12 Azerbaijan: Going It Alone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Republic of Azerbaijan Country Report

NCSEJ Country Report Email: [email protected] Website: NCSEJ.org Azerbaijan Zaqatala Quba Shaki Shabran Siazan Shamkir Mingachevir Ganja Yevlakh Sumqayit Hovsan Barda Baku Agjabedi Imishli Sabirabad Shirvan Khankendi Salyan Jalilabad Nakhchivan Lankaran m o c 60 km . s p a m - d 40 mi © 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 3 Azerbaijan is secular republic. Approximately 93% of the country’s inhabitants have an Islamic background. About 5% are Christian. The remainder of the population belongs to various religions. Around 30,000 Jews live in Azerbaijan. History ........................................................................................................................................... 4 The Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, also known as Azerbaijan People's Republic or Caucasus Azerbaijan in diplomatic documents, was the third democratic republic in the Turkic world and Muslim world, after the Crimean People's Republic and Idel-Ural Republic. Found in May 28, 1918 by Mahammad Amin Rasulzadeh. Ganja city was the Capital of Azerbaijan People’s Republic. Domestic Affairs ............................................................................................................................. 5 Azerbaijan is a constitutional republic with executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The executive branch dominates and there is no independent judiciary. The President and the National Assembly are elected -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2

No. 114 March 2020 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html FORMAL AND INFORMAL POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS Special Editors: Farid Guliyev and Lusine Badalyan (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus 2 ■■Post-Velvet Transformations in Armenia: Fighting an Oligarchic Regime 3 By Nona Shahnazarian (Institute for Archaeology and Ethnography at the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan) ■■Formal-Informal Relations in Azerbaijan 7 By Farid Guliyev (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■From a Presidential to a Parliamentary Government in Georgia 11 By Levan Kakhishvili (Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences, Germany) Research Centre Center Center for Eastern European German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies CRRC-Georgia East European Studies Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University of Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2 Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus Over the past decade, the three republics of the South Caucasus made changes to their constitutions. Georgia shifted from presidentialism to a dual executive system in 2012 and then, in 2017, amended its constitution to transform into a European-style parliamentary democracy. In Armenia, faced with the presidential term limit, the former President Sargsyan initiated constitutional reforms in 2013, which in 2015 resulted in Armenia’s moving from a semipresidential system to a parliamentary system. While this allowed the incumbent party to gain the majority of seats in the April 2017 parliamentary election and enabled Sargsyan to continue as a prime minister, the shift eventually backfired, spilling into a mass protest, the ousting of Sargsyan from office, and the victory of Nikol Pashinyan’s bloc in a snap parliamentary election in December 2018. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

Synergetics of the Language, National Consciousness and Culture by Globalization

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 5, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Synergetics of the Language, National Consciousness and Culture by Globalization Nigar Chingiz Veliyeva1 1 Azerbaijan University of Languages, Baku, Azerbaijan Correspondences: Nigar Chingiz Veliyeva, Azerbaijan University of Languages, Baku, Azerbaijan. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 15, 2015 Accepted: April 10, 2015 Online Published: May 30, 2015 doi:10.5539/ijel.v5n3p154 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v5n3p154 Abstract The main aim of the investigation is to learn out all positive and negative influences of the process of globalization on the formation and development of the national language, national consciousness and national culture in the modern world during the intercultural communication and to analyze the power and impact of the Modern English as a global language to our national Azerbaijani language. To study such a global problem from the different view points as of native, so foreign scientists is also one of the main aims. The process of globalization, covering various spheres of life, is universal, as for thousands of years separated, remote to some extent, differential events—national or regional peculiarities, habits, complexes strongly influenced by modern technologies, approaching each other with incredible speed and combine as a result of multifaceted economic, socio-political, moral and ideological ties, limiting the kind of peculiarities, lead to the events and processes happening in the world. It is obvious that there is a great influence on the language’s enrichment of the process of globalization, which had taken place in the world. -

Review Article

Ashdin Publishing Journal of Drug and Alcohol Research Vol. 10 (2021), Article ID 23612, 04 pages Review Article Relno Situation Foreign Economic Relations and Geopolitical Perspective Azerbaijan Z.H.Aliyev*1 Dr.D.I.Allaxverdiyev2 1Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan Address Correspondence to: ZH Aliyev, Professor, Institute of Soil Science and Agrochemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan; E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 11, 2021; Accepted: April 25, 2021; Published: May 4, 2021 Copyright: © 2021 Aliyev. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract “natural resources, ill-conceived, irrational and ill-use, op- The purpose of research is to identify the prospects for foreign economic eration as a result of their destruction, leading the world to relations and sustainable development of the geopolitical interests of the destruction leads and so prosperous development our econ- world, an increase in foreign investment, the development of competitive omy, and is the cause of sustainable artımaına exposure national wealth, disclosure and recreate the real picture of foreign eco- nomic relations. Given the increase in the rate of development of diplo- over time, adverse effects on future generations, “he said. matic and economic relations between the countries of the world deter- mines the need for the creation of new forms of foreign economic relations Theodore Roosevelt approach to the controversial event in of Azerbaijan. -

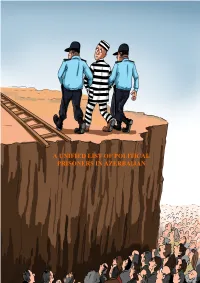

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Eap CSF Roadmap Report Overview 13 Nov 2013

THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP ROADMAP TO THE VILNIUS SUMMIT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ROADMAP IMPLEMENTATION BY THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM This project is funded by the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP ROADMAP TO THE VILNIUS SUMMIT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ROADMAP IMPLEMENTATION BY THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM MAY 2012 – OCTOBER 2013 An Open Road from Vilnius to Riga by Jeff Lovitt, Executive Director, PASOS ...................................................................................... 3 ARMENIA: Association Agreement stopped in its tracks by Boris Navasardian, Yerevan Press Club President, Arevhat Grigoryan, Yerevan Press Club Expert, Mikayel Hovhannisyan, Europe Program Manager with Eurasia Partnership Foundation, Heriknaz Harutyunyan, Yerevan Press Club Expert ....................................................................... 7 AZERBAIJAN: Participatory policymaking should be priority by Gubad Ibadoglu, Public Initiative Center, Araz Aslanli and Nazim Jafarov, Caucasus Strategic Analytical Center ...................................... 21 BELARUS: Dialogue limited to technical and diplomatic level by Andrei Yahorau, Center for European Transformation ............................................................ 35 GEORGIA: Civil society gains greater say in policymaking by Tamara Pataraia, Manana Kochladze, Tamar Khidasheli, Kakha Gogolashvili ...................... -

The Two Faces of Azerbaijan's Mr. Aliyev

The Opinion Pages | EDITORIAL The Two Faces of Azerbaijan’s Mr. Aliyev By THE EDITORIAL BOARD JAN. 11, 2015 President Ilham Aliyev of Azerbaijan does a masterful political Jekyll and Hyde. A cable from the American ambassador to Baku released on WikiLeaks described him as a Michael Corleone-Sonny Corleone figure — referring, respectively, to the coolly calculating and the impetuously violent brothers of the “Godfather” mafia family. Mr. Aliyev is “pro-Western” in many of the ways the West admires: He is suave, well dressed and well spoken in English; he is ready to send his country’s ample supplies of oil and gas to Europe and to Israel; his Islam is moderate and modern; and he hosts lavish international events like the Eurovision Song Contest in 2012 and the European Games to be held next June. He is also hugely corrupt, and his authoritarian regime has one of the world’s worst records on human rights. Last month, continuing a crackdown on independent media and nongovernmental organizations, police officers raided the offices of the United States-financed Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty in Baku — known locally as Radio Azadliq — taking away computers and documents and sealing the premises. A dozen R.F.E./R.L. employees were detained and questioned. A few weeks earlier, the government jailed a well-known investigative reporter, Khadija Ismayilova, who had worked for the broadcaster and had reported on the lucrative business dealings of Mr. Aliyev’s family. The government first tried to frighten and blackmail her, then hit her with the Orwellian charge that she had pushed a lover toward suicide. -

Dr. Kaush Arha Senior Advisor for Strategic Engagement, United States Agency for International Development (Usaid)

FORUM SPEAKERS H.E. NOVRUZ MAMMADOV PRIME MINISTER OF AZERBAIJAN Mr. Novruz Mammadov was appointed Prime Minister of Azerbaijan in April 2018. Prior to his appointment, Mr. Mammadov was serving as an Assistant to the President of Azerbaijan on foreign issues as well as serving as Head of the Department of Lexicology and Stylistics of the French Language at the Azerbaijan University of Languages. Previously, Mr. Mammadov has served as a senior interpreter in Algeria and Guinea, Dean of Preparatory Faculty and Dean of Faculty of the French Language at the Azerbaijan Pedagogical Institute of Foreign Languages, Head of the Foreign Relations Department of the Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan, and interpreter to former President of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev. He was granted the rank of Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Ambassador by the decree of the President of Azerbaijan in January 2002 and in September 2005, Mr. Mammadov became a member of the National Commission of the Republic of Azerbaijan for UNESCO. Mr. Mammadov has received a number of honors including the French Legion d’Honneur Order by former French President Jacques Chirac, the Order of the Legion of Honor of Poland by former Polish President Lech Kaczyński, and the Order of Glory (Shohrat) by the decree of the President of Azerbaijan. MR. ELDAR ABAKIROV DEPUTY MINISTER OF ECONOMY OF KYRGYZSTAN Eldar Abakirov is Deputy Minister of Economy of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan and a Board Member of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Kyrgyzstan. From 2010-11 he worked as an expert at the National Bank of Kyrgyzstan and from 2003-10 he held several positions including Chief Specialist to the Deputy Director of the Treasury Department at JSC Bank Center Credit in Almaty, Kazakhstan. -

Country – Fact Sheet

Country – Fact Sheet General Official Name Republic of Azerbaijan Capital Baku Area 86,600 km2 Currency AZN (Manat) GDP AZN 70.13 billion (US $41.25 billion) [2017] GDP Growth Rate 0.1 % (2017) Unemployment 6% [2016 est.] GDP Per Capita AZN 7091 (US$4171) [2017] GDP Per Capita (PPP) US$ 17500 (2016 est.) Forest Cover 11.3% CO2 emissions 38 million Mt (2015 est.) Tourist Arrivals 2.69 million (2017) Population 10 million [2017] 9.95 million as on 1st September 2018 Population growth rate: 0.80 % Age Profile 0-14 years: 22.95% 15-24 years: 14.84% 25-54 years: 45.39% 55-64 years: 10.17% 65 years and over: 6.64% Life expectancy Total 72.8 years: Male: 69.7 years & Female: 76.1 years [2017 est.] Languages Azerbaijani (Azeri) (official) 92.5%, Russian 1.4%, Armenian 1.4%, other 4.7% (2009 est.) Ethnic groups Azerbaijani 91.6%, Lezgian 2%, Russian 1.3%, Armenian 1.3%, Talysh 1.3%, other 2.4% Religion Shia Muslim: 70%, Sunni Muslim: 23%, Russian Orthodox: 2.5%, Armenian Orthodox: 2.3%,others: 1.8% Internet Penetration 78.2% of population (2016 est.) Mobile phones 10.6 million Urbanisation urban population: 55.2% of total population (2017) Page 1 Exports US$ 13.81 billion [2017] Imports US$ 8.78 billion [2017] Main Trade Partners Italy, Turkey, Russia, China, Germany, Ukraine, USA (2017) Political Political Structure Presidential democracy with a directly elected President, who has a five year term. President appoints First Vice President and other Vice Presidents. Presidents appoints Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers to run the government. -

GORUS-2010 (ENG) .Indd

1 Ramiz Mehdiyev Academician National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan GORIS - 2010: SEASON OF THEATRE OF THE ABSURD THE HISTORY OF OCCUPIED NAGORNO-KARABAKH AND THE BATTLE FOR JUSTICE TBILISI - 2010 2 Ramiz Mehdiyev | THE HISTORY OF OCCUPIED NAGORNO-KARABAKH AND THE BATTLE FOR JUSTICE 3 ISBN: 978-9941-17-161-1 ISBN: 978-9941-17-162-8 Copyright © by Ramiz Mehdiyev All rights reserved Printed in Georgia First Edition No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Universal Publishing House, or under terms agreed with the author. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the author. Publishing House “UNIVERSAL” Tel: 22 36 09 8(99) 17 22 30 E-mail: [email protected] Address: 19 Chavchavadze ave. 0179 Tbilisi Ramiz Mehdiyev | GORIS - 2010: SEASON OF THEATRE OF THE ABSURD Tbilisi, 2010, 88+1p.sh. maps. In his book, full member of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Science, outstanding philosopher and scientist, Ramiz Mehdiyev, uses scientifi c evidence to reveal the falsifi cation of history by Armenia’s leaders, who attempt to confuse the international public with new lies. He draws attention to the historical evidence that the Armenian state was established on territory which was formerly Azerbaijani land. The academician replies in his book to the new ‘research’ of Armenian idealogues with fi rm scientifi c evidence, and proves the fultility and baselessness of those ‘ideas’ and that ‘research’.