Durgā Mahiṣāsuramardinī in Likely Tantric Buddhist Context from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concise Ancient History of Indonesia.Pdf

CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY OF INDONESIA CONCISE ANCIENT HISTORY O F INDONESIA BY SATYAWATI SULEIMAN THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL FOUNDATION JAKARTA Copyright by The Archaeological Foundation ]or The National Archaeological Institute 1974 Sponsored by The Ford Foundation Printed by Djambatan — Jakarta Percetakan Endang CONTENTS Preface • • VI I. The Prehistory of Indonesia 1 Early man ; The Foodgathering Stage or Palaeolithic ; The Developed Stage of Foodgathering or Epi-Palaeo- lithic ; The Foodproducing Stage or Neolithic ; The Stage of Craftsmanship or The Early Metal Stage. II. The first contacts with Hinduism and Buddhism 10 III. The first inscriptions 14 IV. Sumatra — The rise of Srivijaya 16 V. Sanjayas and Shailendras 19 VI. Shailendras in Sumatra • •.. 23 VII. Java from 860 A.D. to the 12th century • • 27 VIII. Singhasari • • 30 IX. Majapahit 33 X. The Nusantara : The other islands 38 West Java ; Bali ; Sumatra ; Kalimantan. Bibliography 52 V PREFACE This book is intended to serve as a framework for the ancient history of Indonesia in a concise form. Published for the first time more than a decade ago as a booklet in a modest cyclostyled shape by the Cultural Department of the Indonesian Embassy in India, it has been revised several times in Jakarta in the same form to keep up to date with new discoveries and current theories. Since it seemed to have filled a need felt by foreigners as well as Indonesians to obtain an elementary knowledge of Indonesia's past, it has been thought wise to publish it now in a printed form with the aim to reach a larger public than before. -

Conserving the Past, Mobilizing the Indonesian Future Archaeological Sites, Regime Change and Heritage Politics in Indonesia in the 1950S

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 167, no. 4 (2011), pp. 405-436 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101399 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 MARIEKE BLOEMBERGEN AND MARTIJN EICKHOFF Conserving the past, mobilizing the Indonesian future Archaeological sites, regime change and heritage politics in Indonesia in the 1950s Sites were not my problem1 On 20 December 1953, during a festive ceremony with more than a thousand spectators, and with hundreds of children waving their red and white flags, President Soekarno officially inaugurated the temple of Śiwa, the largest tem- ple of the immense Loro Jonggrang complex at Prambanan, near Yogyakarta. This ninth-century Hindu temple complex, which since 1991 has been listed as a world heritage site, was a professional archaeological reconstruction. The method employed for the reconstruction was anastylosis,2 however, when it came to the roof top, a bit of fantasy was also employed. For a long time the site had been not much more than a pile of stones. But now, to a new 1 The historian Sunario, a former Indonesian ambassador to England, in an interview with Jacques Leclerc on 23-10-1974, quoted in Leclerc 2000:43. 2 Anastylosis, first developed in Greece, proceeds on the principle that reconstruction is only possible with the use of original elements, which by three-dimensional deduction on the site have to be replaced in their original position. The Dutch East Indies’ Archaeological Service – which never employed the term – developed this method in an Asian setting by trial and error (for the first time systematically at Candi Panataran in 1917-1918). -

A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 25 February 2010 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak Addendum Summary of information, including individual cases, transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11514 A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 Contents Paragraphs Page List of abbreviations......................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Summary of allegations transmitted and replies received....................................... 1–305 7 Algeria ............................................................................................................ 1 7 Angola ............................................................................................................ 2 7 Argentina ........................................................................................................ 3 8 Australia......................................................................................................... -

Plataran Borobudur Encounter

PLATARAN BOROBUDUR ENCOUNTER ABOUT THE DESTINATION Plataran Borobudur Resort & Spa is located within the vicinity of ‘Kedu Plain’, also known as Progo River Valley or ‘The Garden of Java’. This fertile volcanic plain that lies between Mount Sumbing and Mount Sundoro to the west, and Mount Merbabu and Mount Merapi to the east has played a significant role in Central Javanese history due to the great number of religious and cultural archaeological sites, including the Borobudur. With an abundance of natural beauty, ranging from volcanoes to rivers, and cultural sites, Plataran Borobudur stands as a perfect base camp for nature, adventure, cultural, and spiritual journey. BOROBUDUR Steps away from the resort, one can witness one the of the world’s largest Buddhist temples - Borobudur. Based on the archeological evidence, Borobudur was constructed in the 9th century and abandoned following the 14th-century decline of Hindu kingdoms in Java and the Javanese conversion to Islam. Worldwide knowledge of its existence was sparked in 1814 by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, then the British ruler of Java, who was advised of its location by native Indonesians. Borobudur has since been preserved through several restorations. The largest restoration project was undertaken between 1975 and 1982 by the Indonesian government and UNESCO, following which the monument was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Borobudur is one of Indonesia’s most iconic tourism destinations, reflecting the country’s rich cultural heritage and majestic history. BOROBUDUR FOLLOWS A remarkable experience that you can only encounter at Plataran Borobudur. Walk along the long corridor of our Patio Restaurants, from Patio Main Joglo to Patio Colonial Restaurant, to experience BOROBUDUR FOLLOWS - where the majestic Borobudur temple follows you at your center wherever you stand along this corridor. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

Cultural Landscape of Bali Province (Indonesia) No 1194Rev

International Assistance from the World Heritage Fund for preparing the Nomination Cultural Landscape of Bali Province 30 June 2001 (Indonesia) Date received by the World Heritage Centre No 1194rev 31 January 2007 28 January 2011 Background This is a deferred nomination (32 COM, Quebec City, Official name as proposed by the State Party 2008). The Cultural Landscape of Bali Province: the Subak System as a Manifestation of the Tri Hita Karana The World Heritage Committee adopted the following Philosophy decision (Decision 32 COM 8B.22): Location The World Heritage Committee, Province of Bali 1. Having examined Documents WHC-08/32.COM/8B Indonesia and WHC-08/32.COM/INF.8B1, 2. Defers the examination of the nomination of the Brief description Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, Indonesia, to the Five sites of rice terraces and associated water temples World Heritage List in order to allow the State Party to: on the island of Bali represent the subak system, a a) reconsider the choice of sites to allow a unique social and religious democratic institution of self- nomination on the cultural landscape of Bali that governing associations of farmers who share reflects the extent and scope of the subak system of responsibility for the just and efficient use of irrigation water management and the profound effect it has water needed to cultivate terraced paddy rice fields. had on the cultural landscape and political, social and agricultural systems of land management over at The success of the thousand year old subak system, least a millennia; based on weirs to divert water from rivers flowing from b) consider re-nominating a site or sites that display volcanic lakes through irrigation tunnels onto rice the close link between rice terraces, water temples, terraces carved out of the flanks of mountains, has villages and forest catchment areas and where the created a landscape perceived to be of great beauty and traditional subak system is still functioning in its one that is ecologically sustainable. -

Challenges in Conserving Bahal Temples of Sri-Wijaya Kingdom, In

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-9, Issue-1, October 2019 Challenges in Conserving Bahal Temples of Sriwijaya Kingdom, in North Sumatra Ari Siswanto, Farida, Ardiansyah, Kristantina Indriastuti Although it has been restored, not all of the temples re- Abstract: The archaeological sites of the Sriwijaya temple in turned to a complete building form because when temples Sumatra is an important part of a long histories of Indonesian were found many were in a state of severe damage. civilization.This article examines the conservation of the Bahal The three brick temple complexes have been enjoyed by temples as cultural heritage buildings that still maintains the authenticity of the form as a sacred building and can be used as a tourists who visit and even tourists can reach the room in the tourism object. The temples are made of bricks which are very body of the temple. The condition of brick temples that are vulnerable to the weather, open environment and visitors so that open in nature raises a number of problems including bricks they can be a threat to the architecture and structure of the tem- becoming worn out quickly, damaged and overgrown with ples. Intervention is still possible if it is related to the structure mold (A. Siswanto, Farida, Ardiansyah, 2017; Mulyati, and material conditions of the temples which have been alarming 2012). The construction of the temple's head or roof appears and predicted to cause damage and durability of the temple. This study used a case study method covering Bahal I, II and III tem- to have cracked the structure because the brick structure ples, all of which are located in North Padang Lawas Regency, does not function as a supporting structure as much as pos- North Sumatra Province through observation, measurement, sible. -

Bělahan and the Division of Airlangga's Realm

ROY E. JORDAAN Bělahan and the division of Airlangga’s realm Introduction While investigating the role of the Śailendra dynasty in early eastern Javanese history, I became interested in exploring what relationship King Airlangga had to this famous dynasty. The present excursion to the royal bathing pla- ce at Bělahan is an art-historical supplement to my inquiries, the findings of which have been published elsewhere (Jordaan 2006a). As this is a visit to a little-known archaeological site, I will first provide some background on the historical connection, and the significance of Bělahan for ongoing research on the Śailendras. The central figure in this historical reconstruction is Airlangga (991-circa 1052 CE), the ruler who managed to unite eastern Java after its disintegration into several petty kingdoms following the death of King Dharmawangśa Těguh and the nobility during the destruction of the eastern Javanese capital in 1006 (Krom 1913). From 1021 to 1037, the name of princess Śrī Sanggrāmawijaya Dharmaprasādottunggadewī (henceforth Sanggrāmawijaya) appears in sev- eral of Airlangga’s edicts as the person holding the prominent position of rakryān mahāmantri i hino (‘First Minister’), second only to the king. Based on the findings of the first part of my research, I maintain that Sanggrāmawijaya was the daughter of the similarly named Śailendra king, Śrī Sanggrāma- wijayottunggavarman, who was the ruler of the kingdom of Śrīvijaya at the time. It seems plausible that the Śailendra princess was given in marriage to Airlangga to cement a political entente between the Śailendras and the Javanese. This conclusion supports an early theory of C.C. -

The Timbul Site, Bali, and the Transformations Project: Material Remains and Considerations of Chronology and Typology

THE TIMBUL SITE, BALI, AND THE TRANSFORMATIONS PROJECT: MATERIAL REMAINS AND CONSIDERATIONS OF CHRONOLOGY AND TYPOLOGY Elisabeth A. Bacus Research Professor, University of Akron Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Timbul site, which a 2000 survey indicated had sig- nificant potential for the study of Bali's early states, was the focus of test excavations as part of the Transfor- mations in the Landscapes of South-Central Bali: An Ar- chaeological Investigation of Early Balinese States. This paper presents results of the analyses of the materials recovered from the 2004 excavations, their chronological information and an earthenware rim shape typology that is also tied to earthenware rim types from dated north coast sites. The excavated deposits, albeit limited, con- tribute further evidence of Bali's Early Metal period and rarely recovered settlement remains from possibly just prior to and during the early Classic period; these re- mains are discussed within the context of current archae- ological knowledge of these periods. INTRODUCTION South-central Bali (Figure 1), particularly the area be- tween the Pakerisan and Petanu rivers, is often considered to have been the center of the island's early states (Bernet Kempers 1991:114-115; Hobart et al. 1996:25). This area has yielded a high concentration of remains (e.g., bronze drums, carved stone sarcophagi) from the early complex societies of the mid/late-1st millennium BC to mid/late-1st millennium AD (Ardika 1987) and from the kingdoms of the Classic Period, particularly of the 11th to mid-14th cen- Figure 1 Location of the Timbul site tury AD. -

The Ultimate Origin of the World, Or the Mula Muh, and Other Mon Beliefs*

THE ULTIMATE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD, OR THE MULA MUH, AND OTHER MON BELIEFS* EMMANUEL GUILLON FORMER CHARGE DE CONFERENCE ECOLE PRATIQUE DES HAUTES ETUDES SECTION DES SCIENCES RELIGEUSES PARIS Can we credit the Mons with possessing a world view, a The first things that came into being were the seasons, hot mental universe, a landscape of feelings and emotions, which and cold. They both appeared at once and were followed by we can deduce from their myths, beliefs and rites, and which a wind that never ceased blowing. The air expanded until it thus is uniquely their own? Since we are by no means deal became an enormous mass. Then the water appeared and ex ing with a human isolate (if indeed such a thing has ever panded also. A mist began to rise up from the water and existed), we will inevitably encounter a network of foreign then fell as rain. The dry season evaporated the water and influences. But such influences often are modified by the the land appeared. The land was able to produce stones and genius of a language and a people. Does there still survive, minerals, and silver, gold, iron, tin and copper soon appeared then, some explanation of the world that can be considered as well as the various precious stones. Then the first kinds of uniquely characteristic of the Mons? vegetation appeared on the gold ore as a kind of moss, fol lowed by grass and all the other plants of the vegetable Mula Muh kingdom. There,does exist, in fact, a cosmology of which we have "The four elements had the propensity to produce living beings. -

Proquest Dissertations

Daoxuan's vision of Jetavana: Imagining a utopian monastery in early Tang Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Tan, Ai-Choo Zhi-Hui Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 09:09:41 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280212 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are In typewriter face, while others may be from any type of connputer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 DAOXUAN'S VISION OF JETAVANA: IMAGINING A UTOPIAN MONASTERY IN EARLY TANG by Zhihui Tan Copyright © Zhihui Tan 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 UMI Number: 3073263 Copyright 2002 by Tan, Zhihui Ai-Choo All rights reserved. -

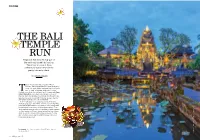

THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali Share the Top Spot on the Must-Visit List with Its Beaches

CULTURE THE BALI TEMPLE RUN Temples in Bali share the top spot on the must-visit list with its beaches. Take a look at some of these architectural marvels that dot the pretty Indonesian island. TEXT ANURAG MALLICK he sun was about to set across the cliffs of Uluwatu, the stony headland that gave the place its name. Our guide, Made, explained that ulu is ‘land’s end’ or ‘head’ in Balinese, while watu is ‘stone’. PerchedT on a rock at the southwest tip of the peninsula, Pura Luhur Uluwatu is a pura segara (sea temple) and one of the nine directional temples of Bali protecting the island. We gaped at the waves crashing 230 ft below, unaware that the real spectacle was about to unfold elsewhere. A short walk led us to an amphitheatre overlooking the dramatic seascape. In the middle, around a sacred lamp, fifty bare-chested performers sat in concentric rings, unperturbed by the hushed conversations of the packed audience. They sat in meditative repose, with cool sandalwood paste smeared on their temples and flowers tucked behind their ears. Sharp at six, chants of cak ke-cak stirred the evening air. For the next one hour, we sat open-mouthed in awe at Bali’s most fascinating temple ritual. Facing page: Pura Taman Saraswati is a beautiful water temple in the heart of Ubud. Elena Ermakova / Shutterstock.com; All illustrations: Shutterstock.com All illustrations: / Shutterstock.com; Elena Ermakova 102 JetWings April 2017 JetWings April 2017 103 CULTURE The Kecak dance, filmed in movies such as There are four main types of temples in Bali – public Samsara and Tarsem Singh’s The Fall, was an temples, village temples, family temples for ancestor worship, animated retelling of the popular Hindu epic and functional temples based on profession.