A Call to Liberty: Rhetoric and Reality in the American Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All Hands Are Enjoined to Spin : Textile Production in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts." (1996)

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1996 All hands are enjoined to spin : textile production in seventeenth- century Massachusetts. Susan M. Ouellette University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Ouellette, Susan M., "All hands are enjoined to spin : textile production in seventeenth-century Massachusetts." (1996). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1224. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1224 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST c c: 315DLDb0133T[] i !3 ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by SUSAN M. OUELLETTE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 1996 History ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS A Dissertation Presented by SUSAN M. OUELLETTE Approved as to style and content by: So Barry/ J . Levy^/ Chair c konJL WI_ Xa LaaAj Gerald McFarland, Member Neal Salisbury, Member Patricia Warner, Member Bruce Laurie, Department Head History (^Copyright by Susan Poland Ouellette 1996 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ALL HANDS ARE ENJOINED TO SPIN: TEXTILE PRODUCTION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MASSACHUSETTS FEBRUARY 1996 SUSAN M. OUELLETTE, B.A., STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PLATTSBURGH M.A., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Ph.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Directed by: Professor Barry J. -

Pen & Parchment: the Continental Congress

Adams National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of Interior PEN & PARCHMENT INDEX 555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555555 a Letter to Teacher a Themes, Goals, Objectives, and Program Description a Resources & Worksheets a Pre-Visit Materials a Post Visit Mterialss a Student Bibliography a Logistics a Directions a Other Places to Visit a Program Evaluation Dear Teacher, Adams National Historical Park is a unique setting where history comes to life. Our school pro- grams actively engage students in their own exciting and enriching learning process. We hope that stu- dents participating in this program will come to realize that communication, cooperation, sacrifice, and determination are necessary components in seeking justice and liberty. The American Revolution was one of the most daring popular movements in modern history. The Colonists were challenging one of the most powerful nations in the world. The Colonists had to decide whether to join other Patriots in the movement for independence or remain loyal to the King. It became a necessity for those that supported independence to find ways to help America win its war with Great Britain. To make the experiment of representative government work it was up to each citi- zen to determine the guiding principles for the new nation and communicate these beliefs to those chosen to speak for them at the Continental Congress. Those chosen to serve in the fledgling govern- ment had to use great statesmanship to follow the directions of those they represented while still find- ing common ground to unify the disparate colonies in a time of crisis. This symbiotic relationship between the people and those who represented them was perhaps best described by John Adams in a letter that he wrote from the Continental Congress to Abigail in 1774. -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

Loyalist Literary Activity in the Maritimes

GWENDOLYN DA VIES Consolation To Distress: Loyalist Literary Activity in the Maritimes THE LOYALIST MIGRATION INTO THE Maritime provinces has often been examined for its social, economic, and political impact, but it is also to the Loyalists that literary historians must turn in any discussion of creative activity in the area during the early years of its cultural development. Among the approximately 30,000 refugees settling in the region were a number of the most active literary figures of the Revolutionary war period, including such well- respected Tory satirists as Jonathan Odell, Jacob Bailey, and Joseph Stansbury, and a number of lesser-known occasional writers like Mather By les, Jr., Roger Viets, Joshua Wingate Weeks, and Deborah How Cottnam. Bringing with them a sophistication of literary experience and a taste for lyric and satiric writing hitherto unknown in the region, these authors were part of a wider Loyalist cultural phenomenon that saw the founding of a literary periodical, the establishment of schools and classical colleges, the endorsement of theatrical performances, the development of newspapers and printing shops, the organiza tion of agricultural and reading societies, and the writing of polite literature as part of the fabric of conventional society. Looking to their old life as a measure of their new, Loyalist exiles in the Maritimes did much to develop the expectations, structures, and standards of taste necessary for the growth of a literary environment. Although economics, geography, politics, and personal differences militated against their founding a literary movement between 1776 and 1814 or leaving behind an identifiable literary tradition, the Loyalists did illustrate the imaginative and cultural possibilities awaiting a later, more securely-established generation of writers. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

Chronology 1763 at the End of the French and Indian War, Great Britain Becomes the Premier Political and Military Power in North America

Chronology 1763 At the end of the French and Indian War, Great Britain becomes the premier political and military power in North America. 1764 The American Revenue, or Sugar Act places taxes on a variety of non-British imports to help pay for the French and Indian War and cover the cost of protecting the colonies. 1765 The Stamp Act places taxes on all printed materials, including newspapers, pamphlets, bills, legal documents, licenses, almanacs, dice, and playing cards. 1766 The Stamp Act is repealed following riots and the Massachusetts Assembly’s assertion that the Stamp Act was “against the Magna Carta and the natural rights of Englishmen, and therefore . null and void.” 1767 The Townshend Revenue Acts place taxes on imports such as glass, lead, and paints. 1770 British soldiers fire into a crowd in Boston; five colonists are killed in what Americans call the Boston Massacre. 1773 Colonists protest the Tea Act by boarding British ships in Boston harbor and tossing chests of tea overboard in what came to be called the Boston Tea Party. 1774 Coercive, or Intolerable, Acts—passed in retaliation for the Boston Tea Party—close the port of Boston and suspend civilian government in the colony. In September, the First Continental Congress convenes in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Congress adopts a Declaration of Rights and Grievances and passes Articles of Association, declaring a boycott of English imports. 1775 February: Parliament proclaims Massachusetts to be in a state of revolt. March: The New England Restraining Act prohibits the New England colonies from trading with anyone except England. April: British soldiers from Boston skirmish with colonists at the Battles of Lexington and Concord. -

Boston Massacre, 1770

Boston Massacre, 1770 1AUL REVERE’S “Boston Massacre” is the most famous and most desirable t of all his engravings. It is the corner-stone of any American collection. This is not because of its rarity. More than twenty-five copies of the original Revere could be located, and the late Charles E. Goodspeed handled at least a dozen. But it commemorated one of the great events of American history, it was engraved by a famous artist and patriot, and its crude coloring and design made it exceedingly decorative. The mystery of its origin and the claims for priority on the part of at least three engravers constitute problems that are somewhat perplexing and are still far from being solved. There were three prints of the Massacre issued in Massachusetts in 1770, as far as the evidence goes — those by Pelham, Revere, and Mulliken. The sequence of the advertisements in the newspapers is important. The Boston Ez’ening Post of March 26, 1770, carried the following advertisement, “To be Sold by Edes and Gill (Price One Shilling Lawful) A Print, containing a Representation of the late horrid Massacre in King-street.” In the Boston Gazette, also of March 26, I 770, appears the same advertisement, only the price is changed to “Eight Pence Lawful Money.” On March 28, 1770, Revere in his Day Book charges Edes & Gill £ ç for “Printing 200 Impressions of Massacre.” On March 29, 770, 1 Henry Pelham, the Boston painter and engraver, wrote the following letter to Paul Revere: “THuRsD\y I\IORNG. BosToN, MARCH 29, 10. -

The Stamp Act Rebellion

The Stamp Act Rebellion Grade Level: George III (1738-1820) From the “Encyclopedia of Virginia,” this biographical profile offers an overview of the life and achievements of George III during his fifty-one-year reign as king of Great Britain and Ireland. The personal background on George William Frederick includes birth, childhood, education, and experiences growing up in the royal House of Hanover. King George’s responses to events during the Seven Years’ War, the Irish Rebellion, and the French Revolution are analyzed with the help of historical drawings and documents. A “Time Line” from 1663 through 1820 appears at the end. Topic: George III, King of Great Britain, Great Britain--History--18th Language: English Lexile: 1400 century, Great Britain--Politics and government, England--Social life and customs URL: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org Grade Level: Stamp Act Crisis In 1766, Benjamin Franklin testified to Parliament about the Stamp Act and a month later it was repealed. The Stamp Act sparked the first widespread eruption of anti-British resistance. The primary source documents at this web site will help you understand why Parliament passed the tax and why so many Americans opposed it. The documents show the colonists' first widespread resistance to British authority and how they responded to their first victory in the revolutionary era. Discussion questions are included. Topic: Stamp Act (1765) Language: English Lexile: 1320 URL: http://americainclass.org Grade Level: American History Documents The online presence of the Indiana University's Lilly Library includes the virtual exhibition American History Documents. Complemented by enlargeable images of items from the library's actual collection, this site includes two entries related to the Stamp Act of 1765: the cover pages from An Act for Granting and Applying Certain Stamp Duties and Other Duties, in the British Colonies and Plantations in America, London and New Jersey. -

Otis Speech on Writs of Assistance

Copyright OUP 2013 AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM VOLUME I: STRUCTURES OF GOVERNMENT Howard Gillman • Mark A. Graber • Keith E. Whittington Supplementary Material Chapter 2: The Colonial Era – Judicial Power and Constitutional Authority James Otis, Part of Speech before the Superior Court of Massachusetts on the Writs of Assistance (1761)1 3 In 1761, the Superior Court of Massachusetts heard arguments on whether it should issue writs of assistance to colonial custom officials who were attempting to enforce British trade laws against local1 merchants smuggling goods. The writs would provide legal authority for officials to conduct forcible searches, on their own initiative, of private property throughout the Boston area. Before the court, James Otis raised what quickly became famous objections to the legality and constitutionality of the writs. 0 The argument of Otis particularly stood out for its assertion that an act authorizing writs of general assistance would be unconstitutional and therefore void. In support of this assertion, Otis 2cited Dr. Bonham’s Case (8 Co. 107a [1610]), in which the great English jurist Sir Edward Coke asserted that “in many cases, the common law will control acts of parliament, and sometimes adjudge them utterly void: for when an act of parliament is against common right and reason, or repugnant, or impossible to be performed, the common law will control it, and adjudge such act to be void.” The argument was subsequently important forP helping to lay the basis for the development of American judicial review after the Revolution. The Superior Court did not rule immediately, but instead sought further information from England as to whether such writs were still in use there. -

DIFFERENTIATING INSTRUCTION Economic Interference

CHAPTER 6 • SECTION 2 On March 5, 1770, a group of colo- nists—mostly youths and dockwork- ers—surrounded some soldiers in front of the State House. Soon, the two groups More About . began trading insults, shouting at each other and even throwing snowballs. The Boston Massacre As the crowd grew larger, the soldiers began to fear for their safety. Thinking The animosity of the American dockworkers they were about to be attacked, the sol- toward the British soldiers was about more diers fired into the crowd. Five people, than political issues. Men who worked on including Crispus Attucks, were killed. the docks and ships feared impressment— The people of Boston were outraged being forced into the British navy. Also, at what came to be known as the Boston many British soldiers would work during Massacre. In the weeks that followed, the their off-hours at the docks—increasing colonies were flooded with anti-British propaganda in newspapers, pamphlets, competition for jobs and driving down and political posters. Attucks and the wages. In the days just preceding the four victims were depicted as heroes Boston Massacre, several confrontations who had given their lives for the cause Paul Revere’s etching had occurred between British soldiers and of the Boston Massacre of freedom. The British soldiers, on the other hand, were portrayed as evil American dockworkers over these issues. fueled anger in the and menacing villains. colonies. At the same time, the soldiers who had fired the shots were arrested and Are the soldiers represented fairly in charged with murder. John Adams, a lawyer and cousin of Samuel Adams, Revere’s etching? agreed to defend the soldiers in court. -

The American Experiment

The American2 Experiment Assignment government, where majority desires have an even greater impact on the government. This lesson is based on information in the following Although these ideas are associated with the devel- text selections and video. Carefully read and review opment of the U.S. Constitution, they have their roots all of the materials before taking the practice test. in the preceding colonial and revolutionary experi- The key terms, focus points, and practice test are in- ences in America. The colonists’ English heritage had tended to help ensure mastery of the essential politi- stressed the ideas of both limited government and cal issues surrounding the background and creation self-government. To a large extent, the American rev- of the U.S. Constitution. olutionaries were seeking to retain what they had tra- ditionally understood to be their rights as Text: Chapter 2, “Constitutional Democracy: Pro- Englishmen. Controversy between the American col- moting Liberty and Self-Government,” pp. onists and the English developed in the aftermath of 37–48 the French and Indian War, when the British govern- ment sought to impose several new taxes in order to Declaration of Independence, Appendix A raise revenue. The British first enacted the Stamp Act, then the Townshend Act, and then a tax on tea. Video: “The American Experiment” Because they had no representatives in the English Parliament, the colonists were convinced that these taxes violated the principle of “no taxation without Overview representation,” a right recognized by Englishmen. The colonists met together to articulate their griev- Events like the Watergate break-in during the Nixon ances against the British crown at the First Continen- Administration demonstrate that Americans still tal Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. -

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

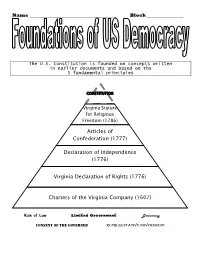

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3.