Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Descriptive Study of Social and Economic Conditions

55 LIFE IN NAKHICHEVAN AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC: A descriptive study of social and economic conditions Supported by UNDP/ILO Ayse Kudat Senem Kudat Baris Sivri Social Assessment, LLC July 15, 2002 55 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary and Next Steps Preface Characteristics of the Region History Governance Demographics Household Demographics and Employment Conditions Employment/ Unemployment Education Economic Assessment Government Expenditures NAR’s Economic Statistics Household Expenditure Structure Income Structure Housing Conditions Determinants of Welfare Agriculture Sector in NAR Water Electricity Financing Feed for Livestock Magnitude of Land Holding Subsidies Markets NAR Region District By District Infrastructure Sector Energy Power Generation Natural Gas Project Water Supply Transportation Social Infrastructure 56 57 Health Education Enterprise Sector People’s Priorities Issues Relating to Income Generation Trust and Vision Money and Banking Community Development ARRA Damage Assessment for the Region Other Donor Activities 57 58 Summary and Next Steps The 354,000 people who live in the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic (NAR) present a unique development challenge for the Government of Azerbaijan and for the international community. Cut off and blockaded from the rest of Azerbaijan as a result of the conflict with Armenia, their traditional economic structure and markets destroyed by the collapse of the former Soviet Union, their physical and social infrastructure hampered by a decade or more of lack of maintenance and rehabilitation funding, NAR’s present status is worse than much of the rest of the country and its prospects for the future require imagination and innovative thinking. This report deals with the challenges of NAR today and what peoples’ priorities are for the future. -

Great Spotted Cuckoo Clamator Glandarius, a New Species for Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukr ainian Journal of Ecology, 2021, 11(3), 75-78, doi: 10.15421/2021_146 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Great spotted cuckoo Clamator glandarius, a new species for Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic A.F. Mammadov1*, A.V. Matsyura2, E.H. Sultanov3, A. Bayramov4 1 Institute of Bioresources of the Nakhchivan Branch of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, 10 Babek St., Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan Republic 2 Altai State University, 61 Lenin St., Barnaul, Russian Federation 3 Azerbaijan Ornithological Society, Baku Engineering University, Baku, Azerbaijan 4 Institute of Bioresources of the Nakhchivan Branch of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, 10 Babek St., Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan Republic *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Received: 10.04.2021. Accepted 22.05.2021 Clamator glandarius is reported from the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic. During the first field trip, one individual was observed, and two individuals during the second trip for species mating were registered. Keywords: Great spotted cuckoo, Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, mating, breeding season Introduction The Caucasus is one of the biodiversity hotspots, including Georgia, Azerbaijan (Nakhchivan AR), Armenia, and partly northern Iran (Fig. 1). According to Conservation International and WWF, this region is home to many endemic species and is one of the essential hotspot regions in terms of biodiversity (https://www.caucasus-naturefund.org/ecoregion/). The formation of the Caucasus goes back to the Oligocene age (33.7–23.8 Ma); while it was a small continental island in this period, it became a natural barrier by rising at the end of the Pliocene (5–2 Ma) (Demirsoy, 2008). -

History of Azerbaijan (Textbook)

DILGAM ISMAILOV HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (TEXTBOOK) Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University Methodological Council of the meeting dated July 7, 2017, was published at the direction of № 6 BAKU - 2017 Dilgam Yunis Ismailov. History of Azerbaijan, AzMİU NPM, Baku, 2017, p.p.352 Referents: Anar Jamal Iskenderov Konul Ramiq Aliyeva All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means. Electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. In Azerbaijan University of Architecture and Construction, the book “History of Azerbaijan” is written on the basis of a syllabus covering all topics of the subject. Author paid special attention to the current events when analyzing the different periods of Azerbaijan. This book can be used by other high schools that also teach “History of Azerbaijan” in English to bachelor students, master students, teachers, as well as to the independent learners of our country’s history. 2 © Dilgam Ismailov, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………….……… 9 I Theme. Introduction to the history of Azerbaijan 10 II Theme: The Primitive Society in Azerbaijan…. 18 1.The Initial Residential Dwellings……….............… 18 2.The Stone Age in Azerbaijan……………………… 19 3.The Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages in Azerbaijan… 23 4.The Collapse of the Primitive Communal System in Azerbaijan………………………………………….... 28 III Theme: The Ancient and Early States in Azer- baijan. The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms.. 30 1.The First Tribal Alliances and Initial Public Institutions in Azerbaijan……………………………. 30 2.The Kingdom of Manna…………………………… 34 3.The Atropatena and Albanian Kingdoms…………. -

REPUBLIC of AZERBAIJAN on the Right of the Manuscript

REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN On the right of the manuscript A B S T R A C T of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Science THE FAUNA AND ECOLOGY OF MINORITY TERRESTRIAL VERTEBRATES ANIMALS IN NAKHCHYVAN AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC Specialty: 2401.01 - Zoology Field of science: Biology Applicant: Arzu Farman Mammadov Baku - 2021 The dissertation work was performed in the Department of Zoological Studies of the Institute of Bioresources of the Nakhchivan Branch of the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences. Scientific supervisor: Doctor of biological sciences, prof., corresponding member of ANAS, Ilham Khayyam Alakbarov Official opponents: Doctor of biological sciences, professor Narmina Abel Sadigova Doctor of biological sciences, associate professor Giyas Nagi Guliyev Doctor of biological sciences, associate professor Namig Janali Mustafayev Doctor of biological sciences, associate professor Vafa Farman Mammadova Dissertation council BED 1.09 of Supreme Attestation Commission under the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan operating at at the Institute of Zoology of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Chairman of the Doctor of biological sciences, Dissertation council: associate professor ________ Elshad Ahmadov Scientific secretary of the PhD Biological Sciences Dissertation council: ________ Gular Aydin Huseynzade Chairman of the Doctor of biological sciences, scientific seminar: associate professor ________ Asif Abbas Manafov 2 INTRODUCTION The actuality of the subject. In modern times, the extinction of vertebrate species as a result of environmental imbalances poses a serious crisis threat. Therefore, in order to preserve the diversity of fauna, it is very important to protect their habitats and prevent the factors that affect the degradation of ecosystems. The principles of protection of vertebrate species in their natural and transformed environments make the potential for their purposeful and effective use more relevant in the future. -

Macrofungi of Nakhchivan (Azerbaijan) Autonomous Republic

Turk J Bot 36 (2012) 761-768 © TÜBİTAK Research Article doi:10.3906/bot-1101-43 Macrofungi of Nakhchivan (Azerbaijan) Autonomous Republic Hamide SEYİDOVA1, Elşad HÜSEYİN2,* 1 Institute of Bioresources, Nakhchivan Section of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan, AZ 7000, Babek st. 10, Nakhchivan - AZERBAIJAN 2 Department of Biology, Arts and Sciences Faculty, Ahi Evran University, Kırşehir - TURKEY Received: 27.01.2011 ● Accepted: 16.04.2012 Abstract: In this article, an attempt has been made to establish the species composition of the macrofungi of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic of Azerbaijan. A total of 73 species of macromycetes were registered, 2 belonging to the division Ascomycota and 71 to the division Basidiomycota. The trophic structure for the fungal species is as follows: 22 lignicolous and 51 terricolous. Fifty-three species were added to the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic mycobiota; 8 species of them were added to the mycobiota of Azerbaijan as new records. Key words: Macrofungi, new record, Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan Introduction °C in January and 41-43 °C in July-August. Relative Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (AR) is a part of humidity varies in different parts of the republic. In the Azerbaijan Republic. It is located in the south- the city of Nakhchivan it is 74%-76% in December- western part of the Lesser Caucasus Mountains. The February and 39%-40% in July-August. In the middle total length of the republic’s border is 398 km. The mountain zone it is 69%-78% and 52%-55% in region covers 5363 km2 and borders Armenia (221 December-February and July-August, respectively, km) to the east and north, Iran (179 km) to the south which is similar to the foothills of the Lesser Caucasus. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

The Outlook for Azerbaijani Gas Supplies to Europe: Challenges and Perspectives

June 2015 The Outlook for Azerbaijani Gas Supplies to Europe: Challenges and Perspectives OIES PAPER: NG 97 Gulmira Rzayeva OIES Research Associate The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2015 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-028-3 i April 2015: The Outlook for Azerbaijani Gas Supplies to Europe Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. vi Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Natural Gas in Azerbaijan – Historical Context .......................................................................... 4 The first stage of Azerbaijan’s oil and gas history (1846-1920)...................................................... -

Geopolitics and Security

978- 9941- 449- 93- 2 GEOPOLITICS AND SECURITY A NEW STRATEGY FOR THE SOUTH CAUCASUS Edited by Kornely Kakachia, Stefan Meister, Benjamin Fricke The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) is a political foundation of the Federal Republic of Germany. Democracy, peace and justice are the basic principles underlying the activities of KAS at home as well as abroad. The Foundation’s Regional Program South Caucasus conducts projects aiming at: Strengthening democratization processes, Promoting political participation of the people, Supporting social justice and sustainable economic development, Promoting peaceful conflict resolution, Supporting the region’s rapprochement with European structures. The Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) is a Tbilisi-based non-profit, in- dependent, research and analysis organization founded in early 2011. GIP strives to strengthen the organizational backbone of democratic institutions and promote good governance and development through policy research and advocacy in Georgia. It also encourages public participation in civil soci- ety-building and developing democratic processes in and outside of Georgia. The German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) is Germany’s network for foreign policy. As an independent, nonpartisan, and nonprofit membership organization, think tank, and publisher the DGAP has been promoting public debate on foreign policy in Germany for almost 60 years. The DGAP’s think tank undertakes policy-oriented research at the intersection of operational politics, business, scholarship, and the media. More -

Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned

Azerbaijan Parliamentary Elections 2005 Lessons Not Learned Human Rights Watch Briefing Paper October 31, 2005 Summary..................................................................................................................2 Background..............................................................................................................4 Past Elections ...................................................................................................... 5 Official Positions in the Lead-up to the 2005 Election Campaign ..........................6 Election Commissions .............................................................................................8 Voter Cards, IDs and Voter Lists.............................................................................8 Registration of Candidates.......................................................................................9 Media .....................................................................................................................10 Local Government Interference .............................................................................11 Candidates’ Meetings With Voters........................................................................11 Rallies ....................................................................................................................13 In the Capital, Baku........................................................................................... 13 In the Regions................................................................................................... -

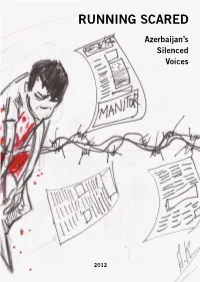

Running Scared

Running ScaRed azerbaijan’s Silenced Voices 2012 This report was compiled by: ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7324 2500 Fax: +44 20 7490 0566 E-mail: [email protected] © ARTICLE 19, London, 2012 iSBn: 978-1-906586-30-0 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 3.0 unported licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1. give credit to the International Partnership Group for Azerbaijan; 2. do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3. distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/legalcode. The International Partnership Group for Azerbaijan would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report is used. This report is published thanks to generous support from the United Kingdom Embassy in Baku. 1 List of endorsing organisations ARTICLE 19: Global Campaign for Free Expression Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road, London EC1R United Kingdom Contact: Rebecca Vincent, IPGA Project Coordinator E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +44 (0) 20 7324 2500 www.article19.org Committee to Protect Journalists 330 7th Avenue, 11th Floor New York, NY 10001 United States of America Contact: Nina Ognianova, Europe and Central Asia Program Coordinator E-mail: [email protected] Phone: +1 212 465 1004 www.cpj.org -

Statesmen and Public-Political Figures

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y CONTENTS STATESMEN, PUBLIC AND POLITICAL FIGURES ........................................................... 4 ALIYEV HEYDAR ..................................................................................................................... 4 ALIYEV ILHAM ........................................................................................................................ 6 MEHRIBAN ALIYEVA ............................................................................................................. 8 ALIYEV AZIZ ............................................................................................................................ 9 AKHUNDOV VALI ................................................................................................................. 10 ELCHIBEY ABULFAZ ............................................................................................................ 11 HUSEINGULU KHAN KADJAR ............................................................................................ 12 IBRAHIM-KHALIL KHAN ..................................................................................................... 13 KHOYSKI FATALI KHAN ..................................................................................................... 14 KHIABANI MOHAMMAD ..................................................................................................... 15 MEHDİYEV RAMİZ ............................................................................................................... -

AZERBAIJAN's DARK ISLAND: Human Rights Violations In

2009 • 2 REPORT AZERBAIJAN’S DARK ISLAND: Human rights violations in Nakhchivan Contents A. Summary .........................................................................................................5 B. Nakhchivan: Background and Political System ................................................8 1. A family affair ............................................................................................12 2. The economic role of the Family ................................................................14 3. The Nakhchivan clan: A driving force in Azerbaijani politics .....................15 C. Violations of basic rights in Nakhchicvan .....................................................20 1. The Media .................................................................................................25 2. Police brutality: An instrument to silence critics .........................................33 3. The practice of torture ...............................................................................37 4. Psychiatric Hospitals: “Curing” opponents .................................................38 5. Politically motivated dismissals ..................................................................42 D. The regime’s peculiar tools ...........................................................................45 1. Forced weekend work in the fields ............................................................45 Map of Azerbaijan with Nakhchivan. www.joshuakucera.net 2. Weird and unwritten laws ..........................................................................46