Prensa AEPSAD 19 Mar 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organizational Forms in Professional Cycling – Efficiency Issues of the UCI Pro Tour

Organizational Forms in Professional Cycling – Efficiency Issues of the UCI Pro Tour Luca Rebeggiani§ * Davide Tondani DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 345 First Version: August 2006 This Version: July 2007 ISSN: 0949–9962 ABSTRACT: This paper gives a first economic approach to pro cycling and analyses the changes induced by the newly introduced UCI Pro Tour on the racing teams’ behaviour. We develop an oligopolistic model starting from the well known Cournot framework to analyse if the actual setting of the UCI Pro Tour leads to a partially unmeant behaviour of the racing teams. In particular, we show that the blamed regional concentration of their race participation depends on a lack of incentives stemming from the licence assignation procedure. Our theo- retical results are supported by empirical data concerning the performance of the racing teams in 2005 and 2006. As a recommendation for future improvements, we derive from the model the need for a relegation system for racing teams. ZUSAMMENFASSUNG: Der Aufsatz stellt die erste ökonomische Analyse des professionellen Radsports dar. Er analysiert insbesondere die Anreizwirkungen der neuen UCI Pro Tour auf Teams und Fahrer. Ausgehend von dem bekannten Cournot-Ansatz entwickeln wir ein einfaches Oligopol-Modell, um zu untersuchen, ob die der- zeitige Pro Tour-Organisation zu einem unerwünschten Verhalten der Teilnehmer führt. Wir zeigen, dass insbe- sondere das Problem der geographischen Konzentration der Rennteilnahmen der Teams von den mangelnden Anreizen abhängt, die vom jetzigen Lizenzvergabesystem ausgehen. Unsere theoretischen Ergebnisse werden durch empirische Daten aus der Pro Tour 2005 und 2006 gestützt. Als Empfehlung für zukünftige Entwicklun- gen leiten wir aus dem Modell die Notwendigkeit einer Öffnung der Pro Tour ab, mit Auf- und Abstiegsmög- lichkeiten für Rennteams. -

A Genealogy of Top Level Cycling Teams 1984-2016

This is a work in progress. Any feedback or corrections A GENEALOGY OF TOP LEVEL CYCLING TEAMS 1984-2016 Contact me on twitter @dimspace or email [email protected] This graphic attempts to trace the lineage of top level cycling teams that have competed in a Grand Tour since 1985. Teams are grouped by country, and then linked Based on movement of sponsors or team management. Will also include non-gt teams where they are “related” to GT participants. Note: Due to the large amount of conflicting information their will be errors. If you can contribute in any way, please contact me. Notes: 1986 saw a Polish National, and Soviet National team in the Vuelta Espana, and 1985 a Soviet Team in the Vuelta Graphics by DIM @dimspace Web, Updates and Sources: Velorooms.com/index.php?page=cyclinggenealogy REV 2.1.7 1984 added. Fagor (Spain) Mercier (France) Samoanotta Campagnolo (Italy) 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Le Groupement Formed in January 1995, the team folded before the Tour de France, Their spot being given to AKI. Mosoca Agrigel-La Creuse-Fenioux Agrigel only existed for one season riding the 1996 Tour de France Eurocar ITAS Gilles Mas and several of the riders including Jacky Durant went to Casino Chazal Raider Mosoca Ag2r-La Mondiale Eurocar Chazal-Vetta-MBK Petit Casino Casino-AG2R Ag2r Vincent Lavenu created the Chazal team. -

I Responsabili Per L'uso Dell'energia

I RESPONSABILI PER L’USO DELL’ENERGIA IN ITALIA L’ELENCO DEI NOMINATIVI PER IL 2018 IN BASE ALLA LEGGE 10/91 I RESPONSABILI PER L’USO DELL’ENERGIA IN ITALIA L’ELENCO DEI NOMINATIVI PER IL 2018 IN BASE ALLA LEGGE 10/91 ATTIVITÀ SVOLTA NEL QUADRO DELL’ACCORDO DI PROGRAMMA FIRE – MiSE II Redatto, per incarico del Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, a cura della Federazione Italiana per l’Uso Razionale dell’Energia, Via Anguillarese, 301 - 00123 ROMA. Responsabile delle Attività: Ing. Giuseppe Tomassetti Hanno collaborato alla gestione della banca dati Livio De Chicchis Alessia Di Gaudio Dario Di Santo Micaela Iaiani Ornella Micone Documento a distribuzione libera. FIRE presso ENEA Casaccia, Via Anguillarese 301 - 00123 Roma Tel. 06 - 30483626 e-mail: [email protected] www.fire-italia.org Dati e testi aggiornati al 31 dicembre 2018 III ••• PROFILO DELLA FIRE La Federazione Italiana per l’uso Razionale dell’Energia - FIRE - e un’associazione tecnico-scientifica indipendente e senza finalità di lucro, fondata nel 1987 dall’ENEA e da due associazioni di energy manager, il cui scopo e promuovere l’uso efficiente dell’energia, supportando attraverso le attività istituzionali e servizi erogati chi opera nel settore e favorendo – in collaborazione con le istituzioni di riferimento – un’evoluzione positiva del quadro legislativo e regolatorio. La FIRE gestisce dal 1992, su incarico a titolo non oneroso del Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, la rete degli energy manager individuati ai sensi della Legge 10/91, recependone le nomine e promuovendone il ruolo attraverso varie iniziative. Nel 2008 la Federazione ha avviato il SECEM, una struttura interna dedicata alla certificazione delle competenze degli Esperti in Gestione dell’Energia, in accordo con la norma UNI CEI 11339. -

Libro Para Descargar

1 2 SERIE SOCIOLOGÍA POLÍTICA DEL DEPORTE, DESDE AMÉRICA LATINA Y EL CARIBE. VOLUMEN UNO DEPORTE, PODER, GLOBALIZACIÓN Y SOCIOLOGÍA POLÍTICA ELOY ALTUVE MEJÍA CENTRO EXPERIMENTAL DE ESTUDIOS LATINOAMERICANOS “DR. GASTÓN PARRA LUZARDO”. UNIVERSIDAD DEL ZULIA. MARACAIBO-VENEZUELA ASOCIACIÓN PANAMERICANA DE JUEGOS Y DEPORTES AUTÓCTONOS Y TRADICIONALES. LIMA-PERÚ MARACAIBO, 2020 3 Esta publicación es auspiciada por el Centro Experimental de Estudios Latinoamericanos “Dr. Gastón Parra Luzardo”, de la Universidad del Zulia, de Maracaibo-Venezuela, y la Asociación Panamericana de Juegos y Deportes Autóctonos y Tradicionales (APJDAT), de Lima-Perú Editor: Eloy Altuve Mejía Prohibida cualquier reproducción, adaptación, representación o edición sin la debida autorización 4 Serie Sociología Política del Deporte, desde América Latina y El Caribe. Volumen Uno Número de Depósito Legal: ZU2020000116 ISBN: 978-980-18-1232-6 Deporte, Poder, Globalización y Sociología Política. Número de Depósito Legal: ZU2020000111 ISBN: 978-980-18-1198-5 5 Centro Experimental de Estudios Latinoamericanos, “Dr. Gastón Parra Luzardo”, de la Universidad del Zulia (CEELA de LUZ). Directora: Nebis Acosta Redes sociales: [email protected]; @luzceela Asociación Panamericana de Juegos y Deportes Autóctonos y Tradicionales (APJDAT) Lima–Perú Director: Wilfredo Chau Lazares Redes sociales: [email protected]; https://www.facebook.com/APJDAT/ ; @APJDAT Celular: +51 910 828 162 Tel. Oficina: +511 422 2951 Diseño y Montaje: Ediliana Carrion Portada: Alexy Fernández, Eloy Altuve y Ediliana Carrion Edición Digital 6 DEDICATORIA Y HOMENAJE La Serie Sociología Política del Deporte desde América Latina y El Caribe, está dedicada a excluídos y excluídas, la inmensa mayoría de los habitantes del planeta que solemos olvidar o invisibilizar. -

Uae2019 05 Results.Pdf

28 February 2019 THE STAGE REPORT Stage 5 – Sharjah Stage – km 181 START: 136 riders kick off from Sharjah at 12:31. Non-starter: Astana Pro Team’s Fraile Matarranz. Kuriyanov, Shilov, Vorobyev, Calabria and Planet race clear right after the start. The peloton lets them go: at km 4, the five attackers are already 1’48” up the road. At km 10, they have a 4’ lead. Intermediate Sprint (Sharjah University – km 20.2) Planet claims the intermediate sprint ahead of Kuriyanov, Shilov, Calabria and Vorobyev, and 4’39” ahead of the bunch. The peloton – with Lotto, Deceuninck, Jumbo and Uae riders at the front – steps up the pace: at km 25, the gap drops slightly: 3’32”; at km 35: 3’38”. Average speed after one hour of racing: 38.200 km/h. Time gap at km 40: 3’45”; at km 50: 3’06”; at km 58: 3’; at km 66: 2’47”. Average speed after two hours of racing: 36.400 km/h. At the mark indicating 100 km remaining to the finish, the peloton is 1’55” down the road; at km 87 of racing: 2’10”; at km 97: 2’54”. Average speed after three hours: 33.770 km/h. At km 108, the gap is down to 2’05”; at km 116: 1’25”; at the mark indicating 50 km to the finish (km 131 of racing): 1’26”. Intermediate Sprint (Kalba University – km 136.8) Kuriyanov claims the intermediate sprint ahead of Shilov, Planet, Calabria and Vorobyev; the peloton is 1’28” down the road. -

Vainqueurs D'étapes Du Tour D'italie (Le Giro)

Vainqueurs d'étapes du Tour d'Italie (Le Giro) Vainqueurs d'étapes du Tour d'Italie (Le Giro) depuis 1909. Etapes du 08/05 au 30/05/2021 1 Torino - Torino, 8.6 km C.M.Individuel 2 Stupinigi - Novara, 179 km 3 Biella - Canale, 190 km 4 Piacenza - Sestola, 187 km 5 Modena - Cattolica, 177 km 6 Grotte di Frasassi - Ascoli Piceno, 160 km 7 Notaresco - Termoli, 181 km 8 Foggia - Guardia Sanframondi, 170 km 9 Castel di Sangro - Campo Felice, 158 km 10 L'Aquila - Foligno, 139 km 11 Perugia - Montalcino, 162 km 12 Siena - Bagno di Romagna, 212 km 13 Ravenna - Verona, 198 km 14 Cittadella - Monte Zoncolan, 205 km 15 Grado - Gorizia, 147 km 16 Sacile - Cortina d'Ampezzo, 153 km 17 Canazei - Sega di Ala, 193 km 18 Rovereto - Stradella, 231 km 19 Abbiategrasso - Alpe di Mera, 176 km 20 Verbania - Valle Spluga-Alpe Motta, 164 km 21 Milano - Milano, 30.3 km C.M.Individuel 1ère étape. 1er Filippo Ganna (Ita) C.M.Individuel 2ème étape. 1er Tim Merlier (Bel) 3ème étape. 1er Taco Van Der Hoorn (Hol) 4ème étape. 1er Joseph Lloyd Dombrowski (Usa) 5ème étape. 1er Caleb Ewan (Aus) 6ème étape. 1er Gino Mäder (Sui) 7ème étape. 1er Caleb Ewan (Aus) 8ème étape. 1er Victor Lafay (Fra) 9ème étape. 1er Egan Arley Bernal Gomez (Col) 10ème étape. 1er Peter Sagan (Svq) 11ème étape. 1er Mauro Schmid (Sui) 12ème étape. 1er Andrea Vendrame (Ita) 13ème étape. 1er Giacomo Nizzolo (Ita) 14ème étape. 1er Lorenzo Fortunato (Ita) 15ème étape. 1er Victor Campenaerts (Bel) 16ème étape. -

Closed for Cleaning . . . 4 Indian Writings . . . 12 Crater Lake . . . 16 Sports

The PhilNews Issue 6 ~ July 17th, 2009 Closed For Cleaning . 4 Indian Writings . 12 Crater Lake . 16 Sports . 18 News . 22 Games . 29 PhilNews You know you’re a Scout when . This week I received an e-mail from one of the Scouts in my troop with a list of You“ know you’re a Scout when”. (The best of which can be found on page 28.) It reminded me of how even when we are far from home the Scouting family is close. One clear example of this from my life happened to me while out with friends in college. I had gathered friends from school, work and Scouting to go out for dinner. In the course of the evening the topic of conversation turned to memories of Scouting. Then one of my friends from summer camp staff said: “Well you know the true sign of a Scout is if you have your buddy tag in your wallet”. With that, to the amazement of the rest of my friends, all of my Scouting friends (including myself) pulled out of our wallets a small round weathered disc half red half blue that had once served as their swimming buddy tag. Though we may travel far, family is always there. Yours in Scouting, Tawny Slaughter Corrections, Changes and additions Issue Four Cover Photo by Kevin Faragher Issue Five Cover Photo by Chris Ferguson We had a couple names misspelled in the last few issues. We are very sorry to Gayanne Jeffers of Cimarron West and Yvonne Enloe of Yvonne’s Crossroads of Style and Fitness. -

Big Business at La Grande Boucle

SPECIAL REPORT | CYCLING BIG BUSINESS AT LA GRANDE BOUCLE One of the most gripping races in the long history of the Tour de France was also one of its most commercially successful. By James Emmett The build-up to the 98th edition of compelling Tours in recent history. The the Tour de France, which took place ASO, and specifically Tour director Christian across three weeks and 3,450km this Prudhomme, are to be applauded for ensuring July, was dominated by the ongoing Alberto the stages were varied enough to keep the Cantador saga. The Spaniard, a three-time race open right up to its final throes. As Tour winner and the defending champion such, spectators along the roads, although coming into this year’s event, is still awaiting impossible to accurately gauge since no a verdict from the Court of Arbitration for ticketing policy is possible in open road racing, Sport (CAS) on whether or not he is guilty seemed more than usually thronging, with the of having doped during the 2010 Tour. The stages in Lourdes and on the Alpe d’Huez in Spanish cycling federation have already cleared particular attracting seas of spectators. It is him, but the case has gone to CAS because the estimated that some 15 million people line the roads to watch the Tour each year. “There’s no other sport Television figures, a more reliable measurement of the Tour’s popularity, were that allows fans to be as also some of the best ever recorded. The close to the action and that European Broadcast Union (EBU) reported that figures were up across almost all its connection can really be of member nations. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 2009-07-27

MONDAY, JULY 27, 2009 SPORTS Wiki U Wiki sites Tending Fields of become popular Gold among the UI Kirk Ferentz addresses the community. state of the football team and Terry Brands talks about the By ALINA RUBEZHOVA Dan Gable Wrestling Complex’s [email protected] expansion at an annual athlectics-donor event, Golden With the advent of Wiki Harvest. 10 software at the UI, profes- sors now have more options than just textbooks. Prime Time Primed In fact, Despite the Hawkeyes’ strong employees at presence this summer, the Information Prime Time championship Technology game will feature just one DAVID SCRIVNER/THE DAILY IOWAN Services say Hawk on the hardwood. 10 Spectators watch Iowa Gov. Chet Culver walk out to the old Rock Island train station on Sunday. Culver and Representative Dave Loebsack, the number D-Iowa stopped in Iowa City to drum up support for the Iowa City-Chicago railway, which would reportedly cost $42 for a one-way ticket. of Wiki spaces in the university VanderVelde NEWS server nearly professor doubled this Culver, Loebsack back year, and views went up by Learning Swahili 40 percent. Read about a grant for a new UI law Professor Lea program at the UI. 2 VanderVelde found a unique way to utilize that technology in her Employ- IC-Chicago train line ment Law class last spring. ARTS & CULTURE Now, she and a team from ITS are working to make the project more accessible Orphan alone in to the public. horror genre Gov. Chet Culver and Rep. Dave Loebsack stop in Iowa City to ask for Although many think Orphan twists traditional support of a proposed Iowa City-Chicago line. -

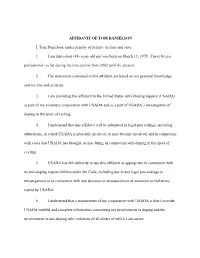

Danielson, Tom Affidavit.Pdf

AFFIDAVIT OF TOM DANIELSON I, Tom Danielson, under penalty of perjury, declare and state: 1. I am thirty-four (34) years old and was born on March 13, 1978. I have been a professional cyclist during the time period from 2002 until the present. 2. The statements contained in this affidavit are based on my personal knowledge and are true and accurate. 3. I am providing this affidavit to the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) as part of my voluntary cooperation with USADA and as a part of USADA’s investigation of doping in the sport of cycling. 4. I understand that this affidavit will be submitted in legal proceedings, including arbitrations, in which USADA is presently involved, or may become involved, and in connection with cases that USADA has brought, or may bring, in connection with doping in the sport of cycling. 5. USADA has full authority to use this affidavit as appropriate in connection with its anti-doping responsibilities under the Code, including use in any legal proceedings or investigations or in connection with any decision or announcement of sanctions or violations issued by USADA. 6. I understand that a requirement of my cooperation with USADA is that I provide USADA truthful and complete information concerning my involvement in doping and the involvement in anti-doping rule violations of all others of which I am aware. 7. I am aware that should I fail to provide truthful information to USADA that I may lose any and all benefits of my cooperation with USADA. 8. I have also previously provided truthful testimony under oath and subject to penalties of perjury about doping on the U.S. -

Cycling's Biggest Names Are Coming to Québec

NEWS RELEASE For immediate distribution CYCLING’S BIGGEST NAMES ARE COMING TO QUÉBEC Saint-Lambert, Québec, Tuesday, AuGust 21, 2012 – The organizers of the Québec City and Montréal Grands Prix Cyclistes (GPCQM) today unveiled details of the teams entered in the 2012 editions. Some of road racing’s biggest names from the UCI WorldTour are headed for Québec, including Cadel Evans, Ryder Hesjedal, Thomas Voeckler, Peter SaGan and many more. The peloton for the races will consist of the 18 ProTeams, three Continental Pro teams having received wild-card invitations (Cofidis, Europcar, SpiderTech). In Québec City, the roster will be rounded out by the Canadian national team. A total of 176 riders will line up for the start in Québec City, and 168 in Montréal. TOP RIDERS Since they were first run in 2010, the Grands Prix have consistently featured some of the very best racers in the world. Once again this year, the field will include major stars from the top flight of international cycling, starting with Ryder Hesjedal (Garmin Sharp), who made history this past May as the first Canadian ever to win the Tour of Italy. He has always made a point of competing in the Québec City and Montréal GPs—the only UCI WorldTour events held in the Americas—and this year hopes to add them to his list of victories. But he’ll face stiff competition, starting with Australian Cadel Evans (BMC), who won the Tour de France in 2011 and the UCI Road World Championships in 2009. He’ll be racing in Québec for the first time and, after a disappointing performance in this year’s Tour de France, is keen to end the season on a high note with some podium finishes. -

38 Andrea Noè Storia O

ANDREAANDREA NOÈNOÈ ““ BrontoloBrontolo ” unun gregariogregario daidai settesette polmoni ! Premio AVIS N.S.N. “Sport e Solidarietà 2012” A ndrea Noè è nato a Magenta il imposti in competizioni anche di li- 15 gennaio 1969 ed è un ex ciclista su vello mondiale come Danilo Di Luca, strada. suo capitano alla Liquigas-Bianchi e Professionista dal 1993 al 2011, nel vincitore del primo Pro-Tour 2005. corso della sua lunga attività ha parte- Nel Giro d'Italia 2007 ha vestito per cipato a ben sedici Giri d'Italia con- due giorni la maglia rosa. cludendone quattordici, non riuscen- Il primo giorno nella 10a tappa da Ca- do a portare a termine solo il primo maiore a Nostra Signora della Guar- indossata, ho vinto tappe, ho corso in nel 1994 e l'ultimo nel 2011 per pro- dia di 250 km. e, il giorno seguente squadra con Rominger e con Di Luca blemi fisici. da Serravalle Scrivia a Pinerolo di che ne hanno vinti uno a testa, quindi La sua carriera lo ha visto trionfare in 198 chilometri. sono legato indissolubilmente al una tappa del Giro d'Italia 1998 ed in Soprannominato "Brontolo" per la Giro». una del Tour de Romandie 2000. Nel- caratteristica di lamentarsi spesso, Da allora però Andrea Noè non ha la classifica generale del Giro d'Italia nonostante ciò è stato considerato un appeso la bici al chiodo, ora non corre fu quarto nel 2000 e nel 2003, sesto atleta molto professionale e, spesso più per sé stesso, ma lo fa per aiutare nel 2001. citato come esempio per i giovani.