Transcript of Interview with David Kynaston (Historian)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

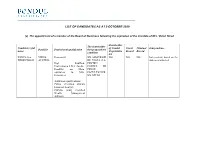

OGM 2. List of Candidates As at 9 October 2020

___________________________________________________________________________________________________ LIST OF CANDIDATES AS AT 9 OCTOBER 2020 (a) The appointment of a member of the Board of Nominees following the expiration of the mandate of Mrs. Vivian Nicoli Shareholder The shareholder Candidate’s full of Fondul Fiscal Criminal Independence Domicile Professional qualification that proposed the name Proprietatea Record Record candidate SA ILINCA von VIENA, Economist NN ASIGURARI NO NO NO Independent, based on the DERENTHALL AUSTRIA DE VIATA S.A. statement attached Dipl. Kauffrau, PENTRU Universitatea J.W.v. Goethe, FONDUL DE Frankfurt am Main, PENSII equivalent to MSc. FACULTATIVE Economics NN OPTIM Additional qualifications: CEFA (Certified EFFAS Financial Analyst), CWMA (SAQ Certified Wealth Management Advisor) ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ (b) The appointment of a member of the Board of Nominees following the expiration of the mandate of Mr. Steven van Groningen Shareholder Independence The shareholder Candidate’s full of Fondul Fiscal Criminal Professional qualification that proposed the name Domicile Proprietatea Record Record candidate SA OVIDIU FER BUCHAREST, Economist J&T Banka NO NO NO The Sole Director does ROMANIA believe Mr. Ovidiu Fer Academy of Economic may not meet the Studies – Romania, Major independence conditions in Finance, Insurance, because of the partnership Banking and Stock with a former Exchange representative of Fondul Proprietatea SA and INSEAD, -

Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990

From ‘as British as Finchley’ to ‘no selfish strategic interest’: Thatcher, Northern Ireland and Anglo-Irish Relations, 1979-1990 Fiona Diane McKelvey, BA (Hons), MRes Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Ulster University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words excluding the title page, contents, acknowledgements, summary or abstract, abbreviations, footnotes, diagrams, maps, illustrations, tables, appendices, and references or bibliography Contents Acknowledgements i Abstract ii Abbreviations iii List of Tables v Introduction An Unrequited Love Affair? Unionism and Conservatism, 1885-1979 1 Research Questions, Contribution to Knowledge, Research Methods, Methodology and Structure of Thesis 1 Playing the Orange Card: Westminster and the Home Rule Crises, 1885-1921 10 The Realm of ‘old unhappy far-off things and battles long ago’: Ulster Unionists at Westminster after 1921 18 ‘For God's sake bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country’: 1950-1974 22 Thatcher on the Road to Number Ten, 1975-1979 26 Conclusion 28 Chapter 1 Jack Lynch, Charles J. Haughey and Margaret Thatcher, 1979-1981 31 'Rise and Follow Charlie': Haughey's Journey from the Backbenches to the Taoiseach's Office 34 The Atkins Talks 40 Haughey’s Search for the ‘glittering prize’ 45 The Haughey-Thatcher Meetings 49 Conclusion 65 Chapter 2 Crisis in Ireland: The Hunger Strikes, 1980-1981 -

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES CITY LIVES Martin Gordon Interviewed

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES CITY LIVES Martin Gordon Interviewed by Louise Brodie C409/134 This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk. © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators Martin Gordon C409/134/F5288-A/Part 1 F5288 Side A [This is the 8th of August 1996. Louise Brodie talking to Martin Gordon.] Could you tell me where and when you were born please? I was born on the 19th of July 1938, the year of the Tiger. I was born in Kensington, in St. Mary Abbot's Terrace. My father was an economist. And, my father had been born in Italy at the beginning of the century; my mother had been born in China in 1913, where her father had been practising as a doctor in Manchuria. Therefore I came from a very international background, albeit my family was a Scottish-English family and I was born in London, but I always had a very strong international inclination from my parents and from other members of my family around the world. -

Journal Association of Jewish Refugees

VOLUME 7 NO.4 APRIL 2007 journal Association of Jewish Refugees Prisoners remembered, prisoners forgotten Researching my article on Herbert Sulzbach captives persisted down the decades. for our February issue, I was amazed at the This fascination does not extend to extent to which the history of German British PoWs in the First World War, about prisoners-of-war in Britain has fallen into whom very little is knovro. At most, a few oblivion. Today, nobody seems to know that people will have heard of the camp at there were some 400,000 German PoWs in Ruhleben, near Berlin, where British Britain in 1946, dispersed all over the civilians were interned. The presence of country in some 1,500 camp units. I even numerous British and French PoWs in discovered a mini-camp in Brondesbury Germany during the First World War also Park, London NW6, about two miles from vanished rapidly from German public where I live, where prisoners from Wilton consciousness, unlike that of Russian PoWs, Park in Buckinghamshire, selected to whose suffering is vividly depicted in such broadcast on the BBC, were lodged in bestsellers as Amold Zweig's Der Streit um London. Yet the record of the British in re den Sergeanten Grischa and E. M. educating the PoWs in their charge was Remarque's Im Westen nichts Neues. The thoroughly creditable. The official German fate of the Russian PoWs came to symbolise history of German PoWs in the Second the senseless suffering of the ordinary World War explicitly acknowledges that soldier in a hopeless war, which was the Britain surpassed all other custodian powers main lesson of the First World War for in teaching PoWs to respect democratic liberal intellectuals in post-1918 Germany. -

Plutocracy: the Marketising of ‘Equality’ Within Neoliberalism

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Littler, J. (2013). Meritocracy as plutocracy: the marketising of ‘equality’ within neoliberalism. New Formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 80-81, pp. 52-72. doi: 10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/4167/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MERITOCRACY AS PLUTOCRACY: THE MARKETISING OF ‘EQUALITY’ UNDER NEOLIBERALISM Jo Littler Abstract Meritocracy, in contemporary parlance, refers to the idea that whatever our social position at birth, society ought to facilitate the means for ‘talent’ to ‘rise to the top’. This article argues that the ideology of ‘meritocracy’ has become a key means through which plutocracy is endorsed by stealth within contemporary neoliberal culture. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Rckblicke, by Dr. Rer. Pol. Walter Grnfeld ** This Is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg Ebook, Deta

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rckblicke, by Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Copyright (C) 1998 by Frank Dekker This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Rckblicke Author: Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld Release Date: December, 2004 [EBook #7049C] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on February 28, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: German Character set encoding: Latin-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, RUECKBLICKE, BY GRUENFELD *** Copyright (C) 1998 by Frank Dekker Rckblicke Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld Inhaltsverzeichnis Kapitel 1 Frhes Panorama und Vorgeschichte Kapitel 2 Die Familie und Kattowitz Kapitel 3 Kindheit und frhe Jugend Kapitel 4 Kattowitz kommt zu Polen Kapitel 5 Als Student in der Weimarer Republik A) Berlin a) Leben und Studium b) ... und politische Bettigung B) Mnchen C) Zwischen Breslau und zu Hause Kapitel 6 Nach dem Ende von Weimar Kapitel 7 Emigration nach Hause, in Polen Kapitel 8 Der 2. -

The Da Vinci Delusion Unions—Their Great Failure What's Wrong With

middle class and broke: new polls issue 208 | july 2013 www.prospect-magazine.co.uk july 2013 | £4.50 Britain’s folly in Syria britain’s folly in syria Plus The Da Vinci delusion CliVe James Unions—their great failure DaViD gooDharT What’s wrong with France? ChrisTine oCkrenT We’re all machiavelli now JonaThan poWell poet of postwar Britain JonaThan Coe True cost of eU exit: richard lambert In 1912 Malcolm Campbell christened his car “Blue Bird” and a legend was born. More than 100 years later this iconic marque continues to challenge for world speed records using futuristic electric vehicles. Christopher Ward is proud to be the Official Timing Partner for Bluebird and, to celebrate our partnership we have released this exceptional timepiece in a limited edition of 1,912 pieces. 174_ChristopherWard_Prospect.indd 1 10/06/2013 08:16 174_ChristopherWard_Prospect.indd 2 10/06/2013 08:16 We explore further. Aberdeen Investment Trusts ISA and Share Plan At Aberdeen, we believe there’s no substitute for getting to know your investments face-to-face. That’s why we make it our goal to visit companies – wherever they are – before we ever invest in their shares and again when we hold them. With 17 investment companies investing around the world – that’s an awfully big commitment. But it’s just one of the ways we aim to seek out the best investment opportunities on your behalf. Please remember, the value of shares and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may get back less than the amount invested. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997

Holders of Ministerial Office in the Conservative Governments 1979-1997 Parliamentary Information List Standard Note: SN/PC/04657 Last updated: 11 March 2008 Author: Department of Information Services All efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of this data. Nevertheless the complexity of Ministerial appointments, changes in the machinery of government and the very large number of Ministerial changes between 1979 and 1997 mean that there may be some omissions from this list. Where an individual was a Minister at the time of the May 1997 general election the end of his/her term of office has been given as 2 May. Finally, where possible the exact dates of service have been given although when this information was unavailable only the month is given. The Parliamentary Information List series covers various topics relating to Parliament; they include Bills, Committees, Constitution, Debates, Divisions, The House of Commons, Parliament and procedure. Also available: Research papers – impartial briefings on major bills and other topics of public and parliamentary concern, available as printed documents and on the Intranet and Internet. Standard notes – a selection of less formal briefings, often produced in response to frequently asked questions, are accessible via the Internet. Guides to Parliament – The House of Commons Information Office answers enquiries on the work, history and membership of the House of Commons. It also produces a range of publications about the House which are available for free in hard copy on request Education web site – a web site for children and schools with information and activities about Parliament. Any comments or corrections to the lists would be gratefully received and should be sent to: Parliamentary Information Lists Editor, Parliament & Constitution Centre, House of Commons, London SW1A OAA. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Tribune, December 3, 1943, in Paul Anderson ed. Orwell in Tribune (London: Politico’s, 2006), 57. 2. Margaret Tapster, WW2 People’s War, an online archive of wartime memories con- tributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/ 65/a5827665.shtml Accessed May 30, 2013. 3. Paul Addison, No Turning Back: The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); Peter Hennessy, Having It So Good: Britain in the Fifties (London: Allen Lane, 2006); David Kynaston Aus- terity Britain, 1945–51 (London, Berlin and New York: Bloomsbury, 2007); David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–1957 (London, Berlin, New York: Bloomsbury, 2009); Mark Donnelly, Sixties Britain: Culture, Society and Politics (Harlow: Pearson, 2005); Alwyn W. Turner, Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s (London: Aurum Press, 2008); Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber and Faber, 2009); Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979 (London: Allen Lane, 2012); Alwyn W. Turner, Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s (London: Aurum, 2010) and Andy McSmith, No Such Thing as Society: A History of Britain in the 1980s (London: Constable, 2011). 4. British and European resistance to American culture is expounded by Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London and New York: Routledge, 1979); Rob Kroes et al. Cultural Transmissions and Receptions: American Mass Culture in Europe (Amsterdam: VU University Press, 1993) and Rob Kroes, If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen the Mall: Europeans and American Mass Culture (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996). -

1914 and 1939

APPENDIX PROFILES OF THE BRITISH MERCHANT BANKS OPERATING BETWEEN 1914 AND 1939 An attempt has been made to identify as many merchant banks as possible operating in the period from 1914 to 1939, and to provide a brief profle of the origins and main developments of each frm, includ- ing failures and amalgamations. While information has been gathered from a variety of sources, the Bankers’ Return to the Inland Revenue published in the London Gazette between 1914 and 1939 has been an excellent source. Some of these frms are well-known, whereas many have been long-forgotten. It has been important to this work that a comprehensive picture of the merchant banking sector in the period 1914–1939 has been obtained. Therefore, signifcant efforts have been made to recover as much information as possible about lost frms. This listing shows that the merchant banking sector was far from being a homogeneous group. While there were many frms that failed during this period, there were also a number of new entrants. The nature of mer- chant banking also evolved as stockbroking frms and issuing houses became known as merchant banks. The period from 1914 to the late 1930s was one of signifcant change for the sector. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 361 under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 B. O’Sullivan, From Crisis to Crisis, Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96698-4 362 Firm Profle T. H. Allan & Co. 1874 to 1932 A 17 Gracechurch St., East India Agent. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit ..................................................................................................................................................