CDDRL Number 89 WORKING PAPERS September 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statement by H.E. Mr. Ilham Aliyev, President of The

STATEMENT BY H.E. MR. ILHAM ALIYEV, PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN MEETING OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT “FINANCING THE 2030 AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE ERA OF COVID-19 AND BEYOND” 29 September 2020 Mr. Secretary-General, Distinguished Heads of State and Government, Azerbaijan attaches great importance to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Our success was reflected in the “Sustainable Development Report 2020”, where Azerbaijan ranks 54th among 166 countries in the Sustainable Development Goals Index. Azerbaijan’s GDP tripled in the last 17 years. The external public debt of Azerbaijan is one of the lowest in the world. Azerbaijan has the lowest external debt among the oil exporting countries. Foreign Exchange Reserves of Azerbaijan exceed the external public debt by 6 times. Azerbaijan places a special emphasis on the equal distribution of energy revenues between current and the future generations. To this end, the State Oil Fund was established. The assets of the Fund currently exceed the GDP of the country. Azerbaijan has achieved one of the highest income equality levels. As a result of the Armenian occupation more than 1 million Azerbaijanis became refugees and internally displaced persons. About 8 billion Azerbaijani manats amounting to nearly 5 billion USD has been allocated for addressing needs of this vulnerable group. Azerbaijan itself became a donor country. Overall, Azerbaijan provided financial and humanitarian assistance to nearly 120 countries during the last 15 years. Despite the decrease in the state revenues during the pandemic period the government has allocated fund around 3% of GDP to the protection of jobs, economic growth and the public health. -

1 to the PRESIDENT of the AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC Mr

TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE AZERBAIJAN REPUBLIC Mr. HEYDAR ALIYEV* Dear Heydar Aliyevich, According to the exchange of views on the issues of strengthening the ceasefire regime, which took place in Baku, I am sending to you, as it was agreed, the proposals of the Minsk Conference co- chairmen. The proposals of the mediator on strengthening the ceasefire in the Nagorno Karabakh conflict On behalf of the Co-chairmanship of the OSCE Minsk Conference (hereinafter – the Mediator), with the purpose of strengthening the ceasefire regime established in the conflict region since May 12, 1994 and creating more favourable conditions for the progress of the peace process, we jointly suggest that the conflicting sides (hereinafter – the Sides) should assume the following obligations: 1. In the event of incidents threatening the ceasefire, to immediately inform the other Side (and in a copy – the Mediator) in written form by facsimile or by the PM line with an exact specification of the place, time and character of the incident and its consequences. The other Side is informed that measures are being taken for non-admission of reciprocal actions which could lead to the aggravation of the incident. Accordingly, the other Side is expected to take appropriate measures immediately. If possible, proposals about taking urgent measures to overcome this incident as quickly as possible and restore the status quo ante are also reported. 2. Upon receiving such a notification from the other Side, to immediately check the facts and give a written response not later than within 6 hours (in a copy – to the Mediator). -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2

No. 114 March 2020 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html FORMAL AND INFORMAL POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS Special Editors: Farid Guliyev and Lusine Badalyan (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus 2 ■■Post-Velvet Transformations in Armenia: Fighting an Oligarchic Regime 3 By Nona Shahnazarian (Institute for Archaeology and Ethnography at the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, Yerevan) ■■Formal-Informal Relations in Azerbaijan 7 By Farid Guliyev (Justus Liebig University Giessen) ■■From a Presidential to a Parliamentary Government in Georgia 11 By Levan Kakhishvili (Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences, Germany) Research Centre Center Center for Eastern European German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies CRRC-Georgia East European Studies Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich University of Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 114, March 2020 2 Introduction by the Special Editors The Interplay of Formal and Informal Institutions in the South Caucasus Over the past decade, the three republics of the South Caucasus made changes to their constitutions. Georgia shifted from presidentialism to a dual executive system in 2012 and then, in 2017, amended its constitution to transform into a European-style parliamentary democracy. In Armenia, faced with the presidential term limit, the former President Sargsyan initiated constitutional reforms in 2013, which in 2015 resulted in Armenia’s moving from a semipresidential system to a parliamentary system. While this allowed the incumbent party to gain the majority of seats in the April 2017 parliamentary election and enabled Sargsyan to continue as a prime minister, the shift eventually backfired, spilling into a mass protest, the ousting of Sargsyan from office, and the victory of Nikol Pashinyan’s bloc in a snap parliamentary election in December 2018. -

Political Leadership After Communism

POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AFTER COMMUNISM TIMOTHY J. COLTON MORRIS AND ANNA FELDBERG PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT AND RUSSIAN STUDIES, HARVARD UNIVERSITY Abstract: Political scientists have paid little attention to the role of leadership. This article suggests a way to think systematically about leaders’ contributions in the former Soviet Union by examining their ability to achieve their own goals and the impact they have. The fifteen countries provide a wide range of variation on the dependent variable. hat have we learned about political leadership in the post-communist Wworld? It is fair to say that it is not as much as we have picked up about a host of other ordering issues, among them political economy, institutional design, ethnic conflict, and public opinion and elections. Considering the significance of the magnitude of the topic, we have not learned nearly enough. There are students of post-communist politics who tend to accept the importance of the theme and those who, embracing structural approaches, tend not to. A majority in the scholarly community fall into the former camp. “Leadership matters,” is how they often put it. “It matters a lot. Why, just look at Gorbachev’s role, and also Yeltsin’s, and then there is Putin, and [fill in the blanks].” However, the majority have seldom thought leadership important enough to make it a primary object of their research. Leaders have figured in a handful of serious political biographies, in natu- ralistic roles in many studies of other topics, in several studies of ideas in politics, and in all manner of op-eds du jour. -

Nationalist Rhetoric and Public Legitimacy in Ilham Aliyev’S Azerbaijan

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository NATIONALIST RHETORIC AND PUBLIC LEGITIMACY IN ILHAM ALIYEV’S AZERBAIJAN Benjamin Midas A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of the Arts in the Global Studies department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Erica Johnson Michael Morgan Chad Bryant © 2016 Benjamin Midas ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Benjamin Midas: Nationalist Rhetoric and Public Legitimacy in Ilham Aliyev’s Azerbaijan (Under the Direction of Erica Johnson) This thesis explores the question of why nondemocratic leaders use nationalist rhetoric in ways very similar to democratic leaders through a case study of Azerbaijan. I argue that Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev uses nationalist rhetoric in order to build public legitimacy for his regime. Despite not needing to build a base of support for legitimate elections, Aliyev needs to legitimate his regime in the eyes of his citizens. To do so he uses nationalist themes in his speeches that resonate with Azerbaijani population to develop popular support. These themes come from applying theories of nationalism to the context of Azerbaijan. I will show the nationalist themes Aliyev utilizes in his speeches and how the use of those themes changes in response to events in Azerbaijan. Aliyev modulates his nationalist rhetoric in response to events in predictable ways, which shows how he manipulates nationalist themes to generate support. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………1 CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW………………………………………………………...11 CHAPTER 3: CASE STUDY……………………………………………………………………28 CHAPTER 4: CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………..47 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………......................50 iv INTRODUCTION Azerbaijan is a small country in the southern Caucasus ruled by President Ilham Aliyev. -

SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR

SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Aslan Ismayilov SUMGAYIT - BEGINNING OF THE COLLAPSE OF THE USSR 1 Aslan Ismayilov ЧАШЫОЬЛУ 2011 Aslan Ismayilov Sumgayit – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Baku Aslan Ismayilov Sumgayit – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR Baku Translated by Vagif Ismayil and Vusal Kazimli 2 SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR SUMGAYIT PROCEEDINGS 3 Aslan Ismayilov 4 SUMGAYIT – Beginning of the Collapse of the USSR HOW I WAS APPOINTED AS THE PUBLIC PROSECUTOR IN THE CASE AND OBTAINED INSIGHT OF IT Dear readers! Before I start telling you about Sumgayit events, which I firmly believe are of vital importance for Azerbaijan, and in the trial of which I represented the government, about peripeteia of this trial and other happenings which became echoes and continuation of the tragedy in Sumgayit, and finally about inferences I made about all the abovementioned as early as in 1989, I would like to give you some brief background about myself, in order to demonstrate you that I was not involved in the process occasionally and that my conclusions and position regarding the case are well grounded. Thus, after graduating from the Law Faculty of of the Kuban State University of Russia with honours, I was appointed to the Neftekumsk district court of the Stavropol region as an interne. After the lapse of some time I became the assistant for Mr Krasnoperov, the chairman of the court, who used to be the chairman of the Altay region court and was known as a good professional. The existing legislation at that time allowed two people’s assessors to participate in the court trials in the capacity of judges alongside with the actual judge. -

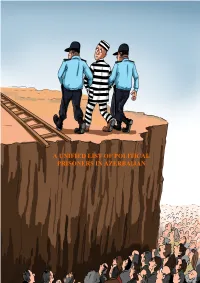

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

Interviews of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Supreme Commander-In-Chief of the Armed Forces, Mr

Interviews of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, Mr. Ilham Aliyev, to foreign media (since 27.09.2020) On November 6, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by BBC News. ........................................................................................ 3 President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by the Spanish EFE news agency. ......................................................................................19 On November 2, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by the Italian La Repubblica newspaper. .............................................25 President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev has been interviewed by German ARD TV channel. ......................................................................................29 President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev has been interviewed by Russian Interfax agency. ..........................................................................................38 On 26 October, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by the Italian Rai 1 TV channel. ..........................................................54 President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev has given an interview to the French Le Figaro newspaper. ...................................................................................57 On October 21, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev was interviewed by Japan’s -

Azerbaijan National Survey of Voters February, 2003

Azerbaijan National Survey of Voters February, 2003 Presented by, Bill Cullo Fabrizio, McLaughlin & Associates Fabrizio, McLaughlin & Associates - - Page 2 of 22 - - February, 2003 Methodology Fabrizio, McLaughlin & Associates is pleased to present the International Republican Institute (IRI) with the key findings of a survey of voter attitudes in Azerbaijan. Interviews were conducted among N=1,100 registered voters throughout the country February 15-March 5, 2003. Each interview was administered via person-to-person by a trained interviewer subcontracted through an Azeri research firm. Actual respondent selection for the study was at random using an “Nth” selection format. The number of interviews was distributed geographically using a pre-determined selection process to accurately reflect actual voter proportionality by zones throughout the country. The margin of error associated with a sample of this type is +2.9% at the 95% confidence interval. Meaning that if we conducted this same study administered in the same fashion that in 95 cases out of 100 the results would fall within +2.9% of these results. Project Objectives Most political survey projects are undertaken with multiple objectives or purposes. The Azeri project is no different in that the study was constructed to address three (3) primary objectives: 1. Gauge Political Landscape. Azerbaijan not receiving the healthy diet of surveys we do in the U.S. it was important to see how voters view their government; how voters receive the opposition parties; and where the issue matrix of voters is focused. 2. Aid the Opposition Parties. Anyone in Azerbaijan who decides to actively take part as a member of an opposition party has an extremely difficult road ahead of him. -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

Azerbaijan: Presidential Elections October 2003

AZERBAIJAN: PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS OCTOBER 2003 Report by Heidi Sødergren NORDEM Report 06/2004 Copyright: the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights/NORDEM and (author(s)). NORDEM, the Norwegian Resource Bank for Democracy and Human Rights, is a programme of the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights (NCHR), and has as its main objective to actively promote international human rights. NORDEM is jointly administered by NCHR and the Norwegian Refugee Council. NORDEM works mainly in relation to multilateral institutions. The operative mandate of the programme is realised primarily through the recruitment and deployment of qualified Norwegian personnel to international assignments, which promote democratisation and respect for human rights. The programme is responsible for the training of personnel before deployment, reporting on completed assignments, and plays a role in research related to areas of active involvement. The vast majority of assignments are channelled through the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. NORDEM Report is a series of reports documenting NORDEM activities and is published jointly by NORDEM and the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights. Series editor: Gry Kval Series consultants: Hege Mørk, Ingrid K. Ekker, Christian Boe Astrup The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher(s). ISSN: 1503–1330 ISBN: 82–90851–72-3 NORDEM Report is available online at: http://www.humanrights.uio.no/forskning/publ/publikasjonsliste.html Preface OSCE/ODIHR was invited by the Speaker of the Parliament of the Republic of Azerbaijan to observe the presidential elections that were to take place on 15 October 2003. The International Election Observation Missions (IEOM) was a joint undertaking of the OSCE’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). -

HEYDER ALIYEV CENTRE, Azerbaijan Zaha Hadid Architects Background in 2013, the Heydar Aliyev Center Opened to the Public in Baku, the Capital of Azerbaijan

HEYDER ALIYEV CENTRE, Azerbaijan Zaha Hadid Architects Background In 2013, the Heydar Aliyev Center opened to the public in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The cultural center, designed by Zaha Hadid, has become the primary building for the nation's cultural programs, aspiring instead to express the sensibilities of Azeri culture and the optimism of a nation that looks to the future. This report presents a case study of the project. It will include the background information, a synopsis of the architect's mastery of structural design. Also, some special elements of this building will be discussed in detail. And the structural design of the whole complex will be reviewed through diagrams and the simplified computer-based structural analysis. The Heydar Aliyev Center Since 1991, Azerbaijan has been working on modernizing and developing Baku’s infrastructure and architecture in order to depart from its legacy of normative Soviet Modernism. The center is named for Heydar Aliyev, the leader of Soviet-era Azerbaijan from 1969 to 1982, and President of Azerbaijan from October 1993 to October 2003. The project is located in the center of the city. And it played an extremely important role in the development of the city. It breaks from the rigid and often monumental Soviet architecture that is so prevalent in Baku. More importantly, it is a symbol of democratic philosophy thought. Under the influence of the new Azerbaijan party and the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan leader’s political and economic reform, the center was also designed to show the potential of the country’s future cultural development, to encourage people to study the history, language, culture, national creed and spiritual values of their own country.