Eli, the Fanatic"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Half Fanatics August 2014 Newsletter

HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Angela #8730 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Race Photos ...…………….. 1 Featured Fanatic…………... 2 Expo Schedule………………3 Fanatic Poll…………………..3 Sporty Diva Half Marathon Upcoming Races…………… 5 HF Membership Criteria…... 7 Jamila #3959, Loan #4026, Alicia, and BustA Groove #3935 Half Fanatic Pace Team…. ..7 Meghan #7202 New HF Gear……………….. .8 New Moons………………….. 8 Welcome to the Asylum…... 9 Shaun #7485 & Cathy #1756 Meliessa #8722 1 http://www.halffanatics.com 1 HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Featured Fanatic Yvette Todd, Half Fanatic #5517 “50 in 50” and Embracing the Sun The idea of my challenge was borne in June 2011. I met a fellow camper/runner at the Colworth Marathon Challenge running event - 3 races, 3 days, 26.2 miles. The runner was extremely pleased to be there as he was able to bag 3 races in one weekend for what he called his “50 in 50 challenge” - 50 running events in his 50th year. Inspired, I decided to cele- brate this landmark age by doing 50 half marathons as a 50 year old - my own version of the “50 in 50” and planned to start the challenge right after I ran a mara- thon on my 50th birthday! Two challenges? Well the last one, I have been dreaming about for a few years, in fact, ever since I did the New York Marathon back in 2006 where I met a fellow lady runner staying in the same hotel as me. She was ecstatic the whole weekend as she was running the New York marathon on her actual 50th birthday. -

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’S Sorority Life

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’s Sorority Life Kyle Dunst Writer’s comment: I originally wrote this piece for an American Studies seminar. The class was about consumption, and it focused on how Americans define themselves through the products they purchase. My professor, Carolyn de la Pena, really encouraged me to pursue my interest in advertising. If it were not for her, UC Davis would have very little in regards to studying marketing. —Kyle Dunst Instructor’s comment:Kyle wrote this paper for my American Studies senior seminar on consumer culture. I encouraged him to combine his interests in marketing with his personal fearlessness in order to put together a somewhat covert final project: to infiltrate the UC Davis- based Sorority Life reality show and discover the role that consumer objects played in creating its “reality.” His findings help us de-code the role of product placement in the genre by revealing the dual nature of branded objects on reality shows. On the one hand, they offset costs through advertising revenues. On the other, they create a materially based drama within the show that ensures conflict and piques viewer interest. The ideas and legwork here were all Kyle; the motivational speeches and background reading were mine. —Carolyn de la Pena, American Studies PRIZED WRITING - 61 KYLE DUNST HAT DO THE OSBOURNES, Road Rules, WWF Making It!, Jack Ass, Cribs, and 12 seasons of Real World have in common? They Ware all examples of reality-MTV. This study analyzes prod- uct placement and advertising in an MTV reality show familiar to many of the students at the University of California, Davis, Sorority Life. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Sammy Figueroa Full

Sammy Figueroa has long been regarded as one of the world’s great musicians. As a much-admired percussionist he provided the rhythmical framework for hundreds of hits and countless recordings. Well-known for his versatility and professionalism, he is equally comfortable in a multitude of styles, from R & B to rock to pop to electronic to bebop to Latin to Brazilian to New Age. But Sammy is much more than a mere accompanist: when Sammy plays percussion he tells a story, taking the listener on a journey, and amazing audiences with both his flamboyant technique and his subtle nuance and phrasing. Sammy Figueroa is now considered to be the most likely candidate to inherit the mantles of Mongo Santamaria and Ray Barretto as one of the world’s great congueros. Sammy Figueroa was born in the Bronx, New York, the son of the well-known romantic singer Charlie Figueroa. His first professional experience came at the age of 18, while attending the University of Puerto Rico, with the band of bassist Bobby Valentin. During this time he co-founded the innovative Brazilian/Latin group Raices, which broke ground for many of today’s fusion bands. Raices was signed to a contract with Atlantic Records and Sammy returned to New York, where he was discovered by the great flautist Herbie Mann. Sammy immediately became one of the music world’s hottest players and within a year he had appeared with John McLaughlin, the Brecker Brothers and many of the world’s most famous pop artists. Since then, in a career spanning over thirty years, Sammy has played with a -

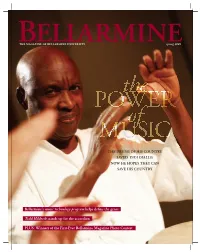

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

2016 School Library Partner Manual

2016 School Library Partner Manual School Library Partner Manual Contents Summer Reading at New York Libraries: An Introduction .................. 3 2016 Summer Reading ....................................................................... 4 Summer Reading and Your School Library ......................................... 5 Collaborate with your local public library!.........................................................5 Promote summer reading at your school by working with faculty, students, and families ...............................................................................................................6 Summer Reading Websites, Resources, Information, and Materials ... 7 General Summer Reading Resources ................................................. 8 Information and Research ...................................................................................8 Promotional Materials .........................................................................................8 Educators Flyer ...............................................................................................9 Parents Flyer (Side 1) .................................................................................... 10 Parents Flyer (Side 2) .................................................................................... 11 Parents of Young Children Flyer ................................................................... 12 Teen Video Challenge Flyer ......................................................................... 13 Teen NY Flyer -

“My Son the Fanatic” by Hanif Kureishi

video tapes, new books and fashionableW clothes the boy had bought just a few months before. Also without explanation, Ali had parted from the English girlfriend who used to come often to the house. His old friends had stopped ringing. For reasons he didn't himself understand, Parvez wasn't able to bring up the subject of Ali's unusual behaviour. He was aware that he had become slightly afraid of his son, who, between his silences, was developing a sharp tongue. One remark Pawez did make, 'You don't play your guitar any more,' elicited the mysterious but conclu- sive reply, 'There are more important things to be done.' Yet Parvez felt his son's eccentricity an injustice. He had al- ways been aware of the pitfalls that other men's sons had fallen into in England. And so, for Ali, he had worked long hours and spent a lot of money paying for his education as an accountant. He had bought him good suits, all the books he required and a computer. And now the boy was throwing his possessions out! - - The TV, video and sound system followed the guitar. Soon the room was practically bare. Even the unhappy walls bore marks where Ali's pictures had been removed. Parvez couldn't sleep; he went more to the whisky bottle, even when he was at work. He realised it was imperative to discuss the matter with someone sympathetic. HANIF KUREISHI My Son the Fanatic Surreptitiously, the father began going into his son's bedroom. He would sit there for hours, rousing himself only to seek clues. -

Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson a Dissertation S

Mothers in the Family of Saints: Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paul Christopher Johnson, Chair Associate Professor Paulina Alberto Associate Professor Victoria Langland Associate Professor Gayle Rubin Jamie Lee Andreson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1305-1256 © Jamie Lee Andreson 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the women of Candomblé, and to each person who facilitated my experiences in the terreiros. ii Acknowledgements Without a doubt, the most important people for the creation of this work are the women of Candomblé who have kept traditions alive in their communities for centuries. To them, I ask permission from my own lugar de fala (the place from which I speak). I am immensely grateful to every person who accepted me into religious spaces and homes, treated me with respect, offered me delicious food, good conversation, new ways of thinking and solidarity. My time at the Bate Folha Temple was particularly impactful as I became involved with the production of the documentary for their centennial celebrations in 2016. At the Bate Folha Temple I thank Dona Olga Conceição Cruz, the oldest living member of the family, Cícero Rodrigues Franco Lima, the current head priest, and my closest friend and colleague at the temple, Carla Nogueira. I am grateful to the Agência Experimental of FACOM (Department of Communications) at UFBA (the Federal University of Bahia), led by Professor Severino Beto, for including me in the documentary process. -

Tension Between Reform and Orthodox Judaism in “Eli, the Fanatic”

Undergraduate Review Volume 13 Article 14 2017 Tension between Reform and Orthodox Judaism in “Eli, The aF natic” Katie Grant Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Grant, Katie (2017). Tension between Reform and Orthodox Judaism in “Eli, The aF natic”. Undergraduate Review, 13, 106-116. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol13/iss1/14 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2017 Katie Grant have caused interdenominational tension throughout Tension Between history, but “Eli, The Fanatic” captures the specific struggles of the post-Holocaust era. The story presents Reform and devastating insight into the obstacles that Orthodox Jews from Germany faced upon immigrating to Ameri- Orthodox Judaism ca to escape persecution in the 1930s and 1940s, as well in “Eli, the Fanatic” as the struggles that Reform sects faced upon accepting the exiles into their communities. The story exemplifies the challenges that Orthodox and Reform sects endure KATIE GRANT when they live in close proximity, and the social and political forces that can prevent the sects from living together amicably. he relationship between fundamentalist Jewish The story is set in the fictional town of Wood- sects and progressive Jewish sects is constant- enton, New York, which is portrayed as a sheltered and Tly evolving and is greatly -

Brands, Markets and Charitable Ethics: MTV's EXIT Campaign

Brands, Markets and Charitable Ethics: MTV’s EXIT Campaign Jane Arthurs Abstract: This case study of MTV‟s EXIT campaign to raise awareness about the trafficking of women highlights the difficulties faced by charitable organisations when using audience research to evaluate the effectiveness of their media campaigns. If they were to follow the advice to connect with audiences whose ethical and political commitments have been shaped within a media saturated, capitalist culture, they risk reinforcing the positioning of women‟s bodies as consumable products in a pleasure-oriented service economy and further normalisation of the practices the campaigners are seeking to prevent. To be effective in the longer term charities require an ethical approach to media campaigns that recognises their political dimension and the shift in values required. The short term emotional impact on audiences needs to be weighed against these larger ethical and political considerations to avoid the resulting films becoming too individualistic and parochial, a mirror image of their audience‟s „unreconstructed‟ selves. Key Words: Human trafficking, sexual exploitation, media charity campaigns, film, ethics, aesthetics, consumerism, empathy, authenticity, cosmopolitanism Introduction This article examines the ethical implications of the aesthetic decisions that charities make when they commission films for their campaigns against human trafficking and the role that audience research can play in informing those decisions. There has been a large growth in the media attention given to this issue since the late 1990s. The use of short films in campaigns to raise public awareness has also increased during this period as new distribution outlets have become available with firstly DVD extras and then video downloads on the web making it much easier to find an audience outside the more restrictive advertising slots on television. -

Dancers to Deliver Workshops to Experience This Remarkable Work at a to Grow

ORB Sydney Sydney Dance Dance Company Company 2 One Another Proudly taking 2 ONE ANOTHER to Shanghai later this month www.samsonite.com.au/red Sydney Dance Company New Breed 30 Nov – 9 Dec Carriageworks All tickets $35 BOOK NOW At the box office or via roslynpackertheatre.com.au carriageworks.com.au Made possible by: Welcome Message 2—3 Sydney Dance Company is pleased to welcome Reaching out to and engaging young people you to 2 One Another - a full length work by is integral to everything we do, and in 2017, Rafael Bonachela. Since it was created in 2012, our education and public programs continue 2 One Another has had an extraordinary touring to grow. Over the winter months, our teaching life, both in Australia and internationally. It artists have travelled extensively alongside seemed only right that we should celebrate its the Company dancers to deliver workshops 100th performance by bringing it back to the in schools throughout regional Australia, stage it premiered on. in parallel with our national tour across six states and territories. During this 2 This work has been warmly received by One Another season, a whole new group of audiences all over the world and we are secondary students will have the chance #SDC2OneAnother delighted that after this Sydney season, it to experience this remarkable work at a will have its Chinese premiere as part of the school matinee. 2017 Shanghai International Arts Festival. 2 One Another will be performed in Zhongshan Everything that Sydney Dance Company (The People’s) Park before the Company achieves and delivers around the country and takes to the stage of the Shanghai Grand across the world is made possible through the Theatre to present a double bill of Cacti support of our philanthropic and corporate and Lux Tenebris. -

TRANSCRIPT by FLYING FANATIC EFA Episode 15

TRANSCRIPT BY FLYING FANATIC EFA Episode 15 - Too Cool for School [ph] – Indicates preceding word has been spelled phonetically [sic] – Indicates preceding word has been transcribed verbatim MUSIC : Write My Story by Olly Anna ANNOUNCER GUY : You've tuned in to the Earp Fiction Addiction , a fan podcast all about Wynonna Earp fanfiction. Join our intrepid host DarkWiccan and Delayne as they dive deep into the sometimes sweet, sometimes spicy, and always varied world of fanfiction for the Wynonna Earp fandom. MUSIC : A Proper Story by Darren Korb DARKWICCAN : Thanks Announcer Guy and welcome everybody to the Earp Fiction Addiction , the podcast dedicated entirely to Wynonna Earp fanfiction, I am your host DarkWiccan and with me is my co-host - DELAYNE : Hi, it’s Delayne! DARKWICCAN : And this week we’re getting all sorts of nostalgic for the nineties. Not because the stories are set in the nineties, but because that’s when Delayne and I were in high school. [laughter] Because this week we are dedicating the episode to our favorite High School AUs. DELAYNE : I know it’s called “Too cool for school”, but I was definitely “too school for cool”. [laughter] I will put that one out there for here. DARKWICCAN : [laughter] Well, y'know, I think that’s true for more folks than not, you know what I mean? Like, yeah there were those, of course, the stereotypical jocks, and preps, and whatnot, but I think most folks I talk to they were like, “No, I wasn’t the popular one, I was a pretty studious person”, and the thing is, is I hear that so often it feels like most people thought they weren’t the popular one, and most people thought they were pretty studious.