Video Artists As Citizen Scientists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Half Fanatics August 2014 Newsletter

HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Angela #8730 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Race Photos ...…………….. 1 Featured Fanatic…………... 2 Expo Schedule………………3 Fanatic Poll…………………..3 Sporty Diva Half Marathon Upcoming Races…………… 5 HF Membership Criteria…... 7 Jamila #3959, Loan #4026, Alicia, and BustA Groove #3935 Half Fanatic Pace Team…. ..7 Meghan #7202 New HF Gear……………….. .8 New Moons………………….. 8 Welcome to the Asylum…... 9 Shaun #7485 & Cathy #1756 Meliessa #8722 1 http://www.halffanatics.com 1 HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Featured Fanatic Yvette Todd, Half Fanatic #5517 “50 in 50” and Embracing the Sun The idea of my challenge was borne in June 2011. I met a fellow camper/runner at the Colworth Marathon Challenge running event - 3 races, 3 days, 26.2 miles. The runner was extremely pleased to be there as he was able to bag 3 races in one weekend for what he called his “50 in 50 challenge” - 50 running events in his 50th year. Inspired, I decided to cele- brate this landmark age by doing 50 half marathons as a 50 year old - my own version of the “50 in 50” and planned to start the challenge right after I ran a mara- thon on my 50th birthday! Two challenges? Well the last one, I have been dreaming about for a few years, in fact, ever since I did the New York Marathon back in 2006 where I met a fellow lady runner staying in the same hotel as me. She was ecstatic the whole weekend as she was running the New York marathon on her actual 50th birthday. -

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’S Sorority Life

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’s Sorority Life Kyle Dunst Writer’s comment: I originally wrote this piece for an American Studies seminar. The class was about consumption, and it focused on how Americans define themselves through the products they purchase. My professor, Carolyn de la Pena, really encouraged me to pursue my interest in advertising. If it were not for her, UC Davis would have very little in regards to studying marketing. —Kyle Dunst Instructor’s comment:Kyle wrote this paper for my American Studies senior seminar on consumer culture. I encouraged him to combine his interests in marketing with his personal fearlessness in order to put together a somewhat covert final project: to infiltrate the UC Davis- based Sorority Life reality show and discover the role that consumer objects played in creating its “reality.” His findings help us de-code the role of product placement in the genre by revealing the dual nature of branded objects on reality shows. On the one hand, they offset costs through advertising revenues. On the other, they create a materially based drama within the show that ensures conflict and piques viewer interest. The ideas and legwork here were all Kyle; the motivational speeches and background reading were mine. —Carolyn de la Pena, American Studies PRIZED WRITING - 61 KYLE DUNST HAT DO THE OSBOURNES, Road Rules, WWF Making It!, Jack Ass, Cribs, and 12 seasons of Real World have in common? They Ware all examples of reality-MTV. This study analyzes prod- uct placement and advertising in an MTV reality show familiar to many of the students at the University of California, Davis, Sorority Life. -

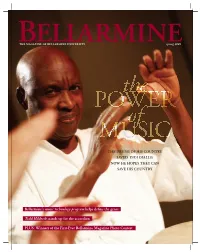

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

“My Son the Fanatic” by Hanif Kureishi

video tapes, new books and fashionableW clothes the boy had bought just a few months before. Also without explanation, Ali had parted from the English girlfriend who used to come often to the house. His old friends had stopped ringing. For reasons he didn't himself understand, Parvez wasn't able to bring up the subject of Ali's unusual behaviour. He was aware that he had become slightly afraid of his son, who, between his silences, was developing a sharp tongue. One remark Pawez did make, 'You don't play your guitar any more,' elicited the mysterious but conclu- sive reply, 'There are more important things to be done.' Yet Parvez felt his son's eccentricity an injustice. He had al- ways been aware of the pitfalls that other men's sons had fallen into in England. And so, for Ali, he had worked long hours and spent a lot of money paying for his education as an accountant. He had bought him good suits, all the books he required and a computer. And now the boy was throwing his possessions out! - - The TV, video and sound system followed the guitar. Soon the room was practically bare. Even the unhappy walls bore marks where Ali's pictures had been removed. Parvez couldn't sleep; he went more to the whisky bottle, even when he was at work. He realised it was imperative to discuss the matter with someone sympathetic. HANIF KUREISHI My Son the Fanatic Surreptitiously, the father began going into his son's bedroom. He would sit there for hours, rousing himself only to seek clues. -

Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson a Dissertation S

Mothers in the Family of Saints: Gender and Race in the Making of Afro-Brazilian Heritage by Jamie Lee Andreson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Paul Christopher Johnson, Chair Associate Professor Paulina Alberto Associate Professor Victoria Langland Associate Professor Gayle Rubin Jamie Lee Andreson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1305-1256 © Jamie Lee Andreson 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all the women of Candomblé, and to each person who facilitated my experiences in the terreiros. ii Acknowledgements Without a doubt, the most important people for the creation of this work are the women of Candomblé who have kept traditions alive in their communities for centuries. To them, I ask permission from my own lugar de fala (the place from which I speak). I am immensely grateful to every person who accepted me into religious spaces and homes, treated me with respect, offered me delicious food, good conversation, new ways of thinking and solidarity. My time at the Bate Folha Temple was particularly impactful as I became involved with the production of the documentary for their centennial celebrations in 2016. At the Bate Folha Temple I thank Dona Olga Conceição Cruz, the oldest living member of the family, Cícero Rodrigues Franco Lima, the current head priest, and my closest friend and colleague at the temple, Carla Nogueira. I am grateful to the Agência Experimental of FACOM (Department of Communications) at UFBA (the Federal University of Bahia), led by Professor Severino Beto, for including me in the documentary process. -

Brands, Markets and Charitable Ethics: MTV's EXIT Campaign

Brands, Markets and Charitable Ethics: MTV’s EXIT Campaign Jane Arthurs Abstract: This case study of MTV‟s EXIT campaign to raise awareness about the trafficking of women highlights the difficulties faced by charitable organisations when using audience research to evaluate the effectiveness of their media campaigns. If they were to follow the advice to connect with audiences whose ethical and political commitments have been shaped within a media saturated, capitalist culture, they risk reinforcing the positioning of women‟s bodies as consumable products in a pleasure-oriented service economy and further normalisation of the practices the campaigners are seeking to prevent. To be effective in the longer term charities require an ethical approach to media campaigns that recognises their political dimension and the shift in values required. The short term emotional impact on audiences needs to be weighed against these larger ethical and political considerations to avoid the resulting films becoming too individualistic and parochial, a mirror image of their audience‟s „unreconstructed‟ selves. Key Words: Human trafficking, sexual exploitation, media charity campaigns, film, ethics, aesthetics, consumerism, empathy, authenticity, cosmopolitanism Introduction This article examines the ethical implications of the aesthetic decisions that charities make when they commission films for their campaigns against human trafficking and the role that audience research can play in informing those decisions. There has been a large growth in the media attention given to this issue since the late 1990s. The use of short films in campaigns to raise public awareness has also increased during this period as new distribution outlets have become available with firstly DVD extras and then video downloads on the web making it much easier to find an audience outside the more restrictive advertising slots on television. -

From Calypsos to Careers: Post Dance Life of the Texas

FROM CALYPSOS TO CAREERS: POST DANCE LIFE OF THE TEXAS STATE UNIVERSITY STRUTTERS ALUMNAE by Anne Marie Callahan, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Sociology May 2019 Committee Members: Joseph A. Kotarba, Chair Bob Price Susan Morrison COPYRIGHT by Anne Marie Callahan 2019 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Anne Marie Callahan, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION To my loving and patient family, Mom, Dad, and RJ. I could not have done this without you. I will be forever grateful for everything you have done for me. Love, Murry. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my wonderful professors, Dr. Joseph A. Kotarba, Dr. Bob Price, and Dr. Susan Morrison, for their extraordinary support during my undergraduate and graduate careers. Thank you to my family, who were there for me during the times when I did not think I could succeed, and every time when I did. Thank you to my supportive friends for sticking by my side in the most exciting and stressful years of my life. -

Fan Remake Films: Active Engagement with Popular Texts

FAN REMAKE FILMS: ACTIVE ENGAGEMENT WITH POPULAR TEXTS Emma Lynn A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2021 Committee: Jeffery Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin Radhika Gajjala © 2021 Emma Lynn All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeffery Brown, Advisor In a small town in Mississippi in 1982, eleven-year-old Chris Strompolos commissioned his friends Eric Zala and Jayson Lamb to remake his favorite film, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). This remake would dominate their summer vacations for the next seven years. Over thirty years later in January 2020, brothers Mason and Morgan McGrew completed their shot- for-shot live action remake of Toy Story 3 (2010). This project took them eight years. Fan remake films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Adaptation (1989) and Toy Story 3 in Real Life (2020) represent something unique in fan studies. Fan studies scholars, such as Henry Jenkins, have considered the many ways fans are an example of an active audience, appropriating texts for their own creative use. While these considerations have proven useful at identifying the participatory culture fans engage in, they neglect to consider fans that do not alter and change the original text in any purposeful way. Sitting at the intersection of fan and adaptation studies, I argue that these fan remake films provide useful insights into the original films, the fans’ personal lives, and fan culture at large. Through the consideration of fan remake films as a textual object, a process of creation, and a consumable media product, I look at how Raiders of the Lost Ark: The Adaptation and Toy Story 3 in Real Life reinforce the fans’ interpretations of the original films in a concrete way in their own lives and in the lives of those who watch. -

Show #1300 --- Week of 12/9/19-12/15/19

Show #1300 --- Week of 12/9/19-12/15/19 HOUR ONE--SEGMENTS 1-3 SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL________________ SEGMENT ONE: "Million Dollar Intro" - Ani DiFranco :55 in-studio n/a "Mr. Wendal"-Arrested Development 3:25 Unplugged Chrysalis "New Woman’s World"-The Avett Brothers 4:05 Closer Than Together Republic "Hello, I’m Right Here"-Tegan & Sara 3:05 Hey, I’m Just Like You Warner Brothers "Pity Party"-Lizzie No 3:35 Vanity self-released "Moon Is Rising"-The Head & The Heart 2:30 Lucid Shanachie ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: Outcue: " in-studio guest Tanya Tucker." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 20:14 ***PLAY CUSTOMIZED STATION ID INTO: SEGMENT TWO: "Inside Out (demo)" –Spoon 1:50 single only XL Recordings ***INTERVIEW & MUSIC: TANYA TUCKER ("High Ridin’ Heroes," "Wheels Of Laredo") in-studio interview/performance n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** The Ark/"2020 Ann Arbor Folk Festival" (:30) Outcue: " FindYourFolk." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 19:03 SEGMENT THREE: "I’ve Been Failing"-Nathaniel Rateliff & The Night Sweats 3:00 N.R. & N S Stax "Cold As It is"-The Lone Bellow (in-studio) 3:00 in-studio n/a "Walk Through Fire"-Yola (in-studio) 4:00 in-studio n/a "Any Old Time"-Sara Watkins (in-studio) 3:15 in-studio n/a ***MUSIC OUT AND INTO: ***NATIONAL SPONSOR BREAK*** Leon Speakers/"The Leon Loft" (:30) Outcue: " at LeonSpeakers.com." TOTAL TRACK TIME: 18:44 TOTAL TIME FOR HOUR ONE-55:00 acoustic café · p.o. box 7730 · ann arbor, mi 48107-7730 · 734/761-2043 · fax 734/761-4412 [email protected] ACOUSTIC CAFE, CONTINUED Page 2 Show #1300 --- Week of 12/9/19-12/15/19 HOUR TWO--SEGMENTS 4-6: SONG ARTIST LENGTH ALBUM LABEL________________ SEGMENT FOUR: "Every Night"-Paul McCartney 3:20 Unplugged (The Official Bootleg) Capitol "Dumb"-Nirvana 2:40 Unplugged In New York Geffen "Every Little Bit Hurts"-Alicia Keys 4:00 Unplugged J "San Francisco Bay Blues"-Eric Clapton 3:25 Unplugged Warner Brothers "Moonglow"-Tony Bennet & k.d. -

Making Your Own Drum Video by Wes Crawford

Making Your Own Drum Video BY WES CRawFORD ever mind a featured role opposite Once you have decided upon a type of RESOURCES Angelina Jolie in her next film; how drum video, it is important to formalize an A professional video might cost from Nmany of you feel that the epitome of idea for subject and content. The idea must $10,000–50,000 or more. Anything you can an appearance on the big (or small) screen be original, or at least expand in some im- accomplish on your own will save money involves you starring in your own drum portant manner upon prior topics. It is also down the line if you have competence in video? If you believe the chances for either important to consider the characteristics of each task. For instance, if you rent several of the above scenarios are next to impos- your target market, as these may affect the video cameras and take care to set up com- sible, let me tell you how I succeeded in the feasibility of your idea. plementary shots, you may not need to hire second one. It may be instructive to explain my video a film crew. However, you may end up with The digital age has revolutionized the category, idea, and target market. I chose bad lighting, unmatched cameras, focus video industry, similarly to the audio re- the instructional/training video category problems, etc. if you are inexperienced. cording industry, to the point that less than since I have neither a national reputation Don’t borrow a couple of camcorders $10,000 worth of gear can often accomplish nor any exceptional expertise in music his- from friends and expect your results to look today what $100,000+ accomplished only a tory or drumming technique, but I do teach like one of your favorite movies, unless that few years ago. -

Embodiment, Phenomenology and Listener Receptivity of Nirvana’S in Utero

‘WE FEED OFF EACH OTHER’: EMBODIMENT, PHENOMENOLOGY AND LISTENER RECEPTIVITY OF NIRVANA’S IN UTERO Christopher Martin A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2006 Committee: Jeremy Wallach Becca Cragin Angela Nelson ii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Despite the fact that listening to recorded music is a predominant form of human interaction with music in general, music scholarship often continues to classify listening as a passive form of reception in comparison to the “activity” of actual music performance. This thesis presents the idea that music listening is actually an embodied and agentive form of reception that varies according to different listeners, their listening strategies, and other surrounding contexts. In order to provide detailed analysis of this assertion, Nirvana’s 1993 album In Utero is the primary recording that this thesis examines, arguing that the album contains specific embodied properties that ultimately allow for embodied forms of listening and responses within the musical experience. Phenomenological reasoning and scholarship from popular music studies, history, cultural studies, and other humanities fields contribute to the central argument. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe an oversized thank you to the following friends and family for their support: Pat and Priscilla Martin, Veronica Martin, Linda Coleson, and my colleagues in the Popular Culture department. Aaron Weinacht and Patrick Blythe earn special thanks for their continuing willingness to participate in arguments and theories that, as always, range from prescient to ridiculous. Kandace Virgin also deserves my thanks and love for patiently tolerating my stubbornness and need to constantly work ahead, as well as my other idiosyncrasies. -

Starving to Death Little by Little Every

STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY IMPACTS ON HUMAN RIGHTS CAUSED BY THE USINA TRAPICHE COMPANY TO A FISHING COMMUNITY IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF SIRINHAÉM/STATE OF PERNAMBUCO, BRAZIL 1 STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY IMPACTS ON HUMAN RIGHTS CAUSED BY THE USINA TRAPICHE COMPANY TO A FISHING COMMUNITY IN THE MUNICIPALITY OF SIRINHAÉM/STATE OF PERNAMBUCO, BRAZIL Pastoral Land Commission Northeast Regional Office II RECIFE, 2016 EDITORIAL STAFF STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY: Impacts on human rights caused by the Usina Trapiche company to a fishing community in the municipality of Sirinhaém/state of Pernambuco, Brazil PRepARED BY: Pastoral Land Commission - Northeast Regional Office II SUppORTED BY: OXFAM America and OXFAM Brasil. This report was financially supported by Oxfam, but does not necessarily represents Oxfam’s views. TEXTS: Eduardo Fernandes de Araújo Gabriella Rodrigues Santos Luísa Duque Belfort Mariana Vidal Maia Marluce Cavalcanti Melo Renata Costa C. de Albuquerque Thalles Gomes Camelo CONSULTANTS: Daniel Viegas Flávio Wanderley da Silva Frei Sinésio Araujo João Paulo Medeiros José Plácido da Silva Junior Padre Tiago Thorlby TEXT EDITING: Antônio Canuto Veronica Falcão TRANSLATION: Luiz Marcos Bianchi Leite de Vasconcelos PROOFREADING: Gabriella Muniz GRAPHIC DESIGN AND EDITING: Isabela Freire PRINTED BY: Gráfica e Editora Oito de Março COVER/BACK COVER PHOTO: CPT - Nordeste 2 PHOTOS: Collection of the Pastoral Land Commission - Northeast Regional Office II Renata Costa C. de Albuquerque José Plácido da Silva Junior Father James Thorlby ISBN: 978-85-62093-09-8 Pastoral Land Commission Northeast Office II - www.cptne2.org.br RecIFE - 2016 FOREWORD STARVING TO DEATH LITTLE BY LITTLE EVERY DAY This publication provides a living picture of but also ethanol to supply the increasing fleet of the tragic story of families expelled from the vehicles in Brazil and in the world.