Downloaded from Pubfactory at 09/25/2021 11:10:39PM Via Free Access 158 Torben R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saxon Queen Discovered in Germany 20 January 2010

Saxon queen discovered in Germany 20 January 2010 skeleton aged between 30 and 40 was found, wrapped in silk. Dr Harald Meller of the Landesmuseum fur Vorgeschichte in Saxony Anhalt, who led the project, said: “We still are not completely certain that this is Eadgyth, although all the scientific evidence points to this interpretation. In the Middle Ages, bones were moved around as relics and this makes definitive identification difficult.” As part of the research project, some small samples are being brought to the University of The raising of the tomb's lid. Photo by the State Office Bristol for further analysis. for Heritage Management and Archaeology, Saxony- Anhalt The research group at Bristol will be hoping to trace the isotopes in these bones to provide a geographical signature that matches where Eadgyth is likely to have grown up. (PhysOrg.com) -- Remains of one of the oldest members of the English royal family have been Professor Mark Horton of the Department of unearthed at Magdeburg Cathedral in Germany. Archaeology and Anthropology, who is co- The preliminary findings will be announced at a ordinating this side of the research, explained the conference at the University of Bristol today. strategy: “We know that Saxon royalty moved around quite a lot, and we hope to match the Eadgyth, the sister of King Athelstan and the isotope results with known locations around granddaughter of Alfred the Great, was given in Wessex and Mercia, where she could have spent marriage to Otto I, the Holy Roman Emperor, in her childhood. If we can prove this truly is Eadgyth, 929. -

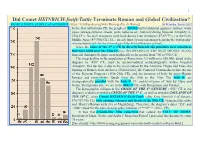

Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: G

1 Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demografia_di_Roma] G. Heinsohn, January 2021 In the first millennium CE, the people of ROME built residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc., but only during Imperial Antiquity (1- 230s CE). No such structures were built during Late Antiquity (4th-6th/7th c.) or the Early Middle Ages (8th-930s CE). [See already https://q-mag.org/gunnar-heinsohn-the-stratigraphy- of-rome-benchmark-for-the-chronology-of-the-first-millennium-ce.html] Since the ruins of the 3rd c. CE lie directly beneath the primitive new structures that were built after the 930s CE (i.e., BEGINNING OF THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES), Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from 700 to 930s CE. The steep decline in the population of Rome from 1.5 million to 650,000, dated in the diagram to "450" CE, must be accommodated archaeologically within Imperial Antiquity. This decline is due to the crisis caused by the Antonine Plague and Fires, the burning of Rome's State Archives (Tabularium), the Comet of Commodus before the rise of the Severan Emperors (190s-230s CE), and the invasion of Italy by proto-Hunnic Iazyges and proto-Gothic Quadi from the 160s to the 190s. The 160s ff. are stratigraphically parallel with the 450s ff. CE and its invasion of Italy by Huns and Goths. Stratigraphically, we are in the 860s ff. CE, with Hungarians and Vikings. The demographic collapse in the CRISIS OF THE 6th CENTURY (“553” CE in the diagram) is identical with the CRISIS OF THE 3rd C., as well as with the COLLAPSE OF THE 10th C., when Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle (after King Heinrich I of Saxony; 876/919-936 CE) with ensuing volcanos and floods of the 930s CE ) damaged the globe and Henry’s Roman style city of Magdeburg). -

English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep

Outline--English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep. Page 1 ANGLO-SAXON CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY IN BRIEF SOURCES 1. Narrative history: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Bede died 735); the Anglo- Saxon Chronicle (late 9th to mid-12th centuries); Gildas, On the Downfall and Conquest of Britain (1st half of 6th century). 2. The so-called “law codes,” beginning with Æthelberht (c. 600) and going right up through Cnut (d. 1035). 3. Language and literature: Beowulf, lyric poetry, translations of pieces of the Bible, sermons, saints’ lives, medical treatises, riddles, prayers 4. Place-names; geographical features 5. Coins 6. Art and archaeology 7. Charters BASIC CHRONOLOGY 1. The main chronological periods (Mats. p. II–1): ?450–600 — The invasions to Æthelberht of Kent Outline--English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep. Page 2 600–835 — (A healthy chunk of time here; the same amount of time that the United States has been in existence.) The period of the Heptarchy—overlordships moving from Northumbria to Mercia to Wessex. 835–924 — The Danish Invasions. 924–1066 — The kingdom of England ending with the Norman Conquest. 2. The period of the invasions (Bede on the origins of the English settlers) (Mats. p. II–1), 450–600 They came from three very powerful nations of the Germans, namely the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes. From the stock of the Jutes are the people of Kent and the people of Wight, that is, the race which holds the Isle of Wight, and that which in the province of the West Saxons is to this day called the nation of the Jutes, situated opposite that same Isle of Wight. -

British Royal Ancestry Book 6, Kings of England from King Alfred the Great to Present Time

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY BRITISH ROYAL ANCESTRY, BOOK 6 Kings of England INTRODUCTION The British ancestry is very much a patchwork of various beginnings. Until King Alfred the Great established England various Kings ruled separate parts. In most cases the initial ruler came from the mainland. That time of the history is shrouded in myths, which turn into legends and subsequent into history. Alfred the Great (849-901) was a very learned man and studied all available past history and especially biblical information. He came up with the concept that he was the 72nd generation descendant of Adam and Eve. Moreover he was a 17th generation descendant of Woden (Odin). Proponents of one theory claim that he was the descendant of Noah’s son Sem (Shem) because he claimed to descend from Sceaf, a marooned man who came to Britain on a boat after a flood. (See the Biblical Ancestry and Early Mythology Ancestry books). The book British Mythical Royal Ancestry from King Brutus shows the mythical kings including Shakespeare’s King Lair. The lineages are from a common ancestor, Priam King of Troy. His one daughter Troana leads to us via Sceaf, the descendants from his other daughter Creusa lead to the British linage. No attempt has been made to connect these rulers with the historical ones. Before Alfred the Great formed a unified England several Royal Houses ruled the various parts. Not all of them have any clear lineages to the present times, i.e. our ancestors, but some do. I have collected information which shows these. They include; British Royal Ancestry Book 1, Legendary Kings from Brutus of Troy to including King Leir. -

Deeds of the Saxons 1St Edition Kindle

DEEDS OF THE SAXONS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bernard Bachrach | 9780813226934 | | | | | Deeds of the Saxons 1st edition PDF Book Ironically, it is precisely in the preface to each book, including this one, that Widukind demonstrates his rhetorical skills, and potentially runs the risk of having his language be judged excessive, i. Whether you're a budding rare book collector or a bibliophile with an evniable collection, discover an amazing selection of rare and collectible books from booksellers around the world. They draw on a large number of other written sources of information, including both narrative works and the political, economic, social, and military affairs of the day, and provide an extensive apparatus of notes. LOG IN. The contexts and dates of the various versions which these represent have occasioned much discussion. Deeds of the Saxons. Preface p. Roman Reflections uses a series of detailed and deeply researched case studies to explore how Roman society connected with and influenced Northern Europe during the Iron and Viking Ages. The Franks get the help of the newly immigrated Saxons who are looking for land, and a bloody battle is fought at Scithingi. PleWidukind, a monk at the prominent monastery of Corvey in Saxony during the middle third of the tenth century, is known to posterity through his Res gestae Saxonicae, an exceptionally rich account of the Saxon people and the reigns of the first two rulers of the Ottonian dynasty, Henry I. Book Two pp. These are the patron saints of the monastery of Corvey. Simplified Ottonian Dynastic Genealogy p. Roman Reflections. -

St. Matilda Feast: March 14

St. Matilda Feast: March 14 Facts Feast Day: March 14 Matilda was the daughter of Count Dietrich of Westphalia and Reinhild of Denmark. She was also known as Mechtildis and Maud. She was raised by her grandmother, the Abbess of Eufurt convent. Matilda married Henry the Fowler, son of Duke Otto of Saxony, in the year 909. He succeeded his father as Duke in the year 912 and in 919 succeeded King Conrad I to the German throne. She was noted for her piety and charitable works. She was widowed in the year 936, and supported her son Henry's claim to his father's throne. When her son Otto (the Great) was elected, she persuaded him to name Henry Duke of Bavaria after he had led an unsuccessful revolt. She was severely criticized by both Otto and Henry for what they considered her extravagant charities. She resigned her inheritance to her sons, and retired to her country home but was called to the court through the intercession of Otto's wife, Edith. When Henry again revolted, Otto put down the insurrection in the year 941 with great cruelty. Matilda censored Henry when he began another revolt against Otto in the year 953 and for his ruthlessness in suppressing a revolt by his own subjects; at that time she prophesized his imminent death. When he did die in 955, she devoted herself to building three convents and a monastery, was left in charge of the kingdom when Otto went to Rome in 962 to be crowned Emperor (often regarded as the beginning of the Holy Roman Empire), and spent most of the declining years of her life at the convent at Nordhausen she had built. -

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A)

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A) David K. Faux The goal of the present work is to assemble widely scattered facts to accurately record the story of one of Europe’s most enigmatic people of the early historic era – the Cimbri. To meet this goal, the present study will trace the antecedents and descendants of the Cimbri, who reside or resided in the northern part of the Jutland Peninsula, in what is today known as the County of Himmerland, Denmark. It is likely that the name Cimbri came to represent the peoples of the Cimbric Peninsula and nearby islands, now called Jutland, Fyn and so on. Very early (3rd Century BC) Greek sources also make note of the Teutones, a tribe closely associated with the Cimbri, however their specific place of residence is not precisely located. It is not until the 1st Century AD that Roman commentators describe other tribes residing within this geographical area. At some point before 500 AD, there is no further mention of the Cimbri or Teutones in any source, and the Cimbric Cheronese (Peninsula) is then called Jutland. As we shall see, problems in accomplishing this task are somewhat daunting. For example, there are inconsistencies in datasources, and highly conflicting viewpoints expressed by those interpreting the data. These difficulties can be addressed by a careful sifting of diverse material that has come to light largely due to the storehouse of primary source information accessed by the power of the Internet. Historical, archaeological and genetic data will be integrated to lift the veil that has to date obscured the story of the Cimbri, or Cimbrian, peoples. -

Layout-A K T. MD

Schicksal in Zahlen Informationen zur Arbeit des Volksbundes Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V. Herausgegeben vom: Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge e. V. Werner-Hilpert-Straße 2, 34112 Kassel Internet: www.volksbund.de E-Mail: [email protected] Redaktion und Gestaltung: AWK-Dialog Marketing 6. Auflage - (61) - April 2000 Druck: Graphischer Großbetrieb Pössneck Fotos: Nagel (1), Kammerer (3), Volksbund Archiv Titelbild: Mitarbeiter des Volksbundes suchen in der Steppe von Wolgograd - dem ehemaligen Schlachtfeld von Stalingrad - nach den Gräbern deutscher Soldaten. 2 Aus dem Inhalt Gedenken und Erinnern ..................................... 3 Seit 80 Jahren ein privater Verein ...................... 8-36 Gedenken an Kriegstote ..................................... 8 Sorge für Kriegsgräber ........................................ 11 Ein historisches Ereignis .................................... 37-38 Volkstrauertag ..................................................... 39-44 Totenehrung .......................................................... 40 Aus Gedenkreden ................................................ 41 Zentrales Mahnmal .............................................. 45 Rechtliche Grundlagen ...................................... 48-59 Umbettung von Gefallenen ............................... 60-63 Deutsche Dienststelle ......................................... 64 Gräbernachweis .................................................... 66-72 Grabschmuck ........................................................ 70 Gräbersuche im -

Welsh Kings at Anglo-Saxon Royal Assemblies (928–55) Simon Keynes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Keynes The Henry Loyn Memorial Lecture for 2008 Welsh kings at Anglo-Saxon royal assemblies (928–55) Simon Keynes A volume containing the collected papers of Henry Loyn was published in 1992, five years after his retirement in 1987.1 A memoir of his academic career, written by Nicholas Brooks, was published by the British Academy in 2003.2 When reminded in this way of a contribution to Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman studies sustained over a period of 50 years, and on learning at the same time of Henry’s outstanding service to the academic communities in Cardiff, London, and elsewhere, one can but stand back in awe. I was never taught by Henry, but encountered him at critical moments—first as the external examiner of my PhD thesis, in 1977, and then at conferences or meetings for twenty years thereafter. Henry was renowned not only for the authority and crystal clarity of his published works, but also as the kind of speaker who could always be relied upon to bring a semblance of order and direction to any proceedings—whether introducing a conference, setting out the issues in a way which made one feel that it all mattered, and that we stood together at the cutting edge of intellectual endeavour; or concluding a conference, artfully drawing together the scattered threads and making it appear as if we’d been following a plan, and might even have reached a conclusion. First place at a conference in the 1970s and 1980s was known as the ‘Henry Loyn slot’, and was normally occupied by Henry Loyn himself; but once, at the British Museum, he was for some reason not able to do it, and I was prevailed upon to do it in his place. -

King Aethelbert of Kent

Æthelberht of Kent Æthelberht (also Æthelbert, Aethelberht, Aethelbert, or Ethelbert) (c. 560 – 24 February 616) was King of Kent from about 558 or 560 (the earlier date according to Sprott, the latter according to William of Malmesbury Book 1.9 ) until his death. The eighth-century monk Bede, in his Ecclesiastical History of the English Peo- ple, lists Aethelberht as the third king to hold imperium over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. In the late ninth cen- tury Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Æthelberht is referred to as a bretwalda, or “Britain-ruler”. He was the first English king to convert to Christianity. Æthelberht was the son of Eormenric, succeeding him as king, according to the Chronicle. He married Bertha, the Christian daughter of Charibert, king of the Franks, thus building an alliance with the most powerful state in con- temporary Western Europe; the marriage probably took place before Æthelberht came to the throne. The influ- ence of Bertha may have led to the decision by Pope Gre- gory I to send Augustine as a missionary from Rome. Au- gustine landed on the Isle of Thanet in east Kent in 597. Shortly thereafter, Æthelberht converted to Christianity, churches were established, and wider-scale conversion to Christianity began in the kingdom. Æthelberht provided The state of Anglo-Saxon England at the time Æthelberht came the new mission with land in Canterbury not only for what to the throne of Kent came to be known as Canterbury Cathedral but also for the eventual St Augustine’s Abbey. Æthelberht’s law for Kent, the earliest written code in ginning about 550, however, the British began to lose any Germanic language, instituted a complex system of ground once more, and within twenty-five years it appears fines. -

Bavaria the Bavarians Emerged in a Region North of the Alps, Originally Inhabited by the Celts, Which Had Been Part of the Roman Provinces of Rhaetia and Noricum

Bavaria The Bavarians emerged in a region north of the Alps, originally inhabited by the Celts, which had been part of the Roman provinces of Rhaetia and Noricum. The Bavarians spoke Old High German but, unlike other Germanic groups, did not migrate from elsewhere. Rather, they seem to have coalesced out of other groups left behind by Roman withdrawal late in the 5th century AD. These peoples may have included Marcomanni, Thuringians, Goths, Rugians, Heruli, and some remaining Romans. The name "Bavarian" ("Baiuvari") means "Men of Baia" which may indicate Bohemia, the homeland of the Marcomanni. They first appear in written sources circa 520. Saint Boniface completed the people's conversion to Christianity in the early 8th century. Bavaria was, for the most part, unaffected by the Protestant Reformation, and even today, most of it is strongly Roman Catholic. From about 550 to 788, the house of Agilolfing ruled the duchy of Bavaria, ending with Tassilo III who was deposed by Charlemagne. Three early dukes are named in Frankish sources: Garibald I may have been appointed to the office by the Merovingian kings and married the Lombard princess Walderada when the church forbade her to King Chlothar I in 555. Their daughter, Theodelinde, became Queen of the Lombards in northern Italy and Garibald was forced to flee to her when he fell out with his Frankish over- lords. Garibald's successor, Tassilo I, tried unsuccessfully to hold the eastern frontier against the expansion of Slavs and Avars around 600. Tassilo's son Garibald II seems to have achieved a balance of power between 610 and 616. -

Sicut Scintilla Ignis in Medio Maris: Theological Despair in the Works of Isidore of Seville, Hrotsvit of Gandersheim and Dante Alighieri

SICUT SCINTILLA IGNIS IN MEDIO MARIS: THEOLOGICAL DESPAIR IN THE WORKS OF ISIDORE OF SEVILLE, HROTSVIT OF GANDERSHEIM AND DANTE ALIGHIERI by Kristen Leigh Allen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Kristen Leigh Allen 2009 Abstract Sicut scintilla ignis in medio maris: Theological Despair in the Works of Isidore of Seville, Hrotsvit of Gandersheim and Dante Alighieri. Doctor of Philosophy, 2009. Kristen Leigh Allen, Graduate Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto. When discussing the concept of despair in the Middle Ages, scholars often note how strongly medieval people linked despair with suicide. Indeed, one finds the most recent and comprehensive treatment of the topic in Alexander Murray’s Suicide in the Middle Ages. Murray concludes that most medieval suicides had suffered from “this- worldly” despair, brought on by fatal illness, emotional or material stress, or some other unbearable circumstance. However, Murray also observes that medieval theologians and the people they influenced came to attribute suicide to theological despair, i.e. a failure to hope for God’s mercy. This dissertation investigates the work of three well-known medieval authors who wrote about and very likely experienced such theological despair. In keeping with Murray’s findings, none of these three ultimately committed suicide, thus allowing me to explore how medieval people overcame their theological despair. I have chosen these three authors because they not only wrote about theological despair, but drew from their own experiences when doing so. Their personal testimony was intended to equip their readers with the spiritual tools necessary to overcome their own despair.