Mike Albaugh Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carol Shaw Regnes Som Den Første Kvinnelige Videospill-Designeren For

Carol Shaw (1955 - ) Carol Shaw regnes som den første kvinnelige videospill-designeren for spillprototypen Polo og spillet 3D Tic-Tac-Toe ved dataselskapet Atari i henholdsvis 1978 og 1979. Hun studerte ved Universitetet i California, og ble uteksaminert i 1970 med en bachelorgrad innen elektroteknikk og en mastergrad i Computer Science, et fagområde som hadde et særdeles lavt antall kvinner på den tiden. Hun var ansatt som microprocessor software engineer ved Atari, Inc., et verdenskjent selskap innen spillindus- trien. I 1978 eide Warner Communications både Atari og Ralph Lauren, og Carol Shaw ble tildelt oppgaven med å designe et spill knyttet til markedsføringen av Ralph Laurens nye parfyme “Polo”. Visstnok ble flere prototyper og håndskrevne instruksjoner sendt til varehuset Bloomingdale’s i New York, men det ble ikke noe av kampanjen, og spillet Polo ble ikke lansert. Polo var en spillproto- type som kunne ha vært det første reklamespillet gjennom tidene. Carol Shaw sies å være den første kvinnelige videospill-designeren for dette spillet, og for 3D Tic-Tac-Toe i 1979 for spillkonsollen Atari 2600. Shaw forlot Atari i 1980 for å arbeide for Tandem Comput- ers. Senere startet hun hos Activision, den første uavhengige spill- programvareutvikler og -distributør. Her designet og utviklet hun spillene Happy Trails og River Raid. Sistnevnte videospill ble lansert av Activision i 1982 for Atari 2600, og er Carol Shaws mest kjente spill. River Raid var en stor suksess og over en million spillkasset- ter ble solgt. Senere overførte selskapet River Raid til en rekke ulike konsoller. Carol Shaw utviklet siden flere andre spill før hun gikk av med pensjon i 1990. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

JAM-BOX Retro PACK 16GB AMSTRAD

JAM-BOX retro PACK 16GB BMX Simulator (UK) (1987).zip BMX Simulator 2 (UK) (19xx).zip Baby Jo Going Home (UK) (1991).zip Bad Dudes Vs Dragon Ninja (UK) (1988).zip Barbarian 1 (UK) (1987).zip Barbarian 2 (UK) (1989).zip Bards Tale (UK) (1988) (Disk 1 of 2).zip Barry McGuigans Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Batman (UK) (1986).zip Batman - The Movie (UK) (1989).zip Beachhead (UK) (1985).zip Bedlam (UK) (1988).zip Beyond the Ice Palace (UK) (1988).zip Blagger (UK) (1985).zip Blasteroids (UK) (1989).zip Bloodwych (UK) (1990).zip Bomb Jack (UK) (1986).zip Bomb Jack 2 (UK) (1987).zip AMSTRAD CPC Bonanza Bros (UK) (1991).zip 180 Darts (UK) (1986).zip Booty (UK) (1986).zip 1942 (UK) (1986).zip Bravestarr (UK) (1987).zip 1943 (UK) (1988).zip Breakthru (UK) (1986).zip 3D Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Bride of Frankenstein (UK) (1987).zip 3D Grand Prix (UK) (1985).zip Bruce Lee (UK) (1984).zip 3D Star Fighter (UK) (1987).zip Bubble Bobble (UK) (1987).zip 3D Stunt Rider (UK) (1985).zip Buffalo Bills Wild West Show (UK) (1989).zip Ace (UK) (1987).zip Buggy Boy (UK) (1987).zip Ace 2 (UK) (1987).zip Cabal (UK) (1989).zip Ace of Aces (UK) (1985).zip Carlos Sainz (S) (1990).zip Advanced OCP Art Studio V2.4 (UK) (1986).zip Cauldron (UK) (1985).zip Advanced Pinball Simulator (UK) (1988).zip Cauldron 2 (S) (1986).zip Advanced Tactical Fighter (UK) (1986).zip Championship Sprint (UK) (1986).zip After the War (S) (1989).zip Chase HQ (UK) (1989).zip Afterburner (UK) (1988).zip Chessmaster 2000 (UK) (1990).zip Airwolf (UK) (1985).zip Chevy Chase (UK) (1991).zip Airwolf 2 (UK) -

Governor's Blue Ribbon Task Force on Parks and Outdoor Recreation

GOVERNOR’S BLUE RIBBON PARKS & OUTDOOR RECREATION TASK FORCE | FINAL RECOMMENDATIONS TO GOVERNOR INSLEE September 19, 2014 “We want our children to experience, enjoy, learn about, and become lifetime stewards of Washington’s magnificent natural resources.” - Governor Jay Inslee Acknowledgements On behalf of the Blue Ribbon Task Force on Parks and Outdoor Recreation, the Washington State Recreation and Conservation Office is pleased to submit this final report to Governor Inslee. It represents thoughtful engagement throughout the six-month process and over 3,700 comments gathered from stakeholders and citizens from across the State. The 29 members were supported by the Recreation and Conservation Office and their consultant partners. We wish to thank Governor Inslee, task force members, stakeholders, and the public for their time and commitment to this process. The collective insight and perspective is captured in this report. Task Force Voting Members Barb Chamberlain Task Force co-chair and Executive Director, Washington Bikes Doug Walker Task Force co-chair and Chair, The Wilderness Society Marc Berejka Director Government and Community Affairs, REI Joshua Brandon Military Organizer, Sierra Club Outdoors Russ Cahill Retired WA and CA State Parks Manager Dale Denney Owner, Bearpaw Outfitters Patty Graf-Hoke CEO, Visit Kitsap Peninsula George Harris Executive Director, Northwest Marine Trade Association Connor Inslee COO and Program Director, Outdoors for All John Keates Director, Mason County Facilities, Parks and Trails Department Ben -

Premiere Issue Monkeying Around Game Reviews: Special Report

Atari Coleco Intellivision Computers Vectrex Arcade ClassicClassic GamerGamer Premiere Issue MagazineMagazine Fall 1999 www.classicgamer.com U.S. “Because Newer Isn’t Necessarily Better!” Special Report: Classic Videogames at E3 Monkeying Around Revisiting Donkey Kong Game Reviews: Atari, Intellivision, etc... Lost Arcade Classic: Warp Warp Deep Thaw Chris Lion Rediscovers His Atari Plus! · Latest News · Guide to Halloween Games · Win the book, “Phoenix” “As long as you enjoy the system you own and the software made for it, there’s no reason to mothball your equipment just because its manufacturer’s stock dropped.” - Arnie Katz, Editor of Electronic Games Magazine, 1984 Classic Gamer Magazine Fall 1999 3 Volume 1, Version 1.2 Fall 1999 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Chris Cavanaugh - [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sarah Thomas - [email protected] STAFF WRITERS Kyle Snyder- [email protected] Reset! 5 Chris Lion - [email protected] Patrick Wong - [email protected] Raves ‘N Rants — Letters from our readers 6 Darryl Guenther - [email protected] Mike Genova - [email protected] Classic Gamer Newswire — All the latest news 8 Damien Quicksilver [email protected] Frank Traut - [email protected] Lee Seitz - [email protected] Book Bytes - Joystick Nation 12 LAYOUT/DESIGN Classic Advertisement — Arcadia Supercharger 14 Chris Cavanaugh PHOTO CREDITS Atari 5200 15 Sarah Thomas - Staff Photographer Pong Machine scan (page 3) courtesy The “New” Classic Gamer — Opinion Column 16 Sean Kelly - Digital Press CD-ROM BIRA BIRA Photos courtesy Robert Batina Lost Arcade Classics — ”Warp Warp” 17 CONTACT INFORMATION Classic Gamer Magazine Focus on Intellivision Cartridge Reviews 18 7770 Regents Road #113-293 San Diego, Ca 92122 Doin’ The Donkey Kong — A closer look at our 20 e-mail: [email protected] on the web: favorite monkey http://www.classicgamer.com Atari 2600 Cartridge Reviews 23 SPECIAL THANKS To Sarah. -

Imitation-Driven Cultural Collapse

1 Imitation-driven Cultural Collapse a,* a,* 2 Salva Duran-Nebreda and Sergi Valverde a 3 Evolution of Technology Lab, Institute of Evolutionary Biology (UPF-CSIC), Passeig de la Barceloneta, E-08003, 4 Barcelona. * 5 [email protected]; [email protected] 6 ABSTRACT A unique feature of human society is its ever-increasing diversity and complexity. Although individuals can generate meaningful variation, they can never create the whole cultural and technological knowledge sustaining a society on their own. Instead, social transmission of innovations accounts for most of the accumulated human knowledge. The natural cycle of cumulative culture entails fluctuations in the diversity of artifacts and behaviours, with sudden declines unfolding in particular domains. Cultural collapses have been attributed to exogenous causes. Here, we define a theoretical framework to explain endogenous cultural collapses, driven by an exploration-reinforcement imbalance. This is demonstrated by the historical market crash of the 7 Atari Video Console System in 1983, the cryptocurrency crash of 2018 and the production of memes in online communities. We identify universal features of endogenous cultural collapses operating at different scales, including changes in the distribution of component usage, higher compressibility of the cultural history, marked decreases in complexity and the boom-and-bust dynamics of diversity. The loss of information is robust and independent of specific system details. Our framework suggests how future endogenous collapses can be mitigated by stronger self-policing, reduced costs to innovation and increased transparency of cost-benefit trade-offs. 8 Introduction 9 Comparative studies between humans and other animals emphasize the unique aspects of human learning, including their 1,2 10 capacity for high-fidelity copying . -

Owner's Manual Model Cx-2600

OWNER'S MANUAL MODEL CX-2600 1 Contents Getting Started ……………………….. 3 Main Menu Explanation ……………………….. 5 Game Listing ……………………….. 6 Credits ……………………….. 106 Technical Support ……………………….. 107 Terms And Conditions ……………………….. 108 2 Getting Started Health Warnings and Precautions • Video games may cause a small percentage of individuals to experience seizures or have momentary loss of consciousness when viewing certain kinds of flashing lights or patterns on a television screen. Certain conditions may include epileptic symptoms even in persons with no prior history or seizures or epilepsy. • If you or anyone in your family has an epileptic condition, consult your physician prior to game play. • It is recommended that parents observe their children when their children play video games. • If you or your child experiences any of the following symptoms: dizziness, altered vision, eye or muscle twitching, involuntary movements, loss of awareness, disorientation, or convulsions, discontinue use immediately. • Some people may experience fatigue or discomfort after playing for a long time. If your hands or arms become tired or uncomfortable during game play, stop playing immediately. • If you continue to experience soreness or discomfort during or after play, stop playing and consult your physician. • If your hands, wrists or arms have been injured or strained in other activities, use of your system could aggravate the condition. As necessary consult your physician before playing video games. • Do not sit or stand too close to the television. • Do not play if you are tired or need sleep. • Always play in a well-lit room. • Be sure to take a 10- to 15- minute break, at least every hour, while playing. -

Website Listing Ajax

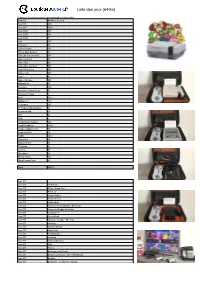

Liste des jeux (64Go) Cliquez sur le nom des consoles pour descendre au bon endroit Console Nombre de jeux Atari ST 274 Atari 800 5627 Atari 2600 457 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 51 C64 150 Channel F 34 Coleco Vision 151 Family Disk System 43 FBA Libretro (arcade) 647 Game & watch 58 Game Boy 621 Game Boy Advance 951 Game Boy Color 501 Game gear 277 Lynx 84 Mame (arcade) 808 Nintento 64 78 Neo-Geo 152 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 NES 1812 Odyssey 2 125 Pc Engine 291 Pc Engine Supergraphx 97 Pokémon Mini 26 PS1 54 PSP 2 Sega Master System 288 Sega Megadrive 1030 Sega megadrive 32x 30 Sega sg-1000 59 SNES 1461 Stellaview 66 Sufami Turbo 15 Thomson 82 Vectrex 75 Virtualboy 24 Wonderswan 102 WonderswanColor 83 Total 16877 Atari ST Atari ST 10th Frame Atari ST 500cc Grand Prix Atari ST 5th Gear Atari ST Action Fighter Atari ST Action Service Atari ST Addictaball Atari ST Advanced Fruit Machine Simulator Atari ST Advanced Rugby Simulator Atari ST Afterburner Atari ST Alien World Atari ST Alternate Reality - The City Atari ST Anarchy Atari ST Another World Atari ST Apprentice Atari ST Archipelagos Atari ST Arcticfox Atari ST Artificial Dreams Atari ST Atax Atari ST Atomix Atari ST Backgammon Royale Atari ST Balance of Power - The 1990 Edition Atari ST Ballistix Atari ST Barbarian : Le Guerrier Absolu Atari ST Battle Chess Atari ST Battle Probe Atari ST Battlehawks 1942 Atari ST Beach Volley Atari ST Beastlord Atari ST Beyond the Ice Palace Atari ST Black Tiger Atari ST Blasteroids Atari ST Blazing Thunder Atari ST Blood Money Atari ST BMX Simulator Atari ST Bob Winner Atari ST Bomb Jack Atari ST Bumpy Atari ST Burger Man Atari ST Captain Fizz Meets the Blaster-Trons Atari ST Carrier Command Atari ST Cartoon Capers Atari ST Catch 23 Atari ST Championship Baseball Atari ST Championship Cricket Atari ST Championship Wrestling Atari ST Chase H.Q. -

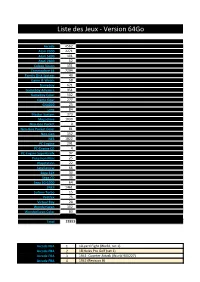

Liste Des Jeux - Version 64Go

Liste des Jeux - Version 64Go Arcade 4562 Atari 2600 2271 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 52 Coleco Vision 151 Commodore 64 7294 Family Disk System 43 Game & Watch 58 Gameboy 621 Gameboy Advance 951 Gameboy Color 502 Game Gear 277 GX4000 25 Lynx 84 Master System 373 Megadrive 1030 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo 152 NES 1822 PC-Engine 291 PC-Engine CD 4 PC-Engine SuperGrafx 97 Pokemon Mini 25 Playstation 22 Satellaview 66 Sega 32X 30 Sega CD 35 Sega SG-1000 64 SNES 1461 Sufami Turbo 15 Vectrex 75 Virtual Boy 24 WonderSwan 102 WonderSwan Color 83 Total 22853 Arcade FBA 1 10-yard Fight (World, set 1) Arcade FBA 2 18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) Arcade FBA 3 1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) Arcade FBA 4 1942 (Revision B) Arcade FBA 5 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) Arcade FBA 6 1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) Arcade FBA 7 1943: The Battle of Midway Mark II (US) Arcade FBA 8 1943mii Arcade FBA 9 1944 : The Loop Master (USA 000620) Arcade FBA 10 1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) Arcade FBA 11 1945k III Arcade FBA 12 1945k III (newer, OPCX2 PCB) Arcade FBA 13 19XX : The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Arcade FBA 14 19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) Arcade FBA 15 2020 Super Baseball Arcade FBA 16 2020 Super Baseball (set 1) Arcade FBA 17 3 Count Bout Arcade FBA 18 3 Count Bout / Fire Suplex (NGM-043)(NGH-043) Arcade FBA 19 3x3 Puzzle (Enterprise) Arcade FBA 20 4 En Raya (set 1) Arcade FBA 21 4 Fun In 1 Arcade FBA 22 4-D Warriors (315-5162) Arcade FBA 23 4play Arcade FBA 24 64th. -

Jigsaw Puzzles Italltogetherputting Exhibit Opening:Jigsaw Puzzles: Saturday, June23 Timed-Ticket Only

Spring 2018 • Volume 8 • Issue 3 News and Events for Members, Donors, and Friends P L AY Time Exhibit Now Open! Page 2 Rockets, Robots, Princess Neverland Neighborhood Calendar 4 and Ray Guns 5 Palooza 7 Weekend 8 of Play 15 of Events NEW EXHIBIT NEW EXHIBIT Exhibit Now Open! Let your imagination soar! Be an builder by attaching blue or purple Bust a move in the dance studio astronaut, rescue pilot, construction siding to the frame of a house. Or be and practice your footwork while worker, actor, and more in The part of the remodel and demolition listening to classic, country, and Strong’s newest permanent exhibit— team by knocking the existing siding contemporary music. Imagination Destination. Role-play out! After, use an air-powered I’d like to be in inspiring spaces bursting with cannon to shoot shingles to the top Discover an engineer. physical challenges, such as a rescue of the house, climb the ladder, and Step through a giant magnifying I want to helicopter, construction site, rocket complete the roof. Drop used shingles glass and shrink down to the size ship, and theater. down a giant trash shoot into the of a bug in an area specially build houses! I want to waiting dumpster below. designed for toddlers. Crawl through be a doctor. Command a honeycomb maze and meet giant, Assume the captain’s chair and take Then travel down into the sewers to plush bumblebees. Wind through a command of the bridge of the U.S.S. inspect city pipes and use engineering front yard brimming with huge blades Strong—a futuristic spaceship replete skills to repair missing pieces. -

Retro Game Programming Copyright © 2011 by Brainycode.Com

Retro Game Programming Copyright © 2011 by brainycode.com Retro Game Programming How this book got started? ................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 5 What is a retro game? ..................................................................................................... 6 What are we trying to do? ............................................................................................... 7 What do you need?.......................................................................................................... 8 What should you know?.................................................................................................. 9 What‘s the plan? ............................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1: The Early History of Video Games ................................................................. 11 Just Having Fun ............................................................................................................ 12 A germ of an idea ...................................................................................................... 12 The First Pong Game ................................................................................................ 12 Spacewar! ................................................................................................................. -

Entombed: an Archaeological Examination of an Atari 2600 Game

Entombed An archaeological examination of an Atari 2600 game John Aycocka and Tara Copplestoneb a Department of Computer Science, University of Calgary, 2500 University Drive NW, Calgary, Alberta, Canada b Centre for Digital Heritage, University of York, Department of Archaeology, Heslington, UK Abstract The act and experience of programming is, at its heart, a fundamentally human activity that results in the production of artifacts. When considering programming, therefore, it would be a glaring omission to not involve people who specialize in studying artifacts and the human activity that yields them: archaeologists. Here we consider this with respect to computer games. We draw from the nascent archaeological subarea of archaeogaming to carry out a digital excavation of the code and techniques used in the implementation of Entombed, an Atari 2600 game released in 1982 by US Games. The player in this game is, appropriately, an archaeologist who must make their way through a zombie-infested maze. Maze generation is a fruitful area for comparative retrogame archaeology, because a number of early games on different platforms featured mazes, and their variety of approaches can be compared. The maze in Entombed is particularly interesting: it is shaped in part by the extensive real-time constraints of the Atari 2600 platform, and also had to be generated efficiently and use next to no memory. We reverse engineered key areas of the game’s codeto uncover its unusual maze-generation algorithm, which we have also built a reconstruction of, and analyzed the mysterious table that drives it. In addition, we discovered what appears to be a 35-year-old bug in the code, as well as direct evidence of code-reuse practices amongst game developers.