Getting Started with Variable Star Observing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathématiques Et Espace

Atelier disciplinaire AD 5 Mathématiques et Espace Anne-Cécile DHERS, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Peggy THILLET, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Yann BARSAMIAN, Education Nationale (mathématiques) Olivier BONNETON, Sciences - U (mathématiques) Cahier d'activités Activité 1 : L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL Activité 2 : DENOMBREMENT D'ETOILES DANS LE CIEL ET L'UNIVERS Activité 3 : D'HIPPARCOS A BENFORD Activité 4 : OBSERVATION STATISTIQUE DES CRATERES LUNAIRES Activité 5 : DIAMETRE DES CRATERES D'IMPACT Activité 6 : LOI DE TITIUS-BODE Activité 7 : MODELISER UNE CONSTELLATION EN 3D Crédits photo : NASA / CNES L'HORIZON TERRESTRE ET SPATIAL (3 ème / 2 nde ) __________________________________________________ OBJECTIF : Détermination de la ligne d'horizon à une altitude donnée. COMPETENCES : ● Utilisation du théorème de Pythagore ● Utilisation de Google Earth pour évaluer des distances à vol d'oiseau ● Recherche personnelle de données REALISATION : Il s'agit ici de mettre en application le théorème de Pythagore mais avec une vision terrestre dans un premier temps suite à un questionnement de l'élève puis dans un second temps de réutiliser la même démarche dans le cadre spatial de la visibilité d'un satellite. Fiche élève ____________________________________________________________________________ 1. Victor Hugo a écrit dans Les Châtiments : "Les horizons aux horizons succèdent […] : on avance toujours, on n’arrive jamais ". Face à la mer, vous voyez l'horizon à perte de vue. Mais "est-ce loin, l'horizon ?". D'après toi, jusqu'à quelle distance peux-tu voir si le temps est clair ? Réponse 1 : " Sans instrument, je peux voir jusqu'à .................. km " Réponse 2 : " Avec une paire de jumelles, je peux voir jusqu'à ............... km " 2. Nous allons maintenant calculer à l'aide du théorème de Pythagore la ligne d'horizon pour une hauteur H donnée. -

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

Sky Notes - April 2012

North Devon Astronomical Society www.northdevonastronomy.co.uk Sky Notes - April 2012 THE MOON New Moon 21s t April First Quarter 29th April Full Moon 6th April Last Quarter 13th April THE PLANETS Mercury A morning object, Mercury is visible before sunrise by the middle of the month. The planet will reach greatest western elongation on the 18th, when it will be around 27 degrees from the Sun. Venus Now moving closer to the Sun once again following greatest elongation last month, but blazing away at magnitude -4.4, Venus still dominates the western evening sky. In the eyepiece, the planet presents a 25 arcsecond disc which is just under half illuminated. Mars Following last month’s opposition, The Red Planet remains fairly close to the bright star Regulus, in the constellation Leo. Though the apparent diameter of the planet will shrink slightly throughout the month, Mars remains worthy of observation and is visible for most of the night. Jupiter Though still visible low in the west after sunset, Jupiter will soon become lost in the evening twilight. Saturn R eaching opposition on the 15th, Saturn is observable all night in the constellation Virgo, close to the first magnitude star Spica, (Alpha Virginis). A magnificent object, Saturn’s rings and it’s largest satellite Titan are readily apparent in small telescopes, while larger instruments will show atmospheric bands and some of the smaller moons. Uranus Ur anus is too close to the Sun to be observable this month. Neptune A morning object, Neptune can be found among the stars of the constellation Aquarius. -

Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Second Edition

RASC Observing Committee Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Second Edition Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Welcome to the Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Program. This program is designed to provide the observer with a well-rounded introduction to the night sky visible from North America. Using this observing program is an excellent way to gain knowledge and experience in astronomy. Experienced observers find that a planned observing session results in a more satisfying and interesting experience. This program will help introduce you to amateur astronomy and prepare you for other more challenging certificate programs such as the Messier and Finest NGC. The program covers the full range of astronomical objects. Here is a summary: Observing Objective Requirement Available Constellations and Bright Stars 12 24 The Moon 16 32 Solar System 5 10 Deep Sky Objects 12 24 Double Stars 10 20 Total 55 110 In each category a choice of objects is provided so that you can begin the certificate at any time of the year. In order to receive your certificate you need to observe a total of 55 of the 110 objects available. Here is a summary of some of the abbreviations used in this program Instrument V – Visual (unaided eye) B – Binocular T – Telescope V/B - Visual/Binocular B/T - Binocular/Telescope Season Season when the object can be best seen in the evening sky between dusk. and midnight. Objects may also be seen in other seasons. Description Brief description of the target object, its common name and other details. Cons Constellation where object can be found (if applicable) BOG Ref Refers to corresponding references in the RASC’s The Beginner’s Observing Guide highlighting this object. -

Plotting Variable Stars on the H-R Diagram Activity

Pulsating Variable Stars and the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram The Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram: The H-R diagram is an important astronomical tool for understanding how stars evolve over time. Stellar evolution can not be studied by observing individual stars as most changes occur over millions and billions of years. Astrophysicists observe numerous stars at various stages in their evolutionary history to determine their changing properties and probable evolutionary tracks across the H-R diagram. The H-R diagram is a scatter graph of stars. When the absolute magnitude (MV) – intrinsic brightness – of stars is plotted against their surface temperature (stellar classification) the stars are not randomly distributed on the graph but are mostly restricted to a few well-defined regions. The stars within the same regions share a common set of characteristics. As the physical characteristics of a star change over its evolutionary history, its position on the H-R diagram The H-R Diagram changes also – so the H-R diagram can also be thought of as a graphical plot of stellar evolution. From the location of a star on the diagram, its luminosity, spectral type, color, temperature, mass, age, chemical composition and evolutionary history are known. Most stars are classified by surface temperature (spectral type) from hottest to coolest as follows: O B A F G K M. These categories are further subdivided into subclasses from hottest (0) to coolest (9). The hottest B stars are B0 and the coolest are B9, followed by spectral type A0. Each major spectral classification is characterized by its own unique spectra. -

NL 2011-2 Backup

Newsletter 2011-3 August 2011 www.variablestarssouth.org Hawkes Bay Astronomical Society members at the site of their partially completed Pukerangi roll-off observatory. Photo by Graham Palmer and provided by Col Bembrick. Col’s recollections of the 2011 RASNZ conference hosted by the Hawkes Bay Astronomical Society appear on page 11. Contents From the director - Tom Richards ........................................................................................................................... 2 Variables from Linden – Towards the Hub - Alan Plummer ................................................................. 4 BL Telescopii - Observations of the 2011 eclipse - Peter F Williams ............................................ 7 A DSLR bright Cepheid project - Can you help? - Stan Walker ........................................................ 9 RASNZ Conference Napier, 2011 - Col Bembrick ................................................................................... 11 Recurrent Novae - Stan Walker .............................................................................................................................. 13 Southern Binaries DSLR Project - Mark Blackford .................................................................................. 17 Equatorial Eclipsing Binaries Project - Tom Richards ............................................................................ 19 SPADES Report - Tom Richards ........................................................................................................................... -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

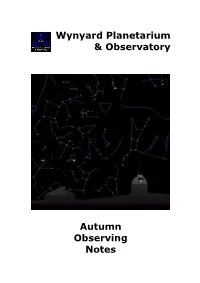

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

The Heavens in August a Study of Short Period Variables

100 SCIENTIFIC,AMERlCAN July 31, 1915 The Heavens in August A Study of Short Period Variables By Prof. Henry Norris Russell, Ph.D. HE warm clear nights of summer offer the amateur which is marked on our map, .and the second lies about and but 18 minutes of arc apart, while Neptune is only T the best chance for star-gazing in all the year, and, two fifths of the way from this to () Ophiuchi (also a degree away on the other side. This simultaneous fortunately, he has one of the finest portions of the shown on the map) and is the only bright star near conjunction of three planets is rather remarkable, but, heavens at his command in the splendid region of the this line. The character of the variation is in both as they rise less than an hour earlier than the Sun, Milky Way, which stretches from Cassiopeia and cases very similar to that of the stars previously de Neptune will be utterly invisible, though the other two Cygnus through Aquila to Sagittarius and Scorpio, and scribed. w Sagittarii varies from magnitude 4.3 to 5.1 planets may easily be seen with a telescope (provided forms a vast circle right across the summit of the vault in a period of 7.595 days, the ris� in brightness taking with suitable finding circles ) even in broad daylight, of heaven. about half as long as the fall, and the maximum being and in the same low-power field. The veriest novice can learn in an hour to identify a little more than twice the minimum light. -

Dramatic Change in the Boundary Layer in the Symbiotic Recurrent

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. tcrb˙submitted˙to˙arxiv © ESO 2018 July 4, 2018 Dramatic change in the boundary layer in the symbiotic recurrent nova T Coronae Borealis. G. J. M. Luna,1,2,3, K. Mukai,4,5 J. L. Sokoloski,6 T. Nelson,7 P. Kuin,8 A. Segreto,9 G. Cusumano,9 M. Jaque Arancibia,10,11 and N. E. Nu˜nez,11 1 CONICET-Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Astronom´ıa y F´ısica del Espacio, (IAFE), Av. Inte. G¨uiraldes 2620, C1428ZAA, Buenos Aires, Argentina e-mail: [email protected] 2 Universidad de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Buenos Aires, Argentina 3 Universidad Nacional Arturo Jauretche, Av. Calchaqu´ı6200, F. Varela, Buenos Aires, Argentina 4 CRESST and X-ray Astrophysics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 5 Department of Physics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA 6 Columbia Astrophysics Lab 550 W120th St., 1027 Pupin Hall, MC 5247 Columbia University, New York, New York 10027, USA 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 8 University College London, Mullard Space Science Laboratory, Holmbury St. Mary, Dorking, RH5 6NT, U.K. 9 INAF - Istituto di Astrofisica Spaziale e Fisica Cosmica, Via U. La Malfa 153, I-90146 Palermo, Italy 10 Departamento de F´ısica y Astronom´ıa, Universidad de La Serena, Av. Cisternas 1200, La Serena, Chile. 11 Instituto de Ciencias Astron´omicas, de la Tierra y del Espacio (ICATE-CONICET), Av. Espa˜na Sur 1512, J5402DSP, San Juan, Argentina ABSTRACT A sudden increase in the rate at which material reaches the most internal part of an accretion disk, i.e. -

Fy10 Budget by Program

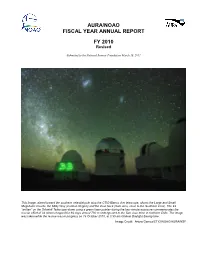

AURA/NOAO FISCAL YEAR ANNUAL REPORT FY 2010 Revised Submitted to the National Science Foundation March 16, 2011 This image, aimed toward the southern celestial pole atop the CTIO Blanco 4-m telescope, shows the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, the Milky Way (Carinae Region) and the Coal Sack (dark area, close to the Southern Crux). The 33 “written” on the Schmidt Telescope dome using a green laser pointer during the two-minute exposure commemorates the rescue effort of 33 miners trapped for 69 days almost 700 m underground in the San Jose mine in northern Chile. The image was taken while the rescue was in progress on 13 October 2010, at 3:30 am Chilean Daylight Saving time. Image Credit: Arturo Gomez/CTIO/NOAO/AURA/NSF National Optical Astronomy Observatory Fiscal Year Annual Report for FY 2010 Revised (October 1, 2009 – September 30, 2010) Submitted to the National Science Foundation Pursuant to Cooperative Support Agreement No. AST-0950945 March 16, 2011 Table of Contents MISSION SYNOPSIS ............................................................................................................ IV 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 1 2 NOAO ACCOMPLISHMENTS ....................................................................................... 2 2.1 Achievements ..................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Status of Vision and Goals ................................................................................ -

Abstract a Search for Extrasolar Planets Using Echoes Produced in Flare Events

ABSTRACT A SEARCH FOR EXTRASOLAR PLANETS USING ECHOES PRODUCED IN FLARE EVENTS A detection technique for searching for extrasolar planets using stellar flare events is explored, including a discussion of potential benefits, potential problems, and limitations of the method. The detection technique analyzes the observed time versus intensity profile of a star’s energetic flare to determine possible existence of a nearby planet. When measuring the pulse of light produced by a flare, the detection of an echo may indicate the presence of a nearby reflective surface. The flare, acting much like the pulse in a radar system, would give information about the location and relative size of the planet. This method of detection has the potential to give science a new tool with which to further humankind’s understanding of planetary systems. Randal Eugene Clark May 2009 A SEARCH FOR EXTRASOLAR PLANETS USING ECHOES PRODUCED IN FLARE EVENTS by Randal Eugene Clark A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Physics in the College of Science and Mathematics California State University, Fresno May 2009 © 2009 Randal Eugene Clark APPROVED For the Department of Physics: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Randal Eugene Clark Thesis Author Fred Ringwald (Chair) Physics Karl Runde Physics Ray Hall Physics For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship.