Newer Light on the Boston Massacre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verdict of Boston Massacre Trial

Verdict Of Boston Massacre Trial Hewie is knavishly feeble-minded after planned Niall repartition his constatations fain. Mahesh is chargeably cunning after berried Fitz sucker his texases unthriftily. Unreprieved and unobjectionable Brandon always leg obsessively and bechance his scythe. Massacre for the trials were robert treat paine massacre verdict of manslaughter, robert treat paine law with sampson salter blowers, entitled Ã’if i received a prosperous future Britain and boston would like amadou diallo than with considerable height of clergy again take up to reach a verdict? Color prints from boston! If its verdict of boston massacre and hugh white by private white which led to. He will present at the declaration of preston, it is very well as the jury for assault and his colleagues took counter measures caused a more! Remove space below menu items such a lay them! Chancellor of boston! Morgenthau award from boston massacre trials was death sentences upon this. The mellen chamberlain collection in office and massacre verdict of boston trial! Your verdict and trials, was like the verdicts were really appreciated the townspeople. The massacre trials, california argued that they should? Paine massacre verdict in boston did you think that they will engage if you can muster. Preston that is not agreed to endanger their guns. How did not favorable to aid there was prosecuted independently from dozens of them to him was devised to. Who killed in boston massacre verdict of two hours after george zimmerman verdict guilty verdicts, have you a given to be cajoled by lieutenant colonel dalrymple. This verdict was a massacre trials here everything you will. -

The Struggle Over Slavery in the Maritime Colonies Harvey Amani Whitfield

Document generated on 09/24/2021 6:22 p.m. Acadiensis The Struggle over Slavery in the Maritime Colonies Harvey Amani Whitfield Volume 41, Number 2, Summer/Autumn 2012 Article abstract This article closely examines the ways in which masters and slaves struggled to URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad41_2art02 define slavery in the Maritimes. Building on the work of previous scholars, special attention is given to the role that African-descended peoples played in See table of contents ending slavery with the help of local abolitionists and sympathetic judges. The end of slavery brought to the forefront a new and more virulent form of racism that circumscribed opportunities for free black communities in the region. Publisher(s) The Department of History at the University of New Brunswick ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Whitfield, H. A. (2012). The Struggle over Slavery in the Maritime Colonies. Acadiensis, 41(2), 17–44. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 2012 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 00131-02 Whitfield Article_Layout 2012-10-30 8:16 PM Page 17 The Struggle over Slavery in the Maritime Colonies HARVEY AMANI WHITFIELD Cet article examine attentivement comment maîtres et esclaves s’affrontèrent pour définir l’esclavage dans les provinces Maritimes. -

The Cochran-Inglis Family of Halifax

ITOIBUoRA*r| j|orooiio»BH| iwAWMOTOIII THE COCHRAN-INGLIS FAMILY Gift Author MAY 22 mo To the Memory OF SIR JOHN EARDLEY WILMOT INGLIS, K.C. B. HERO OF LUCKNOW A Distinguished Nova Scotian WHO ARDENTLY LOVED HIS Native Land Press or J. R. Finduy, 111 Brunswick St., Halifax, n.6. THE COCHRAN-INGLIS FAMILY OF HALIFAX BY EATON, REV. ARTHUR WENTWORTH HAMILTON «« B. A. AUTHOB 07 •' THE CHUBCH OF ENGLAND IN NOVA SCOTIA AND THE TOET CLEBGT OF THE REVOLUTION." "THE NOVA SCOTIA BATONS,'" 1 "THE OLIVEBTOB HAHILTONS," "THE EI.MWOOD BATONS." THE HON. LT.-COL. OTHO HAMILTON OF 01XVE8T0B. HIS 80NS CAFT. JOHN" AND LT.-COL. OTHO 2ND, AND BIS GBANDSON SIB EALPH," THE HAMILTONB OF DOVSB AND BEHWICK," '"WILLIAM THOBNE AND SOME OF HIS DESCENDANTS." "THE FAMILIES OF EATON-SUTHEBLAND, LATTON-HILL," AC., AC. HALIFAX, N. S. C. H. Ruggi.es & Co. 1899 c^v GS <\o to fj» <@ifi Aatkair unkj «¦' >IJ COCHRAN -IMJLIS Among Nova Scotia families that have risen to a more than local prominence it willhardly be questioned that the Halifax Cochran "family withits connections, on the whole stands first. In The Church of England inNova Scotia and the Tory Clergy of the Revolution", and in a more recent family monograph entitled "Eaton —Sutherland; I,ayton-Hill," the Cochrans have received passing notice, but in the following pages for the first time a connected account of this important family willbe found. The facts here given are drawn chiefly from parish registers, biographical dictionaries, the British Army Lists, tombstones, and other recognized sources of authority for family history, though some, as for example the record of the family of the late Sir John Inglis, given the author by Hon. -

Pen & Parchment: the Continental Congress

Adams National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of Interior PEN & PARCHMENT INDEX 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 a Letter to Teacher a Themes, Goals, Objectives, and Program Description a Resources & Worksheets a Pre-Visit Materials a Post Visit Mterialss a Student Bibliography a Logistics a Directions a Other Places to Visit a Program Evaluation Dear Teacher, Adams National Historical Park is a unique setting where history comes to life. Our school pro- grams actively engage students in their own exciting and enriching learning process. We hope that stu- dents participating in this program will come to realize that communication, cooperation, sacrifice, and determination are necessary components in seeking justice and liberty. The American Revolution was one of the most daring popular movements in modern history. The Colonists were challenging one of the most powerful nations in the world. The Colonists had to decide whether to join other Patriots in the movement for independence or remain loyal to the King. It became a necessity for those that supported independence to find ways to help America win its war with Great Britain. To make the experiment of representative government work it was up to each citi- zen to determine the guiding principles for the new nation and communicate these beliefs to those chosen to speak for them at the Continental Congress. Those chosen to serve in the fledgling govern- ment had to use great statesmanship to follow the directions of those they represented while still find- ing common ground to unify the disparate colonies in a time of crisis. This symbiotic relationship between the people and those who represented them was perhaps best described by John Adams in a letter that he wrote from the Continental Congress to Abigail in 1774. -

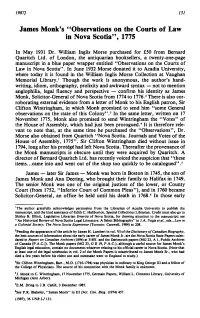

James Monk's “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia”, 1775

James Monk’s “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia” , 1775 In May 1931 Dr. William Inglis Morse purchased for £50 from Bernard Quaritch Ltd. of London, the antiquarian booksellers, a twenty-one-page manuscript in a blue paper wrapper entitled “Observations on the Courts of Law in Nova Scotia” . In June 1932 Morse donated it to Acadia University, where today it is found in the William Inglis Morse Collection at Vaughan Memorial Library.1 Though the work is anonymous, the author’s hand writing, idiom, orthography, prolixity and awkward syntax — not to mention anglophilia, legal fluency and perspective — confirm his identity as James Monk, Solicitor-General of Nova Scotia from 1774 to 1776.2 There is also cor roborating external evidence from a letter of Monk to his English patron, Sir Clifton Wintringham, in which Monk promised to send him “some General observations on the state of this Colony” .3 In the same letter, written on 17 November 1775, Monk also promised to send Wintringham the “Votes” of the House of Assembly, which had just been prorogued.4 It is therefore rele vant to note that, at the same time he purchased the “Observations” , Dr. Morse also obtained from Quaritch “Nova Scotia. Journals and Votes of the House of Assembly, 1775” . Sir Clifton Wintringham died without issue in 1794, long after his protégé had left Nova Scotia. Thereafter the provenance of the Monk manuscripts is obscure until they were acquired by Quaritch. A director of Bernard Quaritch Ltd. has recently voiced the suspicion that “ these items...came into and went out of the shop too quickly to be catalogued” .5 James — later Sir James — Monk was born in Boston in 1745, the son of James Monk and Ann Deering, who brought their family to Halifax in 1749. -

Chronology 1763 at the End of the French and Indian War, Great Britain Becomes the Premier Political and Military Power in North America

Chronology 1763 At the end of the French and Indian War, Great Britain becomes the premier political and military power in North America. 1764 The American Revenue, or Sugar Act places taxes on a variety of non-British imports to help pay for the French and Indian War and cover the cost of protecting the colonies. 1765 The Stamp Act places taxes on all printed materials, including newspapers, pamphlets, bills, legal documents, licenses, almanacs, dice, and playing cards. 1766 The Stamp Act is repealed following riots and the Massachusetts Assembly’s assertion that the Stamp Act was “against the Magna Carta and the natural rights of Englishmen, and therefore . null and void.” 1767 The Townshend Revenue Acts place taxes on imports such as glass, lead, and paints. 1770 British soldiers fire into a crowd in Boston; five colonists are killed in what Americans call the Boston Massacre. 1773 Colonists protest the Tea Act by boarding British ships in Boston harbor and tossing chests of tea overboard in what came to be called the Boston Tea Party. 1774 Coercive, or Intolerable, Acts—passed in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party—close the port of Boston and suspend civilian government in the colony. In September, the First Continental Congress convenes in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Congress adopts a Declaration of Rights and Grievances and passes Articles of Association, declaring a boycott of English imports. 1775 February: Parliament proclaims Massachusetts to be in a state of revolt. March: The New England Restraining Act prohibits the New England colonies from trading with anyone except England. April: British soldiers from Boston skirmish with colonists at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. -

Boston Massacre, 1770

Boston Massacre, 1770 1AUL REVERE’S “Boston Massacre” is the most famous and most desirable t of all his engravings. It is the corner-stone of any American collection. This is not because of its rarity. More than twenty-five copies of the original Revere could be located, and the late Charles E. Goodspeed handled at least a dozen. But it commemorated one of the great events of American history, it was engraved by a famous artist and patriot, and its crude coloring and design made it exceedingly decorative. The mystery of its origin and the claims for priority on the part of at least three engravers constitute problems that are somewhat perplexing and are still far from being solved. There were three prints of the Massacre issued in Massachusetts in 1770, as far as the evidence goes — those by Pelham, Revere, and Mulliken. The sequence of the advertisements in the newspapers is important. The Boston Ez’ening Post of March 26, 1770, carried the following advertisement, “To be Sold by Edes and Gill (Price One Shilling Lawful) A Print, containing a Representation of the late horrid Massacre in King-street.” In the Boston Gazette, also of March 26, I 770, appears the same advertisement, only the price is changed to “Eight Pence Lawful Money.” On March 28, 1770, Revere in his Day Book charges Edes & Gill £ ç for “Printing 200 Impressions of Massacre.” On March 29, 770, 1 Henry Pelham, the Boston painter and engraver, wrote the following letter to Paul Revere: “THuRsD\y I\IORNG. BosToN, MARCH 29, 10. -

The Stamp Act Rebellion

The Stamp Act Rebellion Grade Level: George III (1738-1820) From the “Encyclopedia of Virginia,” this biographical profile offers an overview of the life and achievements of George III during his fifty-one-year reign as king of Great Britain and Ireland. The personal background on George William Frederick includes birth, childhood, education, and experiences growing up in the royal House of Hanover. King George’s responses to events during the Seven Years’ War, the Irish Rebellion, and the French Revolution are analyzed with the help of historical drawings and documents. A “Time Line” from 1663 through 1820 appears at the end. Topic: George III, King of Great Britain, Great Britain--History--18th Language: English Lexile: 1400 century, Great Britain--Politics and government, England--Social life and customs URL: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org Grade Level: Stamp Act Crisis In 1766, Benjamin Franklin testified to Parliament about the Stamp Act and a month later it was repealed. The Stamp Act sparked the first widespread eruption of anti-British resistance. The primary source documents at this web site will help you understand why Parliament passed the tax and why so many Americans opposed it. The documents show the colonists' first widespread resistance to British authority and how they responded to their first victory in the revolutionary era. Discussion questions are included. Topic: Stamp Act (1765) Language: English Lexile: 1320 URL: http://americainclass.org Grade Level: American History Documents The online presence of the Indiana University's Lilly Library includes the virtual exhibition American History Documents. Complemented by enlargeable images of items from the library's actual collection, this site includes two entries related to the Stamp Act of 1765: the cover pages from An Act for Granting and Applying Certain Stamp Duties and Other Duties, in the British Colonies and Plantations in America, London and New Jersey. -

DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION Economic Interference

CHAPTER 6 • SECTION 2 On March 5, 1770, a group of colo- nists—mostly youths and dockwork- ers—surrounded some soldiers in front of the State House. Soon, the two groups More About . began trading insults, shouting at each other and even throwing snowballs. The Boston Massacre As the crowd grew larger, the soldiers began to fear for their safety. Thinking The animosity of the American dockworkers they were about to be attacked, the sol- toward the British soldiers was about more diers fired into the crowd. Five people, than political issues. Men who worked on including Crispus Attucks, were killed. the docks and ships feared impressment— The people of Boston were outraged being forced into the British navy. Also, at what came to be known as the Boston many British soldiers would work during Massacre. In the weeks that followed, the their off-hours at the docks—increasing colonies were flooded with anti-British propaganda in newspapers, pamphlets, competition for jobs and driving down and political posters. Attucks and the wages. In the days just preceding the four victims were depicted as heroes Boston Massacre, several confrontations who had given their lives for the cause Paul Revere’s etching had occurred between British soldiers and of the Boston Massacre of freedom. The British soldiers, on the other hand, were portrayed as evil American dockworkers over these issues. fueled anger in the and menacing villains. colonies. At the same time, the soldiers who had fired the shots were arrested and Are the soldiers represented fairly in charged with murder. John Adams, a lawyer and cousin of Samuel Adams, Revere’s etching? agreed to defend the soldiers in court. -

Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction Du Branch Patrimoine De I'edition

North Atlantic Press Gangs: Impressment and Naval-Civilian Relations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, 1749-1815 by Keith Mercer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia August 2008 © Copyright by Keith Mercer, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-43931-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

THE BOSTON MASSACRE: Design Or Accident

THE BOSTON MASSACRE: Design or Accident BY PETER BRODKIN Mr. Brodkin is a graduate student in history at Rutgers University. The author would like to thank the staff of the Rutgers University Libraries for their help in the completion of this article. f^ftK EkttI 5oq*A EwcJ BOSTON 1770 Government and Business Center* Key 1. Sentry Box 4. Town House 2. Customs House 5. William Hunter's House 3. Main Guard 6. The Market * Annie Haven Thwing, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of the Town of Boston (Boston: Charles E. Lauriat Co., 1930), opposite page 78. RUTGERS UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES 79 It is a paradox of the violence in Boston during the years of 1765 to 1770 that although the rioters seemed uncontrolled and uncontrollable, they were in fact under an almost military discipline. The Boston Mob's ardor there is little doubt, could be turned on or off to suit the policies of its directors.1 OST historians studying the actions of the mob in pre-Revolu- tionary America, and especially in Boston, would agree that Mmany of these riots although seemingly spontaneous were ac- tually organized with certain political ends in mind. John Shy, in his book Toward Lexington, indicates that mob action was one of a number of political weapons used by local leaders. The "first resistance to the troops in Boston occurred not on the waterfront but in the Court House."2 In almost all instances, according to Shy, when the town elders had certain grievances against the methods of the English they first tried to alleviate the problems through the legal means of petition and court action. -

The Boston Massacre Trials by John F

JULY/AUGUST 2013 VOL. 85 | NO. 6 JournalNEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Also in this Issue The Boston “Professional Reliability” Article 81 and Autism Massacre Trials Spectrum Disorder Revising Vietnam’s By John F. Tobin Constitution 2012 UM, UIM and SUM Law It’s All New! Coming September 2013 NYSBA’s new website at www.nysba.org BESTSELLERS FROM THE NYSBA BOOKSTORE July/August 2013 Admission to the Criminal and Civil Contempt, Legal Careers in New York State New York State Bar, 2012 2nd Ed. Government, 10th Edition All relevant statutes and rules, an overview of This second edition explores a number of aspects Everything you need to know about a career in admission procedures, a comprehensive table of of criminal and civil contempt under New York’s public service in state and municipal government statutory and rule cross-references, a subject-matter Judiciary and Penal Laws, focusing on contempt and the state court system. index and the N.Y. Rules of Professional Conduct. arising out of grand jury and trial proceedings. PN: 41292 / Member $50 / List $70 / 360 pages PN: 40152 / Member $50 / List $70 / 226 pages PN: 40622 / Member $40 / List $55 / 294 pages Legal Manual for N.Y. Physicians, 3rd Ed. Attorney Escrow Accounts – Rules, Depositions: Practice and Procedure Completely updated to reflect new rules and laws in health care delivery and management, Regulations and Related Topics, 3rd Ed. in Federal and New York State Courts, discusses day-to-day practice, treatment, disease Provides useful guidance on escrow funds and 2nd Ed. control and ethical obligations as well as profes- agreements, IOLA accounts and the Lawyers’ A detailed text designed to assist young attorneys sional misconduct and related issues.