Understanding the Sai Baba Movement in Bali As an Urban Phenomenon*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province (Indonesia) No 1194Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Fund for preparing the Nomination Cultural Landscape of Bali Province 30 June 2001 (Indonesia) Date received by the World Heritage Centre No 1194rev 31 January 2007 28 January 2011 Background This is a deferred nomination (32 COM, Quebec City, Official name as proposed by the State Party 2008). The Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana The World Heritage Committee adopted the following Philosophy decision (Decision 32 COM 8B.22): Location The World Heritage Committee, Province of Bali 1. Having examined Documents WHC-08/32.COM/8B Indonesia and WHC-08/32.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Defers the examination of the nomination of the Brief description Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, Indonesia, to the Five sites of rice terraces and associated water temples World Heritage List in order to allow the State Party to: on the island of Bali represent the subak system, a a) reconsider the choice of sites to allow a unique social and religious democratic institution of self- nomination on the cultural landscape of Bali that governing associations of farmers who share reflects the extent and scope of the subak system of responsibility for the just and efficient use of irrigation water management and the profound effect it has water needed to cultivate terraced paddy rice fields. had on the cultural landscape and political, social and agricultural systems of land management over at The success of the thousand year old subak system, least a millennia; based on weirs to divert water from rivers flowing from b) consider re-nominating a site or sites that display volcanic lakes through irrigation tunnels onto rice the close link between rice terraces, water temples, terraces carved out of the flanks of mountains, has villages and forest catchment areas and where the created a landscape perceived to be of great beauty and traditional subak system is still functioning in its one that is ecologically sustainable. -

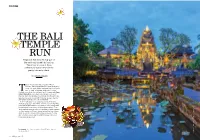

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from The

https://pratujournal.org ISSN 2634-176X Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from the Northern Indian Subcontinent to 11th-Century Bali Durga Mahiṣāsuramardinī dalam konteks agama Buddha Tantrayana dari Subkontinen India Utara dan Bali pada abad ke-11 Ambra CALO Department of Archaeology and Natural History, The Australian National University [email protected] Translation by: Christa HARDJASAPUTRA, Alphawood Alumna, Postgraduate Diploma of Asian Art, SOAS University of London Edited by: Ben WREYFORD, Pratu Editorial Team Received 1 April 2019; Accepted 1 November 2019; Published 8 May 2020 Funding statement: The research for this study was funded by the Southeast Asian Art Academic Programme, Academic Support Fund (SAAAP #049), at SOAS University of London. The author declares no known conflict of interest. Abstract: This study examines the significance of the originally Hindu goddess Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā slaying the buffalo demon) in Tantric Buddhist temple contexts of the 8th–11th century in Afghani- stan and northeastern India, and 11th-century Bali. Taking a cross-regional approach, it considers the genesis of Tantric Buddhism, its transmission to Indonesia, and its significance in Bali during the 10th–11th century. Drawing primarily on archaeological and iconographic evidence, it suggests that Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī is likely to have reached Bali as part of a late 10th–11th century phase of renewed transmission of Tantric Buddhism from the northeastern Indian subcontinent to Indonesia, following an initial late 7th–8th century phase. Keywords: Bali, Durgā, Heruka, Mahiṣāsuramardinī, maritime networks, Padang Lawas, Tantric Buddhism, Tantric Śaivism, Tapa Sardār, Uḍḍiyāna, Vajrayāna, Vikramaśīla, Warmadewa Abstrak: Penelitian ini melihat signifikansi dari dewi Hindu Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī (Durgā membunuh iblis kerbau) dalam konteks kuil Buddha Tantrayana pada abad ke-8 hingga ke-11 di Afghanistan dan timur laut India, serta abad ke-11 di Bali. -

Religion in Bali by C. Hooykaas

Religion in Bali by C. Hooykaas Contents Acknowledgments Bibliography 1. Orientation 2. First Acquaintance 3. Kanda Mpat 4. Some Dangers 5. Impurity 6. Demons 7. Black Magic 8. Holy Water(s) 9. Priests: Pamangku 10. Priests: Padanda 11. Priests: Amangku Dalang 12. Priests: Sengguhu 13. Priests: Balian 14. Priests: Dukuh 15. Trance 16. Laymen 17. Humble Things 18. Rites de Passage 19. Burial and Cremation 20. The Playful Mind 21. Cows Not Holy 22. Legends to the Illustrations 23. Plates at the end of the book Acknowledgements First of all I thank my wife who from the outset encouraged me and advised me. In the field of photography I received help from: Drs. P. L. Dronkers, Eindhoven: a, b 1. Prof. Dr. J. Ensink, University of Groningen: n 1, n 2. Mrs. Drs. Hedi Hinzler, Kern Institute, Leiden. d 2, m 2, u 1 5, w 1, w 2, x 2, x 3. Mr. Mark Hobart, M. A. University of London: k 1, k 4, o 4, o 5. Mrs. Drs. C. M. C. Hooykaas van Leeuwen Boomkamp: g 3, k 2, k 3, m 3, o 1, o 2, p 1 3, q 1 5, t 2, t 5, v 1 4, w 3 4, x 1, x 4. Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal , Land en Volkenkunde, Leiden: f 1. (Gedong) Kirtya, Singaraja, Bali, Indonesia: c 1 3, z 1 (original drawings). Library of the University, Leiden: h 1 6, i 1 7, j 1 8. Museum voor Volkenkunde, Delft: d 3, d 4. Rijks Museum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden: f 2, r 1, y 2. -

The Byar: an Ethnographic and Empirical Study of a Balinese Musical Moment

The Byar: An Ethnographic and Empirical Study of a Balinese Musical Moment Andy McGraw with Christine Kohnen INTRODUCTION HE repertoire of the Balinese gamelan gong kebyar ensemble (see Tenzer 2000 and the T glossary provided in Appendix A) is marked by virtuosic, unmetered tutti passages, referred to as kebyar, that often introduce pieces or function as transitions within compositions. The kebyar itself often begins with a sudden, fortissimo byar, a single, tutti chord that is performed by the majority of the ensemble.1 The sheer virtuosity and power of this famous repertoire is encapsulated in the expert execution of a byar, in which twenty to thirty musicians, without the aid of notation, a conductor, or beat entrainment, synchronize to produce a shockingly precise and loud eruption of sound. During several fieldwork sessions in Bali over the past decade, McGraw has occasionally heard expert performers and composers claim that they could identify regional ensembles simply by hearing them perform a single byar. Several informants suggested that the relative temporal alignment of instrumental onsets was the primary distinguishing characteristic of a byar. This would be the equivalent to being able to identify symphony orchestras by hearing, for example, only the first sforzando chord of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. This paper concerns the expression and recognition of group identity as conveyed through performance and listening. Is the temporal structuring of an ensemble’s byar indicative of their musical identity? What is the minimal temporal scale of the expression of such identity? If such differences are not empirically evident or statistically significant, what implications does this have for Balinese conceptions of musical identity? What does this approach reveal about Balinese and non-Balinese listening habits and abilities and how they overlap or diverge? Because these questions are extremely complex we have limited our investigation to the smallest building block of the kebyar repertoire: the musical moment of the byar. -

Diversity of Cultural Elements at the Reliefs of Pura Desa Lan Puseh in Sudaji Village, Northern Bali

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 197 5th Bandung Creative Movement International Conference on Creative Industries 2018 (5th BCM 2018) Diversity of Cultural Elements at The Reliefs of Pura Desa Lan Puseh in Sudaji Village, Northern Bali I Dewa Alit Dwija Putra1*, Sarena Abdullah2 1School of Creative Industries-Telkom University, Indonesia 2School of Arts, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Malaysia Abstract. Northern Bali as a coastal region is the path of global trade traffic from the beginning of the Christian Calendar so that the relations of Balinese people with the outside world are so intense and have an impact on the socio-cultural changes of the society, especially the of ornament art. Ornaments applied to temple buildings in Bali are the result of classical Hindu culture, but in the reliefs of the temple of Desa Lan Puseh in the village of Sudaji, North Bali describes multicultural cultures such as Hinduism, Buddhism, China, as well as Persia as well as elements of European culture. The formation of these ornaments is certainly through a long process involving external and internal factors. The process of dialogue and acculturation of foreign cultures towards local culture gives change and forms new idioms that leave their original forms, as well as new functions, symbols, and meanings in Balinese society. This research uses the socio-historical qualitative method to write chronologically the inclusion of the influences of foreign cultural elements on Balinese social life with visual analysis through the stages to be able to describe and reveal the transformation of relief forms in the temple. This paper also proves that elements of foreign culture such as Islam and European had enriched the ornamental arts of Balinese tradition. -

Church Architecture and Its Impact on Balinese Identity and Tourism

Journal of Heritage Tourism ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjht20 Designing for authenticity: the rise of ‘Bathic’ church architecture and its impact on Balinese identity and tourism Keith Kay Hin Tan & Camelia Kusumo To cite this article: Keith Kay Hin Tan & Camelia Kusumo (2020): Designing for authenticity: the rise of ‘Bathic’ church architecture and its impact on Balinese identity and tourism, Journal of Heritage Tourism, DOI: 10.1080/1743873X.2020.1798971 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1798971 Published online: 27 Jul 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjht20 JOURNAL OF HERITAGE TOURISM https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2020.1798971 Designing for authenticity: the rise of ‘Bathic’ church architecture and its impact on Balinese identity and tourism Keith Kay Hin Tan and Camelia Kusumo School of Architecture, Building and Design, Faculty of Innovation and Technology, Taylor’s University, Subang Jaya, Malaysia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Whereas the architecture of churches throughout most of Southeast Asia is Received 18 February 2020 typified by colonial or neocolonial typologies, the design of Catholic Accepted 16 July 2020 churches in Bali, especially since the 1970s, has been undergoing a KEYWORDS profound localization. The brainchild of Indonesian architects, these Balinese churches; Bathic churches combine the use of traditional and modern techniques with architecture; authenticity; the labour of craftsmen who have for generations worked on the Hindu identity; touristic potential temples most tourists perceive as authentically Balinese. -

Temples, Terraces, and Rice Farmers of Bali Dr

The Blind Spot in the Green Revolution: Temples, Terraces, and Rice Farmers of Bali Dr. Cynthia A. Wei, Dr. William Burnside, and Dr. Judy Che-Castaldo National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center Balinese rice terraces (Wikipedia.org) rice terrace(commons.wikimedia.org) Balinese water temple (Wikipedia.org) Authors’ note: We are interested in improving this case and in tracking its use. We welcome any comments on the use of this case, suggestions to improve it, and basic information about how it was used. Please contact Dr. Cynthia Wei at [email protected]. Thank you in advance! Summary This case explores the complex interactions in a socio-environmental system, the Balinese wet rice cultivation system. Using a combination of the interrupted case and directed case methods, students are presented with an issue that arose during the implementation of Green Revolution agricultural policies in Bali: rice farmers were required to plant new high yield rice varieties continuously rather than following the coordinated cropping schedules set up by water temple priests. Students examine qualitative and quantitative data from classic anthropological research by Dr. Stephen Lansing to learn about the important role that water temples play in achieving sustainable rice cultivation in Bali. Using a model that synthesizes ecological, hydrological, and ethnographic data, Lansing and his colleague, Dr. James Kremer, were able to demonstrate that temple priests determine the cropping schedules for farmers in a way that reduces pest growth and helps to manage limited water resources, maximizing rice yields. This four-part case can be used for a wide range of courses in a few class periods (total class time approximately 4.5-5 hrs.) The Blind Spot in the Green Revolution by Drs. -

The Temple of Besakih, Sukuh, and Cetho: the Dynamics of Cultural Heritage in the Context of Sustainable Tourism Development in Bali and Java

http://wjss.sciedupress.com World Journal of Social Science Vol. 6, No. 1; 2019 The Temple of Besakih, Sukuh, and Cetho: The Dynamics of Cultural Heritage in the Context of Sustainable Tourism Development in Bali and Java I Ketut Ardhana1,*, I Ketut Setiawan1 & Sulanjari1 1Faculty of Art, Universitas Udayana, Denpasar, Indonesia *Correspondence: Faculty of Art, Universitas Udayana, Denpasar, Indonesia. Tel: 62-812-3864-9192. E-mail: [email protected] Received: January 2, 2019 Accepted: January 14, 2019 Online Published: January 22, 2019 doi:10.5430/wjss.v6n1p26 URL: https://doi.org/10.5430/wjss.v6n1p26 Abstract Besakih is one of the biggest Hindu temple in Bali and the temple of Sukuh and Cetho are the Hindu temple that still existing in Central Java. These temples have their similarity and differences in the context of how to develop the sustainable tourist development in Indonesia. However, there are not many experts who understand about the cultural relation between the temple of Besakih in Bali, Sukuh and Cetho in Central Java. This becomes important since the indigenization process that took place in the past of history in the two islands are significant to be understood in terms of social cultural, economic and political development in which their influences can be seen at the modern and postmodern Balinese culture. The development of Balinese temple of Besakih can be considered in the 11th century, while for Sukuh and Cetho temple after the fall of Majapahit kingdom in the 15th century. Therefore, it can be said that Hindu did not only develop in Bali, but also in Central Java, in which the development of Hindu for the beginning already took place indeed in the 7th to 8th in the context of Hindu Mataram namely in the era of king Sanjaya. -

Guide to Bali Prayer

BEGINNERS GUIDE TO BALINESE PRAYER, OFFERINGS, TEMPLES AND RELIGIOUS CEREMONIES by Jim Cramer © www.baliadvisor.com 1 Guide to Balinese Prayer This short introduction will hopefully serve as a guide to help visitors understand the essence of Balinese Religious Prayer and explain the do’s and don’ts while observing or participating in them. The Balinese feel themselves to be a blessed people; a feeling continually reinforced by the wealth of their every-day life and strengthened by the splendor of their religion. The beliefs of the Balinese are a living force that pervades the island and reverberates outside it. The island sings of love. The love that spends an hour making an offering of woven palm leaves and beautiful flowers. The love that finds the time, everyday, to think of giving something to the Gods; by lighting a stick of incense, by praying a Mantra, by sprinkling holy water or by doing a Mudra (a sacred movement with the hands). Bali is also the love bestowed upon their children, the beautiful processions and the intricate offerings made with simple humility. The Balinese consider magic as true and the power of spirits and much of their religion is grounded in this belief .As in Hinduism, Balinese religion is a quest for balance between the forces of good and evil. The main expression of Balinese religion is through rituals or festivals in which the people spend hours making offerings of flowers, food, and palm leaf Figures. Daily small offerings called “canang sari”, which contain symbolic food and flowers are placed in temples and shrines around the family compound. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 02:04:41PM Via Free Access Plate 7.1

Chapter VII Candi Panataran: Panji, introducing the pilgrim into the Tantric doctrine Candi Panataran, considered to be the State Temple of Majapahit and dedicated to the worship of Siwa, is the largest temple complex in East Java. Its significance in Majapahit religious practices and politics was continuously developed throughout the building activities in the temple during the fourteenth and beginning of fifteenth century. Narrative re- liefs with cap-figures are scattered over several buildings: in two bathing places and in all of the three courtyards of the temple complex. Candi Panataran provides the largest number of depictions of cap-figures in comparison to other East Javanese temples. layout and architecture Candi Panataran lies about 12 kilometres to the northeast of the town of Blitar on the lower slopes of the active volcano Mount Kelud.1 It is a temple complex with an oblong layout consisting of three courts stretch- ing from west to east. The ground levels of the three courtyards slope gently upwards from west to east, the axis of the whole complex being oriented towards the east. Mount Kelud, whose peak (1730 metres) lies at a distance of about 15 kilometres from Panataran to the north-north- east, is visible on clear days; the temple axis is, however, not oriented towards this mountain. It is possible that Candi Panataran’s orientation is directed towards Mount Semeru (3676 metres), the highest mountain 1 Mount Kelud erupted eight times during the Majapahit period (Sartono and Bandono 1995:43-53). During the last centuries, this volcano was again active and erupted frequently with different measures of destructiveness. -

Hanuman, the Flying Monkey E Symbolism of the Rāmāyaṇa Reliefs at the Main Temple of Caṇḍi Panataran

Hanuman, the Flying Monkey e symbolism of the Rāmāyaṇa Reliefs at the Main Temple of Caṇḍi Panataran Lydia Kieven Introduction: Caṇḍi Panataran and the Rāmāyaṇa reliefs is paper investigates the relief depictions of the KR on the walls of the Main Temple of Caṇḍi Panataran in East Java. e selection of the episodes and scenes of the narrative and the spatial arrangement of the depictions was in- tended to convey a specific symbolic meaning. e visual medium allowed this to deviate from the literary text and put the focus on a specific topic: on Hanuman’s mystic and magic power śakti in the confrontation with the world destroyer Rāwaṇa. I argue that the reliefs form part of a Tantric concept which underlies the symbolism of the whole temple complex, and that within this theme Hanuman plays a role as an intermediary. e paper continues Stut- terheim’s (, ) analysis of the Rāmāyaṇa reliefs, Klokke’s study () on Hanuman’s outstanding role in the art of the East Javanese period, and my own recent investigation of the Pañji stories at Caṇḍi Panataran (Kieven , particularly pp. –). e Rāmāyaṇa reliefs on the walls of the lower terrace of the Main Tem- ple of Caṇḍi Panataran are known as the major East Javanese pendant to the Central Javanese Rāmāyaṇa reliefs at Caṇḍi Loro Jonggrang. e description of the two relief series, their identification, and their comparison are the major concern of Stutterheim’s German monograph, made more generally ac- cessible in English translation as Rāma legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia in . rough his description of the panels at Caṇḍi Panataran he proved convincingly that the KR is the underlying narrative.