akkadian Empire Ur destroyed by state of Ur include of his empire to his collapses following the invading Elamites. death of Naram-Sin. human sacrifices. heirs. 4th DYNASTY 9 5th DYNASTY OLD BABYLON KASSITE BABYLON 1792 B.C. 1595 B.C. ca 900 B.C. NEO-BABYLONIAN EMPIRE Hammurabi Hittites Assyrians emerge 612 B.C. 539 B.C. becomes king of descend from as the dominant Babylonians Babylon falls to Babylon and the north and force in defeat Assyrians Cyrus the Great begins forging an conquer Mesopotamia and and inherit their of Persia. empire. Babylon. surrounding lands. empire. BABYLONIAN EMPIRE ca 1750 B.C. ca 1120 B.C. 689 B.C. 587 B.C. Hammurabi dies, Nebuchadnezzar I King Sennacherib of Jerusalem falls to the leaving his code of takes power and Assyria destroys Babylonian army of laws as his chief launches a brief Babylon, which is later Nebuchadnezzar II. -

Death in Sumerian Literary Texts

Death in Sumerian Literary Texts Establishing the Existence of a Literary Tradition on How to Describe Death in the Ur III and Old Babylonian Periods Lisa van Oudheusden s1367250 Research Master Thesis Classics and Ancient Civilizations – Assyriology Leiden University, Faculty of Humanities 1 July 2019 Supervisor: Dr. J.G. Dercksen Second Reader: Dr. N.N. May Table of Content Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... 4 Chapter One: Introducing the Texts ............................................................................... 5 1.1 The Sources .......................................................................................................... 5 1.1.2 Main Sources ................................................................................................. 6 1.1.3 Secondary Sources ......................................................................................... 7 1.2 Problems with Date and Place .............................................................................. 8 1.3 History of Research ............................................................................................ 10 Chapter Two: The Nature of Death .............................................................................. 12 2.1 The God Dumuzi ............................................................................................... -

Rainbowtimesnews.Com FREE!

Year 2, Vol. 21 • April 3-30, 2008 The www.therainbowtimesnews.com FREE! CT News: CT TransAdvocacy NY News & Libby Post’s RainbowTimes Coalition: HB 5723 Act Lesbian Notions: Your LGBT News in Western MA, the Capital District of NY, Northern CT, & Southern VT p. 16 &17 p. 26 & 27 MARGARET CHO BUSINESS P. 12 NEW! RESTAURANT REVIEW P. 21 MAYA ANGELOU STANDS BY HILLARY CLINTON P. 27 VOTE WITH PRIDE: NOHO PRIDE KICKS OFF PRIDE SEASON, SEEKS VOLUNTEERS P. 13 SUICIDE MISSION: I CHOSE COWARDICE IN ANOTHER FORM P. 8 HB 1722: GENDER-BASED DISCRIMINATION and HATE CRIMES’ ACT— WHY IT MATTERS P. 3 Photo by: Austin Young Austin Photo by: 2 • April 3-30, 2008 • The Rainbow Times • www.therainbowtimesnews.com Opinions The Controversial Couch TRT endorses Sen. Hillary Clinton Lie back and listen. Then get up and do something By: Nicole C. Lashomb House. I will stop at that because when it By: Suzan Ambrose*/TRT Columnist ple would be strong aphrodisiacs, TRT Editor-in-Chief comes to the current President, I could fill in “Look! Up in the sky!! Is it a especially if the chemicals caused he Rainbow Times is pleased to the rest of the 31 pages of this edition of TRT, bird? A plane? No, it’s the gay homosexual behavior.” ($ 7.5 million announce our endorsement of and yet I would not be able to properly bomb!” Yes, the ‘gay bomb/poof bomb’ was were requested by the Air Force Lab Democratic presidential candidate, describe what this “Bush” has done to this T actually considered and researched by the to develop this bomb.) NY Senator Hillary Rodham Clinton.