Visual Essays on the Music Video Archive of Kendrick Lamar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON

01-2017 Index Good Short Total Song 1 36 0 36 LOUISA JOHNSON - SO GOOD 2 34 0 34 RUDI BUČAR & ISTRABAND - GREVA NAPREJ 3 33 0 33 RAG'N'BONE MAN - HUMAN 4 33 0 33 DISTURBED - THE SOUND OF SILENCE 5 30 0 30 ED SHEERAN - SHAPE OF YOU 6 28 0 28 ROBBIE WILLIAMS - LOVE MY LIFE 7 28 0 28 RICKY MARTIN & MALUMA - VENTE PA'CA 8 27 0 27 ALYA - SRCE ZA SRCE 9 26 0 26 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - STARBOY 10 25 0 25 STING - I CAN'T STOP THINKING ABOUT YOU 11 23 0 23 RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS - DARK NECESSITIES 12 22 0 22 RED HOT CHILLI PEPPERS - SICK LOVE 13 22 0 22 LEONART - POJEM ZATE 14 22 0 22 NEISHA - VRHOVI 15 22 0 22 LUKAS GRAHAM - 7 YEARS 16 22 0 22 LOS VENTILOS - ČAS 17 21 0 21 RUSKO RICHIE - S TOBOM 18 21 0 21 TABU - PRVI ZADNJI 19 20 0 20 FILATOV & KARAS - TELL IT TO MY HEART 20 20 0 20 TWENTY ONE PILOTS - HEATHENS 21 19 0 19 OMAR NABER - POSEBEN DAN 22 19 0 19 X AMBASSADORS - RENEGADES 23 19 0 19 SHAKIRA - TRY EVERYTHING 24 18 0 18 NIET - OPROSTI MI 25 18 0 18 SIDDHARTA - LEDENA 26 18 0 18 MANCA ŠPIK & ISAAC PALMA - OBA 27 17 0 17 PANDA - SANJE 28 17 0 17 KINGS OF LEON - WASTE A MOMENT 29 17 0 17 LEONART - DANES ME NI 30 17 0 17 CLEAN BANDIT & SEAN PAUL & ANNE MARIE - ROCKBABY 31 17 0 17 HONNE - GOOD TOGETHER 32 16 0 16 ČEDAHUČI - ČE HOČEŠ GREM 33 16 0 16 LADY GAGA - PERFECT ILLUSION 34 16 0 16 MAGNIFICO - KUKU LELE 35 15 0 15 JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE - CAN'T STOP THE FEELINGS 36 15 0 15 BON JOVI - REUNION 37 15 0 15 NEK - UNICI 38 15 0 15 STRUMBELLAS - SPIRIT 39 15 0 15 PARSON JAMES - SAD SONG 40 15 0 15 WEEKEND & DAFT PUNK - I FEEL IT COMING 41 15 0 15 AVIICI & CONRAD SWELL - TASTE THE FEELING 42 15 0 15 DAVID & ALEX & SAM - TA OBČUTEK 43 14 0 14 I.C.E. -

Taking Intellectual Property Into Their Own Hands

Taking Intellectual Property into Their Own Hands Amy Adler* & Jeanne C. Fromer** When we think about people seeking relief for infringement of their intellectual property rights under copyright and trademark laws, we typically assume they will operate within an overtly legal scheme. By contrast, creators of works that lie outside the subject matter, or at least outside the heartland, of intellectual property law often remedy copying of their works by asserting extralegal norms within their own tight-knit communities. In recent years, however, there has been a growing third category of relief-seekers: those taking intellectual property into their own hands, seeking relief outside the legal system for copying of works that fall well within the heartland of copyright or trademark laws, such as visual art, music, and fashion. They exercise intellectual property self-help in a constellation of ways. Most frequently, they use shaming, principally through social media or a similar platform, to call out perceived misappropriations. Other times, they reappropriate perceived misappropriations, therein generating new creative works. This Article identifies, illustrates, and analyzes this phenomenon using a diverse array of recent examples. Aggrieved creators can use self-help of the sorts we describe to accomplish much of what they hope to derive from successful infringement litigation: collect monetary damages, stop the appropriation, insist on attribution of their work, and correct potential misattributions of a misappropriation. We evaluate the benefits and demerits of intellectual property self-help as compared with more traditional intellectual property enforcement. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KP7TR8W Copyright © 2019 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Inc. -

USG Elects Jorgensen, Dimcevski As Senators Creates New Concerns (P

VOLUME 112 • ISSUE 11 BARUCH COLLEGE’S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER DECEMBER 4, 2017 OPINIONS 5 Water contamination USG elects Jorgensen, Dimcevski as senators creates new concerns (p. 5) Chemical companies that prioritize prof- its over people are introducing toxicity into public water supplies. Cor- porations like those that in- troduced lead into Flint, Michigan, need to be tightly regulated to prevent more dangerous incidents. BUSINESS 7 FCC chairman plans to revoke net neutrality (p. 7) FCC Chairman Ajit Pai has an- nounced his aim to revoke net neutrality NICOLE PUNG | THE TICKER regulations. If these rules are Jorgensen, left, and Dimcevski, right, join the table at the end of the Fall semester, and will continue to stay on as senators until the end of the Spring semester. repealed, the internet could BY BIANCA MONTEIRO be throttled by NEWS ASSISTANT internet service providers. Baruch College’s Undergraduate Student Government offi cially elected two new representative senators — Alexander Dimcevski and Emma Jor- gensen — on Nov. 21 during its senate meeting. A total of 14 students ran for the positions. Jorgensen was also confi rmed as chair of appeals, a position ARTS & STYLE 10 she took over after serving as interim chair for two weeks. Th e vacancy opened when former Treasurer Ehtasham Bhatti resigned and former Chair of DC superheroes unite in Appeals Suzanna Egan took his place on Nov. 9. Th e second vacancy followed the resignation of former Representative Sen. Josue Mendez. Th e two Justice League (p. 11) senators offi cially began serving on the table in the following senate meeting on Nov. -

Uila Supported Apps

Uila Supported Applications and Protocols updated Oct 2020 Application/Protocol Name Full Description 01net.com 01net website, a French high-tech news site. 050 plus is a Japanese embedded smartphone application dedicated to 050 plus audio-conferencing. 0zz0.com 0zz0 is an online solution to store, send and share files 10050.net China Railcom group web portal. This protocol plug-in classifies the http traffic to the host 10086.cn. It also 10086.cn classifies the ssl traffic to the Common Name 10086.cn. 104.com Web site dedicated to job research. 1111.com.tw Website dedicated to job research in Taiwan. 114la.com Chinese web portal operated by YLMF Computer Technology Co. Chinese cloud storing system of the 115 website. It is operated by YLMF 115.com Computer Technology Co. 118114.cn Chinese booking and reservation portal. 11st.co.kr Korean shopping website 11st. It is operated by SK Planet Co. 1337x.org Bittorrent tracker search engine 139mail 139mail is a chinese webmail powered by China Mobile. 15min.lt Lithuanian news portal Chinese web portal 163. It is operated by NetEase, a company which 163.com pioneered the development of Internet in China. 17173.com Website distributing Chinese games. 17u.com Chinese online travel booking website. 20 minutes is a free, daily newspaper available in France, Spain and 20minutes Switzerland. This plugin classifies websites. 24h.com.vn Vietnamese news portal 24ora.com Aruban news portal 24sata.hr Croatian news portal 24SevenOffice 24SevenOffice is a web-based Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. 24ur.com Slovenian news portal 2ch.net Japanese adult videos web site 2Shared 2shared is an online space for sharing and storage. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

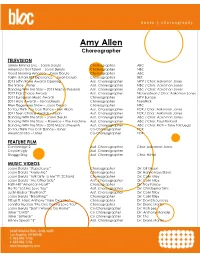

Amy Allen Choreographer

Amy Allen Choreographer TELEVISION Jimmy Kimmel Live – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC America’s Got Talent – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC Good Morning America – Jason Derulo Choreographer ABC 106th & Park BET Experience – Jason Derulo Choreographer BET 2013 MTV Movie Awards Opening Asst. Choreographer MTV / Chor: Aakomon Jones The Voice – Usher Asst. Choreographer NBC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – 2013 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2012 Kids Choice Awards Asst. Choreographer Nickelodeon / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 European Music Awards Choreographer MTV Europe 2011 Halo Awards – Jason Derulo Choreographer TeenNick Ellen Degeneres Show – Jason Derulo Choreographer NBC So You Think You Can Dance – Keri Hilson Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones 2011 Teen Choice Awards – Jason Asst. Choreographer FOX / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Jason Derulo Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Aakomon Jones Dancing With the Stars – Florence + The Machine Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Paul Kirkland Dancing With the Stars – 2010 Macy’s Presents Asst. Choreographer ABC / Chor: Rich + Tone Talauega So You Think You Can Dance – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX American Idol – Usher Co-Choreographer FOX FEATURE FILM Centerstage 2 Asst. Choreographer Chor: Aakomon Jones Coyote Ugly Asst. Choreographer Shaggy Dog Asst. Choreographer Chor: Hi Hat MUSIC VIDEOS Jason Derulo “Stupid Love” Choreographer Dir: Gil Green Jason Derulo “Marry Me” Choreographer Dir: Hannah Lux Davis Jason Derulo “Talk Dirty To Me” ft. 2Chainz Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Jason Derulo “The Other Side” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Colin Tilley Faith Hill “American Heart” Choreographer Dir: Trey Fanjoy Ne-Yo “Let Me Love You” Asst. Choreographer Dir: Christopher Sims Justin Bieber “Boyfriend” Asst. -

From Testimony to Story Video Interviews About Nazi Crimes

Education with Testimonies FROM TESTIMONY TO STORY Video Interviews about Nazi Crimes. Perspectives and Experiences in Four Countries edited by Dagi Knellessen and Ralf Possekel The stories of Holocaust survivors and others who were persecuted by the Nazis are an invaluable resource for understanding what effect persecution had on victims and how they dealt with this experience over time. In recent decades, researchers in many countries began videotaping contemporary witnesses as they told their stories, allowing their voices to be heard, when personal encounters are no longer possible. In the interviews, biographical narratives and personal memories are used to document the mass crimes committed by the Nazis and also to illuminate how survivors processed these memories in their lifetime. This multi-faceted historical source poses special challenges to educational work. This volume reflects international developments, trends and debates about the videotaped contemporary witness interviews and their digital archives. Different interview collections and educational approaches from Israel, the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany are presented. These essays document the exchange that took place between education experts from these four countries as part of the series Entdecken und Verstehen. Bildungs- arbeit mit Zeugnissen von Opfern des Nationalsozialismus (“Discovering and Understanding: Educational Work with Testimonials from Victims of National Socialism”) that was initiated and organized by the Foundation EVZ in 2010 and 2011. Education -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

Unit 5: Understanding and Resolving Guest Problems

Unit 5: Understanding and Resolving Guest Problems Project Hotel T.E.A.C.H Curriculum Center for Immigrant Education and Training (ACE) LaGuardia Community College Hotel TEACH Lesson Plan Unit 5, Lesson 1 Career Counseling: Listening with Empathy Objectives Sts will learn to resolve problems and listen empathetically for improved customer service. EFF Skill Sets addressed Cooperate with Others: Try to adjust one’s actions to take into the account the needs of others and/or the task to be accomplished. Industry Skill Sets addressed Resolve Guest Problems Exceed Customer Expectations Activity 1: Empathy Skills T introduces another important component of active listening: empathy. T asks the Sts to define “empathy.” As Sts call out answers, T leads responses towards the following definition and writes it on the board. Empathy is the ability to recognize and understand the emotions, beliefs, moods and desires of another person. Empathy is often characterized as the ability to “put oneself into another’s shoes.” T elicits from Sts the reasons why it would be important for hotel workers to have empathy. Some examples might be as follows: 1. Listening empathetically makes people feel as if they are truly being heard and that their needs will be taken care of. 2. Listening with empathy gives guests a positive experience of the hotel and of you as a worker. Guests will always remember the worker who truly listened and cared about their problem, as opposed to the worker who offers a quick solution. 3. When you acknowledge how people are feeling, you reassure them that they are understood. -

Progressive Traits in the Music of Dream Theater Thesis Written for the Bachelor of Musicology University of Utrecht Supervised by Professor Karl Kügle June 2013 1

2013 W. B. van Dijk 3196372 PROGRESSIVE TRAITS IN THE MUSIC OF DREAM THEATER THESIS WRITTEN FOR THE BACHELOR OF MUSICOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF UTRECHT SUPERVISED BY PROFESSOR KARL KÜGLE JUNE 2013 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Foreword .......................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 2: A definition of progressiveness ......................................................................................... 3 2.1 – Problematization ..................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 - A brief history of progressive rock ......................................................................................... 4 2.3 – Progressive rock in the classic age: 1968-1978 ...................................................................... 5 2.4 - A selective list of progressive traits ........................................................................................ 6 Chapter 3: Progressive Rock and Dream Theater ............................................................................... 9 3.1 – A short biography of the band Dream Theater ....................................................................... 9 3.2 - Progressive traits in Scenes from a Memory ......................................................................... 10 3.3 - Progressive traits in ‗The Dance of Eternity‘ ........................................................................ 12 Chapter 4: Discussion & -

M I K E S a R K I S S I a N Credits

MIKE SARKISSIAN CREDITS _____________________________________________________________________________ EXECUTIVE PRODUCER / PRODUCER FILM The White Stripes Under Great White Northern Lights Emmett Malloy Jack Johnson En Concert Emmett Malloy Jack Johnson A Weekend at the Greek Emmett Malloy Jack White Jack White Kneeling at The Anthem Emmett Malloy TV Paramount Dream: Birth of the Modern Athlete The Malloy Brothers National Geographic Breakthrough Season 2 Series Producer Revolution Studios Pilot – Everyday People Tim Wheeler GSN / Revolution Studios Drew Carey’s Improv-A-ganza 40 eps Liz Zannin The Dead Weather Live at the ROXY Tim Wheeler Jack Johnson Kokua Festival 05-09 Emmett Malloy From The Basement Raconteurs / Kills / Fleet Foxes Nigel Godrich From The Basement Queens of the Stone Age Nigel Godrich Sundance Channel 5 Years of Change – KOKUA Emmett Malloy Selena Gomez Girl Meets World – Disney Channel Tim Wheeler James Blunt Live & SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler Disney Channel Radio Disney Concert Special Tim Wheeler Nickelback Live at Home Nigel Dick Marie Digby Live At Rick Ruben Studios Mike Piscitelli Grace Potter Live In Burlington Tim Wheeler Alpha Rev Live @SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler Kate Vogel Live @SPPP Studios Tim Wheeler ZZ Ward Live @ The Troubadour Tim Wheeler Nick Jonas Live @ Capitol Records Giles Dunning Grace Potter Live @ The Waterfront Tim Wheeler R5 Live @ the O2 London Tim Wheeler COMMERCIALS Honda Happy Honda Days ’19 Campain Jed Hathaway Apple Apple TV+ 2019 March Launch Robin Cosimir Waze Waze Carpool Jeff + Pete Accenture Talent, Resilience, Disruption Jordan Bahat Google Google Cloud Jordan Bahat Amazon Fire TV Twin Peaks Pie Shop, Playlist Jeff + Pete Always Prepared, No Chance Whip It, Whip it Good Sharknado by the Sea Chicken Little Fingers Dove Real Moms Acura Emotion Is In IBM / Watson Not Easy Nicolas Davenel Max Factor Miracle Touch Camilla Akrins Visa Snapchat / Olympics Giles Dunning McDonalds Fans vs Critics Jordan Bahat Navy Federal Credit Union Veterans Bond Jeff + Pete Dr. -

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer

ALEX DELGADO Production Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE KEYS OF CHRISTMAS David Meyers YouTube Red Feature OPENING NIGHTS Isaac Rentz Dark Factory Entertainment Feature Los Angeles Film Festival G.U.Y. Lady Gaga Rocket In My Pocket / Riveting Short Film Entertainment MR. HAPPY Colin Tilley Vice Short Film COMMERCIALS & MUSIC VIDEOS SOL Republic Headphones, Kraken Rum, Fox Sports, Wendy’s, Corona, Xbox, Optimum, Comcast, Delta Airlines, Samsung, Hasbro, SONOS, Reebok, Veria Living, Dropbox, Walmart, Adidas, Go Daddy, Microsoft, Sony, Boomchickapop Popcorn, Macy’s Taco Bell, TGI Friday’s, Puma, ESPN, JCPenney, Infiniti, Nicki Minaj’s Pink Friday Perfume, ARI by Ariana Grande; Nicki Minaj - “The Boys ft. Cassie”, Lil’ Wayne - “Love Me ft. Drake & Future”, BOB “Out of My Mind ft. Nicki Minaj”, Fergie - “M.I.L.F.$”, Mike Posner - “I Took A Pill in Ibiza”, DJ Snake ft. Bipolar Sunshine - “Middle”, Mark Ronson - “Uptown Funk”, Kelly Clarkson - “People Like Us”, Flo Rida - “Sweet Spot ft. Jennifer Lopez”, Chris Brown - “Fine China”, Kelly Rowland - “Kisses Down Low”, Mika - “Popular”, 3OH!3 - “Back to Life”, Margaret - “Thank You Very Much”, The Lonely Island - “YOLO ft. Adam Levine & Kendrick Lamar”, David Guetta “Just One Last Time”, Nicki Minaj - “I Am Your Leader”, David Guetta - “I Can Only Imagine ft. Chris Brown & Lil’ Wayne”, Flying Lotus - “Tiny Tortures”, Nicki Minaj - “Freedom”, Labrinth - “Last Time”, Chris Brown - “She Ain’t You”, Chris Brown - “Next To You ft. Justin Bieber”, French Montana - “Shot Caller ft. Diddy and Rick Ross”, Aura Dione - “Friends ft. Rock Mafia”, Common - “Blue Sky”, Game - “Red Nation ft. Lil’ Wayne”, Tyga “Faded ft.