The Infl Constituent in the Mundani Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

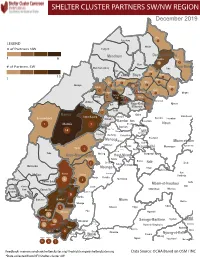

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Paix

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix - Travail - Patrie Peace - Work - Fatherland MINISTRY OF MINES, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2017 OF THE MINES, INDUSTRY AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT SUBSECTOR FOREWORD The Ministry of Mines, Industry and Technological Development is pleased to present the statistical yearbook of the Mines, Industry and Technological Development sub-sector, MIDTSTAT, 2017edition. Its aim is to put at the disposal of actors of the sub-sector on the one hand, and of the general public, on the other hand, statistical data which illustrate the actions and development policies implemented in this ministerial department. The document presents a series of statistical information relating, on the one hand, to contextual data on Cameroon and, on the other hand, to the mines, industry and technological development components. I, therefore, invite all potential users of the information contained in this valuable document to make good use of it, and to generate actions likely to further improve the performance of our sub-sector. I would like to seize this opportunity to express my appreciation to all those who have, in one way or another, contributed towards elaborating this document, in particular the National Institute of Statistics for its support, the central and devolved services of MINMIDT, structures under its supervisory authority, as well as the administrations called upon to provide statistical information. We welcome suggestions and contributions likely to enrich and improve -

Case Studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria)

Open Linguistics 2021; 7: 244–300 Research Article Bruce Connell*, David Zeitlyn, Sascha Griffiths, Laura Hayward, and Marieke Martin Language ecology, language endangerment, and relict languages: Case studies from Adamawa (Cameroon-Nigeria) https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2021-0011 received May 18, 2020; accepted April 09, 2021 Abstract: As a contribution to the more general discussion on causes of language endangerment and death, we describe the language ecologies of four related languages (Bà Mambila [mzk]/[mcu], Sombә (Somyev or Kila)[kgt], Oumyari Wawa [www], Njanga (Kwanja)[knp]) of the Cameroon-Nigeria borderland to reach an understanding of the factors and circumstances that have brought two of these languages, Sombә and Njanga, to the brink of extinction; a third, Oumyari, is unstable/eroded, while Bà Mambila is stable. Other related languages of the area, also endangered and in one case extinct, fit into our discussion, though with less focus. We argue that an understanding of the language ecology of a region (or of a given language) leads to an understanding of the vitality of a language. Language ecology seen as a multilayered phenom- enon can help explain why the four languages of our case studies have different degrees of vitality. This has implications for how language change is conceptualised: we see multilingualism and change (sometimes including extinction) as normative. Keywords: Mambiloid languages, linguistic evolution, language shift 1 Introduction A commonly cited cause of language endangerment across the globe is the dominance of a colonial language. The situation in Africa is often claimed to be different, with the threat being more from national or regional languages that are themselves African languages, rather than from colonial languages (Batibo 2001: 311–2, 2005; Brenzinger et al. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5 -

Hydropower in Cameroon

Hydropower in Cameroon DEPARTMENT OF BUILDING, ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ENGINEERING Hydropower in Cameroon Sebastien Tchuidjang Tchouaha Bachelors Thesis in Energy System Engineering Examiner: Ulf Larsson Supervisor: Ulf Larsson Page | 1 Hydropower in Cameroon Page | 2 Hydropower in Cameroon Acknowledgment Firstly, this thesis topic Hydropower in Cameroon has finally come to an end after some months of hard work, studies and research from different articles and books. Secondly, am thankful for having the opportunity to write on this topic with the help and approval of my head of department Ulf Larsson who has being of grate help and support throughout these past months. Furthermore, I will like to thank Belinda Fonyam my Fiancé, Yvonne a friend and some of my family members back home (Cameroon) for their assistance and support during this past months. Finally, I admit with gratitude the contribution of the scholars, journals, presses, the publishers of the article Global Village Cameroon (GVC), Mr. Kum Julius, Mr. Jie Cai, Mr. Egbe Tah Franklin, the ministry of Water and Energy (MINEE) and my brother Mr. Ndontsi Marcel a teacher in Cameroon whom has been instrumental during my research. Page | 3 Hydropower in Cameroon Page | 4 Hydropower in Cameroon Abstract Now our days with the great development of science and technology, it‟s of more importance to develop renewable energy sources used for electricity generation. I wish to introduce something about the Cameroonian water resources. Hydropower being one of the most used source of energy production in the world it has also developed rapidly in Cameroon whereby about 90% of the electricity generated is from hydropower and it also help in bursting the country‟s economy by exportation to neighbouring countries. -

The State of Cameroon's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture

COUNTRY REPORTS THE STATE OF CAMEROON’S BIODIVERSITY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE This country report has been prepared by the national authorities as a contribution to the FAO publication, The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. The report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the content of this document is entirely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the views of FAO, or its Members. The designations employed and the presentation of material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. MINISTRY OFAGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (MINADER) THE STATE OF BIODIVERSITY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE IN CAMEROON November 2015 MINISTRY OFAGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT (MINADER) THE STATE OF BIODIVERSITY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE IN CAMEROON November 2015 i CITATION This document will be cited as: MINADER (2015). The State of Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture in the Republic of Cameroon. -

The Last Great Ape Organization, Cameroon Laga

THE LAST GREAT APE ORGANIZATION, CAMEROON LAGA ANNUAL REPORT JANUARY – DECEMBER 2014 Executive Summary Despite many obstacles, tangible achievements were made over this period in LAGA’s collaboration with MINFOF in the fields of investigation, arrest, prosecution, media exposure, government relations and international activities. Focus was on the fight against corruption, the illegal wildlife trade especially the specialized illicit trade in ape parts including fresh chimpanzee and gorilla heads, limbs and skulls; ivory and elephant products trafficking and the illicit trade in giant pangolin scales and leopards skins . The wildlife law enforcement operations carried out this year also busted international connections in ivory trafficking, ape parts and giant pangolin scales. This year, LAGA focused on the illegal trade in ape skulls uncovering an unprecedented magnitude of this specialized trade with 77 ape skulls seized and 25 traffickers arrested. 86% of those arrested stayed permanently behind bars from the moment of arrest and during the trial process while 10% were granted bail along the line and 4% were released and never prosecuted. Corruption was observed and fought in more than 80% of the cases. Operations focused on the illicit trade in ape parts and the trafficking in elephant bones and ivory while demonstrating the link between the two. 50 new cases were brought to court, 18 traffickers convicted and more than $326,000 to be paid as damages. Media exposure was at a rate of more than one media piece per day. Replication was concretized in Senegal - EAGLE replication, with SALF starting operations and AALF-B was launched in Benin with good operations. -

Programmation De La Passation Et De L'exécution Des Marchés Publics

PROGRAMMATION DE LA PASSATION ET DE L’EXÉCUTION DES MARCHÉS PUBLICS EXERCICE 2021 JOURNAUX DE PROGRAMMATION DES MARCHÉS DES SERVICES DÉCONCENTRÉS ET DES COLLECTIVITÉS TERRITORIALES DÉCENTRALISÉES RÉGION DE L’OUEST EXERCICE 2021 SYNTHESE DES DONNEES SUR LA BASE DES INFORMATIONS RECUEILLIES Nbre de Montant des N° Désignation des MO/MOD N° Page Marchés Marchés 1 Services déconcentrés régionaux 14 526 746 000 3 2 Communauté Urbaine de Bafoussam 18 9 930 282 169 5 Département des Bamboutos 3 Services déconcentrés 6 177 000 000 7 4 Commune de Babadjou 12 350 710 000 7 5 Commune de Batcham 8 250 050 004 9 6 Commune de Galim 6 240 050 000 10 7 Commune de Mbouda 25 919 600 000 10 TOTAL 57 1 937 410 004 Département du Haut Nkam 8 Services Déconcentrés 4 81 000 000 13 9 Commune de Bafang 7 236 000 000 13 10 Commune de Bakou 11 146 250 000 14 11 Commune de Bana 6 172 592 696 15 12 Commune de Bandja 14 294 370 000 16 13 Commune de Banka 14 409 710 012 17 14 Commune de Banwa 10 155 249 999 19 15 Commune de Kékem 5 152 069 520 20 TOTAL 71 1 647 242 227 Département des Hauts Plateaux 16 Services déconcentrés départementaux 1 10 000 000 21 17 Commune de Baham 11 195 550 000 21 18 Commune de Bamendjou 12 367 102 880 22 19 Commune de Bangou 20 371 710 000 24 20 Commune de Batié 6 146 050 002 26 TOTAL 50 1 090 412 882 Département du Koung Khi 21 Services Déconcentrés 2 122 000 000 27 22 Commune de Bayangam 6 257 710 000 27 23 Commune de Dembeng 5 180 157 780 28 24 Commune de Pete Bandjoun 12 287 365 000 28 TOTAL 25 847 232 780 Département de la Menoua 25 -

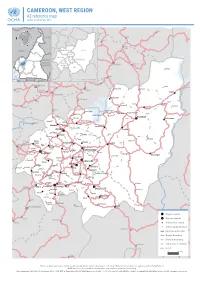

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 Reference Map Update of September 2018

CAMEROON, WEST REGION A3 reference map Update of September 2018 Nwa Ndu Benakuma CHAD WUM Nkor Tatum NIGERIA BAMBOUTOS NOUN FUNDONGMIFI MENOUA Elak NKOUNG-KHI CENTRAL H.-P. Njinikom AFRICAN HAUT- KUMBO Mbiame REPUBLIC -NKAM Belo NDÉ Manda Njikwa EQ. Bafut Jakiri GUINEA H.-P. : HAUTS--PLATEAUX GABON CONGO MBENGWI Babessi Nkwen Koula Koutoukpi Mabouo NDOP Andek Mankon Magba BAMENDA Bangourain Balikumbat Bali Foyet Manki II Bangambi Mahoua Batibo Santa Njimom Menfoung Koumengba Koupa Matapit Bamenyam Kouhouat Ngon Njitapon Kourom Kombou FOUMBAN Mévobo Malantouen Balepo Bamendjing Wabane Bagam Babadjou Galim Bati Bafemgha Kouoptamo Bamesso MBOUDA Koutaba Nzindong Batcham Banefo Bangang Bapi Matoufa Alou Fongo- Mancha Baleng -Tongo Bamougoum Foumbot FONTEM Bafou Nkong- Fongo- -Zem -Ndeng Penka- Bansoa BAFOUSSAM -Michel DSCHANG Momo Fotetsa Malânden Tessé Fossang Massangam Batchoum Bamendjou Fondonéra Fokoué BANDJOUN BAHAM Fombap Fomopéa Demdeng Singam Ngwatta Mokot Batié Bayangam Santchou Balé Fondanti Bandja Bangang Fokam Bamengui Mboébo Bangou Ndounko Baboate Balambo Balembo Banka Bamena Maloung Bana Melong Kekem Bapoungué BAFANG BANGANGTÉ Bankondji Batcha Mayakoue Banwa Bakou Bakong Fondjanti Bassamba Komako Koba Bazou Baré Boutcha- Fopwanga Bandounga -Fongam Magna NKONGSAMBA Ndobian Tonga Deuk Region capital Ebone Division capital Nkondjock Manjo Subdivision capital Other populated place Ndikiniméki InternationalBAF borderIA Region boundary DivisionKiiki boundary Nitoukou Subdivision boundary Road Ombessa Bokito Yingui The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. NOTE: In places, the subdivision boundaries may suffer of significant inacurracy. Date of update: 23/09/2018 ● Sources: NGA, OSM, WFP ● Projection: WGS84 Web Mercator ● Scale: 1 / 650 000 (on A3) ● Availlable online on www.humanitarianresponse.info ● www.ocha.un.org. -

Child Marriage in Rural Cameroon: the Case of Magba in the West Region

Child Marriage in Rural Cameroon: The Case of Magba in the West Region Achu Frida Njiei Researcher/ Anthropologist National Centre For Education Ministry Of Scientific Research And Innovation P. O Box 1721 Yaounde , Cameroon Norah Aziamin Asongu Researcher/ Anthropologist National Centre For Education Ministry Of Scientific Research And Innovation P. O Box 1721 Yaounde , Cameroon ABSTRACT In spite of the long term struggle for the empowerment of women by international bodies, governments and non-governmental organisations, which has greatly improved the situation of women in Cameroon, certain cultural practices still relegate woman to the background. Child marriage is one of these cultural practices that do not only deprive a woman of her legal rights, but also of her social and economic opportunities. Marriage of girls below 15 years of age is still very common in Magba like in other rural communities in Cameroon. The pertinence of this topic is seen where ironically, men are not the only people who promote this practice but mothers of these girls are equally perpetrators of this act. Due to the high illiteracy rates of women in the Magba community, they are ignorant of the consequences of early marriage. In addition, the culture of the people, championed by men who are custodians of the tradition, believe that if at 20 years a girl is not married, there are very few chances of her getting married since men fear that she could be barren, not attractive or has a bad family history. This belief has encouraged most young girls to be interested in early marriage for fear of stigmatization by the community. -

Forecasts and Dekadal Climate Alerts for the Period 11Th to 20Th August 2021

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ----------- ----------- OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR NATIONAL OBSERVATORY LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES ON CLIMATE CHANGE ----------------- ----------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECTORATE GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- ONACC www.onacc.cm; [email protected]; Tel : (+237) 693 370 504 / 654 392 529 BULLETIN N° 89 Forecasts and Dekadal Climate Alerts for the Period 11th to 20th August 2021 th 11 August 2021 © NOCC August 2021, all rights reserved Supervision Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). Production Team (NOCC) Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, PhD student and Technical staff, NOCC. ZOUH TEM Isabella, M.Sc. in GIS-Environment and Technical staff, NOCC. NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. MEYONG Rene Ramses, M.Sc. in Physical Geography (Climatology/Biogeography). ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, NOCC. MEKA ZE Philemon Raïssa, Administrative staff, NOCC. ELONG Julien -

Democratisation and Political Participation of Mbororo in Western Cameroon Ibrahim Mouiche

● ● ● ● Africa Spectrum 2/2011: 71-97 Democratisation and Political Participation of Mbororo in Western Cameroon Ibrahim Mouiche Abstract: Over the last two decades, the Mbororo – a “marginal” ethnic group – have experienced some unexpected rewards due to a new policy in Cameroon’s West Region. Among the changes that affected the Mbororo were the following: a new legal-institutional framework (the 1996 Constitu- tion), the consequences of the multi-party competition since 1990, and the mobilisation outside of political parties in the framework of an association for the promotion of ethnic interests (the MBOSCUDA, founded 1992). The combination of these factors has led to a Mbororo political awakening. This contribution aims to better understand the determinants and key play- ers in this development. Manuscript received 4 July 2011; accepted 28 November 2011 Keywords: Cameroon, democratisation, political participation, minority groups, Mbororo Ibrahim Mouiche is a political scientist specialising in Political Sociology and Political Anthropology. He earned his doctoral degrees at Yaoundé Uni- versity (1994) and Leiden University (2005), and he is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Yaoundé II. His research interests include ethnicity and ethnic minorities; traditional chiefs and democratization; gender; and Islam and reformism in Cameroon. He is currently a fellow at the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities and Social Sciences. 72 Ibrahim Mouiche Over the past two decades, the Mbororo, a “marginal” ethnic group, ac- cording to the official terminology,1 experienced unexpected recognition due to political factors in the West Region of Cameroon. The causes and consequences of this profound change are largely unknown.