Stephen Lansing, 1991, PRIESTS and PROGRAMMERS, Princeton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOMA THEATRE OFFERS Will Be Spent in Recreational Activi- Time During These Hours

Cnlottta Courier VOL. 43 COLOMA, MICHIGAN. FRIDAY, JUNE 20, 1941. NO. 46 State C. E. Union to Camp Madron Will Auto Wreck Fatal to Berrien County Weddings Paul Hull Writes on Michigan's Largest Grows in Van Buren County Miss Victoria Hattie Skorupa, Meet in Benton Harbor Open Next Sunday Mrs. Geo. Sattler daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Thomas America First Move Skorupa of Baroda, and Harry Vin- cent Hackel, Jr., son of Mrs. C. R. Fitzcharles of Benton Harbor, were 1,500 Delegates Expected to Attend Many Improvements Have Been Wife of Former Drain Commission- united in wedlock at St. Agnes' Editor, The Coloma Courier: m With reference to the Chapter of Annual Convention Next Week— Made at Grounds and Record Sea- er Killed in Wyoming—Husband church in Sawyer on June 14, 1941, A wedding dinner was served at the the America First Committee or- All Sessions to be Held at Peace son Is Anticipated. and Daughter Were Both Injured. home of the bride's parents, and a ganized In Coloma, I am for Amer- reception was held later at the ica first, too. Since discussions are Temple. Sunday afternoon, June 22, Camp Mrs. George Sattler, wife of a American Legion hall in Baroda. called for, I believe I can set forth Madron will open its sixteenth sea- former drain commissioner of Ber- my views more briefly and lucidly The 53rd annual convention of son. According to announc»,ffient rien county, was instantly killed in in writing and hope for the privi- the Michigan Christian Endeavor made by Scout Executive Oscar an automobile wreck near Buffaflo, Miss Theresa Menchinger, daugh- lege of having them published In Union will convene in Benton Har- Noll, the attendance records of prg- Wyoming, on Wednesday of last ter of Mr. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN . 1.1 Latar Belakang Indonesia Terkenal

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN . 1.1 Latar Belakang Indonesia terkenal dengan beragam adat, kebudayaan, suku, agama, maupun kepercayaan yang dianut. Salah satu pulau di Indonesia yang sangat disegani yakni Pulau Bali. Pulau Bali dikenal dengan julukan “Pulau Beribu Pura”. Pulau yang memiliki luas 5.780 km2, memiliki pura yang tersebar disegala penjuru. Bahkan pada setiap jengkal tanah di Bali dapat kita jumpai pura, baik yang terdapat disetiap rumah masyarakat Hindu maupun disetiap sudut daerah atau desa di Bali. Dalam ajaran Agama Hindu terdapat pembagian pura yang digolongkan berdasarkan klasifikasi tertentu. Pada setiap desa terdapat tiga pura utama yang disebut sebagai Pura Khayangan Tiga, kemudian dalam lingkup yang lebih besar ada Pura yang tergolong Pura Sad Khayangan Jagat yang terdiri atas enam pura utama, kemudian pura yang termasuk kedalam Pura Khayangan Jagat yang terdiri dari sembilan pura penguasa arah mata angin. Kemudian Pura Dhang Khayangan yang didirikan oleh tokoh penting keagamaan pada zaman kejayaan Hindu di Bali. Pura Dhang Kahyangan dijadikan tempat penghormatan atas jasa yang dilakukan oleh tokoh tersebut, yang diyakini telah membantu masyarakat daerah Bali Kuno dalam menyelesaikan masalah mereka. 1 2 Salah satu yang temasuk tiga pura terbesar di Bali selain Pura Besakih di Kabupaten Karangasem dan Pura Ulun Danu Batur di Kabupaten Bangli yakni Pura Sad Kahyangan Lempuyang Luhur di Kabupaten Karangasem. Pura Sad Kahyangan Lempuyang Luhur memiliki peran yang sangat penting bagi Umat Hindu di Bali. Peran Pura Sad Kahyangan Lempuyang Luhur diantaranya sebagai Catur Loka Pala, Padma Bhuwana dan juga Dewata Nawa Sanga atau Pura Sad Khayangan Jagat. Terletak di atas Bukit Lempuyang yang termasuk kedalam daerah Desa Adat Purwaayu, Desa Dinas Tribuana, Kecamatan Abang, Kabupaten Karangasem, Bali. -

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province (Indonesia) No 1194Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Fund for preparing the Nomination Cultural Landscape of Bali Province 30 June 2001 (Indonesia) Date received by the World Heritage Centre No 1194rev 31 January 2007 28 January 2011 Background This is a deferred nomination (32 COM, Quebec City, Official name as proposed by the State Party 2008). The Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana The World Heritage Committee adopted the following Philosophy decision (Decision 32 COM 8B.22): Location The World Heritage Committee, Province of Bali 1. Having examined Documents WHC-08/32.COM/8B Indonesia and WHC-08/32.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Defers the examination of the nomination of the Brief description Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, Indonesia, to the Five sites of rice terraces and associated water temples World Heritage List in order to allow the State Party to: on the island of Bali represent the subak system, a a) reconsider the choice of sites to allow a unique social and religious democratic institution of self- nomination on the cultural landscape of Bali that governing associations of farmers who share reflects the extent and scope of the subak system of responsibility for the just and efficient use of irrigation water management and the profound effect it has water needed to cultivate terraced paddy rice fields. had on the cultural landscape and political, social and agricultural systems of land management over at The success of the thousand year old subak system, least a millennia; based on weirs to divert water from rivers flowing from b) consider re-nominating a site or sites that display volcanic lakes through irrigation tunnels onto rice the close link between rice terraces, water temples, terraces carved out of the flanks of mountains, has villages and forest catchment areas and where the created a landscape perceived to be of great beauty and traditional subak system is still functioning in its one that is ecologically sustainable. -

Patents Office Journal

PATENTS OFFICE JOURNAL IRISLEABHAR OIFIG NA bPAITINNÍ Iml. 87 Cill Chainnigh 01 February 2012 Uimh. 2195 CLÁR INNSTE Cuid I Cuid II Paitinní Trádmharcanna Leath Leath Official Notice 379 Official Notice 159 Applications for Patents 381 Applications for Trade Marks 161 Applications Published 382 Trade Mark Re-Advertised 174 Patents Granted 383 Oppositions under Section 43 174 European Patents Granted 384 Application(s) Amended 174 Applications Withdrawn, Deemed Withdrawn or Application(s) Withdrawn 179 Refused 445 Trade Marks Registered 179 Applications Lapsed 446 Trade Marks Renewed 180 Patents Lapsed 446 Unpaid Renewal Fees 182 Request for Grant of Supplementary Protection Trade Marks Removed 189 Certificate 560 Leave to Alter Registered Trade Mark(s) Patents Expired 561 Granted 193 Short Term Patent Deemed Void 563 International Registrations under the Madrid European Patents Always Void 564 Protocol 193 Application for Restoration of Patents under International Trade Marks Protected 219 Section 30 of the Patents (Amendment) Act 2006 578 Cancellations effected under the Madrid Protocol 220 Errata 222 Dearachtaí Designs Information under the 1927 Act Designs Extended 578 Designs Information under the 2001 Act Designs Renewed 578 Design Rights Expired 578 The Patents Office Journal is published fortnightly by the Irish Patents Office. Each issue is freely available to view or download from our website at www.patentsoffice.ie © Government of Ireland, 2012 © Rialtas na hÉireann, 2012 (01/02/2012) Patents Office Journal (No. 2195) 379 Patents Office Journal Irisleabhar Oifig Na bPaitinní Cuid I Paitinní agus Dearachtaí No. 2195 Wednesday, 1 February, 2012 NOTE: The office does not guarantee the accuracy of its publications nor undertake any responsibility for errors or omissions or their consequences. -

R. Tan the Domestic Architecture of South Bali In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 123 (1967), No: 4, Leiden, 442-4

R. Tan The domestic architecture of South Bali In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 123 (1967), no: 4, Leiden, 442-475 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/01/2021 05:53:05PM via free access THE DOMESTIC ARCHITECTURE OF SOUTH BALI* outh Bali is the traditional term indicating the region south of of the mountain range which extends East-West across the Sisland. In Balinese this area is called "Bali-tengah", maning centra1 Bali. In a cultural sense, therefore, this area could almost be considered Bali proper. West Lombok, as part of Karangasem, see.ms nearer to this central area than the Eastern section of Jembrana. The narrow strip along the Northern shoreline is called "Den-bukit", over the mountains, similar to what "transmontane" mant tol the Romans. In iwlated pockets in the mwntainous districts dong the borders of North and South Bali live the Bali Aga, indigenous Balinese who are not "wong Majapahit", that is, descendants frcm the great East Javanece empire as a good Balinese claims to be.1 Together with the inhabitants of the island of Nusa Penida, the Bali Aga people constitute an older ethnic group. Aernoudt Lintgensz, rthe first Westemer to write on Bali, made some interesting observations on the dwellings which he visited in 1597. Yet in the abundance of publications that has since followed, domstic achitecture, i.e. the dwellings d Bali, is but slawly gaining the interest of scholars. Perhaps ,this is because domestic architecture is overshadowed by the exquisite ternples. -

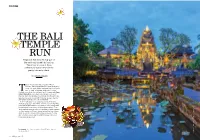

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession. -

I LAMBANG ORNAMEN LANGIT

LAMBANG ORNAMEN LANGIT - LANGIT RUANG KWAN TEE KOEN KLENTENG KWAN TEE KIONG YOGYAKARTA DITINJAU DARI FILSAFAT CHINA SKRIPSI Diajukan kepada Fakultas Bahasa dan Seni Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Persyaratan guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan oleh Nanda Harya Hellavikarany NIM. 11206241003 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SENI RUPA FAKULTAS BAHASA DAN SENI UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA OKTOBER 2015 i MOTTO Segala sesuatu yang terbentuk, kelak akan terurai. Segala sesuatu berawal dari kosong, dan kembali kosong. Kehidupan bagaikan roda yang terus - menerus berputar tanpa henti. Setiap sesuatu mengalami dua jalan tersebut (terbentuk dan terurai; terbentuk dan terurai; terbentuk dan terurai; begitu seterusnya), tiada jalan lain. Oleh karenanya, kehidupan diwarnai dengan yin dan yang. Keseluruhan Alam Semesta adalah satu mekanisme. Jika salah satu bagian darinya keluar dari aturan, maka bagian lainnya juga akan keluar dari aturan. Segala sesuatu cenderung menarik sesuatu yang sejenis dengannya. Oleh karenanya, jika salah satu berjalan sesuai kebenaran, maka keseluruhan yang lain juga akan berjalan sesuai kebenaran. Pembalikan adalah ketetapan hukum alam. Ketika sesuatu telah mencapai titik ekstrem, maka cenderung akan berbalik darinya. Segala sesuatu memiliki batasan kekuatan, seperti bola yang dilambungkan ke atas, setelah ia mencapai titik tertingginya, maka bola akan kembali ke tempat semulanya (jatuh). Oleh karenanya, segala sesuatu harus hidup sewajarnya, mengambil jalan tengah, jangan terlalu sedikit dan terlalu banyak (jangan mengambil langkah ekstrem). v PERSEMBAHAN Alhamdulillahirobbil „alamin. Ridho-Mu senantiasa menyertaiku. Sebuah langkah usai sudah. Satu cita telah ada di tanganku. Namun… Itu bukanlah akhir dari perjalanan. Melainkan awal dari satu perjuangan. Hari takkan indah tanpa mentari dan rembulan. Begitu juga hidup takkan indah tanpa tujuan / harapan dan tantangan. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 28 1st International Conference on Tourism Gastronomy and Tourist Destination (ICTGTD 2016) SWOT Analysis for Cultural Sustainable Tourism at Denpasar City Case Study: SWOT Analysis in Puri Agung Jro Kuta A.A. Ayu Arun Suwi Arianty DIII Hospitality , International Bali Institute of Tourism Denpasar, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Puri Agung Jro Kuta is one cultural tourist Bali is a small island part of Indonesia, an archipelagic destination in Denpasar, Bali which is not yet explored. Denpasar country in Southeast Asia. It has a blend of Balinese Hindu/ as a capital city of Bali is very famous with Sanur Beach, but only Buddhist religion and Balinese custom, which make a rich and a few tourists know about Puri Agung Jro Kuta as a cultural diverse cultures. Bali divided into eight regencies and one city, tourist destination. The aim of this research is to identify the they are Badung Regency, Bangli Regency, Buleleng Regency, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of Puri Agung Gianyar Regency, Jembrana Regency, Karangasem Regency, Jro Kuta as a cultural tourist destination in Denpasar. Klungkung Regency, Tabanan Regency, and Denpasar City Furthermore, this research will be used for tourism planning by (Wikipedia Bali.2016). listing the advantages and challenges in the process. In attempt to diagnose the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of The cultural tourism in Bali arise since 1936, where Walter Puri Agung Jro Kuta, in the current status and potential, this Spies, Rudolf Bonnet ( Dutch Painter who came to Bali in research conducted a SWOT analysis on this tourism sector. -

GROY Groenewegen, JM (Johannes Martinus / Han)

Nummer Toegang: GROY Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / Archief Het Nieuwe Instituut (c) 2000 This finding aid is written in Dutch. 2 Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / GROY Archief GROY Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / 3 Archief INHOUDSOPGAVE BESCHRIJVING VAN HET ARCHIEF......................................................................5 Aanwijzingen voor de gebruiker.......................................................................6 Citeerinstructie............................................................................................6 Openbaarheidsbeperkingen.........................................................................6 Archiefvorming.................................................................................................7 Geschiedenis van de archiefvormer.............................................................7 Groenewegen, Johannes Martinus............................................................7 BESCHRIJVING VAN DE SERIES EN ARCHIEFBESTANDDELEN........................................13 GROY.110659917 supplement........................................................................63 BIJLAGEN............................................................................................. 65 GROY Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / 5 Archief Beschrijving van het archief Beschrijving van het archief Naam archiefblok: Groenewegen, J.M. (Johannes Martinus / Han) / Archief Periode: 1948-1970, (1888-1980) Archiefbloknummer: GROY Omvang: 1,86 meter Archiefbewaarplaats: -

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer L. Goodlander August 2010 © 2010 Jennifer L. Goodlander. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali by JENNIFER L. GOODLANDER has been approved for the Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Theater Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GOODLANDER, JENNIFER L., Ph.D., August 2010, Interdisciplinary Arts Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali (248 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee The role of women in Bali must be understood in relationship to tradition, because “tradition” is an important concept for analyzing Balinese culture, social hierarchy, religious expression, and politics. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is considered an important Balinese tradition because it connects a mythic past to a political present through public, and often religiously significant ritual performance. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and priest. Until recently, the dalang has always been male, but now women are studying and performing as dalangs. In order to determine what women in these “non-traditional” roles means for gender hierarchy and the status of these arts as “traditional,” I argue that “tradition” must be understood in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a “traditional” society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by “tradition,” and the performing arts as both “traditional” and as a conduit for “tradition.” This dissertation is divided into three sections, beginning in chapters two and three, with a general focus on the “tradition” of wayang kulit through an analysis of the objects and practices of performance. -

Bangli Explore 2021

BANGLI EXPLORE 2021 Bangli Explore 2020 I Gede Sutarya Pariwisata Agama, Budaya dan Spiritual e-ISSN 2684-964X i I Gede Sutarya Bangli Explore 2021 Mempromosikan budaya, agama dan spiritual Kabupaten Bangli, sebagai destinasi pariwisata Persembahan untuk Bangli Yayasan Wikarman 2021 ii Bangli Explore 2021 Sutarya, I Gede Lay out: I Nyoman Jati Karmawan Sutarya, I Gede Bangli Explore Layout: I Nyoman Jati Karmawan Yayasan Wikarman Bangli 2020 VI+39 Halaman; e-ISSN 2684-964X 1. Pariwisata 3. Kebudayaan 2. Agama 4. Spiritual Penerbit Yayasan Wikarman Toko Ditu, Jalan Tirta Geduh, LC Subak Aya, Bangli, Bali 80613 Telp (Hp) +6281997852219 Email: [email protected] Percetakan: Bhakti Printing, Jl Singasari Utara, Gang Umapunggul, Denpasar Hak Cipta Dilindungi Undang-Undang iii Kata Pengantar Om Swastyastu, Puja bhakti, kami panjatkan kepada Ida Sanghyang Widhi, karena Bangli Explore 2021 bisa terbit. Bangli Explore 2021 ini merupakan lanjutan dari Bangli Explore 2020 dan 2019. Karena itu, pada tahun ini, Bangli Explore telah terbit tiga kali. Hal ini merupakan kebanggaan bagi kami, yang ingin terus berkiprah dan berkontribusi dalam pembangunan Bangli, melalui promosi pariwisata. Kami mengucapkan terima kasih kepada Saudara I Gede Sutarya, yang telah menulis Bangli Explore 2021 ini. Kami juga berterima kasih kepada berbagai pihak yang telah membantu melengkapi data- data dalam buku ini, seperti Bapak I Ketut Kayana, yang merupakan Bendesa Majelis Desa Adat Kabupaten Bangli. Terima kasih juga untuk Bapak I Nyoman Sukra, yang merupakan Ketua Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia (PHDI) Kabupaten Bangli atas berbagai masukannya. Kami juga mengucapkan terima kasih kepada Bupati Bangli, I Made Gianyar, yang juga telah memberikan berbagai fasilitas untuk melengkapi data-data buku ini. -

Kondisi Pura Dalem Bias Muntig Dari Tahun Ketahun Mengalami

MASTER PLAN PENATAAN DAN PENGEMBANGAN PURA DALEM BIAS MUNTIG DI DESA PAKRAMAN NYUH KUKUH, DUSUN PED, DESA PED, KECAMATAN NUSA PENIDA, KLUNGKUNG I Kadek Merta Wijaya Dosen Program Studi Teknik Arsitektur, Fakultas Teknik, Universitas Warmadewa e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRAK Kondisi Pura Dalem Bias Muntig dari tahun ketahun mengalami penurunan kualitas fisik dan seiring dengan itu juga, status sebagai Pura Kahyangan Jagad di Nusa Penida semakin tersebar sampai di luar Pulau Nusa Penida. Hal tersebut menuntut adanya pembenahan dan penataan yang lebih baik. Berdasarkan wawancara dengan tokoh masyarakat setempat menyebutkan bahwa diperlukan suatu: (1) penataan dan pengembangkan Pura Dalem; (2) penambahan dua bangunan pelinggih di dalam area Pura Bias Muntig; (3) perencanaan pesraman pemangku; (4) penataan lanskap atau ruang luar seperti tempat parkir, fasilitas MCK dan penataan jalur pedestrian pemedek; serta (5) penataan area tempat melasti. Pengabdian ini bertujuan untuk menyusun rancangan kembali (redesign) Pura Dalem Bias Muntig dalam menjawab permasalahan-permasalahan yang sedang dihadapi oleh masyarakat setempat baik permasalahan keruangan maupun manajemen pembangunannya. Aspek keruangannya yaitu sebagai dasar acuan dalam penataan dan pengembangan kedepannya sedangkan aspek manajemen pembangunan yaitu sebagai dasar dalam mengajukan proposal pendanaan kepada pemerintah maupun swasta. Sasaran dan manfaat kegiatan pengabdian ini mengarah kepada tiga pihak yaitu masyarakat Desa Pakraman Nyuh Kukuh, masyarakat umum dan institusi Universitas Warmadewa sebagai lembaga dalam pengembangan Tri Dharma Perguruan Tinggi yaitu pengabdian kepada masyarakat. Metode kegiatannya yaitu menggali informasi-informasi di masyarakat melalui tokoh-tokoh masyarakat sebagai mitra dialog tentang permasalahan-permasalahan yang sedang dihadapi yaitu penataan dan pengembangan Pura Dalem Bias Muntig, yang selanjutnya diselesaikan melalui solusi-solusi dengan mempertimbangkan keinginan dan kepentingan masyarakat setempat.