Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 02:04:41PM Via Free Access Plate 7.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUMMER Programme in Southeast Asian Art History & Conservation

@Hadi Sidomulyo SUMMER Programme in southeast asian art history & conservation FOCUS: PREMODERN JAVA Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre, ISEAS–Yusof Ishak institute (nsc-iseas) School of oriental and african studies (soas) universitas surabaya (ubaya) Trawas, East Java (Indonesia), July 23–2 August 2016 SUMMER Programme Lecturers Teaching Schedule A mix of 10 Indonesian and European experts will form The five days teaching schedule will include four 2-hour ses- the pool of lecturers. It includes Dr. Andrea Acri (NSC- sions per day (two in the morning and two in the afternoon). in southeast asian art history & conservation ISEAS & Nalanda University), Dr. Helene Njoto (NSC- Other speakers and students will be invited to present their on- ISEAS), Dr. Nigel Bullough (aka Hadi Sidomulyo, Ubaya), going research in some evenings. FOCUS: PREMODERN JAVA Dr. Lutfi Ismail (Univ. Malang), Adji Damais (BKKI, Indo nesian Art Agency Cooperation), Dr. Peter Sharrock and Nalanda Sriwijaya Center at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute (NSC-ISEAS), School of Oriental and Swati Chemburkar (SOAS), Prof. Dr. Marijke Klokke African Studies (SOAS) & University of Surabaya (UBAYA) (Leiden University), Dr Hanna Maria Szczepanowska and Sylvia Haliman (Heritage Conservation Center, HCC, Art history tour programme The programme will commence with a one-day tour of Trawas/ Singapore). The lectures will focus on both theoretical and Trawas, East Java, July 23–2 August 2016 Mount Penanggungan, and end with a three-day tour to temples, historical aspects of Javanese Art History and related disci- museums and relevant archaeological sites across East Java Project Coordinators: Andrea Acri, Helene Njoto, Peter Sharrock plines, and will include an element of practical and metho- (i.e. -

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province (Indonesia) No 1194Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Fund for preparing the Nomination Cultural Landscape of Bali Province 30 June 2001 (Indonesia) Date received by the World Heritage Centre No 1194rev 31 January 2007 28 January 2011 Background This is a deferred nomination (32 COM, Quebec City, Official name as proposed by the State Party 2008). The Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana The World Heritage Committee adopted the following Philosophy decision (Decision 32 COM 8B.22): Location The World Heritage Committee, Province of Bali 1. Having examined Documents WHC-08/32.COM/8B Indonesia and WHC-08/32.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Defers the examination of the nomination of the Brief description Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, Indonesia, to the Five sites of rice terraces and associated water temples World Heritage List in order to allow the State Party to: on the island of Bali represent the subak system, a a) reconsider the choice of sites to allow a unique social and religious democratic institution of self- nomination on the cultural landscape of Bali that governing associations of farmers who share reflects the extent and scope of the subak system of responsibility for the just and efficient use of irrigation water management and the profound effect it has water needed to cultivate terraced paddy rice fields. had on the cultural landscape and political, social and agricultural systems of land management over at The success of the thousand year old subak system, least a millennia; based on weirs to divert water from rivers flowing from b) consider re-nominating a site or sites that display volcanic lakes through irrigation tunnels onto rice the close link between rice terraces, water temples, terraces carved out of the flanks of mountains, has villages and forest catchment areas and where the created a landscape perceived to be of great beauty and traditional subak system is still functioning in its one that is ecologically sustainable. -

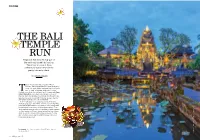

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Tracing Vishnu Through Archeological Remains at the Western Slope of Mount Lawu

KALPATARU, Majalah Arkeologi Vol. 29 No. 1, Mei 2020 (15-28) TRACING VISHNU THROUGH ARCHEOLOGICAL REMAINS AT THE WESTERN SLOPE OF MOUNT LAWU Menelusuri Jejak Wisnu pada Tinggalan Arkeologi di Lereng Gunung Lawu Heri Purwanto1 and Kadek Dedy Prawirajaya R.2 1Archaeology Alumni in Archaeology Department, Udayana University Jl. Pulau Nias No. 13, Sanglah, Denpasar-Bali [email protected] 2Lecturer in Archaeology Department, Udayana University Jl. Pulau Nias No. 13, Sanglah, Denpasar-Bali [email protected] Naskah diterima : 5 Mei 2020 Naskah diperiksa : 27 Mei 2020 Naskah disetujui : 4 Juni 2020 Abstract. To date, The West Slope area of Mount Lawu has quite a lot of archaeological remains originated from Prehistoric Period to Colonial Period. The number of religious shrines built on Mount Lawu had increased during the Late Majapahit period and were inhabited and used by high priests (rsi) and ascetics. The religious community was resigned to a quiet place, deserted, and placed far away on purpose to be closer to God. All religious activities were held to worship Gods. This study aims to trace Vishnu through archaeological remains. Archaeological methods used in this study are observation, description, and explanation. Result of this study shows that no statue has ever been identified as Vishnu. However, based on archeological data, the signs or symbols that indicated the existence of Vishnu had clearly been observed. The archeological evidences are the tortoise statue as a form of Vishnu Avatar, Garuda as the vehicle of Vishnu, a figure riding Garuda, a figure carrying cakra (the main weapon of Vishnu), and soles of his feet (trivikrama of Vishnu). -

Educational Tourism As the Conceptual Age in the University of Surabaya

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research (ASSEHR), volume 186 15th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2018) Educational Tourism as the conceptual age in the University of Surabaya Veny Megawati University of Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia ABSTRACT : In many major cities in a developed country, a green open space is being promoted as a vaca- tion destination. Besides, the government in the cities in developed countries also provides a museum that is neat and integrated with Simulation Park and playground for children. However, many green open spaces have turned into modern tourism places like shopping malls which may encourage children to be materialistic. To address this issue, parents can actually teach their children any other educational models that are oriented in nature. The nature-oriented models allow childer to create, explore, and stimulate cognitive development, also affective for their motorist skill. The University of Surabaya as one of the best private universities has designed a nature-oriented educational program called “Educational Tourism “.This program was made based on the conceptual age that consists of design, story, symphony, empathy, play, and meaning. Keywords: the conceptual age, educational tourism, University Of Surabaya materialistic education, parents can actually offer their children any other educational models that are 1 INTRODUCTION oriented in nature. On these green open areas, children are not only The growth of tourism these days has had a signifi- provided with an entertainment, but also the chance cant enhancement. The trends of the increasing to be creative, to explore, and of course, it can number of needs of traveling by Indonesians can be stimulate their cognitive growth and motorist affec- seen from the rising trends of those travelers in the tivity. -

Remote Sensing Analysis Using Landsat 8 Data for Lithological Mapping - a Case Study

nd 90 The 2 International Seminar on Science and Technology August 2nd 2016, Postgraduate Program Institut Teknologi Sepuluh Nopember, Surabaya, Indonesia Remote Sensing Analysis Using Landsat 8 Data For Lithological Mapping - A Case Study In Mount Penanggungan, East Java, Indonesia Hendra Bahar1, and Muhammad Taufik2 Abstract Mount Penanggungan is one of the volcanoes that located in East Java Province, Indonesia, with the current II. METHOD status is a sleeping volcano. Although Mount Penanggungan is not active, it still make an interesting investigation in Top of Mount Penanggungan are 1.653 meters from sea geological survey, especially to identify the lithological units, level, located in East Java Province, Indonesia, between 2 due that less researchers took place in Mount Penanggungan. (two) district, Mojokerto District in western part, and Geological survey and investigaton can describes the Pasuruan District in eastern part. Latitude is 07°36'50" of information about physically condition of some land or region, South Latitude and longitude is 112°37'10" of East with the result is Lithological Map of Mount Penanggungan. Longitude. Remote sensing imagery, such as Landsat 8 Satellite imagery Data that be use in this study are; Geological Map of data series has been used widely in geology for mapping Malang Sheet scale 1:100.000, Indonesian Surface Map lithology in general. Remote sensing provides information of scale 1:25.000, and Landsat 8 Satellite imagery data. the properties of the surface exploration targets that is potential in mapping lithological units. Remote sensing The Landsat 8 image used in this study (path 118 and technique are one of the standard procedures in exploration row 65) was captured on October 22nd, 2015 under geology, due to it is high efficiency and low cost. -

Wander-Lust--Heritage-As-Identity.Pdf

14 September 2016 Universitas Surabaya - To Be The First University in Heart and Mind http://www.ubaya.ac.id Wander Lust: Heritage as identity East Java has landscapes to challenge the adventurous, cultural riches to dazzle the curious–and one magic mountain that harbors a great storehouse of ancient arts and mysteries. Duncan Graham reports from Trawas in the Majapahit heartlands. On Jan. 17, Nigel Bullough tumbled down a ravine. It was a defining though agonizing moment in the explorer’s 44-year career in Indonesia. The British-born historian, who uses the nom d’archeologie Hadi Sidomulyo, was seeking centuries-old sites on East Java’s Mount Penanggungan when he fell. He was saved when his camera strap snagged the shrubbery. But his left arm was jerked from its socket and the bone fractured. It took his friends five hours to get him down the mountain, and a further hour’s slow drive over rough roads to reach a police hospital. A surgeon dashed in from afar in the early hours. The treatment was excellent, Sidomulyo said more than six months after the accident. My arm is almost back to normal. The mountain had opened up and given us so much. It briefly revealed its secrets and now it was time to close. And next day it started to rain. Penanggungan was telling me that it was time to sit down and work on our discoveries. These discoveries have been extraordinary. More than 130 previously uncharted sites have been found by Sidomulyo and his colleagues, including Malang State University lecturer Ismail Lutfi. -

JURNAL RISET KEFARMASIAN INDONESIA Adalah Jurnal Yang Diterbitkan Online Dan Diterbitkan Dalam Bentuk Cetak

JURNAL RISET KEFARMASIAN INDONESIA adalah jurnal yang diterbitkan online dan diterbitkan dalam bentuk cetak. Jurnal ini diterbitkan 3 kali dalam 1 tahun (Januari, Mei dan September). Jurnal ini diterbitkan oleh APDFI (Asosiasi Pendidikan Diploma Farmasi Indonesia). Lingkup jurnal ini meliputi Organisasi Farmasi, Kedokteran, Kimia Organik Sintetis, Kimia Organik Bahan Alami, Biokimia, Analisis Kimia, Kimia Fisik, Biologi, Mikrobiologi, Kultur Jaringan, Botani dan hewan yang terkait dengan produk farmasi, Keperawatan, Kebidanan, Analis Kesehatan, Nutrisi dan Kesehatan Masyarakat. ALAMAT REDAKSI : APDFI (Asosiasi Pendidikan Diploma Farmasi Indonesia) Jl. Buaran II No. 30 A, I Gusti Ngurah Rai, Klender Jakarta Timur, Indonesia Telp. 021 - 86615593, 4244486. Email : [email protected] (ISSN Online) : 2655 – 8289 (ISSN Cetak) : 2655 – 131X TIM EDITOR Advisor : Dra. Yusmaniar, M.Biomed, Apt, Ketua Umum APDFI Yugo Susanto, M.Farm., Apt, Wakil Ketua APDFI Leonov Rianto, M.Farm., Apt, Sekjen APDFI Editors in Chief : Supomo, M.Si., Apt , STIKES Samarinda, Indonesia Editor Board Member : Dr. Entris Sutrisno., M.HkKes., Apt (STFB Bandung) Imam Bagus Sumantri, S.Farm.,M.Si.,Apt (USU, Medan) Ernanin Dyah Wijayanti, S.Si., M.P (Akfar Putera Indonesia, Malang) Ika Agustina,S.Si, M.Farm (Akfar IKIFA, Jakarta) Reviewer : Prof. Muchtaridi, M.Si.,Ph.D, Apt (Universitas Padjajaran, Bandung) Abdi Wira Septama, Ph.D., Apt (Pusat Penelitian Kimia, PDII LIPI) Harlinda Kuspradini, Ph.D (Universitas Mulawarman, Samarinda) Dr. Entris Sutrisno., -

Understanding the Sai Baba Movement in Bali As an Urban Phenomenon*

Workplace and Home: Understanding the Sai Baba Movement in Bali as an Urban Phenomenon* Gde Dwitya Arief Metera** Abstract Since the transition to post-New Order Indonesia in 1998, new religious movements such as Sai Baba have become popular in Bali. In contrast with the New Order era when Sai Baba was under strict scrutiny, these groups are now warmly accepted by a far wider audience and especially from educated affluent urbanites. In this paper, I discuss several factors that make Sai Baba movement generally an urban phenomenon. I ask how change taking place in Bali regarding the economic and demographic context may have contributed to the people’s different mode of religious articulation. The economic transformation from agricultural economy to modern industrial economy in Bali has changed people’s occupations and forced urbanization. I argue that the transformation also creates two emerging cultural spaces of Workplace in the city and Home in the villages of origin. Workplace is where people are bound to modern disposition of time and Home is where people are tied to traditional disposition of time. These two cultural spaces determine people’s mode of religious articulation. As people move from their villages of origin to the city, they also adopt a new mode of religious articulation in an urban context. I suggest that to understand the emergence of new religions and new mode of religious articulation in Bali we have to look at specific transformations at the economic and demographic level. ____________ * This paper was presented at the 6th Singapore Graduate Forum on Southeast Asian Studies, Asia Research Institute, Singapore 13-15 July 2011. -

Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from The

https://pratujournal.org ISSN 2634-176X Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from the Northern Indian Subcontinent to 11th-Century Bali Durga Mahiṣāsuramardinī dalam konteks agama Buddha Tantrayana dari Subkontinen India Utara dan Bali pada abad ke-11 Ambra CALO Department of Archaeology and Natural History, The Australian National University [email protected] Translation by: Christa HARDJASAPUTRA, Alphawood Alumna, Postgraduate Diploma of Asian Art, SOAS University of London Edited by: Ben WREYFORD, Pratu Editorial Team Received 1 April 2019; Accepted 1 November 2019; Published 8 May 2020 Funding statement: The research for this study was funded by the Southeast Asian Art Academic Programme, Academic Support Fund (SAAAP #049), at SOAS University of London. The author declares no known conflict of interest. Abstract: This study examines the significance of the originally Hindu goddess Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā slaying the buffalo demon) in Tantric Buddhist temple contexts of the 8th–11th century in Afghani- stan and northeastern India, and 11th-century Bali. Taking a cross-regional approach, it considers the genesis of Tantric Buddhism, its transmission to Indonesia, and its significance in Bali during the 10th–11th century. Drawing primarily on archaeological and iconographic evidence, it suggests that Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī is likely to have reached Bali as part of a late 10th–11th century phase of renewed transmission of Tantric Buddhism from the northeastern Indian subcontinent to Indonesia, following an initial late 7th–8th century phase. Keywords: Bali, Durgā, Heruka, Mahiṣāsuramardinī, maritime networks, Padang Lawas, Tantric Buddhism, Tantric Śaivism, Tapa Sardār, Uḍḍiyāna, Vajrayāna, Vikramaśīla, Warmadewa Abstrak: Penelitian ini melihat signifikansi dari dewi Hindu Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā membunuh iblis kerbau) dalam konteks kuil Buddha Tantrayana pada abad ke-8 hingga ke-11 di Afghanistan dan timur laut India, serta abad ke-11 di Bali. -

Religion in Bali by C. Hooykaas

Religion in Bali by C. Hooykaas Contents Acknowledgments Bibliography 1. Orientation 2. First Acquaintance 3. Kanda Mpat 4. Some Dangers 5. Impurity 6. Demons 7. Black Magic 8. Holy Water(s) 9. Priests: Pamangku 10. Priests: Padanda 11. Priests: Amangku Dalang 12. Priests: Sengguhu 13. Priests: Balian 14. Priests: Dukuh 15. Trance 16. Laymen 17. Humble Things 18. Rites de Passage 19. Burial and Cremation 20. The Playful Mind 21. Cows Not Holy 22. Legends to the Illustrations 23. Plates at the end of the book Acknowledgements First of all I thank my wife who from the outset encouraged me and advised me. In the field of photography I received help from: Drs. P. L. Dronkers, Eindhoven: a, b 1. Prof. Dr. J. Ensink, University of Groningen: n 1, n 2. Mrs. Drs. Hedi Hinzler, Kern Institute, Leiden. d 2, m 2, u 1 5, w 1, w 2, x 2, x 3. Mr. Mark Hobart, M. A. University of London: k 1, k 4, o 4, o 5. Mrs. Drs. C. M. C. Hooykaas van Leeuwen Boomkamp: g 3, k 2, k 3, m 3, o 1, o 2, p 1 3, q 1 5, t 2, t 5, v 1 4, w 3 4, x 1, x 4. Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal , Land en Volkenkunde, Leiden: f 1. (Gedong) Kirtya, Singaraja, Bali, Indonesia: c 1 3, z 1 (original drawings). Library of the University, Leiden: h 1 6, i 1 7, j 1 8. Museum voor Volkenkunde, Delft: d 3, d 4. Rijks Museum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden: f 2, r 1, y 2. -

The Byar: an Ethnographic and Empirical Study of a Balinese Musical Moment

The Byar: An Ethnographic and Empirical Study of a Balinese Musical Moment Andy McGraw with Christine Kohnen INTRODUCTION HE repertoire of the Balinese gamelan gong kebyar ensemble (see Tenzer 2000 and the T glossary provided in Appendix A) is marked by virtuosic, unmetered tutti passages, referred to as kebyar, that often introduce pieces or function as transitions within compositions. The kebyar itself often begins with a sudden, fortissimo byar, a single, tutti chord that is performed by the majority of the ensemble.1 The sheer virtuosity and power of this famous repertoire is encapsulated in the expert execution of a byar, in which twenty to thirty musicians, without the aid of notation, a conductor, or beat entrainment, synchronize to produce a shockingly precise and loud eruption of sound. During several fieldwork sessions in Bali over the past decade, McGraw has occasionally heard expert performers and composers claim that they could identify regional ensembles simply by hearing them perform a single byar. Several informants suggested that the relative temporal alignment of instrumental onsets was the primary distinguishing characteristic of a byar. This would be the equivalent to being able to identify symphony orchestras by hearing, for example, only the first sforzando chord of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. This paper concerns the expression and recognition of group identity as conveyed through performance and listening. Is the temporal structuring of an ensemble’s byar indicative of their musical identity? What is the minimal temporal scale of the expression of such identity? If such differences are not empirically evident or statistically significant, what implications does this have for Balinese conceptions of musical identity? What does this approach reveal about Balinese and non-Balinese listening habits and abilities and how they overlap or diverge? Because these questions are extremely complex we have limited our investigation to the smallest building block of the kebyar repertoire: the musical moment of the byar.