Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Republic of Azerbaijan-Early Parliamentary Elections, 9 February 2020

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Republic of Azerbaijan-Early Parliamentary Elections, 9 February 2020 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The restrictive legislation and political environment prevented genuine competition in the 9 February 2020 early parliamentary elections in Azerbaijan, despite a high number of candidates. Some prospective candidates were denied the right to stand, but candidate registration process was otherwise inclusive. Voters were not provided with a meaningful choice due to a lack of real political discussion. Many candidates used social media to reach out to the voters, but this did not compensate the absence of campaign coverage in traditional media. Instances of pressure on voters, candidates and their representatives were observed. The election administration was well resourced and met legal deadlines, and the Central Election Commission made concerted efforts to act transparently and was welcoming towards international observers. However, significant procedural violations during counting and the tabulation raised concerns whether the results were established honestly. On 5 December following an appeal of the parliament, and with the consent of the Constitutional Court, the president announced early parliamentary elections to be held on 9 February 2020, nine months before the regular term for elections. In its appeal to the president, parliament justified the call for early elections by the need to harmonize legislative work with the pace of economic, judicial and social reforms set by the president. Parliamentary elections are primarily regulated by the Constitution and the Election Code. Constitution provides for freedoms of expression, assembly, association, movement, access to information, and the right to take part in political life, but the primary legislation significantly restricts these freedoms. -

Kebijakan Luar Negeri Qatar Dalam Memberikan Dukungan Terhadap National Transitional Council (Ntc) Terkait Krisis Politik Di Libya (2011-2012)

KEBIJAKAN LUAR NEGERI QATAR DALAM MEMBERIKAN DUKUNGAN TERHADAP NATIONAL TRANSITIONAL COUNCIL (NTC) TERKAIT KRISIS POLITIK DI LIBYA (2011-2012) Skripsi Diajukan Untuk Memenuhi Persyaratan Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Sosial (S.Sos) Oleh: Rahmi Kamilah 1110113000050 PROGRAM STUDI HUBUNGAN INTERNASIONAL FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA JAKARTA 2014 PERNYATAAN BEBAS PLAGIARISME Skripsi yang berjudul: KEBIJAKAN LUAR NEGERI QATAR DALAM MEMBERIKAN DUKUNGAN TERHADAP PIHAK NATIONAL TRANSITIONAL COUNCIL (NTC) TERKAIT KRISIS POLITIK DI LIBYA (2011-2012) 1. Merupakan hasil karya saya yang diajukan untuk memenuhi salah satu persyaratan memperoleh gelar Strata 1 di Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 2. Semua sumber yang saya gunakan dalam penulisan ini telah saya cantumkan sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku di Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 3. Jika di kemudian hari terbukti bahwa karya saya ini bukan hasil karya asli saya atau merupakan hasil jiplakan dari karya orang lain, maka saya bersedia menerima sanksi yang berlaku di Universitas Islam Negeri (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. Jakarta, 23 Oktober 2014 Rahmi Kamilah ii iii iv ABSTRAKSI Skripsi ini menganalisa tentang kebijakan luar negeri Qatar terkait krisis politik di Libya pada periode 2011-2012. Skripsi ini bertujuan untuk melihat faktor apa saja yang mendorong Qatar untuk memberikan dukungan kepada pihak oposisi dalam krisis politik di Libya. Sumber data yang diperoleh untuk melengkapi penulisan skripsi ini ialah melalui pengumpulan studi kepustakaan. Dalam skripsi ini ditemukan bahwa fenomena Arab Spring yang terjadi di Timur Tengah berdampak luas terhadap perpolitikan kawasan tersebut. Salah satu faktor utama yang mendorong gerakan revolusi ialah permasalahan ekonomi. Qatar, sebagai negara dengan pertumbuhan ekonomi yang tinggi menjadi salah satu negara kawasan yang tidak mengalami revolusi tersebut. -

Esi Document Id 128.Pdf

Generation Facebook in Baku Adnan, Emin and the Future of Dissent in Azerbaijan Berlin – Istanbul 15 March 2011 “... they know from their own experience in 1968, and from the Polish experience in 1980-1981, how suddenly a society that seems atomized, apathetic and broken can be transformed into an articulate, united civil society. How private opinion can become public opinion. How a nation can stand on its feet again. And for this they are working and waiting, under the ice.” Timothy Garton Ash about Charter 77 in communist Czechoslovakia, February 1984 “How come our nation has been able to transcend the dilemma so typical of defeated societies, the hopeless choice between servility and despair?” Adam Michnik, Letter from the Gdansk Prison, July 1985 Table of contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... I Cast of Characters .......................................................................................................................... II 1. BIRTHDAY FLOWERS ........................................................................................................ 1 2. A NEW GENERATION ......................................................................................................... 4 A. Birth of a nation .............................................................................................................. 4 B. How (not) to make a revolution ..................................................................................... -

Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan1

Declassified AS/Jur (2019) 01 22 January 2019 ajdoc01 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Political prisoners in Azerbaijan1 Introductory Memorandum Rapporteur: Ms Thorhildur Sunna ÆVARSDÓTTIR, Iceland, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group 1 Introduction 1.1. Procedure 1. On 1 June 2018, the motion for a resolution on “Political prisoners in Azerbaijan” (Doc. 14538) was referred to the Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights for report.2 I was appointed rapporteur by the Committee at its meeting in Strasbourg on 26 June 2018. 1.2. Issues at stake 2. The issue of political prisoners in Azerbaijan has been of concern to the Council of Europe since the time of the country’s accession. Following the 2001 examination of cases by the independent experts of the Secretary General (SG/Inf(2001)34, discussed below), the Parliamentary Assembly, in its Resolution 1272 (2002) on political prisoners in Azerbaijan, reiterated that no-one may be imprisoned for political reasons in a Council of Europe member state. In its Resolution 1359 (2004), the Assembly “formally ask[ed] the government of Azerbaijan for the immediate release on humanitarian grounds of political prisoners whose state of health is very critical, prisoners whose trials were illegal, prisoners having been political activists or eminent members of past governments, and members of their families, friends or persons who were linked to them … [and] the remaining political prisoners already identified on the experts' list.” In 2005, the Assembly adopted Resolution 1457 and Recommendation 1711, recalling its previous resolutions and, inter alia, calling on the Committee of Ministers to join it in adopting a joint position on the issue of political prisoners in Azerbaijan. -

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe for Suggestions and Comments

Unofficial translation* SUMMARY REPORT UNDER THE PROTOCOL ON WATER AND HEALTH THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN Part One General aspects 1. Were targets and target dates established in your country in accordance with article 6 of the Protocol? Please provide detailed information on the target areas in Part Three. YES ☐ NO ☐ IN PROGRESS If targets have been revised, please provide details here. 2. Were they published and, if so, how? Please explain whether the targets and target dates were published, made available to the public (e.g. online, official publication, media) and communicated to the secretariat. The draft document on target setting was presented in December 2015 to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and United Nations Economic Commission for Europe for suggestions and comments. After the draft document review, its discussion with the public is planned. To get suggestions and comments it will be made available on the website of Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Azerbaijan Republic and Ministry of Health of Azerbaijan Republic. Azerbaijan Republic ratified the Protocol on Water and Health in 2012 and as a Protocol Party participated in two cycles of the previous reporting. At present the targets project is prepared and sent to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. It should be noted that the seminar to support the progress of setting targets under the Protocol on Water and Health was held in Baku on 29 September 2015. More than 40 representatives of different ministries and agencies, responsible for water and health issues, participated in it. -

Govts Seek Facebook Info

SUBSCRIPTION WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 28, 2013 SHAWWAL 21, 1434 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Brotherhood US heat wave Wildfire rages on, Arsenal in CL leader denies prompts early threatens San for 16th ‘terror’ 7claims school10 dismissals Francisco10 water straight20 year Max 45º ‘Ready to hit’ Min 31º High Tide 03:48 & 17:31 West powers could attack Syria ‘in days’ Low Tide 11:01 & 22:52 40 PAGES NO: 15911 150 FILS AMMAN: Western powers could attack Syria within days, envoys from the United States and its allies have told rebels fighting President Bashar Al-Assad, sources who attended the meeting said yesterday. US forces in the region are “ready to go”, Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said, as Washington and its European and Middle Eastern partners honed plans to punish Assad for a major poison gas attack last week that killed hundreds of civilians. Several sources who attended a meeting in Istanbul on Monday between Syrian opposition leaders and diplomats from Washington and other governments said that the rebels were told to expect military action and to get ready to negotiate a peace. “The opposition was told in clear terms that action to deter further use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime could come as early as in the next few days, and that they should still prepare for peace talks at Geneva,” one of the sources said. Ahmad Jarba, president of the Syrian National Coalition, met envoys from 11 states in the Friends of Syria group, including Robert Ford, the US ambassador to Syria, at an Istanbul hotel. United Nations chemical weapons investigators, who finally crossed the frontline to take samples on Monday, put off a second trip to rebel-held suburbs of Damascus. -

A Descriptive Study of Social and Economic Conditions

55 LIFE IN NAKHICHEVAN AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC: A descriptive study of social and economic conditions Supported by UNDP/ILO Ayse Kudat Senem Kudat Baris Sivri Social Assessment, LLC July 15, 2002 55 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary and Next Steps Preface Characteristics of the Region History Governance Demographics Household Demographics and Employment Conditions Employment/ Unemployment Education Economic Assessment Government Expenditures NAR’s Economic Statistics Household Expenditure Structure Income Structure Housing Conditions Determinants of Welfare Agriculture Sector in NAR Water Electricity Financing Feed for Livestock Magnitude of Land Holding Subsidies Markets NAR Region District By District Infrastructure Sector Energy Power Generation Natural Gas Project Water Supply Transportation Social Infrastructure 56 57 Health Education Enterprise Sector People’s Priorities Issues Relating to Income Generation Trust and Vision Money and Banking Community Development ARRA Damage Assessment for the Region Other Donor Activities 57 58 Summary and Next Steps The 354,000 people who live in the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic (NAR) present a unique development challenge for the Government of Azerbaijan and for the international community. Cut off and blockaded from the rest of Azerbaijan as a result of the conflict with Armenia, their traditional economic structure and markets destroyed by the collapse of the former Soviet Union, their physical and social infrastructure hampered by a decade or more of lack of maintenance and rehabilitation funding, NAR’s present status is worse than much of the rest of the country and its prospects for the future require imagination and innovative thinking. This report deals with the challenges of NAR today and what peoples’ priorities are for the future. -

General Assembly Security Council Seventy-Fifth Session Seventy-Fifth Year Agenda Items 34, 71 and 135

United Nations A/75/356–S/2020/947 General Assembly Distr.: General 28 September 2020 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Seventy-fifth session Seventy-fifth year Agenda items 34, 71 and 135 Prevention of armed conflict Right of peoples to self-determination The responsibility to protect and the prevention of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity Letter dated 27 September 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General I have the honour to enclose herewith a letter from Zohrab Mnatsakanyan, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia, regarding the large-scale military offensive launched by the Azerbaijani armed forces against Nagorno - Karabakh on 27 September 2020 (see annex). I kindly request that the present letter and its annex be circulated as a document of the General Assembly, under agenda items 34, 71 and 135, and of the Security Council. (Signed) Mher Margaryan Ambassador Permanent Representative 20-12655 (E) 011020 *2012655* A/75/356 S/2020/947 Annex to the letter dated 27 September 2020 from the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Excellency, On 27 September, Azerbaijani armed forces launched large-scale airborne, missile, and land attack along the entire line of contact between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan, targeting civilian settlements, infrastructure, and schools, including in the capital city of Stepanakert. There were also casualties among civilians: a woman and a child were killed during the very first strikes. The aggression was well-prepared and any reference by the Azerbaijani side to an alleged “counterattack” is utterly deceptive. -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2

No. 114 March 2020 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html FORMAL AND INFORMAL POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS Special Editors: Farid Guliyev and Lusine Badalyan (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus 2 ■■Post-Velvet Transformations in Armenia: Fighting an Oligarchic Regime 3 By Nona Shahnazarian (Institute for Archaeology and Ethnography at the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan) ■■Formal-Informal Relations in Azerbaijan 7 By Farid Guliyev (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■From a Presidential to a Parliamentary Government in Georgia 11 By Levan Kakhishvili (Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences, Germany) Research Centre Center Center for Eastern European German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies CRRC-Georgia East European Studies Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University of Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2 Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus Over the past decade, the three republics of the South Caucasus made changes to their constitutions. Georgia shifted from presidentialism to a dual executive system in 2012 and then, in 2017, amended its constitution to transform into a European-style parliamentary democracy. In Armenia, faced with the presidential term limit, the former President Sargsyan initiated constitutional reforms in 2013, which in 2015 resulted in Armenia’s moving from a semipresidential system to a parliamentary system. While this allowed the incumbent party to gain the majority of seats in the April 2017 parliamentary election and enabled Sargsyan to continue as a prime minister, the shift eventually backfired, spilling into a mass protest, the ousting of Sargsyan from office, and the victory of Nikol Pashinyan’s bloc in a snap parliamentary election in December 2018. -

Economic and Social Council

UNITED NATIONS E Economic and Social Distr. Council GENERAL E/CN.4/2004/62/Add.1 26 March 2004 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH ONLY COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Sixtieth session Agenda item 11 (c) CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS, INCLUDING QUESTIONS OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION The right to freedom of opinion and expression Addendum ∗ Summary of cases transmitted to Governments and replies received ∗ ∗ The present document is being circulated in the language of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions GE.04-12400 E/CN.4/2004/62/Add.1 Page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Introduction 1 – 2 5 SUMMARY OF CASES TRANSMITTED AND REPLIES RECEIVED 3 – 387 5 Afghanistan 3 – 5 5 Albania 6 – 7 6 Algeria 8 – 25 6 Argentina 26 – 34 11 Armenia 35 – 38 13 Azerbaijan 39 – 66 15 Bangladesh 67 – 87 30 Belarus 88 – 94 36 Benin 95 – 96 39 Bolivia 97 – 102 39 Botswana 103 – 106 42 Brazil 107 -108 43 Burkina Faso 109 -111 43 Cambodia 112 – 115 44 Cameroon 116 – 127 45 Central African Republic 128 – 132 49 Chad 133 – 135 50 Chile 136 – 138 51 China 139 – 197 52 Colombia 198 – 212 71 Comoros 213 – 214 75 Côte d’Ivoire 215 – 219 75 Cuba 220 – 237 77 Democratic Republic of the Congo 238 – 257 82 Djibouti 258 – 260 90 Dominican Republic 261 – 262 91 Ecuador 263 – 266 91 Egypt 267 – 296 92 El Salvador 297 – 298 100 Eritrea 299 – 315 100 Ethiopia 316 – 321 104 Gabon 322 – 325 106 Gambia 326 – 328 108 Georgia 329 – 332 109 Greece 333 – 334 111 Guatemala 335 – 347 111 Guinea-Bissau 348 – 351 116 E/CN.4/2004/62/Add.1 -

Great Spotted Cuckoo Clamator Glandarius, a New Species for Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukr ainian Journal of Ecology, 2021, 11(3), 75-78, doi: 10.15421/2021_146 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Great spotted cuckoo Clamator glandarius, a new species for Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic A.F. Mammadov1*, A.V. Matsyura2, E.H. Sultanov3, A. Bayramov4 1 Institute of Bioresources of the Nakhchivan Branch of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, 10 Babek St., Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan Republic 2 Altai State University, 61 Lenin St., Barnaul, Russian Federation 3 Azerbaijan Ornithological Society, Baku Engineering University, Baku, Azerbaijan 4 Institute of Bioresources of the Nakhchivan Branch of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, 10 Babek St., Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan Republic *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 10.04.2021. Accepted 22.05.2021 Clamator glandarius is reported from the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. During the first field trip, one individual was observed, and two individuals during the second trip for species mating were registered. Keywords: Great spotted cuckoo, Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, mating, breeding season Introduction The Caucasus is one of the biodiversity hotspots, including Georgia, Azerbaijan (Nakhchivan AR), Armenia, and partly northern Iran (Fig. 1). According to Conservation International and WWF, this region is home to many endemic species and is one of the essential hotspot regions in terms of biodiversity (https://www.caucasus-naturefund.org/ecoregion/). The formation of the Caucasus goes back to the Oligocene age (33.7–23.8 Ma); while it was a small continental island in this period, it became a natural barrier by rising at the end of the Pliocene (5–2 Ma) (Demirsoy, 2008). -

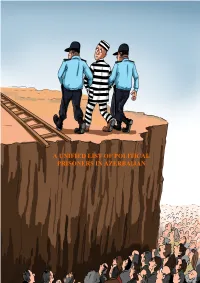

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested