Carbonyl Stress in Bacteria: Causes and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electron Transport Phosphorylation in Rumen Butyrivibrios: Unprecedented ATP Yield for Glucose Fermentation to Butyrate

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY published: 24 June 2015 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00622 Electron transport phosphorylation in rumen butyrivibrios: unprecedented ATP yield for glucose fermentation to butyrate Timothy J. Hackmann1 and Jeffrey L. Firkins2* 1 Department of Animal Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA, 2 Department of Animal Sciences, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA From a genomic analysis of rumen butyrivibrios (Butyrivibrio and Pseudobutyrivibrio sp.), we have re-evaluated the contribution of electron transport phosphorylation (ETP) to ATP formation in this group. This group is unique in that most (76%) genomes were predicted to possess genes for both Ech and Rnf transmembrane ion pumps. These pumps act in concert with the NifJ and Bcd-Etf to form a electrochemical potential (μH+ and μNa+), which drives ATP synthesis by ETP. Of the 62 total butyrivibrio genomes currently available from the Hungate 1000 project, all 62 were predicted to Edited by: possess NifJ, which reduces oxidized ferredoxin (Fdox) during pyruvate conversion to Emilio M. Ungerfeld, Instituto de Investigaciones acetyl-CoA. All 62 possessed all subunits of Bcd-Etf, which reduces Fdox and oxidizes Agropecuarias, Chile reduced NAD during crotonyl-CoA reduction. Additionally, 61 genomes possessed all Reviewed by: subunits of the Rnf, which generates μH+ or μNa+ from oxidation of reduced Fd Wolfgang Buckel, (Fdred) and reduction of oxidized NAD. Further, 47 genomes possessed all six subunits Philipps-Universität Marburg, + Germany of the Ech, which generates μH from oxidation of Fdred. For glucose fermentation Robert J. Wallace, to butyrate and H2, the electrochemical potential established should drive synthesis University of Aberdeen, UK of ∼1.5 ATP by the F0F1-ATP synthase (possessed by all 62 genomes). -

Supplementary Informations SI2. Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Informations SI2. Supplementary Table 1. M9, soil, and rhizosphere media composition. LB in Compound Name Exchange Reaction LB in soil LBin M9 rhizosphere H2O EX_cpd00001_e0 -15 -15 -10 O2 EX_cpd00007_e0 -15 -15 -10 Phosphate EX_cpd00009_e0 -15 -15 -10 CO2 EX_cpd00011_e0 -15 -15 0 Ammonia EX_cpd00013_e0 -7.5 -7.5 -10 L-glutamate EX_cpd00023_e0 0 -0.0283302 0 D-glucose EX_cpd00027_e0 -0.61972444 -0.04098397 0 Mn2 EX_cpd00030_e0 -15 -15 -10 Glycine EX_cpd00033_e0 -0.0068175 -0.00693094 0 Zn2 EX_cpd00034_e0 -15 -15 -10 L-alanine EX_cpd00035_e0 -0.02780553 -0.00823049 0 Succinate EX_cpd00036_e0 -0.0056245 -0.12240603 0 L-lysine EX_cpd00039_e0 0 -10 0 L-aspartate EX_cpd00041_e0 0 -0.03205557 0 Sulfate EX_cpd00048_e0 -15 -15 -10 L-arginine EX_cpd00051_e0 -0.0068175 -0.00948672 0 L-serine EX_cpd00054_e0 0 -0.01004986 0 Cu2+ EX_cpd00058_e0 -15 -15 -10 Ca2+ EX_cpd00063_e0 -15 -100 -10 L-ornithine EX_cpd00064_e0 -0.0068175 -0.00831712 0 H+ EX_cpd00067_e0 -15 -15 -10 L-tyrosine EX_cpd00069_e0 -0.0068175 -0.00233919 0 Sucrose EX_cpd00076_e0 0 -0.02049199 0 L-cysteine EX_cpd00084_e0 -0.0068175 0 0 Cl- EX_cpd00099_e0 -15 -15 -10 Glycerol EX_cpd00100_e0 0 0 -10 Biotin EX_cpd00104_e0 -15 -15 0 D-ribose EX_cpd00105_e0 -0.01862144 0 0 L-leucine EX_cpd00107_e0 -0.03596182 -0.00303228 0 D-galactose EX_cpd00108_e0 -0.25290619 -0.18317325 0 L-histidine EX_cpd00119_e0 -0.0068175 -0.00506825 0 L-proline EX_cpd00129_e0 -0.01102953 0 0 L-malate EX_cpd00130_e0 -0.03649016 -0.79413596 0 D-mannose EX_cpd00138_e0 -0.2540567 -0.05436649 0 Co2 EX_cpd00149_e0 -

Phyre 2 Results for P25553

Email [email protected] Description P25553 Thu Jan 5 11:42:11 GMT Date 2012 Unique Job 5024f4b9e5342484 ID Detailed template information # Template Alignment Coverage 3D Model Confidence % i.d. Template Information PDB header:oxidoreductase 1 c2hg2A_ Alignment 100.0 100 Chain: A: PDB Molecule:aldehyde dehydrogenase a; PDBTitle: structure of lactaldehyde dehydrogenase PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: B: PDB Molecule:betaine aldehyde dehydrogenase; 2 c3ed6B_ 100.0 36 Alignment PDBTitle: 1.7 angstrom resolution crystal structure of betaine aldehyde2 dehydrogenase (betb) from staphylococcus aureus PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: A: PDB Molecule:formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase; 3 c2o2qA_ 100.0 33 Alignment PDBTitle: crystal structure of the c-terminal domain of rat2 10'formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase in complex with nadp Fold:ALDH-like 4 d1a4sa_ Alignment 100.0 35 Superfamily:ALDH-like Family:ALDH-like PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: H: PDB Molecule:succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 5 c3ifgH_ Alignment 100.0 34 (nadp+); PDBTitle: crystal structure of succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase from2 burkholderia pseudomallei, part 1 of 2 Fold:ALDH-like 6 d1bxsa_ Alignment 100.0 33 Superfamily:ALDH-like Family:ALDH-like Fold:ALDH-like 7 d1o9ja_ Alignment 100.0 33 Superfamily:ALDH-like Family:ALDH-like PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: A: PDB Molecule:succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 8 c3rh9A_ Alignment 100.0 35 (nad(p)(+)); PDBTitle: the crystal structure of oxidoreductase from marinobacter aquaeolei PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: B: PDB Molecule:5-carboxymethyl-2-hydroxymuconate 9 c2d4eB_ Alignment 100.0 32 semialdehyde PDBTitle: crystal structure of the hpcc from thermus thermophilus hb8 PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: G: PDB Molecule:antiquitin; 10 c2jg7G_ 100.0 28 Alignment PDBTitle: crystal structure of seabream antiquitin and elucidation of2 its substrate specificity PDB header:oxidoreductase Chain: C: PDB Molecule:succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase 11 c3jz4C_ 100.0 39 Alignment [nadp+]; PDBTitle: crystal structure of e. -

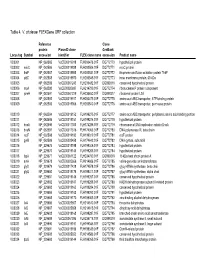

Table 4. V. Cholerae Flexgene ORF Collection

Table 4. V. cholerae FLEXGene ORF collection Reference Clone protein PlasmID clone GenBank Locus tag Symbol accession identifier FLEX clone name accession Product name VC0001 NP_062585 VcCD00019918 FLH200476.01F DQ772770 hypothetical protein VC0002 mioC NP_062586 VcCD00019938 FLH200506.01F DQ772771 mioC protein VC0003 thdF NP_062587 VcCD00019958 FLH200531.01F DQ772772 thiophene and furan oxidation protein ThdF VC0004 yidC NP_062588 VcCD00019970 FLH200545.01F DQ772773 inner membrane protein, 60 kDa VC0005 NP_062589 VcCD00061243 FLH236482.01F DQ899316 conserved hypothetical protein VC0006 rnpA NP_062590 VcCD00025697 FLH214799.01F DQ772774 ribonuclease P protein component VC0007 rpmH NP_062591 VcCD00061229 FLH236450.01F DQ899317 ribosomal protein L34 VC0008 NP_062592 VcCD00019917 FLH200475.01F DQ772775 amino acid ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein VC0009 NP_062593 VcCD00019966 FLH200540.01F DQ772776 amino acid ABC transproter, permease protein VC0010 NP_062594 VcCD00019152 FLH199275.01F DQ772777 amino acid ABC transporter, periplasmic amino acid-binding portion VC0011 NP_062595 VcCD00019151 FLH199274.01F DQ772778 hypothetical protein VC0012 dnaA NP_062596 VcCD00017363 FLH174286.01F DQ772779 chromosomal DNA replication initiator DnaA VC0013 dnaN NP_062597 VcCD00017316 FLH174063.01F DQ772780 DNA polymerase III, beta chain VC0014 recF NP_062598 VcCD00019182 FLH199319.01F DQ772781 recF protein VC0015 gyrB NP_062599 VcCD00025458 FLH174642.01F DQ772782 DNA gyrase, subunit B VC0016 NP_229675 VcCD00019198 FLH199346.01F DQ772783 hypothetical protein -

Fermentation of Dihydroxyacetone by Engineered Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella Variicola to Products

Fermentation of dihydroxyacetone by engineered Escherichia coli and Klebsiella variicola to products Liang Wanga, Diane Chauliaca,1, Mun Su Rheea,2, Anushadevi Panneerselvama, Lonnie O. Ingrama,3, and K. T. Shanmugama,3 aDepartment of Microbiology and Cell Science, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611 Contributed by Lonnie O. Ingram, March 21, 2018 (sent for review January 18, 2018; reviewed by John W. Frost and F. Robert Tabita) Methane can be converted to triose dihydroxyacetone (DHA) by process, formaldehyde can also be produced biologically from chemical processes with formaldehyde as an intermediate. Carbon CO2 with formate as an intermediate (Fig. 1) (7). Dickens and dioxide, a by-product of various industries including ethanol/ Williamson reported as early as 1958 that DHA can be produced butanol biorefineries, can also be converted to formaldehyde biologically by transketolation of hydroxypyruvate and formalde- and then to DHA. DHA, upon entry into a cell and phosphorylation hyde (8). This transketolase is implicated in a unique pentose– to DHA-3-phosphate, enters the glycolytic pathway and can be phosphate–dependent pathway (DHA cycle) in methanol-utilizing fermented to any one of several products. However, DHA is yeast that fixes formaldehyde to xylulose-5-phosphate, yielding inhibitory to microbes due to its chemical interaction with cellular DHA as an intermediate in the production of glyceraldehyde-3- components. Fermentation of DHA to D-lactate by Escherichia coli phosphate in a cyclic mode (9). DHA in the cytoplasm is phos- strain TG113 was inefficient, and growth was inhibited by 30 g·L−1 phorylated by DHA kinase and/or glycerol kinase, and the DHA-P DHA. -

Viewed and Published Immediately Upon Acceptance Cited in Pubmed and Archived on Pubmed Central Yours — You Keep the Copyright

BMC Bioinformatics BioMed Central Methodology article Open Access Optimization based automated curation of metabolic reconstructions Vinay Satish Kumar1, Madhukar S Dasika2 and Costas D Maranas*2 Address: 1Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA and 2Department of Chemical Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA Email: Vinay Satish Kumar - [email protected]; Madhukar S Dasika - [email protected]; Costas D Maranas* - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 20 June 2007 Received: 14 December 2006 Accepted: 20 June 2007 BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8:212 doi:10.1186/1471-2105-8-212 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2105/8/212 © 2007 Satish Kumar et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: Currently, there exists tens of different microbial and eukaryotic metabolic reconstructions (e.g., Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Bacillus subtilis) with many more under development. All of these reconstructions are inherently incomplete with some functionalities missing due to the lack of experimental and/or homology information. A key challenge in the automated generation of genome-scale reconstructions is the elucidation of these gaps and the subsequent generation of hypotheses to bridge them. Results: In this work, an optimization based procedure is proposed to identify and eliminate network gaps in these reconstructions. First we identify the metabolites in the metabolic network reconstruction which cannot be produced under any uptake conditions and subsequently we identify the reactions from a customized multi-organism database that restores the connectivity of these metabolites to the parent network using four mechanisms. -

Protein Glycation and Methylglyoxal Metabolism in Parkinson's Disease

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE QUÍMICA E BIOQUÍMICA Protein glycation and methylglyoxal metabolism in Parkinson’s disease Hugo Miguel Vicente Miranda Doutoramento em Bioquímica (Especialidade: Regulação Bioquímica) 2009 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS DEPARTAMENTO DE QUÍMICA E BIOQUÍMICA Protein glycation and methylglyoxal metabolism in Parkinson’s disease Hugo Miguel Vicente Miranda Doutoramento em Bioquímica (Especialidade: Regulação Bioquímica) Tese orientada pelo Doutor Carlos Alberto Alves Cordeiro e pelo Prof. Doutor Alexandre Luís de Matos Botica Cortês Quintas 2009 De acordo com o disposto no artigo n°. 40 do Regulamento de Estudos Pós-Graduados da Universidade de Lisboa, Deliberação n° 961/2003, publicada no Diário da República – II Série n°. 153 – 5 de Julho de 2003, foram incluídos nesta dissertação os resultados dos seguintes artigos: Gomes RA, Sousa Silva M, Vicente Miranda H, Ferreira AEN, Cordeiro C, Ponces Freire A. 2005. Protein glycation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Argpyrimidine formation and methylglyoxal catabolism. FEBS J. 272: 4521-4531. Gomes RA, Vicente Miranda H, Sousa Silva M, Graça G, Coelho AV, Ferreira AEN, Cordeiro C, Ponces Freire A. 2006. Yeast protein glycation in vivo by methylglyoxal: Molecular modification of glycolytic enzymes and heat shock proteins. FEBS J. 273: 5273-5287. Vicente Miranda H, Ferreira AEN, Cordeiro C, Ponces Freire A. 2006. Kinetic assay for measurement of enzyme concentration in situ. Anal Biochem 354: 148-150. Vicente Miranda H, Ferreira AEN, Quintas A, Cordeiro C, Ponces Freire A. 2008. Measuring intracellular enzyme concentrations. BAMBED 36(2): 135-138. Gomes RA, Vicente Miranda H, Sousa Silva M, Graça G, Coelho AV, Ferreira AEN, Cordeiro C, Ponces Freire A. -

A Universal Tradeoff Between Growth and Lag in Fluctuating Environments

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Nature. Manuscript Author Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2021 January 15. Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2020 August ; 584(7821): 470–474. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2505-4. A universal tradeoff between growth and lag in fluctuating environments Markus Basan1,2,¶,*, Tomoya Honda3,4,*, Dimitris Christodoulou2, Manuel Hörl2, Yu-Fang Chang1, Emanuele Leoncini1, Avik Mukherjee1, Hiroyuki Okano3, Brian R. Taylor3, Josh M. Silverman5, Carlos Sanchez1, James R. Williamson5, Johan Paulsson1, Terence Hwa3,4,¶, Uwe Sauer2,¶ 1Department of Systems Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA. 2Institute of Molecular Systems Biology, ETH Zürich, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland. 3Department of Physics, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 USA. 4Section of Molecular Biology, Division of Biological Sciences, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 USA. 5Department of Integrative Structural and Computational Biology, and The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. Abstract The rate of cell growth is crucial for bacterial fitness and a main driver of proteome allocation1,2, but it is unclear what ultimately determines growth rates in different environmental conditions. Increasing evidence suggests that other objectives also play key roles3–7, such as the rate of physiological adaptation to changing environments8,9. The challenge for cells is that these objectives often cannot be independently optimized, and maximizing one often reduces another. Many such tradeoffs have indeed been hypothesized, based on qualitative correlative studies8–11. Here we report the occurrence of a tradeoff between steady-state growth rate and physiological adaptability for Escherichia coli, upon abruptly shifting a growing culture from a preferred carbon source to fermentation products such as acetate. -

Supplemental Table S1: Comparison of the Deleted Genes in the Genome-Reduced Strains

Supplemental Table S1: Comparison of the deleted genes in the genome-reduced strains Legend 1 Locus tag according to the reference genome sequence of B. subtilis 168 (NC_000964) Genes highlighted in blue have been deleted from the respective strains Genes highlighted in green have been inserted into the indicated strain, they are present in all following strains Regions highlighted in red could not be deleted as a unit Regions highlighted in orange were not deleted in the genome-reduced strains since their deletion resulted in severe growth defects Gene BSU_number 1 Function ∆6 IIG-Bs27-47-24 PG10 PS38 dnaA BSU00010 replication initiation protein dnaN BSU00020 DNA polymerase III (beta subunit), beta clamp yaaA BSU00030 unknown recF BSU00040 repair, recombination remB BSU00050 involved in the activation of biofilm matrix biosynthetic operons gyrB BSU00060 DNA-Gyrase (subunit B) gyrA BSU00070 DNA-Gyrase (subunit A) rrnO-16S- trnO-Ala- trnO-Ile- rrnO-23S- rrnO-5S yaaC BSU00080 unknown guaB BSU00090 IMP dehydrogenase dacA BSU00100 penicillin-binding protein 5*, D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase pdxS BSU00110 pyridoxal-5'-phosphate synthase (synthase domain) pdxT BSU00120 pyridoxal-5'-phosphate synthase (glutaminase domain) serS BSU00130 seryl-tRNA-synthetase trnSL-Ser1 dck BSU00140 deoxyadenosin/deoxycytidine kinase dgk BSU00150 deoxyguanosine kinase yaaH BSU00160 general stress protein, survival of ethanol stress, SafA-dependent spore coat yaaI BSU00170 general stress protein, similar to isochorismatase yaaJ BSU00180 tRNA specific adenosine -

12) United States Patent (10

US007635572B2 (12) UnitedO States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,635,572 B2 Zhou et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 22, 2009 (54) METHODS FOR CONDUCTING ASSAYS FOR 5,506,121 A 4/1996 Skerra et al. ENZYME ACTIVITY ON PROTEIN 5,510,270 A 4/1996 Fodor et al. MICROARRAYS 5,512,492 A 4/1996 Herron et al. 5,516,635 A 5/1996 Ekins et al. (75) Inventors: Fang X. Zhou, New Haven, CT (US); 5,532,128 A 7/1996 Eggers Barry Schweitzer, Cheshire, CT (US) 5,538,897 A 7/1996 Yates, III et al. s s 5,541,070 A 7/1996 Kauvar (73) Assignee: Life Technologies Corporation, .. S.E. al Carlsbad, CA (US) 5,585,069 A 12/1996 Zanzucchi et al. 5,585,639 A 12/1996 Dorsel et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,593,838 A 1/1997 Zanzucchi et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,605,662 A 2f1997 Heller et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,620,850 A 4/1997 Bamdad et al. 5,624,711 A 4/1997 Sundberg et al. (21) Appl. No.: 10/865,431 5,627,369 A 5/1997 Vestal et al. 5,629,213 A 5/1997 Kornguth et al. (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2005/O118665 A1 Jun. 2, 2005 EP 596421 10, 1993 EP 0619321 12/1994 (51) Int. Cl. EP O664452 7, 1995 CI2O 1/50 (2006.01) EP O818467 1, 1998 (52) U.S. -

Fluoroacetate Resistance in Streptomyces Cattleya 3.1 Introduction 41 3.2 Materials and Methods 42 3.3 Results and Discussion 47 3.4 Conclusions 66 3.5 References 67

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Expanding the scope of organofluorine biochemistry through the study of natural and engineered systems Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9n89c8zv Author Walker, Mark Chalfant Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Expanding the scope of organofluorine biochemistry through the study of natural and engineered systems by Mark Chalfant Walker A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular and Cell Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michelle C. Y. Chang, Chair Professor Judith P. Klinman Professor Susan Marqusee Professor Mathew B. Francis Spring 2013 Expanding the scope of organofluorine biochemistry through the study of natural and engineered systems © 2013 by Mark Chalfant Walker Abstract Expanding the scope of organofluorine biochemistry through the study of natural and engineered systems by Mark Chalfant Walker Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular and Cell Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Michelle C. Y. Chang, Chair Fluorination has become a very useful tool in the design and optimization of bioactive small molecules ranging from pesticides to pharmaceuticals. Its small size allows a sterically conservative substitution for a hydrogen or hydroxyl, thus maintaining the overall size and shape of a molecule. However, the extreme electronegativity of fluorine can dramatically alter other properties of the molecule. As a result, the development of new methods for fluorine incorporation is currently a major focus in synthetic chemistry. It is our goal to use a complementary biosynthetic approach to use enzymes for the regio-selective incorporation of fluorine into complex natural product scaffolds through the fluoroacetate building block. -

Table 4.3 Enzyme Activities and Glycerol Utilization and Ethanol Synthesis Fluxes for Wild-Type MG1655 and Strains Overexpressing Glycerol Utilization Enzymes

Abstract Understanding Fermentative Glycerol Metabolism and its Application for the Production of Fuels and Chemicals by James M. Clomburg Due to its availability, low-price, and higher degree of reduction than lignocellulosic sugars, glycerol has become an attractive carbon source for the production of fuels and reduced chemicals. However, this high degree of reduction of carbon atoms in glycerol also results in significant challenges in regard to its utilization under fermentative conditions. Therefore, in order to unlock the full potential of microorganisms for the fermentative conversion of glycerol into fuels and chemicals, a detailed understanding of the anaerobic fermentation of glycerol is required. The work presented here highlights a comprehensive experimental investigation into fermentative glycerol metabolism in Escherichia coli, which has elucidated several key pathways and mechanisms. The activity of both the fermentative and respiratory glycerol dissimilation pathways was found to be important for maximum glycerol utilization, a consequence of the metabolic cycle and downstream effects created by the essential involvement of PEP-dependent dihydroxyacetone kinase (DHAK) in the fermentative glycerol dissimilation pathway. The decoupling of this cycle is of central importance during fermentative glycerol metabolism, and while multiple decoupling mechanisms were identified, their relative inefficiencies dictated not only their level of involvement, but also iii implicated the activity of other pathways/enzymes, including fumarate reductase and pyruvate kinase. The central role of the PEP-dependent DHAK, an enzyme whose transcription was found to be regulated by the cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP)-cAMP complex, was also tied to the importance of multiple fructose 1,6-bisphosphotases (FBPases) encoded by fbp, glpX, and yggF.