The Decline of Computers As a General Purpose Technology: Why Deep Learning and the End of Moore's Law Are Fragmenting Computi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Note 1

EE586 VLSI Design Partha Pande School of EECS Washington State University [email protected] Lecture 1 (Introduction) Why is designing digital ICs different today than it was before? Will it change in future? The First Computer The Babbage Difference Engine (1832) 25,000 parts cost: £17,470 ENIAC - The first electronic computer (1946) The Transistor Revolution First transistor Bell Labs, 1948 The First Integrated Circuits Bipolar logic 1960’s ECL 3-input Gate Motorola 1966 Intel 4004 Micro-Processor 1971 1000 transistors 1 MHz operation Intel Pentium (IV) microprocessor Moore’s Law In 1965, Gordon Moore noted that the number of transistors on a chip doubled every 18 to 24 months. He made a prediction that semiconductor technology will double its effectiveness every 18 months Moore’s Law 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 OF THE NUMBER OF 2 5 4 LOG 3 2 1 COMPONENTS PER INTEGRATED FUNCTION 0 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Electronics, April 19, 1965. Evolution in Complexity Transistor Counts 1 Billion K Transistors 1,000,000 100,000 Pentium® III 10,000 Pentium® II Pentium® Pro 1,000 Pentium® i486 100 i386 80286 10 8086 Source: Intel 1 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Projected Courtesy, Intel Moore’s law in Microprocessors 1000 2X growth in 1.96 years! 100 10 P6 Pentium® proc 1 486 386 0.1 286 Transistors (MT) Transistors 8086 Transistors8085 on Lead Microprocessors double every 2 years 0.01 8080 8008 4004 0.001 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Year Courtesy, Intel Die Size Growth 100 P6 -

Microprocessors History of Computing Nouf Assaid

MICROPROCESSORS HISTORY OF COMPUTING NOUF ASSAID 1 Table of Contents Introduction 2 Brief History 2 Microprocessors 7 Instruction Set Architectures 8 Von Neumann Machine 9 Microprocessor Design 12 Superscalar 13 RISC 16 CISC 20 VLIW 23 Multiprocessor 24 Future Trends in Microprocessor Design 25 2 Introduction If we take a look around us, we would be sure to find a device that uses a microprocessor in some form or the other. Microprocessors have become a part of our daily lives and it would be difficult to imagine life without them today. From digital wrist watches, to pocket calculators, from microwaves, to cars, toys, security systems, navigation, to credit cards, microprocessors are ubiquitous. All this has been made possible by remarkable developments in semiconductor technology enabling in the last 30 years, enabling the implementation of ideas that were previously beyond the average computer architect’s grasp. In this paper, we discuss the various microprocessor technologies, starting with a brief history of computing. This is followed by an in-depth look at processor architecture, design philosophies, current design trends, RISC processors and CISC processors. Finally we discuss trends and directions in microprocessor design. Brief Historical Overview Mechanical Computers A French engineer by the name of Blaise Pascal built the first working mechanical computer. This device was made completely from gears and was operated using hand cranks. This machine was capable of simple addition and subtraction, but a few years later, a German mathematician by the name of Leibniz made a similar machine that could multiply and divide as well. After about 150 years, a mathematician at Cambridge, Charles Babbage made his Difference Engine. -

Analytical Engine, 1838 ALLAN G

Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine, 1838 ALLAN G. BROMLEY Charles Babbage commenced work on the design of the Analytical Engine in 1834 following the collapse of the project to build the Difference Engine. His ideas evolved rapidly, and by 1838 most of the important concepts used in his later designs were established. This paper introduces the design of the Analytical Engine as it stood in early 1838, concentrating on the overall functional organization of the mill (or central processing portion) and the methods generally used for the basic arithmetic operations of multiplication, division, and signed addition. The paper describes the working of the mechanisms that Babbage devised for storing, transferring, and adding numbers and how they were organized together by the “microprogrammed” control system; the paper also introduces the facilities provided for user- level programming. The intention of the paper is to show that an automatic computing machine could be built using mechanical devices, and that Babbage’s designs provide both an effective set of basic mechanisms and a workable organization of a complete machine. Categories and Subject Descriptors: K.2 [History of Computing]- C. Babbage, hardware, software General Terms: Design Additional Key Words and Phrases: Analytical Engine 1. Introduction 1838. During this period Babbage appears to have made no attempt to construct the Analytical Engine, Charles Babbage commenced work on the design of but preferred the unfettered intellectual exploration of the Analytical Engine shortly after the collapse in 1833 the concepts he was evolving. of the lo-year project to build the Difference Engine. After 1849 Babbage ceased designing calculating He was at the time 42 years o1d.l devices. -

Memory Centric Characterization and Analysis of SPEC CPU2017 Suite

Session 11: Performance Analysis and Simulation ICPE ’19, April 7–11, 2019, Mumbai, India Memory Centric Characterization and Analysis of SPEC CPU2017 Suite Sarabjeet Singh Manu Awasthi [email protected] [email protected] Ashoka University Ashoka University ABSTRACT These benchmarks have become the standard for any researcher or In this paper, we provide a comprehensive, memory-centric charac- commercial entity wishing to benchmark their architecture or for terization of the SPEC CPU2017 benchmark suite, using a number of exploring new designs. mechanisms including dynamic binary instrumentation, measure- The latest offering of SPEC CPU suite, SPEC CPU2017, was re- ments on native hardware using hardware performance counters leased in June 2017 [8]. SPEC CPU2017 retains a number of bench- and operating system based tools. marks from previous iterations but has also added many new ones We present a number of results including working set sizes, mem- to reflect the changing nature of applications. Some recent stud- ory capacity consumption and memory bandwidth utilization of ies [21, 24] have already started characterizing the behavior of various workloads. Our experiments reveal that, on the x86_64 ISA, SPEC CPU2017 applications, looking for potential optimizations to SPEC CPU2017 workloads execute a significant number of mem- system architectures. ory related instructions, with approximately 50% of all dynamic In recent years the memory hierarchy, from the caches, all the instructions requiring memory accesses. We also show that there is way to main memory, has become a first class citizen of computer a large variation in the memory footprint and bandwidth utilization system design. -

The Birth, Evolution and Future of Microprocessor

The Birth, Evolution and Future of Microprocessor Swetha Kogatam Computer Science Department San Jose State University San Jose, CA 95192 408-924-1000 [email protected] ABSTRACT timed sequence through the bus system to output devices such as The world's first microprocessor, the 4004, was co-developed by CRT Screens, networks, or printers. In some cases, the terms Busicom, a Japanese manufacturer of calculators, and Intel, a U.S. 'CPU' and 'microprocessor' are used interchangeably to denote the manufacturer of semiconductors. The basic architecture of 4004 same device. was developed in August 1969; a concrete plan for the 4004 The different ways in which microprocessors are categorized are: system was finalized in December 1969; and the first microprocessor was successfully developed in March 1971. a) CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computers) Microprocessors, which became the "technology to open up a new b) RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computers) era," brought two outstanding impacts, "power of intelligence" and "power of computing". First, microprocessors opened up a new a) VLIW(Very Long Instruction Word Computers) "era of programming" through replacing with software, the b) Super scalar processors hardwired logic based on IC's of the former "era of logic". At the same time, microprocessors allowed young engineers access to "power of computing" for the creative development of personal 2. BIRTH OF THE MICROPROCESSOR computers and computer games, which in turn led to growth in the In 1970, Intel introduced the first dynamic RAM, which increased software industry, and paved the way to the development of high- IC memory by a factor of four. -

Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks

9 Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks Kaivalya M. Dixit IBM Corporation “The reputation of current benchmarketing claims regarding system performance is on par with the promises made by politicians during elections.” Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation (SPEC) was founded in October, 1988, by Apollo, Hewlett-Packard,MIPS Computer Systems and SUN Microsystems in cooperation with E. E. Times. SPEC is a nonprofit consortium of 22 major computer vendors whose common goals are “to provide the industry with a realistic yardstick to measure the performance of advanced computer systems” and to educate consumers about the performance of vendors’ products. SPEC creates, maintains, distributes, and endorses a standardized set of application-oriented programs to be used as benchmarks. 489 490 CHAPTER 9 Overview of the SPEC Benchmarks 9.1 Historical Perspective Traditional benchmarks have failed to characterize the system performance of modern computer systems. Some of those benchmarks measure component-level performance, and some of the measurements are routinely published as system performance. Historically, vendors have characterized the performances of their systems in a variety of confusing metrics. In part, the confusion is due to a lack of credible performance information, agreement, and leadership among competing vendors. Many vendors characterize system performance in millions of instructions per second (MIPS) and millions of floating-point operations per second (MFLOPS). All instructions, however, are not equal. Since CISC machine instructions usually accomplish a lot more than those of RISC machines, comparing the instructions of a CISC machine and a RISC machine is similar to comparing Latin and Greek. 9.1.1 Simple CPU Benchmarks Truth in benchmarking is an oxymoron because vendors use benchmarks for marketing purposes. -

Class-Action Lawsuit

Case 3:20-cv-00863-SI Document 1 Filed 05/29/20 Page 1 of 279 Steve D. Larson, OSB No. 863540 Email: [email protected] Jennifer S. Wagner, OSB No. 024470 Email: [email protected] STOLL STOLL BERNE LOKTING & SHLACHTER P.C. 209 SW Oak Street, Suite 500 Portland, Oregon 97204 Telephone: (503) 227-1600 Attorneys for Plaintiffs [Additional Counsel Listed on Signature Page.] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF OREGON PORTLAND DIVISION BLUE PEAK HOSTING, LLC, PAMELA Case No. GREEN, TITI RICAFORT, MARGARITE SIMPSON, and MICHAEL NELSON, on behalf of CLASS ACTION ALLEGATION themselves and all others similarly situated, COMPLAINT Plaintiffs, DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL v. INTEL CORPORATION, a Delaware corporation, Defendant. CLASS ACTION ALLEGATION COMPLAINT Case 3:20-cv-00863-SI Document 1 Filed 05/29/20 Page 2 of 279 Plaintiffs Blue Peak Hosting, LLC, Pamela Green, Titi Ricafort, Margarite Sampson, and Michael Nelson, individually and on behalf of the members of the Class defined below, allege the following against Defendant Intel Corporation (“Intel” or “the Company”), based upon personal knowledge with respect to themselves and on information and belief derived from, among other things, the investigation of counsel and review of public documents as to all other matters. INTRODUCTION 1. Despite Intel’s intentional concealment of specific design choices that it long knew rendered its central processing units (“CPUs” or “processors”) unsecure, it was only in January 2018 that it was first revealed to the public that Intel’s CPUs have significant security vulnerabilities that gave unauthorized program instructions access to protected data. 2. A CPU is the “brain” in every computer and mobile device and processes all of the essential applications, including the handling of confidential information such as passwords and encryption keys. -

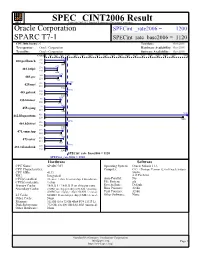

Oracle Corporation: SPARC T7-1

SPEC CINT2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2015 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Oracle Corporation SPECint_rate2006 = 1200 SPARC T7-1 SPECint_rate_base2006 = 1120 CPU2006 license: 6 Test date: Oct-2015 Test sponsor: Oracle Corporation Hardware Availability: Oct-2015 Tested by: Oracle Corporation Software Availability: Oct-2015 Copies 0 300 600 900 1200 1600 2000 2400 2800 3200 3600 4000 4400 4800 5200 5600 6000 6400 6800 7600 1100 400.perlbench 192 224 1040 675 401.bzip2 256 224 666 875 403.gcc 160 224 720 1380 429.mcf 128 224 1160 1190 445.gobmk 256 224 1120 854 456.hmmer 96 224 813 1020 458.sjeng 192 224 988 7550 462.libquantum 416 224 7330 1190 464.h264ref 256 224 1150 956 471.omnetpp 255 224 885 986 473.astar 416 224 862 1180 483.xalancbmk 256 224 1140 SPECint_rate_base2006 = 1120 SPECint_rate2006 = 1200 Hardware Software CPU Name: SPARC M7 Operating System: Oracle Solaris 11.3 CPU Characteristics: Compiler: C/C++/Fortran: Version 12.4 of Oracle Solaris CPU MHz: 4133 Studio, FPU: Integrated 4/15 Patch Set CPU(s) enabled: 32 cores, 1 chip, 32 cores/chip, 8 threads/core Auto Parallel: No CPU(s) orderable: 1 chip File System: zfs Primary Cache: 16 KB I + 16 KB D on chip per core System State: Default Secondary Cache: 2 MB I on chip per chip (256 KB / 4 cores); Base Pointers: 32-bit 4 MB D on chip per chip (256 KB / 2 cores) Peak Pointers: 32-bit L3 Cache: 64 MB I+D on chip per chip (8 MB / 4 cores) Other Software: None Other Cache: None Memory: 512 GB (16 x 32 GB 4Rx4 PC4-2133P-L) Disk Subsystem: 732 GB, 4 x 400 GB SAS SSD -

THE MICROPROCESSOR Z Z the BEGINNING

z THE MICROPROCESSOR z z THE BEGINNING The construction of microprocessors was made possible thanks to LSI (Silicon Gate Technology) developed by the Italian Federico Faggin at Fairchild in 1968. From the 1980s onwards microprocessors are practically the only CPU implementation. z HOW DO MICROPROCESSOR WORK? Most microprocessor work digitally, transforming all the input information into a code of binary number (1 or 0 is called a bit, 8 bit is called byte) z THE FIRST MICROPROCESSOR Intel's first microprocessor, the 4004, was conceived by Ted Hoff and Stanley Mazor. Assisted by Masatoshi Shima, Federico Faggin used his experience in silicon- gate MOS technology (1968 Milestone) to squeeze the 2300 transistors of the 4-bit MPU into a 16-pin package in 1971. z WHAT WAS INTEL 4004 USED FOR? The Intel 4004 was the world's first microprocessor—a complete general-purpose CPU on a single chip. Released in March 1971, and using cutting-edge silicon- gate technology, the 4004 marked the beginning of Intel's rise to global dominance in the processor industry. z THE FIRST PERSONAL COMPUTER WITH MICROPROCESSOR MS-DOSIBM introduces its Personal Computer (PC)The first IBM PC, formally known as the IBM Model 5150, was based on a 4.77 MHz Intel 8088 microprocessor and used Microsoft´s MS-DOS operating system. The IBM PC revolutionized business computing by becoming the first PC to gain widespread adoption by industry. z BIOHACKER z WHO ARE BIOHACKER? Biohackers, also called hackers of life, are people and communities that do biological research in the hacker style: outside the institutions, in an open form, sharing information. -

Poweredge R940 (Intel Xeon Gold 5122, 3.60 Ghz) Specint Rate Base2006 = 1080 CPU2006 License: 55 Test Date: Jun-2017 Test Sponsor: Dell Inc

SPEC CINT2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2017 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Dell Inc. SPECint_rate2006 = 1150 PowerEdge R940 (Intel Xeon Gold 5122, 3.60 GHz) SPECint_rate_base2006 = 1080 CPU2006 license: 55 Test date: Jun-2017 Test sponsor: Dell Inc. Hardware Availability: Jul-2017 Tested by: Dell Inc. Software Availability: Nov-2016 Copies 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000 10000 11000 12000 13000 14000 15000 16000 18000 917 400.perlbench 32 32 762 521 401.bzip2 32 32 487 808 403.gcc 32 32 802 1480 429.mcf 32 624 445.gobmk 32 2010 456.hmmer 32 32 1530 710 458.sjeng 32 32 658 17700 462.libquantum 32 1170 464.h264ref 32 32 1130 554 471.omnetpp 32 32 509 614 473.astar 32 1430 483.xalancbmk 32 SPECint_rate_base2006 = 1080 SPECint_rate2006 = 1150 Hardware Software CPU Name: Intel Xeon Gold 5122 Operating System: SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 12 SP2 CPU Characteristics: Intel Turbo Boost Technology up to 3.70 GHz 4.4.21-69-default CPU MHz: 3600 Compiler: C/C++: Version 17.0.3.191 of Intel C/C++ FPU: Integrated Compiler for Linux CPU(s) enabled: 16 cores, 4 chips, 4 cores/chip, 2 threads/core Auto Parallel: Yes CPU(s) orderable: 2,4 chip File System: xfs Primary Cache: 32 KB I + 32 KB D on chip per core System State: Run level 3 (multi-user) Secondary Cache: 1 MB I+D on chip per core Base Pointers: 32-bit L3 Cache: 16.5 MB I+D on chip per chip Peak Pointers: 32/64-bit Other Cache: None Other Software: Microquill SmartHeap V10.2 Memory: 768 GB (48 x 16 GB 2Rx8 PC4-2666V-R) Disk Subsystem: 1 x 960 GB SATA SSD Other Hardware: None Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation [email protected] Page 1 http://www.spec.org/ SPEC CINT2006 Result spec Copyright 2006-2017 Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation Dell Inc. -

Microprocessors in the 1970'S

Part II 1970's -- The Altair/Apple Era. 3/1 3/2 Part II 1970’s -- The Altair/Apple era Figure 3.1: A graphical history of personal computers in the 1970’s, the MITS Altair and Apple Computer era. Microprocessors in the 1970’s 3/3 Figure 3.2: Andrew S. Grove, Robert N. Noyce and Gordon E. Moore. Figure 3.3: Marcian E. “Ted” Hoff. Photographs are courtesy of Intel Corporation. 3/4 Part II 1970’s -- The Altair/Apple era Figure 3.4: The Intel MCS-4 (Micro Computer System 4) basic system. Figure 3.5: A photomicrograph of the Intel 4004 microprocessor. Photographs are courtesy of Intel Corporation. Chapter 3 Microprocessors in the 1970's The creation of the transistor in 1947 and the development of the integrated circuit in 1958/59, is the technology that formed the basis for the microprocessor. Initially the technology only enabled a restricted number of components on a single chip. However this changed significantly in the following years. The technology evolved from Small Scale Integration (SSI) in the early 1960's to Medium Scale Integration (MSI) with a few hundred components in the mid 1960's. By the late 1960's LSI (Large Scale Integration) chips with thousands of components had occurred. This rapid increase in the number of components in an integrated circuit led to what became known as Moore’s Law. The concept of this law was described by Gordon Moore in an article entitled “Cramming More Components Onto Integrated Circuits” in the April 1965 issue of Electronics magazine [338]. -

Finding a Story for the History of Computing 2018

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Haigh Finding a Story for the History of Computing 2018 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3796 Angenommene Version / accepted version Working Paper Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Haigh, Thomas: Finding a Story for the History of Computing. Siegen: Universität Siegen: SFB 1187 Medien der Kooperation 2018 (Working paper series / SFB 1187 Medien der Kooperation 3). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3796. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:hbz:467-13377 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Finding a Story for the History of Computing Thomas Haigh University of Wisconsin — Milwaukee & University of Siegen WORKING PAPER SERIES | NO. 3 | JULY 2018 Collaborative Research Center 1187 Media of Cooperation Sonderforschungsbereich 1187 Medien der Kooperation Working Paper Series Collaborative Research Center 1187 Media of Cooperation Print-ISSN 2567 – 2509 Online-ISSN 2567 – 2517 URN urn :nbn :de :hbz :467 – 13377 This work is licensed under the Creative Publication of the series is funded by the German Re- Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- search Foundation (DFG). No Derivatives 4.0 International License. The Arpanet Logical Map, February, 1978 on the titl e This Working Paper Series is edited by the Collabora- page is taken from: Bradley Fidler and Morgan Currie, tive Research Center Media of Cooperation and serves “Infrastructure, Representation, and Historiography as a platform to circulate work in progress or preprints in BBN’s Arpanet Maps”, IEEE Annals of the History of in order to encourage the exchange of ideas.