CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

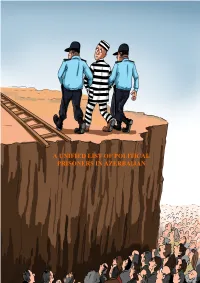

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Eap CSF Roadmap Report Overview 13 Nov 2013

THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP ROADMAP TO THE VILNIUS SUMMIT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ROADMAP IMPLEMENTATION BY THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM This project is funded by the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP ROADMAP TO THE VILNIUS SUMMIT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ROADMAP IMPLEMENTATION BY THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM MAY 2012 – OCTOBER 2013 An Open Road from Vilnius to Riga by Jeff Lovitt, Executive Director, PASOS ...................................................................................... 3 ARMENIA: Association Agreement stopped in its tracks by Boris Navasardian, Yerevan Press Club President, Arevhat Grigoryan, Yerevan Press Club Expert, Mikayel Hovhannisyan, Europe Program Manager with Eurasia Partnership Foundation, Heriknaz Harutyunyan, Yerevan Press Club Expert ....................................................................... 7 AZERBAIJAN: Participatory policymaking should be priority by Gubad Ibadoglu, Public Initiative Center, Araz Aslanli and Nazim Jafarov, Caucasus Strategic Analytical Center ...................................... 21 BELARUS: Dialogue limited to technical and diplomatic level by Andrei Yahorau, Center for European Transformation ............................................................ 35 GEORGIA: Civil society gains greater say in policymaking by Tamara Pataraia, Manana Kochladze, Tamar Khidasheli, Kakha Gogolashvili ...................... -

12 Azerbaijan: Going It Alone

12 Azerbaijan: Going It Alone Svante E. Cornell Over the past two decades, Azerbaijan has been among the countries most reti- cent to engage in integration projects among post-Soviet states. In fact, from the early 1990s onward, Azerbaijan resisted Russian efforts to integrate the country into various institutions. Since then, it has taken a position that can be generally described as being somewhat more accommodating than Georgia’s position toward Moscow, and somewhat more forward than those of Uzbeki- stan and Turkmenistan. In that context, it should come as no surprise that Azerbaijan has rejected offers to join the Customs Union or upcoming Eurasian Union, but it also has maintained a low profile on the matter. Economic Prospects Analysts have pointed to benefits as well as drawbacks that membership in the Customs Union and Eurasian Union would bring to Azerbaijan. These analyses are practically unanimous in noting that the negatives outweigh the positives. Even semi-official Russian analysts have acknowledged this, with one noting that “if Azerbaijan joins the Customs Union, that it is jointly with Turkey and this will not happen soon because of the nature of the Azerbaijani economy.”1 The benefits of Azerbaijan joining the Customs Union would essentially lie in greater access to the Russian market. Given that the Eurasian Union would bring free mobility of labor, it would, in theory, legalize the estimated up to two million Azerbaijani guest laborers in Russia, of which only a fraction have a legal presence—implying that Customs Union membership would remove one potential Russian instrument of pressure. -

Assault and Threats Against Members of the Institute for Peace and Democracy - AZE 002 / 0611 / OBS 090

www.fidh.org Azerbaijan 16 June 2011 Assault and threats against members of the Institute for Peace and Democracy - AZE 002 / 0611 / OBS 090 The Observatory has been informed by reliable sources about the assault and threats against Ms. Leyla Yunus, Director of the Institute for Peace and Democracy (IPD) and member of OMCT General Assembly, as well as against other members of IPD. The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, a joint programme of the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), requests your urgent intervention in the following situation in Azerbaijan. Description of the situation: According to the information received, on June 13, 2011, at around 3.40 p.m., an unknown man dressed in plainclothes got out of a car with the plate number 90HS366, which had stopped in front of IPD offices, in Baku, and insulted Ms. Leyla Yunus with harsh words as she and other IPD member were painting some words on the wall of the private-owned house where IPD offices are located[1]. Some IPD members and local residents came to the place after hearing the cries. The man told them that he was a police officer, but refused to produce any document. He went back to his car and drove away. Ms. Leyla Yunus called some embassies' representatives to alert them about the incident and asked them to come to IPD offices. Around 15 minutes later, several police officers from Police Station No. 21 of Nasimi District Department of Internal Affairs of Baku City entered IPD's offices and aggressively demanded the removal of the words written on the wall. -

AZERBAIJAN: Assessment May 2012 – October 2013

The Eastern Partnership Roadmap to the Vilnius Summit An assessment of the roadmap implementation by the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum, co-ordinated by the Regional Environmental Centre, Moldova, and PASOS – Policy Association for an Open Society, October 2013 AZERBAIJAN: Assessment May 2012 – October 2013 by Gubad Ibadoglu, Public Initiative Center, Araz Aslanli and Nazim Jafarov, Caucasus Strategic Analytical Center Participatory policymaking should be priority Azerbaijan has slipped behind other partner countries with slow progress on Association and Visa Facilitation and Readmission agreements Does the government engage with civil society on policymaking? No Is policymaking participatory, e.g. public consultations No on draft legislation? Does the government actively engage in trialogue with EU and civil society? No Is the process of drafting agreements between Azerbaijan and the EU transparent with public consultations? No Does the EU delegation actively engage in trialogue with government and civil society Partially Does the EU delegation promote trialogue talks with government and civil society? Yes Positive developments: • “Azerbaijan 2020: Look into the Future” development plans finalised • Working agreement signed between State Border Service and Frontex • Progress on Visa Facilitation and Readmission agreements – to be signed at Vilnius summit • Agreement on TAP (Trans Adriatic Pipeline) as partner on Southern Gas Corridor Negative developments: • Amendments to legislation on freedom of assembly further limit citizens’ -

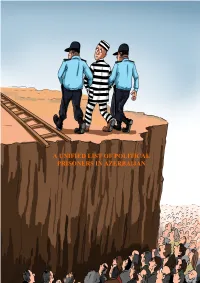

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 November 2019 Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 3 THE DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS ...................................................... 4 POLITICAL PRISONERS ............................................................................................ 5 A. JOURNALISTS AND BLOGGERS .................................................................... 5 B. POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ACTIVISTS .......................................................... 13 A case of financing of the opposition party ......................................................... 19 C. RELIGIOUS ACTIVISTS .................................................................................. 24 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and people arrested in Nardaran Settlement ............................................................................................................ 24 (2) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested together with him ....................................................................................................................... 51 (3) Other religious activists .................................................................................. 56 D. LIFETIME PRISONERS ................................................................................... 59 E. POLITICAL HOSTAGES ................................................................................ -

Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned

Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper October 31, 2005 Summary..................................................................................................................2 Background..............................................................................................................4 Past Elections ...................................................................................................... 5 Official Positions in the Lead-up to the 2005 Election Campaign ..........................6 Election Commissions .............................................................................................8 Voter Cards, IDs and Voter Lists.............................................................................8 Registration of Candidates.......................................................................................9 Media .....................................................................................................................10 Local Government Interference .............................................................................11 Candidates’ Meetings With Voters........................................................................11 Rallies ....................................................................................................................13 In the Capital, Baku........................................................................................... 13 In the Regions................................................................................................... -

Defamation and Insult Laws in the OSCE Region: a Comparative Study

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe The Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović Defamation and Insult Laws in the OSCE Region: A Comparative Study (Commissioned by the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media) March 2017 Author/Lead Researcher: Scott Griffen, Director of Press Freedom Programmes, International Press Institute Managing Editor: Barbara Trionfi, Executive Director, International Press Institute 1 About This Study This study examines the existence of criminal defamation and insult laws in the territory of the 57 participating States of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). In doing so, it offers a broad, comparative overview of the compliance of OSCE participating States’ legislation with international standards and best practices in the field of defamation law and freedom of expression. The primary purpose of the study is to identify relevant provisions in law. Although the study does include examples of the usage of these provisions, it is not an analysis of legal practice. Where prudent, the study provides basic information about national courts’ interpretation of the law insofar as is necessary to understand the objective component of the provision. However, due to constraints of time and resources, the study does not delve into court standards on application in any great detail. The study is divided into two sections. The first section offers conclusions according to each of the principal categories researched and in reference to international standards on freedom of expression. The second section provides the detailed research findings for each country, including relevant examples. As the study’s title suggests, the primary research category is general criminal laws on defamation and insult. -

Azerbaijan: Vulnerable Stability

AZERBAIJAN: VULNERABLE STABILITY Europe Report N°207 – 3 September 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. POLITICAL PORTRAIT OF THE REGIME ............................................................... 2 A. CONSOLIDATION OF ILHAM ALIYEV’S POWER ............................................................................. 2 1. Formation of a leader ................................................................................................................... 2 2. From clan politics to bureaucratic-oligarchy ............................................................................... 2 3. A one-man show .......................................................................................................................... 4 B. SEARCH FOR AN “AZERBAIJANI MODEL” ..................................................................................... 5 1. Cult of personality ........................................................................................................................ 5 2. Statist authoritarianism ................................................................................................................ 6 III. RELATIONS WITHIN THE RULING ELITE ............................................................. 7 A. POWER BALANCE WITHIN THE SYSTEM ...................................................................................... -

Report to the Azerbaijani Government on the Visit to Azerbaijan Carried Out

CPT/Inf (2018) 37 Report to the Azerbaijani Government on the visit to Azerbaijan carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 23 to 30 October 2017 The Azerbaijani Government has requested the publication of this report and of its response. The Government’s response is set out in document CPT/Inf (2018) 38. Strasbourg, 18 July 2018 Note: In accordance with Article 11, paragraph 3, of the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, certain names have been deleted. - 3 - CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................4 I. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................7 A. Dates of the visit and composition of the delegation, context of the visit and establishments visited ...............................................................................................................7 B. The report and the follow-up ...................................................................................................8 C. Consultations held by the delegation and co-operation received .........................................9 D. The ongoing Article 10, paragraph 2, procedure...................................................................9 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT AND ACTION PROPOSED ..............................12 A. Law -

The Functioning of Democratic Institutions in Azerbaijan

Doc. 12270 31 May 2010 The functioning of democratic institutions in Azerbaijan Report 1 Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the Council of Europe (Monitoring Committee) Co-rapporteurs: Mr Andres HERKEL, Estonia, Group of the European People’s Party, and Mr Joseph DEBONO GRECH, Malta, Socialist Group Summary Several months ahead of the 10 th anniversary of the country’s membership in the Council of Europe, the Monitoring Committee considers that the democratic credibility of Azerbaijan is again at stake at its November 2010 parliamentary elections. It considers that these elections are particulary important in a country in which it is still necessary to reinforce the application in practice of the constitutionally guaranteed principle of the separation of powers and, especially, to strengthen the parliament’s role vis-à-vis the executive. Therefore, the Committee calls on the authorities to ensure the necessary conditions for the full compliance of the November parliamentary elections with European standards and to pass on a clear message at the highest political level, that electoral fraud will not be tolerated. It also urges all political parties to take part in the forthcoming elections. Furthermore, as regards the situation of media and journalists, the Committee condemns the arrests, intimidation and harrassment of journalists, it calls for decriminisation of defamation and for the release of Eynulla Fatullayev immediately as ordered by the European Court of Human Rights. 1 Reference to committee : Resolution 1115 (1997). F – 67075 Strasbourg Cedex | e-mail: [email protected] | Tel: + 33 3 88 41 2000 | Fax: +33 3 88 41 2733 Doc. -

Azerbaijan: Media, the Presidential Elections and the Aftermath

Azerbaijan: Media, the Presidential Elections and the Aftermath Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper August 4, 2004 Summary......................................................................................................................................... 2 General Media Environment........................................................................................................... 2 Violence against and Harassment of Journalists during the Presidential Election, October 2003 . 4 Government Response................................................................................................................. 8 Media Environment Since the Elections......................................................................................... 9 Economic Pressures and Government Control of Resources...................................................... 9 Civil Libel Suits ........................................................................................................................ 10 Drop in Circulation and Closures.............................................................................................. 12 Chap Evi Printing Press Case.................................................................................................... 12 Television.................................................................................................................................. 14 Access to Information ............................................................................................................... 15 Journalists’