Arxiv:2003.03982V3 [Astro-Ph.HE] 7 May 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathématiques Et Espace

Atelier disciplinaire AD 5 Mathématiques et Espace Anne-Cécile DHERS, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Peggy THILLET, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Yann BARSAMIAN, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Olivier BONNETON, Sciences - U (mathématiques) Cahier d'activités Activité 1 : L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL Activité 2 : DENOMBREMENT D'ETOILES DANS LE CIEL ET L'UNIVERS Activité 3 : D'HIPPARCOS A BENFORD Activité 4 : OBSERVATION STATISTIQUE DES CRATERES LUNAIRES Activité 5 : DIAMETRE DES CRATERES D'IMPACT Activité 6 : LOI DE TITIUS-BODE Activité 7 : MODELISER UNE CONSTELLATION EN 3D Crédits photo : NASA / CNES L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL (3 ème / 2 nde ) __________________________________________________ OBJECTIF : Détermination de la ligne d'horizon à une altitude donnée. COMPETENCES : ● Utilisation du théorème de Pythagore ● Utilisation de Google Earth pour évaluer des distances à vol d'oiseau ● Recherche personnelle de données REALISATION : Il s'agit ici de mettre en application le théorème de Pythagore mais avec une vision terrestre dans un premier temps suite à un questionnement de l'élève puis dans un second temps de réutiliser la même démarche dans le cadre spatial de la visibilité d'un satellite. Fiche élève ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Victor Hugo a écrit dans Les Châtiments : "Les horizons aux horizons succèdent […] : on avance toujours, on n’arrive jamais ". Face à la mer, vous voyez l'horizon à perte de vue. Mais "est-ce loin, l'horizon ?". D'après toi, jusqu'à quelle distance peux-tu voir si le temps est clair ? Réponse 1 : " Sans instrument, je peux voir jusqu'à .................. km " Réponse 2 : " Avec une paire de jumelles, je peux voir jusqu'à ............... km " 2. Nous allons maintenant calculer à l'aide du théorème de Pythagore la ligne d'horizon pour une hauteur H donnée. -

Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Second Edition

RASC Observing Committee Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Second Edition Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Welcome to the Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Program. This program is designed to provide the observer with a well-rounded introduction to the night sky visible from North America. Using this observing program is an excellent way to gain knowledge and experience in astronomy. Experienced observers find that a planned observing session results in a more satisfying and interesting experience. This program will help introduce you to amateur astronomy and prepare you for other more challenging certificate programs such as the Messier and Finest NGC. The program covers the full range of astronomical objects. Here is a summary: Observing Objective Requirement Available Constellations and Bright Stars 12 24 The Moon 16 32 Solar System 5 10 Deep Sky Objects 12 24 Double Stars 10 20 Total 55 110 In each category a choice of objects is provided so that you can begin the certificate at any time of the year. In order to receive your certificate you need to observe a total of 55 of the 110 objects available. Here is a summary of some of the abbreviations used in this program Instrument V – Visual (unaided eye) B – Binocular T – Telescope V/B - Visual/Binocular B/T - Binocular/Telescope Season Season when the object can be best seen in the evening sky between dusk. and midnight. Objects may also be seen in other seasons. Description Brief description of the target object, its common name and other details. Cons Constellation where object can be found (if applicable) BOG Ref Refers to corresponding references in the RASC’s The Beginner’s Observing Guide highlighting this object. -

The Heavens in August a Study of Short Period Variables

100 SCIENTIFIC,AMERlCAN July 31, 1915 The Heavens in August A Study of Short Period Variables By Prof. Henry Norris Russell, Ph.D. HE warm clear nights of summer offer the amateur which is marked on our map, .and the second lies about and but 18 minutes of arc apart, while Neptune is only T the best chance for star-gazing in all the year, and, two fifths of the way from this to () Ophiuchi (also a degree away on the other side. This simultaneous fortunately, he has one of the finest portions of the shown on the map) and is the only bright star near conjunction of three planets is rather remarkable, but, heavens at his command in the splendid region of the this line. The character of the variation is in both as they rise less than an hour earlier than the Sun, Milky Way, which stretches from Cassiopeia and cases very similar to that of the stars previously de Neptune will be utterly invisible, though the other two Cygnus through Aquila to Sagittarius and Scorpio, and scribed. w Sagittarii varies from magnitude 4.3 to 5.1 planets may easily be seen with a telescope (provided forms a vast circle right across the summit of the vault in a period of 7.595 days, the ris� in brightness taking with suitable finding circles ) even in broad daylight, of heaven. about half as long as the fall, and the maximum being and in the same low-power field. The veriest novice can learn in an hour to identify a little more than twice the minimum light. -

LIST of PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Aryabhatta Research Institute of Observational Sciences ARIES (An Autonomous Scientific Research Institute of Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India) Manora Peak, Naini Tal - 263 129, India (1955−2020) ABBREVIATIONS AA: Astronomy and Astrophysics AASS: Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series ACTA: Acta Astronomica AJ: Astronomical Journal ANG: Annals de Geophysique Ap. J.: Astrophysical Journal ASP: Astronomical Society of Pacific ASR: Advances in Space Research ASS: Astrophysics and Space Science AE: Atmospheric Environment ASL: Atmospheric Science Letters BA: Baltic Astronomy BAC: Bulletin Astronomical Institute of Czechoslovakia BASI: Bulletin of the Astronomical Society of India BIVS: Bulletin of the Indian Vacuum Society BNIS: Bulletin of National Institute of Sciences CJAA: Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics CS: Current Science EPS: Earth Planets Space GRL : Geophysical Research Letters IAU: International Astronomical Union IBVS: Information Bulletin on Variable Stars IJHS: Indian Journal of History of Science IJPAP: Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics IJRSP: Indian Journal of Radio and Space Physics INSA: Indian National Science Academy JAA: Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy JAMC: Journal of Applied Meterology and Climatology JATP: Journal of Atmospheric and Terrestrial Physics JBAA: Journal of British Astronomical Association JCAP: Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics JESS : Jr. of Earth System Science JGR : Journal of Geophysical Research JIGR: Journal of Indian -

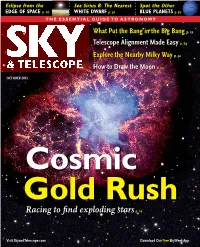

Sky & Telescope

Eclipse from the See Sirius B: The Nearest Spot the Other EDGE OF SPACE p. 66 WHITE DWARF p. 30 BLUE PLANETS p. 50 THE ESSENTIAL GUIDE TO ASTRONOMY What Put the Bang in the Big Bang p. 22 Telescope Alignment Made Easy p. 64 Explore the Nearby Milky Way p. 32 How to Draw the Moon p. 54 OCTOBER 2013 Cosmic Gold Rush Racing to fi nd exploding stars p. 16 Visit SkyandTelescope.com Download Our Free SkyWeek App FC Oct2013_J.indd 1 8/2/13 2:47 PM “I can’t say when I’ve ever enjoyed owning anything more than my Tele Vue products.” — R.C, TX Tele Vue-76 Why Are Tele Vue Products So Good? Because We Aim to Please! For over 30-years we’ve created eyepieces and telescopes focusing on a singular target; deliver a cus- tomer experience “...even better than you imagined.” Eyepieces with wider, sharper fields of view so you see more at any power, Rich-field refractors with APO performance so you can enjoy Andromeda as well as Jupiter in all their splendor. Tele Vue products complement each other to pro- vide an observing experience as exquisite in performance as it is enjoyable and effortless. And how do we score with our valued customers? Judging by superlatives like: “in- credible, truly amazing, awesome, fantastic, beautiful, work of art, exceeded expectations by a mile, best quality available, WOW, outstanding, uncom- NP101 f/5.4 APO refractor promised, perfect, gorgeous” etc., BULLSEYE! See these superlatives in with 110° Ethos-SX eye- piece shown on their original warranty card context at TeleVue.com/comments. -

134, December 2007

British Astronomical Association VARIABLE STAR SECTION CIRCULAR No 134, December 2007 Contents AB Andromedae Primary Minima ......................................... inside front cover From the Director ............................................................................................. 1 Recurrent Objects Programme and Long Term Polar Programme News............4 Eclipsing Binary News ..................................................................................... 5 Chart News ...................................................................................................... 7 CE Lyncis ......................................................................................................... 9 New Chart for CE and SV Lyncis ........................................................ 10 SV Lyncis Light Curves 1971-2007 ............................................................... 11 An Introduction to Measuring Variable Stars using a CCD Camera..............13 Cataclysmic Variables-Some Recent Experiences ........................................... 16 The UK Virtual Observatory ......................................................................... 18 A New Infrared Variable in Scutum ................................................................ 22 The Life and Times of Charles Frederick Butterworth, FRAS........................24 A Hard Day’s Night: Day-to-Day Photometry of Vega and Beta Lyrae.........28 Delta Cephei, 2007 ......................................................................................... 33 -

David Levy's Guide to the Night Sky Da

Cambridge University Press 0521797535 - David Levy’s Guide to the Night Sky David H. Levy Index More information INDEX AAVSO, 200–201, 331, 332 binoculars, 57–59 absolute magnitudes, 36 Bobrovnikoff method, estimating comet Adams, John Couch, 156 brightness, 178 aetheria darkening, 138 Bode, Johann, 163 Alcock, George, 44, 185 Bode’s Law, 163–165 Algol, 325 Brahe, Tycho, 81 aligning, 67 Brasch, Klaus, 126 Alpha Capricornids, 47 Brashear, John, 60 altazimuth, 62, 65 bright nebulae, 232–233 altitude, 67 Brooks, William, 182 Amalthea, 111 Burnham, Sherbourne Wesley, 193 amateur astronomy, introduced, xvii, xviii Andromedids, 48, 49, 68 Callisto, 111, 119, 121 Antoniadi, Eugenios, 112 Carrington, Christopher, 103 aphelic oppositions, 134 Cassini spacecraft, 130 aphelion, 134 Cassini, Giovanni, 81, 124 apochromat, 60 Cassini’s Division, 124, 125 apparent magnitude, 36 CCD technology, 275–280 apparitions, of comets, 134, 135 CCDs, for astrometry, 283 Arago, Francois, 156 Celestial Police, 163–164 Ariel, 159 celestial equator, 8 ashen light, Venus, 152 Central Bureau for Astronomical Association of Lunar and Planetary Telegrams,120, 121, 186–187, 280 Observers, 331, 332 Challis, James, 156 Asteroids, 163–172 Chapman, Clark, 170 naming of, 165–166 Chaucer, Geoffrey, 318 Astronomical League, 333 chromosphere, 293 astrophotography, 262 Clark, Alvin, 60 Aurigids, 46 Clavius, Christopher, 82 Aurora, 28–33 Collins, Peter, 158, 217 Auroral Data Center in the US, 29 Coma Berenicids, 50 averted vision, 41 comets, 172–189, 294 azimuth, 67 Arend–Roland, 43 Biela, 49, 68 Baker, Lonny, xxii Bradfield, 69 Barnard, E. E. 111, 181–182 Denning–Fujikawa, 181 Beyer method, estimating comet brightness, Encke, 49, 175 179 Giacobini–Zinner, 48 Beyond the Observatory (Shapley), 35 Halley, 44, 46, 48, 55, 78, 175, 225 big bang, 65 Hartley–IRAS, 175 339 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521797535 - David Levy’s Guide to the Night Sky David H. -

Getting Started with Variable Star Observing

Getting Started with Variable Star Observing The primary types of variable stars you will be observing are: Cepheids - Named after Delta Cephei, these luminous stars brighten and fade with clockwork regularity. There are several types of Cepheids ranging from Beta Cepheids with 0.1 magnitude fluctuations and short periods from 3 to 7 hours to W Virginis Stars with fluctuation of about one magnitude over a period of up to 20 days. In 1910, Henrietta Leavitt learned that the longer a Cepheids period was, the brighter the absolute magnitude was. This led to Harlow Shapely developing the method of using Cepheids to determine the distance to globular clusters and nearby galaxies. Mira Stars - These long period variables are very large red pulsating stars having brightness magnitude ranges of up to 11 magnitudes and a time period from 24 days to 5.7 years. These stars can be regular, semiregular, or irregular. Some examples are Mira 2.0-9.3 332 days, R Leo 5.9 -10.1 313 days, Chi Cygni 3.3-14.2 408 days, Betelgeuse .4- 1.3 5.7 years. Estimates should be done at least twice per month. Eruptive Stars - This group contains Novae and Nova like stars with a great range of types. Recurrent Nova such as T Coronae Borealis may have outbursts that are decades apart. Stars like U Geminorum and SS Cygni repeat their outbursts every few months. One type, R Coronae Borealis, instead of erupting drops by as much as eight magnitudes. UV Ceti stars may flare several magnitudes in a matter of minutes. -

Autumn Sky Tour

Autumn Sky Tour Randy Culp The autumn sky brings some of the faintest constellations carrying the brightest legend - the story of Andromeda and Perseus. With this sky you have the opportunity to tell the story in full, illustrated in spectacular fashion by the stars. While there are many other bright constellations up at this time with interesting features of their own, the Andromeda Legend is the centerpiece of the sky and the backbone of the Autumn Stargazing Tour. The account here is the agenda that I loosely follow in providing a guided tour of the autumn skies as visible from 45° North Latitude. This tour is designed for one topic to lead to the next, so it flows nicely and still manages to teach Astronomy under the night sky as we caravan from one constellation to another. Aside from the binoculars and telescopes I usually make a point of also bringing a highly focused flashlight which serves as an effective pointer for tracing out constellations. Note that this tour is specifically designed to meet requirements 5, 7 and 8 (b) of the Astronomy merit badge, although of course there are lots of other tidbits here that go beyond the requirements of the badge. Updated 16 April 2021 View to the South View to the North Index to the Tour Polar Constellations Down the Milky Way The Zodiac Constellations The Andromeda Legend Perseus the Hero Overview of the Tour I actually start the autumn tour with a quick observation of the Great Square, since you can scarcely move around the sky without stumbling across it. -

Desert Skies – November

Tucson Amateur Astronomy Association Volume LVII, Number 11 November 2011 Last Month’s First Light with the John Zajac 18” Obsession Telescope General Meeting November 4th Steward Observatory Lecture Hall, Room N210 Member’s Night Meeting starts at 6:30pm! Affiliates Desert Skies November 2011 2 Volume LVII, Number 11 TAAA Meeting Friday, November 4 Steward Observatory Lecture Hall, Room N210 6:30pm Title: Members’ Night Theme: Astronomy in Culture & the Arts Van Gogh’s, Starry Night (left) is one of the best The theme for this season’s TAAA Member’s Night is Astronomy representations of astronomy depicted in art. It’s on in Culture & the Arts. Whether its David Bowie’s haunting Space permanent display at the Oddity or Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night, astronomy or more Museum of Modern Art in New precisely the night sky, has inspired a wide range of artists. York City. Artwork adorns many ancient astronomical instruments and some old star charts contain more art than stars. The space age of the 50’s and 60’s, backed by national pride, gave us such things as rocket fins on cars and the space saucer design of the The Flammarion engraving Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). Might it be true that no (right), artist unknown, first other science has this kind of effect on cultures, current or appeared in Flammarion’s 1888 book “The Atmosphere: ancient? Popular Meteorology.” It represents medieval Any member can offer a presentation about this topic. We’ll also cosmology, with a flat earth, have more traditional member’s astronomy presentations about and a solid celestial sphere their astronomy projects. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism. -

04/11/2011 RIA 35 PUBLICACIONES 2007 1. a Portrait of the Nucleus Of

PUBLICACIONES 2007 1. A portrait of the nucleus of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko Author(s): Lamy PL, Toth I, Davidsson BJR, et al. Source: SPACE SCIENCE REVIEWS Volume: 128 Issue: 1-4 Pages: 23-66 Published: 2007 ESA: Hubble ; ROSETTA (on-going studies) 2. Search for tidal dwarf galaxy candidates in a sample of ultraluminous infrared galaxies Author(s): Monreal-Ibero, A; Colina, L; Arribas, S, et al. Source: ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS Volume: 472 Pages: 421-433 Published: 2007 ESA: Hubble; INTEGRAL 3. Supermassive black holes in the Sbc spiral galaxies NGC 3310, NGC 4303 and NGC 4258 Author(s): Pastorini, G; Marconi, A; Capetti, A, et al. Source: ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS Volume: 469 Issue: 2 Pages: 405-U50 Published: JUL 2007 ESA: Hubble 4. HST/ACS observations of shell galaxies: inner shells, shell colours and dust Author(s): Sikkema, G; Carter, D; Peletier, RF, et al. Source: ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS Volume: 467 Issue: 3 Pages: 1011-U27 Published: JUN 2007 ESA: Hubble 5. Optical detection of the radio supernova SN 2000ft in the circumnuclear region of the luminous infrared galaxy NGC 7469 Author(s): Colina, L; Diaz-Santos, T; Alonso-Herrero, A, et al. Source: ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS Volume: 467 Issue: 2 Pages: 559-564 Published: MAY 2007 ESA: Hubble 6. HST and VLT observations of the symbiotic star Hen 2-147 - Its nebular dynamics, its Mira variable and its distance Author(s): Santander-Garcia, M; Corradi, RLM; Whitelock, PA, et al. Source: ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS Volume: 465 Issue: 2 Pages: 481-491 Published: 2007 ESA: Hubble . 04/11/2011 RIA 35 7. Black hole masses and Eddington ratios of AGNs at z < 1: Evidence of retriggering for a representative sample of X-ray-selected AGNs Ballo, L; Cristiani, S; Fasano, G, et al.