Azerbaijan: Media, the Presidential Elections and the Aftermath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2

No. 86 25 July 2016 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html TURKISH SOCIETAL ACTORS IN THE CAUCASUS Special Editors: Andrea Weiss and Yana Zabanova ■■Introduction by the Special Editors 2 ■■Track Two Diplomacy between Armenia and Turkey: Achievements and Limitations 3 By Vahram Ter-Matevosyan, Yerevan ■■How Non-Governmental Are Civil Societal Relations Between Turkey and Azerbaijan? 6 By Hülya Demirdirek and Orhan Gafarlı, Ankara ■■Turkey’s Abkhaz Diaspora as an Intermediary Between Turkish and Abkhaz Societies 9 By Yana Zabanova, Berlin ■■Turkish Georgians: The Forgotten Diaspora, Religion and Social Ties 13 By Andrea Weiss, Berlin ■■CHRONICLE From 14 June to 19 July 2016 16 Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 86, 25 July 2016 2 Introduction by the Special Editors Turkey is an important actor in the South Caucasus in several respects: as a leading trade and investment partner, an energy hub, and a security actor. While the economic and security dimensions of Turkey’s role in the region have been amply addressed, its cross-border ties with societies in the Caucasus remain under-researched. This issue of the Cauca- sus Analytical Digest illustrates inter-societal relations between Turkey and the three South Caucasus states of Arme- nia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, as well as with the de-facto state of Abkhazia, through the prism of NGO and diaspora contacts. Although this approach is by necessity selective, each of the four articles describes an important segment of transboundary societal relations between Turkey and the Caucasus. -

Bosnian Muslim Reformists Between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914 Harun Buljina

Empire, Nation, and the Islamic World: Bosnian Muslim Reformists between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914 Harun Buljina Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Harun Buljina All rights reserved ABSTRACT Empire, Nation, and the Islamic World: Bosnian Muslim Reformists between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1901-1914 Harun Buljina This dissertation is a study of the early 20th-century Pan-Islamist reform movement in Bosnia-Herzegovina, tracing its origins and trans-imperial development with a focus on the years 1901-1914. Its central figure is the theologian and print entrepreneur Mehmed Džemaludin Čaušević (1870-1938), who returned to his Austro-Hungarian-occupied home province from extended studies in the Ottoman lands at the start of this period with an ambitious agenda of communal reform. Čaušević’s project centered on tying his native land and its Muslim inhabitants to the wider “Islamic World”—a novel geo-cultural construct he portrayed as a viable model for communal modernization. Over the subsequent decade, he and his followers founded a printing press, standardized the writing of Bosnian in a modified Arabic script, organized the country’s Ulema, and linked these initiatives together in a string of successful Arabic-script, Ulema-led, and theologically modernist print publications. By 1914, Čaušević’s supporters even brought him to a position of institutional power as Bosnia-Herzegovina’s Reis-ul-Ulema (A: raʾīs al-ʿulamāʾ), the country’s highest Islamic religious authority and a figure of regional influence between two empires. -

Azerbaijan: Emerging Market

NEWHORIZON Shawwal–Dhu Al Hijjah 1429 COUNTRY FOCUS Azerbaijan: emerging market With a long history of secularism, Azerbaijan has not been prominent in the Islamic world, despite being essentially a Muslim state, with around 95 per cent of the 8.5 million population Muslim. Can this oil-rich state on the shores of the Caspian Sea be put on the map of Islamic finance? Renat Bekkin, PhD in Law, senior researcher at the Institute for African Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, reports from the country’s capital, Baku. Like many other former republics of the the time of ADR’s emergence, Musavat’s country’s social and political life. The key USSR, for a few years after the October opposition, an Islamist party called Ittihad partner of modern Azerbaijan is Turkey, (Soviet) Revolution of 1917 Azerbaijan (Arabic word for ‘alliance, union’), was which advocates the principles of was an independent state. Azerbaijanis against the creation of ADR. The ideologists secularism, and not its other neighbour, are proud that the Azerbaijani Democratic of Ittihad were true pan-Islamists and Iran, despite the fact that the overwhelming Republic (ADR), declared in 1918, became therefore were calling for the unification of majority of Azerbaijani and Iranian the first secular state in the region, a few all Muslim nations of the Russian Empire Muslims share the same denomination of years prior to abolition of the caliphate in and against the concept of the nation state Islam – Shia. Turkey. At that time, the ADR was a classic of Azerbaijanis, or ‘Transcaucasian Tatars’, parliamentary republic. -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2

No. 114 March 2020 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html FORMAL AND INFORMAL POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS Special Editors: Farid Guliyev and Lusine Badalyan (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus 2 ■■Post-Velvet Transformations in Armenia: Fighting an Oligarchic Regime 3 By Nona Shahnazarian (Institute for Archaeology and Ethnography at the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan) ■■Formal-Informal Relations in Azerbaijan 7 By Farid Guliyev (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■From a Presidential to a Parliamentary Government in Georgia 11 By Levan Kakhishvili (Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences, Germany) Research Centre Center Center for Eastern European German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies CRRC-Georgia East European Studies Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University of Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2 Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus Over the past decade, the three republics of the South Caucasus made changes to their constitutions. Georgia shifted from presidentialism to a dual executive system in 2012 and then, in 2017, amended its constitution to transform into a European-style parliamentary democracy. In Armenia, faced with the presidential term limit, the former President Sargsyan initiated constitutional reforms in 2013, which in 2015 resulted in Armenia’s moving from a semipresidential system to a parliamentary system. While this allowed the incumbent party to gain the majority of seats in the April 2017 parliamentary election and enabled Sargsyan to continue as a prime minister, the shift eventually backfired, spilling into a mass protest, the ousting of Sargsyan from office, and the victory of Nikol Pashinyan’s bloc in a snap parliamentary election in December 2018. -

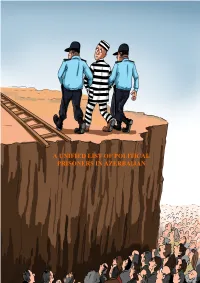

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Eap CSF Roadmap Report Overview 13 Nov 2013

THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP ROADMAP TO THE VILNIUS SUMMIT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ROADMAP IMPLEMENTATION BY THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM This project is funded by the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors, and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP ROADMAP TO THE VILNIUS SUMMIT AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ROADMAP IMPLEMENTATION BY THE EASTERN PARTNERSHIP CIVIL SOCIETY FORUM MAY 2012 – OCTOBER 2013 An Open Road from Vilnius to Riga by Jeff Lovitt, Executive Director, PASOS ...................................................................................... 3 ARMENIA: Association Agreement stopped in its tracks by Boris Navasardian, Yerevan Press Club President, Arevhat Grigoryan, Yerevan Press Club Expert, Mikayel Hovhannisyan, Europe Program Manager with Eurasia Partnership Foundation, Heriknaz Harutyunyan, Yerevan Press Club Expert ....................................................................... 7 AZERBAIJAN: Participatory policymaking should be priority by Gubad Ibadoglu, Public Initiative Center, Araz Aslanli and Nazim Jafarov, Caucasus Strategic Analytical Center ...................................... 21 BELARUS: Dialogue limited to technical and diplomatic level by Andrei Yahorau, Center for European Transformation ............................................................ 35 GEORGIA: Civil society gains greater say in policymaking by Tamara Pataraia, Manana Kochladze, Tamar Khidasheli, Kakha Gogolashvili ...................... -

Turkey's Gülen Controversy Spills Over to Azerbaijan

6/23/2014 Turkey's Gülen Controversy Spills over to Azerbaijan WEDNESDAY, 02 APRIL 2014 Turkey's Gülen Controversy Spills over to Azerbaijan Published in Field Reports By Mina Muradova (04/02/2014 issue of the CACI Analyst) The conflict between Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the Islamic Hizmet movement’s leader Fethullah Gülen has spread to Azerbaijan. A scandal erupted in Turkey in December 2013, when police arrested 52 suspects on various corruption charges, including the sons of three government ministers and the general manager of the state-owned Halkbank. The operation detained people close to the Turkish Prime Minister. Erdogan termed it a plot by the Hizmet movement and its exiled leader Gülen to overthrow the government. It was considered a response to the government’s decision last November to close in 2015 the dershane, a network of private tutoring centers, most of which are run by the Gülen movement. Educational centers reportedly provide enormous financial resources to the group but also help it recruit new members and allies in government. In late February, both government and opposition media reported that a similar “parallel structure” existed in Azerbaijan. The diplomatic missions of both countries reportedly provided the government with a list of local Gülen followers. In early March, emails showing ties between Azerbaijani officials and Gülen were leaked to the media. One of them was related to Elnur Aslanov, an official of President Ilham Aliyev's Administration. “The Turkish government is concerned that the Hizmet movement is expanding in Azerbaijan through its wide network of educational establishments and businesses, as well as by placing figures loyal to the Hizmet movement in high-level posts in government,” the Musavat daily reported on February 28. -

Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política Y Valores. Http

1 Revista Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores. http://www.dilemascontemporaneoseducacionpoliticayvalores.com/ Año: VII Número: Edición Especial Artículo no.:102 Período: Octubre, 2019. TÍTULO: Las direcciones en el desarrollo del estudio de prensa en Azerbaiyán: contexto histórico y social. AUTOR: 1. Ph.D. Garanfil Guliyeva Dunyamin. RESUMEN: El artículo se centa en el contexto histórico y social de la historia de la prensa de Azerbaiyán, y examina las direcciones en el desarrollo de la prensa. Identifica la tendencia actual en un contexto histórico y social hacia el desarrollo de la prensa. Se están analizando las etapas actuales de las direcciones de desarrollo. Durante el período 1900-2000, se siguen los cambios de período en el desarrollo de la prensa, la dinámica y los antecedentes sociales, y los factores deficiencias actuales que afectan el desarrollo de la prensa, incluidos los efectos del "régimen post- soviético" y "la influencia de los mecanismos de los extraterrestres", elementos que son llevados al centro de atención. El artículo incorpora principios de investigación de vanguardia para aclarar el panorama científico-teórico en el campo del estudio de prensa azerbaiyano. PALABRAS CLAVES: Estudio de prensa azerbaiyano, la era moderna, direcciones de desarrollo, historia y contexto social. TİTLE: The directions in the development of the press study in Azerbaijan: historical and social context. 2 AUTHOR: 1. Ph.D. Garanfil Guliyeva Dunyamin. ABSTRACT: The article focuses on the historical and social context of Azerbaijan's press history, and examines directions in press development. It identifies the current tendency in a historical and social context towards the development of press. -

Pen International Writers in Prison Committee Caselist

PEN INTERNATIONAL WRITERS IN PRISON COMMITTEE CASELIST January-December 2013 PEN International Writers in Prison Committee 50/51 High Holborn London WC1V 6ER United Kingdom Tel: + 44 020 74050338 Fax: + 44 020 74050339 e-mail: [email protected] web site: www.pen-international.org PEN INTERNATIONAL CHARTER The P.E.N. Charter is based on resolutions passed at its International Congresses and may be summarised as follows: P.E.N. affirms that: 1. Literature knows no frontiers and must remain common currency among people in spite of political or international upheavals. 2. In all circumstances, and particularly in time of war, works of art, the patrimony of humanity at large, should be left untouched by national or political passion. 3. Members of P.E.N. should at all times use what influence they have in favour of good understanding and mutual respect between nations; they pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world. 4. P.E.N. stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong, as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. P.E.N. declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world towards a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. -

The Positions of Political Parties and Movements in Azerbaijan on The

The Positions of Political Parties and Movements in Azerbaijan on the Resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict The Positions of Political Parties and Movements in Azerbaijan on the Resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Bakhtiyar Aslanov and Sevinj Samedzadeh 1 The Positions of Political Parties and Movements in Azerbaijan on the Resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict This publication has been produced in the framework of the project “Joint Platform for Realistic Peace in the South Caucasus” of the Imagine Center for Conflict Transformation in partnership with the Center for Independent Social Research – Berlin. The Imagine Center is an independent, non-political organization that is dedicated to positively transforming relations and laying foundations for lasting and sustainable peace in conflict-torn societies. www.imaginedialogue.com, [email protected] The Center for Independent Social Research – Berlin (CISR-Berlin) is a non-governmental organization focused on social research, civil society development and education in cooperation with Eastern Europe and post-Soviet states. www.cisr-berlin.org, [email protected] The project “Joint Platform for Realistic Peace in the South Caucasus” is funded by ifa (Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen) / Funding program zivik with resources provided by the German Federal Foreign Office. 2 The Positions of Political Parties and Movements in Azerbaijan on the Resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict THE POSITIONS OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND MOVEMENTS IN AZERBAIJAN ON THE RESOLUTION OF THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH CONFLICT ................................ 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 4 Prioritization of Nagorno-Karabakh in the Agenda of the Parties and Movements ................ 5 Policies Regarding Relations with Armenia and the Resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict ................................................................................................................................. -

PNABZ770.Pdf

I • • I • I • • • • COMPENDIUM OF STATEMENTS FROM POLITICAL PARTIES ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL REFERENDUM AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS • OF NOVEMBER 12, 1995 REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN • • COMPENDIUM OF STATEMENTS FROM POLITICAL PARTIES ON THE CONSTITUTIONAL REFERENDUM AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS OF NOVEMBER 12, 1995 REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN December 15, 1995 • • • • • (THE BALLOT) A3aPBAJ'i.AH PECIIYBJIBKACLI MHJIJIII MaltlJIHCHHa CE'IKwi9P.n;a '"tJ'.ox~TJibl ~H .nfuaciI Y3Pa ·cacBEPM:a yqm - ·. .. CEqKH 6YJIJIETEHH ··12· BOja6p 1995-Q HJI ~PSA.NAH lE.\\OKPATHK OCTBfJIAJI UAPTHJACbl 1aJU1<1>5A CblPACbl HJla) A..'gp6AJ~AH .lf.'i110KPAT CAhR6KAP JIAP flAPTHJACbl ~3aP6AJ'ofAH ,\\HJIJIH l168JldT'IHJl.HK IlAPTHJACbl n..1.1P6AJ'UH MHJUIH HCTHrJIAJI DAPTHJACbl ~~P6AJ't\H HAMHffd A.. 'IJARC• DAPTHJACbl ~~ .~~AJ'IAH XAJJf 'ld6hdCH DAPTHJACbl JJll g'Jdff DAPTHJAChl • Bl AJaP&AJ'IAH DAPTHJACli . ·-. .. .. caCBEP1'"a ~AMA.HY.5H.P.il31f 'IOX CHJA.CJI. llAPTHJAHblH (elt.l:.V.11' nU'f11JiUIAP 1iJIOK>'H¥ff;) • • i\llbl Hbfff CAXiiJA°R.lllllflil 6YJIJl'ETEH· E'T116APClitJ.. CAJblJI blP • • National Democratic Institute For International Affairs conducting nonpartisan international programs to help promote, maintain and strengthen democratic institutions 1717 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Fifth Floor Washington, DC 20036 (202) 328-3136 FAX (202) 939-3166 E-MAIL: [email protected] Chairman Paul G. Kirk, Jr. The National Democratic Institute for International Affairs (NDI) is a Vice Chair Rachelle Horowitz nongovernmental and nonprofit organization conducting nonpartisan international Secretary programs to promote and strengthen democratic institutions around the world. Kenneth F. Melley Working with political parties, civic organizations and parliaments, NDI has Treasurer Hartina Flournoy sponsored political development projects in more than 60 countries. -

The Turkey-Armenia-Azerbaijan Triangle: the Unexpected Outcomes of the Zurich Protocols Zaur SHIRIYEV* & Celia DAVIES** Abstract Key Words

The Turkey-Armenia-Azerbaijan Triangle: The Unexpected Outcomes of the Zurich Protocols Zaur SHIRIYEV* & Celia DAVIES** Abstract Key Words This paper analyses the domestic and regional Zurich Protocols, Turkish-Armenian impact of the Turkish-Armenian normalisation rapprochement/normalisation, Russo- process from the Azerbaijani perspective, with Georgian War, Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, a focus on the changing dynamic of Ankara- Azerbaijani-Turkish relations. Baku relations. This line of enquiry is informed by international contexts, notably the 2008 Russian-Georgian war and the respective roles Introduction of the US and Russia. The first section reviews the changed regional dynamic following two regional crises: the August War and the Turkish- Between 2008 and 2009, Azerbaijan’s Armenian rapprochement. The second section foreign policy was thrown into a state analyses domestic reaction in Azerbaijan among of crisis. The Russo-Georgian War in political parties, the media, and the public. The third section will consider the normalisation August 2008 followed by the attempted process, from its inception through to its Turkish-Armenian rapprochement suspension. The authors find that the crisis in process (initiated in September 2008) Turkish-Azerbaijani relations has resulted in an intensification of the strategic partnership, unsettled geopolitical perspectives across concluding that the abortive normalisation the Caucasus and the wider region, process in many ways stabilised the pre-2008 throwing traditionally perceived axes status quo in terms of the geopolitical dynamics of the region. of threats and alliances into question. Before the dust had settled on the first conflict, another was already brewing, * Zaur Shiriyev is a foreign policy analyst based destabilising many of Azerbaijan’s in Azerbaijan, a columnist for Today’s Zaman, basic foreign policy assumptions.