Neo-Assyrian Palaces and the Creation of Courtly Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A RESOLUTION to Honor and Commend David L. Solomon Upon Being Named to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Business and Industry Hall of Fame

Filed for intro on 03/11/2002 HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 732 By Harwell A RESOLUTION to honor and commend David L. Solomon upon being named to the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants Business and Industry Hall of Fame. WHEREAS, it is fitting that the members of this General Assembly should salute those citizens who through their extraordinary efforts have distinguished themselves both in their chosen professions and as community leaders of whom we can all be proud; and WHEREAS, one such noteworthy person is David L. Solomon, Chairman, Chief Executive Officer and Director of NuVox Communications, who makes his home in Nashville, Tennessee; and WHEREAS, David Solomon embarked upon a career as an accountant when his father, Frazier Solomon, former Director of State Audit and Personnel Director of the Office of the Comptroller of the Treasury of the State of Tennessee, read bedtime stories to him from an accounting manual from the age of four; David grew up to be the husband of a CPA and the son-in-law of a CPA; and WHEREAS, Mr. Solomon earned a Bachelor of Science in accounting from David Lipscomb University in Nashville in 1981 and went to work for the public accounting firm of HJR0732 01251056 -1- KPMG Peat Marwick; during his thirteen years at KPMG Peat Marwick, he rose to the rank of partner, gaining experience in public and private capital markets, financial management and reporting; and WHEREAS, David Solomon left in 1994 to join Brooks Fiber Properties (BFP) as Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, as well as Chief Financial Officer, Secretary and Director of Brooks Telecommunications Corporation until it was acquired by BFP in January 1996; while at BFP, he was involved in all aspects of strategic development, raised over $1.6 billion in equity and debt, and built or acquired systems in 44 markets; and WHEREAS, since 1998, when BFP was sold to MCI WorldCom in a $3.4 billion transaction, Mr. -

The Emperor Charles VI and Spain (1700-1740)

19 April 2010 William O’Reilly (University of Cambridge) The Emperor Who Could Not Be King: The Emperor Charles VI and Spain (1700-1740) ‘Sad news’, wrote the Archduke Charles of Austria, self-styled King of Spain, on learning of the death of his elder brother, the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph I, in 1711. ‘From my house, only I remain. All falls to me.’ Terse as it may be, this obiter reveals the twin pillars of Charles VI’s imperial ideology: dynastic providence and universal dominion. In this expansive and absorbing paper, William O’Reilly offered an account of the career of the Emperor Charles VI as manqué King of Spain. The childless death of Charles II, the last Habsburg King of Spain, in 1700, ignited a succession crisis that engulfed Europe in conflict. Standard accounts of the War of the Spanish Succession treat the two pretenders, Philip Duc d’Anjou, grandson of Louis XIV, and the Archduke Charles, younger son of the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, as ciphers in a game of grand strategy. But Dr O’Reilly presented a compelling case for re- appraisal. His study of Charles revealed the decisive influence of personal ambition and court politics on the business of state formation in the early-eighteenth century. Arriving in Barcelona in the late summer of 1705, the Archduke was immediately proclaimed King Charles III of Spain throughout Catalonia. During his six years in Barcelona, he cultivated long-standing Catalan suspicions of Madrid (in Bourbon hands from 1707) to construct a Habsburg party among the Aragonese elite. -

Divine Help: 1 Samuel 27

Training Divine Help | GOD PROTECTS AND VINDICATES DAVID AGAIN What Do I Need to Know About the Passage? What’s the Big Idea? 1 Samuel 27:1-31:13 David has a second chance to kill Saul, but he spares him. Again, we learn the wonderful As we close out 1 Samuel, we cover a wide swath of narrative in this final lesson. truth that God protects His people, delivers You do not need to read chapter 31 during the study, but it is important that your them, and vindicates them as they trust in students know what it says. This narrative focuses on one theme: God pursues His Him. This lesson should lead us to experi- people and rejects those who reject Him. ence hope and encouragement because of God’s ultimate protection and vindication David Lives with the Philistines (27:1-28:2) through His Son Jesus. Immediately after experiencing deliverance from the LORD, David doubts God’s protection of his life. In 27:1, David says, “Now I shall perish one day by the hand of Saul. There is nothing better for me than that I should escape to the land of the Philistines.” What a drastic change of heart and attitude! David turns to his flesh as he worries whether God will continue to watch over him. Certainly we have experienced this before, but God has a perfect track record of never letting His people down. Make sure the group understands that God’s promises are always just that – promises! He can’t break them. What’s the Problem? We are selfish, impatient people who want David goes to King Achish for help, but this time, David doesn’t present himself as a situations to work out the way we want crazy man (see 21:10). -

Of a Princely Court in the Burgundian Netherlands, 1467-1503 Jun

Court in the Market: The ‘Business’ of a Princely Court in the Burgundian Netherlands, 1467-1503 Jun Hee Cho Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Jun Hee Cho All rights reserved ABSTRACT Court in the Market: The ‘Business’ of a Princely Court in the Burgundian Netherlands, 1467-1503 Jun Hee Cho This dissertation examines the relations between court and commerce in Europe at the onset of the modern era. Focusing on one of the most powerful princely courts of the period, the court of Charles the Bold, duke of Burgundy, which ruled over one of the most advanced economic regions in Europe, the greater Low Countries, it argues that the Burgundian court was, both in its institutional operations and its cultural aspirations, a commercial enterprise. Based primarily on fiscal accounts, corroborated with court correspondence, municipal records, official chronicles, and contemporary literary sources, this dissertation argues that the court was fully engaged in the commercial economy and furthermore that the culture of the court, in enacting the ideals of a largely imaginary feudal past, was also presenting the ideals of a commercial future. It uncovers courtiers who, despite their low rank yet because of their market expertise, were close to the duke and in charge of acquiring and maintaining the material goods that made possible the pageants and ceremonies so central to the self- representation of the Burgundian court. It exposes the wider network of court officials, urban merchants and artisans who, tied by marriage and business relationships, together produced and managed the ducal liveries, jewelries, tapestries and finances that realized the splendor of the court. -

Why Did Nebuchadnezzar II Destroy Ashkelon in Kislev 604 ...?

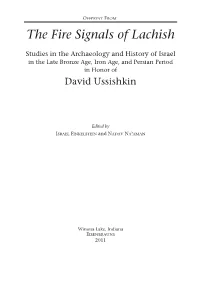

Offprint From The Fire Signals of Lachish Studies in the Archaeology and History of Israel in the Late Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Persian Period in Honor of David Ussishkin Edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Naʾaman Winona Lake, Indiana Eisenbrauns 2011 © 2011 by Eisenbrauns Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. www.eisenbrauns.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The fire signals of Lachish : studies in the archaeology and history of Israel in the late Bronze age, Iron age, and Persian period in honor of David Ussishkin / edited by Israel Finkelstein and Nadav Naʾaman. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-1-57506-205-1 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Israel—Antiquities. 2. Excavations (Archaeology)—Israel. 3. Bronze age— Israel. 4. Iron age—Israel. 5. Material culture—Palestine. 6. Palestine—Antiquities. 7. Ussishkin, David. I. Finkelstein, Israel. II. Naʾaman, Nadav. DS111.F57 2011 933—dc22 2010050366 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. †Ê Why Did Nebuchadnezzar II Destroy Ashkelon in Kislev 604 ...? Alexander Fantalkin Tel Aviv University Introduction The significance of the discovery of a destruction layer at Ashkelon, identified with the Babylonian assault in Kislev, 604 B.C.E, can hardly be overestimated. 1 Be- yond the obvious value of this find, which provides evidence for the policies of the Babylonian regime in the “Hatti-land,” it supplies a reliable chronological anchor for the typological sequencing and dating of groups of local and imported pottery (Stager 1996a; 1996b; Waldbaum and Magness 1997; Waldbaum 2002a; 2002b). -

OAS » Inter-American Juridical Committee (IAJC) » Annual Report

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES INTER-AMERICAN JURIDICAL COMMITTEE IAJC 63rd REGULAR SESSION OEA/Ser.Q/VI.34 August 4 to 29, 2003 CJI/doc.145/03 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 29 August 2003 Original: Spanish ANNUAL REPORT OF THE INTER-AMERICAN JURIDICAL COMMITTEE TO THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY 2003 ii iii EXPLANATORY NOTE Up until 1990, the OAS General Secretariat had published the Minutes of meetings and Annual Reports of the Inter-American Juridical Committee under the series classified as Reports and Recommendations. Starting in 1997, the Department of International Law of the Secretariat for Legal Affairs of the OAS General Secretariat again started to publish those documents, this time under the title Annual report of the Inter-American Juridical Committee to the General Assembly. Under the Classification manual for the OAS official records series, the Inter- American Juridical Committee is assigned the classification code OEA/Ser.Q, followed by CJI, to signify documents issued by this body, (see attached lists of resolutions and documents). iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED BY THE INTER-AMERICAN JURIDICAL COMMITTEE .......................... vii DOCUMENTS INCLUDED IN THIS ANNUAL REPORT ........................................................................ ix INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I ..............................................................................................................................................5 -

KINGSHIP and POLITICS in the LATE NINTH CENTURY Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Emp Ire

KINGSHIP AND POLITICS IN THE LATE NINTH CENTURY Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Emp ire SIMON MACLEAN publ ished by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge cb2 1rp, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge, cb2 2ru,UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011–4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Simon MacLean 2003 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2003 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typ eface Bembo 11/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data MacLean, Simon. Kingship and policy in the late ninth century : Charles the Fat and the end of the Carolingian Empire / Simon MacLean. p. cm. – (Cambridge studies in medieval life and thought ; 4th ser., 57) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-521-81945-8 1. Charles, le Gros, Emperor, 839–888. 2. France – Kings and rulers – Biography. 3. France – History – To 987. 4. Holy Roman Empire – History – 843–1273. I. Title. II. Series. DC77.8M33 2003 944.014092 –dc21 2003043471 isbn -

Tribute to Simon Sargon Shabbat Noach November 5, 2016 Rabbi David Stern

Tribute to Simon Sargon Shabbat Noach November 5, 2016 Rabbi David Stern When Simon was born in 1938 in Mumbai, the truth is he wasn’t the first Sargon. Of course, his father was named Benjamin Sargon, but if you know something about the history of Mesopotamia, you know that scholars estimate that there have been Sargons around for about forty-five centuries. So I thought maybe we could learn something about Simon by looking at his antecedent Sargons. One of them is mentioned in the Bible, in the Book of Isaiah. He is known as Sargon II, an Assyrian King of the 8th century BCE who took power by violent coup, and then completed the defeat of the Kingdom of Israel. That did not seem like the most noble exemplar, so I decided to look further. About 1200 years before Sargon II, there was Sargon I, which is a pretty long time to go without a King Sargon. And to make matters worse, Sargon I did not leave much of a footprint. He shows up in ancient lists of Assyrian kings, but that’s about it. Undeterred, we search on. And that’s what brings us to an Akkadian king of the 24th century BCE known as Sargon the Great. Now we’re getting somewhere. Because Sargon the Great was just that – a successful warrior, a model and powerful ruler who was known for listening to his subordinates. He creates a dynasty, and creates a model of leadership for centuries of Mesopotamian kings to follow. But while Sargon the Great gets us closer to what our Sargon means to us, it’s really not close enough. -

Acra Fortress, Built by Antiochus As He Sought to Quell a Jewish Priestly Rebellion Centered on the Temple

1 2,000-year-old fortress unearthed in Jerusalem after century-long search By Times of Israel staff, November 3, 2015, 2:52 pm http://www.timesofisrael.com/maccabean-era-fortress-unearthed-in-jerusalem-after-century-long- search/ Acra fortification, built by Hanukkah villain Antiochus IV Epiphanes, maintained Seleucid Greek control over Temple until its conquest by Hasmoneans in 141 BCE In what archaeologists are describing as “a solution to one of the great archaeological riddles in the history of Jerusalem,” researchers with the Israel Antiquities Authority announced Tuesday that they have found the remnants of a fortress used by the Seleucid Greek king Antiochus Epiphanes in his siege of Jerusalem in 168 BCE. A section of fortification was discovered under the Givati parking lot in the City of David south of the Old City walls and the Temple Mount. The fortification is believed to have been part of a system of defenses known as the Acra fortress, built by Antiochus as he sought to quell a Jewish priestly rebellion centered on the Temple. 2 Antiochus is remembered in the Jewish tradition as the villain of the Hanukkah holiday who sought to ban Jewish religious rites, sparking the Maccabean revolt. The Acra fortress was used by his Seleucids to oversee the Temple and maintain control over Jerusalem. The fortress was manned by Hellenized Jews, who many scholars believe were then engaged in a full-fledged civil war with traditionalist Jews represented by the Maccabees. Mercenaries paid by Antiochus rounded out the force. Lead sling stones and bronze arrowheads stamped with the symbol of the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, evidence of the attempts to conquer the Acra citadel in Jerusalem’s City of David in Maccabean days. -

Webb, Nigel (2004)

Webb, Nigel (2004) Settlement and integration in Scotland 1124-1214: local society and the development of aristocratic communities: with special reference to the Anglo-French settlement of the South East. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3535/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement and Integration in Scotland 1124-1214. Local Society and the Development of Aristocratic Communities: With Special Reference to the Anglo-French Settlement of the South East. Nigel Webb Ph.D. Department of Medieval History The University of Glasgow December 2004 Acknowledgements lowe my biggest debt of gratitude to my supervisors Professor David Bates and Dr. Dauvit Broun for their support and unfailing belief, patience and enthusiasm over the years. I am also indebted to my friend Anthony Vick for his invaluable help in charter Latin during the early years of my work. I also owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my wife's parents William and Shelagh Cowan not only for their support, but also for their patient proof reading of this thesis. -

Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland

Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland By Vidar Palsson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor John Lindow, Co-chair Professor Thomas A. Brady Jr., Co-chair Professor Maureen C. Miller Professor Carol J. Clover Fall 2010 Abstract Power and Political Communication. Feasting and Gift Giving in Medieval Iceland By Vidar Palsson Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor John Lindow, Co-chair Professor Thomas A. Brady Jr., Co-chair The present study has a double primary aim. Firstly, it seeks to analyze the sociopolitical functionality of feasting and gift giving as modes of political communication in later twelfth- and thirteenth-century Iceland, primarily but not exclusively through its secular prose narratives. Secondly, it aims to place that functionality within the larger framework of the power and politics that shape its applications and perception. Feasts and gifts established friendships. Unlike modern friendship, its medieval namesake was anything but a free and spontaneous practice, and neither were its primary modes and media of expression. None of these elements were the casual business of just anyone. The argumentative structure of the present study aims roughly to correspond to the preliminary and general historiographical sketch with which it opens: while duly emphasizing the contractual functions of demonstrative action, the backbone of traditional scholarship, it also highlights its framework of power, subjectivity, limitations, and ultimate ambiguity, as more recent studies have justifiably urged. -

Unit 7: Activities - the Habsburgs

Activites - The Habsburgs by Gema de la Torre is licensed under Unit 7: Activites – a Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional License The Habsburgs Unit 7: Activities - The Habsburgs Index 1. Origin of the house of Habsburg. ................................................................................................... 1 2. Charles I ......................................................................................................................................... 2 2.1. Inheritance of Charles I .......................................................................................................... 2 2.2. Internal Problems. .................................................................................................................. 3 2.3. International Relations ........................................................................................................... 4 3. Philip II .......................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. Philip II's Government ........................................................................................................... 5 4. Minor Austrias................................................................................................................................ 7 4.1. Philip III ................................................................................................................................. 8 4.2. Philip IV ................................................................................................................................