NATIONAL LIFE STORIES CITY LIVES Martin Gordon Interviewed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

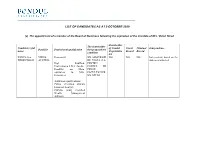

OGM 2. List of Candidates As at 9 October 2020

___________________________________________________________________________________________________ LIST OF CANDIDATES AS AT 9 OCTOBER 2020 (a) The appointment of a member of the Board of Nominees following the expiration of the mandate of Mrs. Vivian Nicoli Shareholder The shareholder Candidate’s full of Fondul Fiscal Criminal Independence Domicile Professional qualification that proposed the name Proprietatea Record Record candidate SA ILINCA von VIENA, Economist NN ASIGURARI NO NO NO Independent, based on the DERENTHALL AUSTRIA DE VIATA S.A. statement attached Dipl. Kauffrau, PENTRU Universitatea J.W.v. Goethe, FONDUL DE Frankfurt am Main, PENSII equivalent to MSc. FACULTATIVE Economics NN OPTIM Additional qualifications: CEFA (Certified EFFAS Financial Analyst), CWMA (SAQ Certified Wealth Management Advisor) ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ (b) The appointment of a member of the Board of Nominees following the expiration of the mandate of Mr. Steven van Groningen Shareholder Independence The shareholder Candidate’s full of Fondul Fiscal Criminal Professional qualification that proposed the name Domicile Proprietatea Record Record candidate SA OVIDIU FER BUCHAREST, Economist J&T Banka NO NO NO The Sole Director does ROMANIA believe Mr. Ovidiu Fer Academy of Economic may not meet the Studies – Romania, Major independence conditions in Finance, Insurance, because of the partnership Banking and Stock with a former Exchange representative of Fondul Proprietatea SA and INSEAD, -

Journal Association of Jewish Refugees

VOLUME 7 NO.4 APRIL 2007 journal Association of Jewish Refugees Prisoners remembered, prisoners forgotten Researching my article on Herbert Sulzbach captives persisted down the decades. for our February issue, I was amazed at the This fascination does not extend to extent to which the history of German British PoWs in the First World War, about prisoners-of-war in Britain has fallen into whom very little is knovro. At most, a few oblivion. Today, nobody seems to know that people will have heard of the camp at there were some 400,000 German PoWs in Ruhleben, near Berlin, where British Britain in 1946, dispersed all over the civilians were interned. The presence of country in some 1,500 camp units. I even numerous British and French PoWs in discovered a mini-camp in Brondesbury Germany during the First World War also Park, London NW6, about two miles from vanished rapidly from German public where I live, where prisoners from Wilton consciousness, unlike that of Russian PoWs, Park in Buckinghamshire, selected to whose suffering is vividly depicted in such broadcast on the BBC, were lodged in bestsellers as Amold Zweig's Der Streit um London. Yet the record of the British in re den Sergeanten Grischa and E. M. educating the PoWs in their charge was Remarque's Im Westen nichts Neues. The thoroughly creditable. The official German fate of the Russian PoWs came to symbolise history of German PoWs in the Second the senseless suffering of the ordinary World War explicitly acknowledges that soldier in a hopeless war, which was the Britain surpassed all other custodian powers main lesson of the First World War for in teaching PoWs to respect democratic liberal intellectuals in post-1918 Germany. -

Paul M. Warburg: Founder of the United States Federal Reserve Richard A

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU History Faculty Publications History Department 5-13-2013 Paul M. Warburg: Founder of the United States Federal Reserve Richard A. Naclerio Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/his_fac Part of the Economic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Naclerio, Richard A., "Paul M. Warburg: Founder of the United States Federal Reserve" (2013). History Faculty Publications. Paper 99. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/his_fac/99 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paul M. Warburg: Founder of the United States Federal Reserve Prof. Richard A. Naclerio May 13, 2013 Paul Moritz Warburg The name Paul Moritz Warburg is synonymous with the founding of the Federal Reserve System. Warburg’s impact on American banking is a parallel to his family’s impact on European banking. The epic story of the Warburg family of European bankers can be traced back to the early 1500s when Simon von Cassel settled in the German Westphalia town of Warburg (originally founded by Charlemagne in 778 and was then known as Warburgum) and began the family’s quest for money and financial power. Although the Warburgs excelled in many other occupations throughout Europe, it was this lineage that produced some of the most successful bankers in the world. Blessed with sharp minds and good business sense, the generations of the Warburg clan gained seemingly boundless money and power. -

21St Annual St. Louis Jewish Film Festival 21St Annual St

“A Reel World Tour” (Clayton Rd and Lindbergh) (Clayton Rd 21st Annual St.Festival Jewish Film Louis 2016 June 5-9, Cinema • Frontenac Plaza Landmark A Program of the Jewish Community Center 2 Millstone Campus Drive St. Louis, MO 63146 stljewishfilmfestival.org 314 442-3179 Advertising Supplement to the St. Louis Jewish Light Opening Day Double Feature Sunday, June 5 IN SEARCH OF ISRAELI CUISINE NORMAN LEAR: 4:00 PM JUST A DIFFERENT VERSION OF YOU 7:00 PM U.S.A. U.S.A. English/Hebrew with English Subtitles English Director: Roger Sherman Director: Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady Documentary: 97 Minutes Documentary: 90 minutes A mouth-watering treat…A portrait of the Israeli people told through Producer, writer, activist…Still working at 93, Norman Lear, the food, the film profiles chefs, home cooks, farmers, vintners, and cheese man behind such hugely influential shows as All in the Family, Sanford makers drawn from the more than 100 cultures of today’s Israel – and Son, The Jeffersons, Good Times, and Maude, also produced films Jewish, Arab, Muslim, Christian. Through interviews at farms, markets, including Stand By Me, The Princess Bride, and Fried Green Tomatoes. restaurants, kitchens, landscapes, and history—audiences will discover Featuring interviews with Lear and George Clooney, Bill Moyers, that this hot, multi-cultural cuisine has developed only in the last 30 John Amos, Amy Poehler, Jon Stewart, and others, the film focuses on years. Israel’s people and their food are secular, outward looking and points in Lear’s life that help to understand the man under the iconic hat. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Rckblicke, by Dr. Rer. Pol. Walter Grnfeld ** This Is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg Ebook, Deta

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rckblicke, by Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Copyright (C) 1998 by Frank Dekker This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Rckblicke Author: Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld Release Date: December, 2004 [EBook #7049C] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on February 28, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: German Character set encoding: Latin-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, RUECKBLICKE, BY GRUENFELD *** Copyright (C) 1998 by Frank Dekker Rckblicke Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld Inhaltsverzeichnis Kapitel 1 Frhes Panorama und Vorgeschichte Kapitel 2 Die Familie und Kattowitz Kapitel 3 Kindheit und frhe Jugend Kapitel 4 Kattowitz kommt zu Polen Kapitel 5 Als Student in der Weimarer Republik A) Berlin a) Leben und Studium b) ... und politische Bettigung B) Mnchen C) Zwischen Breslau und zu Hause Kapitel 6 Nach dem Ende von Weimar Kapitel 7 Emigration nach Hause, in Polen Kapitel 8 Der 2. -

Off the Tracks Volume 2

Works Cited Aanstoos, Christopher M., Ilene Serlin and Thomas Greening. (2000). History of Division 32 (Humanistic Psychology) of the American Psychological Association.In: Donald A. Dewsbury, ed. Unification through Division: Histories of the Divisions of the American Psychological Association, Vol. V. (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Abbott, Frank C. Report of the Committee on the Professions, Case #8128. (August 18, 1981). New York State Department of Education. Acocella, Joan. (1999). Creating Hysteria: Women and Multiple Personality Disorder. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Albarelli, H.P., Jr. (2009). A Terrible Mistake: The Murder of Frank Olson and the CIA’s Secret Cold War Experiments. New York: Trine Day. Alexander, Franz. (1960). Gregory Zilboorg. Bulletin of the American Psychoanalytic Association 16:380–381. ________. (December 16, 1941). Letter to Board of Directors, New York Psychoanalytic Society. A.A. Brill Library, New York Psychoanalytic Society & Institute. ________. (December 16, 1941). The Qualifications of a Psychoanalyst. A.A. Brill Library, New York Psychoanalytic Society & Institute. Alexander, Franz and Hugo Staub, tr. Gregory Zilboorg. (1931). The Criminal, the Judge, and the Public: A Psychological Analysis. New York: Macmillan. Alexander, Ilonka Venier. (2015). The Life and Times of Franz Alexander: From Budapest to California. London: History of Psychoanalysis Series, Karnac. Alexander, Jack. (December, 1941). “The Richest Boy in the World” Becomes Our No. 1 Angel. Saturday Evening Post. Alexander, Peter N., dir. (2001). The Profit. 1007 OFF THE TRACKS VOLUME 2 Alimurung, Gendy. (December 5, 2013). A Hypnotherapist Built a Career on Alien Abductions, and Her Experiences May Unnerve You. (Accessed February 8, 2016). LA Weekly. http://www.laweekly.com/news/a-hypnotherapist-built-a-career-on-alien- abductions-and-her-experiences-may-unnerve-you-4137401. -

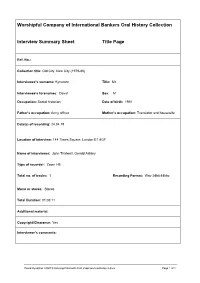

Transcript of Interview with David Kynaston (Historian)

Worshipful Company of International Bankers Oral History Collection Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref. No.: Collection title: Old City, New City (1979-86) Interviewee’s surname: Kynaston Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: David Sex: M Occupation: Social historian Date of birth: 1951 Father’s occupation: Army officer Mother’s occupation: Translator and housewife Date(s) of recording: 24.04.19 Location of interview: 144 Times Square, London E1 8GF Name of interviewer: John Thirlwell, Gerald Ashley Type of recorder: Zoom H5 Total no. of tracks: 1 Recording Format: Wav 24bit 48khz Mono or stereo: Stereo Total Duration: 01:03:11 Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Yes Interviewer’s comments: David Kynaston 240419 transcript final with front sheet and endnotes-3.docx Page 1 of 1 Introduction and biography #00:00:00# A club no more: changes from the pre-1980’s village; the #00:0##### aluminium war; Lord Cobbold #00:07:36# Factors of change and external pressures; effects of the abolition of Exchange Control; minimum commissions and single and dual capacity The Stock Exchange ownership question; opening ip to #00:12:17# foreign competition; silly prices paid for firms Cazenove & Co – John Kemp-Welch on partnership and #00:14:57# trust; US capital; Cazenove capital raising Motivations of Big Bang; Philips & Drew; John Craven and #00:18:22# ‘top dollar’ Lloyd’s of London #00:22:26# Bank of England; Margaret Thatcher’s view of the City and #00:25:07# vice versa and her relationship with the Governor, Lord Cobbold Robin Leigh-Pemberton -

The Federal Reserve Cartel: the Rothschild, Rockefeller and Morgan

DIFFERENTLIFE.NET NEWS TERMS OF SERVICE PRIVACY POLICY The Federal Reserve You Might Also Like Cartel: The You Might Also Like Rothschild, Rockefeller and Morgan Families ! October 27, 2019 " adpublisher # Social $ 0 You Might Also Like You Might Also Like Part One: The Banking Houses of Morgan and Rockefeller The Four Horsemen of Banking (Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup and Wells Fargo) own the Four Horsemen of Oil (Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch/Shell, BP and Chevron Texaco); in tandem with Deutsche Bank, BNP, Barclays and other European old money behemoths. But their monopoly over the global economy does not end at the edge of the oil patch. According to company 10K filings to the SEC, the Four Horsemen of Banking are among the top ten stock holders of virtually every Fortune 500 corporation.[1] So who then are the stockholders in these money center banks? This information is guarded much more closely. My queries to bank regulatory agencies regarding stock ownership in the top 25 US bank holding companies were given Freedom of Information Act status, before being denied on “national security” grounds. This is rather ironic, since many of the bank’s stockholders reside in Europe. One important repository for the wealth of the global oligarchy that owns these bank holding companies is US Trust Corporation – founded in 1853 and now owned by Bank of America. A recent US Trust Corporate Director and Honorary Trustee was Walter Rothschild. Other directors included Daniel Davison of JP Morgan Chase, Richard Tucker of Exxon Mobil, Daniel Roberts of Citigroup and Marshall Schwartz of Morgan Stanley. -

The Jewish Encyclopedia

T H E J E W I S H E N C Y C L O P E D I A A GU ID E TO ITS CO NTE N TS A N A ID TO ITS U S E O S E P H A C O BS J J , Rsvxs c EDITO R FU N K WAGNALLS CO M PAN Y N E W YO R K A N D LO N D ON 1906 PR E FACE IN the followin a es I g p g have endeavored , at the s Funk Wa nalls m an reque t of the g Co p y, to give such an account of the contents of THE J E WISH E N C CLO E DIA s as Y P , publi hed by them , will indicate the n u n at re of the work in co siderable detail , and at the same time facil itate the systematic use of it in any of i i ts very varied sections . For th s purpose it has been found necessary to divide the subj ect- matter of the E N CYCLO PE DIA in a somewhat different manner from that adopted for editorial purposes in the various departments . Several sections united under the con trol of one editor have been placed in more logical order in ff e a di er nt parts of the following ccount , while , on the other hand , sections which were divided among different editors have here been brought together under one head. In justice to my colleagues it is but fair to add that they are in no sense responsible for this - redistribution of the subject matter , or indeed for any of the views which either explicitly or by implication are expressed in the following pages on some of the disputed points affecting modern Jews and Judaism . -

1914 and 1939

APPENDIX PROFILES OF THE BRITISH MERCHANT BANKS OPERATING BETWEEN 1914 AND 1939 An attempt has been made to identify as many merchant banks as possible operating in the period from 1914 to 1939, and to provide a brief profle of the origins and main developments of each frm, includ- ing failures and amalgamations. While information has been gathered from a variety of sources, the Bankers’ Return to the Inland Revenue published in the London Gazette between 1914 and 1939 has been an excellent source. Some of these frms are well-known, whereas many have been long-forgotten. It has been important to this work that a comprehensive picture of the merchant banking sector in the period 1914–1939 has been obtained. Therefore, signifcant efforts have been made to recover as much information as possible about lost frms. This listing shows that the merchant banking sector was far from being a homogeneous group. While there were many frms that failed during this period, there were also a number of new entrants. The nature of mer- chant banking also evolved as stockbroking frms and issuing houses became known as merchant banks. The period from 1914 to the late 1930s was one of signifcant change for the sector. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 361 under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 B. O’Sullivan, From Crisis to Crisis, Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96698-4 362 Firm Profle T. H. Allan & Co. 1874 to 1932 A 17 Gracechurch St., East India Agent. -

Terrorism Illuminati

t er r o r ism AN D T H E Illu m in at i a t h r ee t h o u sa n d yea r h ist o r y by d av id Liv in g sto n e TERRORISM AND THE ILLUMINATI TERRORISM AND THE ILLUMINATI A Three Thousand Year HISTORy DAVID LIVINGSTONE BOOKSURGE LLC TERRORISM AND THE ILLUMINATI A Three Thousand Year History All Rights Reserved © 2007 by David Livingstone No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. BookSurge LLC For information address: BookSurge LLC An Amazon.com company 7290 B Investment Drive Charleston, SC 29418 www.booksurge.com ISBN: 1-4196-6125-6 Printed in the United States of America And among mankind there is he whose talk “ about the life of this world will impress you, and he calls “ on God as a witness to what is in his heart. Yet, he is the most stringent of opponents. The Holy Koran, chapter 2: 204 If the American people knew what we have done, “ “ they would string us up from the lamp posts. George H.W. Bush Table of Contents Introduction: The Clash of Civilizations 1 Chapter 1: The Lost Tribes The Luciferian Bloodline 7 The Fallen Angels 8 The Medes 11 The Scythians 13 Chapter 2: The Kabbalah Zionism 15 The Chaldean Magi 16 Ancient Greece 17 Plato 19 Alexander 22 Chapter 3: Mithraism Cappadocia 25 The Mithraic Bloodline 28 The Jewish Revolt 32 The Mysteries of Mithras 33 Chapter 4: Gnosticism Herod the Great 37 Paul the Gnostic -

Authorized Catalogs - United States

Authorized Catalogs - United States Miché-Whiting, Danielle Emma "C" Vic Music @Canvas Music +2DB 1 Of 4 Prod. 10 Free Trees Music 10 Free Trees Music (Admin. by Word Music Group, 1000 lbs of People Publishing 1000 Pushups, LLC Inc obo WB Music Corp) 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers SESAC Designee 10000 MINUTES 1012 Rosedale Music 10KF Publishing 11! Music 12 Gate Recordings LLC 121 Music 121 Music 12Stone Worship 1600 Publishing 17th Avenue Music 19 Entertainment 19 Tunes 1978 Music 1978 Music 1DA Music 2 Acre Lot 2 Dada Music 2 Hour Songs 2 Letit Music 2 Right Feet 2035 Music 21 Cent Hymns 21 DAYS 21 Songs 216 Music 220 Digital Music 2218 Music 24 Fret 243 Music 247 Worship Music 24DLB Publishing 27:4 Worship Publishing 288 Music 29:11 Church Productions 29:Eleven Music 2GZ Publishing 2Klean Music 2nd Law Music 2nd Law Music 2PM Music 2Surrender 2Surrender 2Ten 3 Leaves 3 Little Bugs 360 Music Works 365 Worship Resources 3JCord Music 3RD WAVE MUSIC 4 Heartstrings Music 40 Psalms Music 442 Music 4468 Productions 45 Degrees Music 4552 Entertainment Street 48 Flex 4th Son Music 4th teepee on the right music 5 Acre Publishing 50 Miles 50 States Music 586Beats 59 Cadillac Music 603 Publishing 66 Ford Songs 68 Guns 68 Guns 6th Generation Music 716 Music Publishing 7189 Music Publishing 7Core Publishing 7FT Songs 814 Stops Today 814 Stops Today 814 Today Publishing 815 Stops Today 816 Stops Today 817 Stops Today 818 Stops Today 819 Stops Today 833 Songs 84Media 88 Key Flow Music 9t One Songs A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd A Beautiful Liturgy Music A Few Good Tunes A J Not Y Publishing A Little Good News Music A Little More Good News Music A Mighty Poythress A New Song For A New Day Music A New Test Catalog A Pirates Life For Me Music A Popular Muse A Sofa And A Chair Music A Thousand Hills Music, LLC A&A Production Studios A.