Church Architecture and Its Impact on Balinese Identity and Tourism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marginalization of Bali Traditional Architecture Principles

International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Culture Available online at https://sloap.org/journals/index.php/ijllc/ Vol. 6, No. 5, September 2020, pages: 10-19 ISSN: 2455-8028 https://doi.org/10.21744/ijllc.v6n5.975 Marginalization of Bali Traditional Architecture Principles a I Kadek Pranajaya b I Ketut Suda c I Wayan Subrata Article history: Abstract The traditional Balinese architecture principles have been marginalized and Submitted: 09 June 2020 are not following Bali Province Regulation No. 5 of 2005 concerning Revised: 18 July 2020 Building Architecture Requirements. In this study using qualitative analysis Accepted: 27 August 2020 with a critical approach or critical/emancipatory knowledge with critical discourse analysis. By using the theory of structure, the theory of power relations of knowledge and the theory of deconstruction, the marginalization of traditional Balinese architecture principles in hotel buildings in Kuta Keywords: Badung Regency is caused by factors of modernization, rational choice, Balinese architecture; technology, actor morality, identity, and weak enforcement of the rule of law. hotel building; The process of marginalization of traditional Balinese architecture principles marginalization; in hotel buildings in Kuta Badung regency through capital, knowledge-power principles; relations, agency structural action, and political power. The implications of traditional; the marginalization of traditional Balinese architecture principles in hotel buildings in Kuta Badung Regency have implications for the development of tourism, professional ethics, city image, economy, and culture of the community as well as for the preservation of traditional Balinese architecture. International journal of linguistics, literature and culture © 2020. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province (Indonesia) No 1194Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Fund for preparing the Nomination Cultural Landscape of Bali Province 30 June 2001 (Indonesia) Date received by the World Heritage Centre No 1194rev 31 January 2007 28 January 2011 Background This is a deferred nomination (32 COM, Quebec City, Official name as proposed by the State Party 2008). The Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana The World Heritage Committee adopted the following Philosophy decision (Decision 32 COM 8B.22): Location The World Heritage Committee, Province of Bali 1. Having examined Documents WHC-08/32.COM/8B Indonesia and WHC-08/32.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Defers the examination of the nomination of the Brief description Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, Indonesia, to the Five sites of rice terraces and associated water temples World Heritage List in order to allow the State Party to: on the island of Bali represent the subak system, a a) reconsider the choice of sites to allow a unique social and religious democratic institution of self- nomination on the cultural landscape of Bali that governing associations of farmers who share reflects the extent and scope of the subak system of responsibility for the just and efficient use of irrigation water management and the profound effect it has water needed to cultivate terraced paddy rice fields. had on the cultural landscape and political, social and agricultural systems of land management over at The success of the thousand year old subak system, least a millennia; based on weirs to divert water from rivers flowing from b) consider re-nominating a site or sites that display volcanic lakes through irrigation tunnels onto rice the close link between rice terraces, water temples, terraces carved out of the flanks of mountains, has villages and forest catchment areas and where the created a landscape perceived to be of great beauty and traditional subak system is still functioning in its one that is ecologically sustainable. -

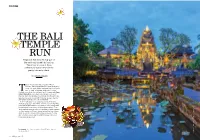

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

13543 Dwijendra 2020 E.Docx

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 13, Issue 5, 2020 Analysis of Symbolic Violence Practices in Balinese Vernacular Architecture: A case study in Bali, Indonesia Ngakan Ketut Acwin Dwijendraa, I Putu Gede Suyogab, aUdayana University, Bali, Indonesia, bSekolah Tinggi Desain Bali, Indonesia, Email: [email protected], [email protected] This study debates the vernacular architecture of Bali in the Middle Bali era, which was strongly influenced by social stratification discourse. The discourse of social stratification is a form of symbolic power in traditional societies. Through discourse, the power practices of the dominant group control the dominated, and such dominance is symbolic. Symbolic power will have an impact on symbolic violence in cultural practices, including the field of vernacular architecture. This study is a qualitative research with an interpretive descriptive method. The data collection is completed from literature, interviews, and field observations. The theory used is Pierre Bourdieu's Symbolic Violence Theory. The results of the study show that the practice of symbolic violence through discourse on social stratification has greatly influenced the formation or appearance of residential architecture during the last six centuries. This symbolic violence takes refuge behind tradition, the social, and politics. The forms of symbolic violence run through the mechanism of doxa, but also receive resistance symbolically through heterodoxa. Keywords: Balinese, Vernacular, Architecture, Symbolic, Violence. Introduction Symbolic violence is a term known in Pierre Bourdieu's thought, referring to the use of power over symbols for violence. Violence, in this context, is understood not in the sense of radical physical violence, for example being beaten, open war, or the like, but more persuasive. -

Understanding the Sai Baba Movement in Bali As an Urban Phenomenon*

Workplace and Home: Understanding the Sai Baba Movement in Bali as an Urban Phenomenon* Gde Dwitya Arief Metera** Abstract Since the transition to post-New Order Indonesia in 1998, new religious movements such as Sai Baba have become popular in Bali. In contrast with the New Order era when Sai Baba was under strict scrutiny, these groups are now warmly accepted by a far wider audience and especially from educated affluent urbanites. In this paper, I discuss several factors that make Sai Baba movement generally an urban phenomenon. I ask how change taking place in Bali regarding the economic and demographic context may have contributed to the people’s different mode of religious articulation. The economic transformation from agricultural economy to modern industrial economy in Bali has changed people’s occupations and forced urbanization. I argue that the transformation also creates two emerging cultural spaces of Workplace in the city and Home in the villages of origin. Workplace is where people are bound to modern disposition of time and Home is where people are tied to traditional disposition of time. These two cultural spaces determine people’s mode of religious articulation. As people move from their villages of origin to the city, they also adopt a new mode of religious articulation in an urban context. I suggest that to understand the emergence of new religions and new mode of religious articulation in Bali we have to look at specific transformations at the economic and demographic level. ____________ * This paper was presented at the 6th Singapore Graduate Forum on Southeast Asian Studies, Asia Research Institute, Singapore 13-15 July 2011. -

Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from The

https://pratujournal.org ISSN 2634-176X Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from the Northern Indian Subcontinent to 11th-Century Bali Durga Mahiṣāsuramardinī dalam konteks agama Buddha Tantrayana dari Subkontinen India Utara dan Bali pada abad ke-11 Ambra CALO Department of Archaeology and Natural History, The Australian National University [email protected] Translation by: Christa HARDJASAPUTRA, Alphawood Alumna, Postgraduate Diploma of Asian Art, SOAS University of London Edited by: Ben WREYFORD, Pratu Editorial Team Received 1 April 2019; Accepted 1 November 2019; Published 8 May 2020 Funding statement: The research for this study was funded by the Southeast Asian Art Academic Programme, Academic Support Fund (SAAAP #049), at SOAS University of London. The author declares no known conflict of interest. Abstract: This study examines the significance of the originally Hindu goddess Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā slaying the buffalo demon) in Tantric Buddhist temple contexts of the 8th–11th century in Afghani- stan and northeastern India, and 11th-century Bali. Taking a cross-regional approach, it considers the genesis of Tantric Buddhism, its transmission to Indonesia, and its significance in Bali during the 10th–11th century. Drawing primarily on archaeological and iconographic evidence, it suggests that Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī is likely to have reached Bali as part of a late 10th–11th century phase of renewed transmission of Tantric Buddhism from the northeastern Indian subcontinent to Indonesia, following an initial late 7th–8th century phase. Keywords: Bali, Durgā, Heruka, Mahiṣāsuramardinī, maritime networks, Padang Lawas, Tantric Buddhism, Tantric Śaivism, Tapa Sardār, Uḍḍiyāna, Vajrayāna, Vikramaśīla, Warmadewa Abstrak: Penelitian ini melihat signifikansi dari dewi Hindu Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā membunuh iblis kerbau) dalam konteks kuil Buddha Tantrayana pada abad ke-8 hingga ke-11 di Afghanistan dan timur laut India, serta abad ke-11 di Bali. -

Religion in Bali by C. Hooykaas

Religion in Bali by C. Hooykaas Contents Acknowledgments Bibliography 1. Orientation 2. First Acquaintance 3. Kanda Mpat 4. Some Dangers 5. Impurity 6. Demons 7. Black Magic 8. Holy Water(s) 9. Priests: Pamangku 10. Priests: Padanda 11. Priests: Amangku Dalang 12. Priests: Sengguhu 13. Priests: Balian 14. Priests: Dukuh 15. Trance 16. Laymen 17. Humble Things 18. Rites de Passage 19. Burial and Cremation 20. The Playful Mind 21. Cows Not Holy 22. Legends to the Illustrations 23. Plates at the end of the book Acknowledgements First of all I thank my wife who from the outset encouraged me and advised me. In the field of photography I received help from: Drs. P. L. Dronkers, Eindhoven: a, b 1. Prof. Dr. J. Ensink, University of Groningen: n 1, n 2. Mrs. Drs. Hedi Hinzler, Kern Institute, Leiden. d 2, m 2, u 1 5, w 1, w 2, x 2, x 3. Mr. Mark Hobart, M. A. University of London: k 1, k 4, o 4, o 5. Mrs. Drs. C. M. C. Hooykaas van Leeuwen Boomkamp: g 3, k 2, k 3, m 3, o 1, o 2, p 1 3, q 1 5, t 2, t 5, v 1 4, w 3 4, x 1, x 4. Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal , Land en Volkenkunde, Leiden: f 1. (Gedong) Kirtya, Singaraja, Bali, Indonesia: c 1 3, z 1 (original drawings). Library of the University, Leiden: h 1 6, i 1 7, j 1 8. Museum voor Volkenkunde, Delft: d 3, d 4. Rijks Museum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden: f 2, r 1, y 2. -

Changing a Hindu Temple Into the Indrapuri Mosque in Aceh: the Beginning of Islamisation in Indonesia – a Vernacular Architectural Context

This paper is part of the Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art (IHA 2016) www.witconferences.com Changing a Hindu temple into the Indrapuri Mosque in Aceh: the beginning of Islamisation in Indonesia – a vernacular architectural context Alfan1 , D. Beynon1 & F. Marcello2 1Faculty of Science, Engineering and Built Environment, Deakin University, Australia 2Faculty of Health Arts and Design, Swinburne University, Australia Abstract This paper elucidates on the process of Islamisation in relation to vernacular architecture in Indonesia, from its beginning in Indonesia’s westernmost province of Aceh, analysing this process of Islamisation from two different perspectives. First, it reviews the human as the receiver of Islamic thought. Second, it discusses the importance of the building (mosque or Mushalla) as a human praying place that is influential in conducting Islamic thought and identity both politically and culturally. This paper provides evidence for the role of architecture in the process of Islamisation, by beginning with the functional shift of a Hindu temple located in Aceh and its conversion into the Indrapuri Mosque. The paper argues that the shape of the Indrapuri Mosque was critical to the process of Islamisation, being the compositional basis of several mosques in other areas of Indonesia as Islam developed. As a result, starting from Aceh but spreading throughout Indonesia, particularly to its Eastern parts, Indonesia’s vernacular architecture was developed by combining local identity with Islamic concepts. Keywords: mosque, vernacular architecture, human, Islamic identity, Islamisation. WIT Transactions on The Built Environment, Vol 159, © 2016 WIT Press www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3509 (on-line) doi:10.2495/IHA160081 86 Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art 1 Introduction Indonesia is an archipelago country, comprising big and small islands. -

The Byar: an Ethnographic and Empirical Study of a Balinese Musical Moment

The Byar: An Ethnographic and Empirical Study of a Balinese Musical Moment Andy McGraw with Christine Kohnen INTRODUCTION HE repertoire of the Balinese gamelan gong kebyar ensemble (see Tenzer 2000 and the T glossary provided in Appendix A) is marked by virtuosic, unmetered tutti passages, referred to as kebyar, that often introduce pieces or function as transitions within compositions. The kebyar itself often begins with a sudden, fortissimo byar, a single, tutti chord that is performed by the majority of the ensemble.1 The sheer virtuosity and power of this famous repertoire is encapsulated in the expert execution of a byar, in which twenty to thirty musicians, without the aid of notation, a conductor, or beat entrainment, synchronize to produce a shockingly precise and loud eruption of sound. During several fieldwork sessions in Bali over the past decade, McGraw has occasionally heard expert performers and composers claim that they could identify regional ensembles simply by hearing them perform a single byar. Several informants suggested that the relative temporal alignment of instrumental onsets was the primary distinguishing characteristic of a byar. This would be the equivalent to being able to identify symphony orchestras by hearing, for example, only the first sforzando chord of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. This paper concerns the expression and recognition of group identity as conveyed through performance and listening. Is the temporal structuring of an ensemble’s byar indicative of their musical identity? What is the minimal temporal scale of the expression of such identity? If such differences are not empirically evident or statistically significant, what implications does this have for Balinese conceptions of musical identity? What does this approach reveal about Balinese and non-Balinese listening habits and abilities and how they overlap or diverge? Because these questions are extremely complex we have limited our investigation to the smallest building block of the kebyar repertoire: the musical moment of the byar. -

Diversity of Cultural Elements at the Reliefs of Pura Desa Lan Puseh in Sudaji Village, Northern Bali

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 197 5th Bandung Creative Movement International Conference on Creative Industries 2018 (5th BCM 2018) Diversity of Cultural Elements at The Reliefs of Pura Desa Lan Puseh in Sudaji Village, Northern Bali I Dewa Alit Dwija Putra1*, Sarena Abdullah2 1School of Creative Industries-Telkom University, Indonesia 2School of Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Abstract. Northern Bali as a coastal region is the path of global trade traffic from the beginning of the Christian Calendar so that the relations of Balinese people with the outside world are so intense and have an impact on the socio-cultural changes of the society, especially the of ornament art. Ornaments applied to temple buildings in Bali are the result of classical Hindu culture, but in the reliefs of the temple of Desa Lan Puseh in the village of Sudaji, North Bali describes multicultural cultures such as Hinduism, Buddhism, China, as well as Persia as well as elements of European culture. The formation of these ornaments is certainly through a long process involving external and internal factors. The process of dialogue and acculturation of foreign cultures towards local culture gives change and forms new idioms that leave their original forms, as well as new functions, symbols, and meanings in Balinese society. This research uses the socio-historical qualitative method to write chronologically the inclusion of the influences of foreign cultural elements on Balinese social life with visual analysis through the stages to be able to describe and reveal the transformation of relief forms in the temple. This paper also proves that elements of foreign culture such as Islam and European had enriched the ornamental arts of Balinese tradition. -

Candi, Space and Landscape

Degroot Candi, Space and Landscape A study on the distribution, orientation and spatial Candi, Space and Landscape organization of Central Javanese temple remains Central Javanese temples were not built anywhere and anyhow. On the con- trary: their positions within the landscape and their architectural designs were determined by socio-cultural, religious and economic factors. This book ex- plores the correlations between temple distribution, natural surroundings and architectural design to understand how Central Javanese people structured Candi, Space and Landscape the space around them, and how the religious landscape thus created devel- oped. Besides questions related to territory and landscape, this book analyzes the structure of the built space and its possible relations with conceptualized space, showing the influence of imported Indian concepts, as well as their limits. Going off the beaten track, the present study explores the hundreds of small sites that scatter the landscape of Central Java. It is also one of very few stud- ies to apply the methods of spatial archaeology to Central Javanese temples and the first in almost one century to present a descriptive inventory of the remains of this region. ISBN 978-90-8890-039-6 Sidestone Sidestone Press Véronique Degroot ISBN: 978-90-8890-039-6 Bestelnummer: SSP55960001 69396557 9 789088 900396 Sidestone Press / RMV 3 8 Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden CANDI, SPACE AND LANDscAPE Sidestone Press Thesis submitted on the 6th of May 2009 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Leiden University. Supervisors: Prof. dr. B. Arps and Prof. dr. M.J. Klokke Referee: Prof. dr. J. Miksic Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde No. -

Traditional Balinese Architecture: from Cosmic to Modern

SHS Web of Conferences 76, 01047 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20207601047 ICSH 2019 Traditional Balinese Architecture: From Cosmic to Modern Ronald Hasudungan Irianto Sitinjak*, Laksmi Kusuma Wardani, and Poppy Firtatwentyna Nilasari Interior Design Department, Faculty of Art and Design, Petra Christian University, Siwalankerto 121–131, Surabaya 60236, Indonesia Abstract. Balinese architecture often considers aspects of climate and natural conditions as well as environmental social life. This is to obtain a balance in the cosmos, between human life (bhuana alit / microcosm) and its natural environment (bhuana agung /macrocosm). However, Bali's progress in tourism has changed the way of life of the people, which is in line with Parsons Theory of Structural Functionalism, that if there is a change in the function of one part of an institution or structure in a social system, it will affect other parts, eventually affecting the condition of the social system as a whole. The shift in perspectives has caused structural and functional changes in Balinese architecture. The building design or architecture that emerges today is no longer oriented towards cosmic factors but is oriented towards modern factors, developing in the interests of tourism, commercialization, and lifestyle. The change has had an impact on spatial planning, building orientation, architectural appearance, interior furnishings and local regulations in architecture. In order to prevent Balinese architecture from losing its authenticity in its original form, which is full of spiritual meaning and local Balinese traditions, it is necessary to have a guideline on the specifications of Balinese architectural design that combines elements of aesthetics, comfort, technology, and spirituality.