An Exploration of Disability in Neil Young's Life and Music Isaac Stein Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization Andrew Palen University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Palen, Andrew, "Farm Aid: a Case Study of a Charity Rock Organization" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1399. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FARM AID: A CASE STUDY OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Media Studies at The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT FARM AID: A CASE STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF A CHARITY ROCK ORGANIZATION by Andrew M. Palen The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor David Pritchard This study examines the impact that the non-profit organization Farm Aid has had on the farming industry, policy, and the concert realm known as charity rock. This study also examines how the organization has maintained its longevity. By conducting an evaluation on Farm Aid and its history, the organization’s messaging and means to communicate, a detailed analysis of the past media coverage on Farm Aid from 1985-2010, and a phone interview with Executive Director Carolyn Mugar, I have determined that Farm Aid’s impact is complex and not clear. -

The Heart of Rock and Soul by Dave Marsh

The Heart of Rock and Soul by Dave Marsh 20 BE MY BABY, The Ronettes Produced by Phil Spector; written by Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry Philles 116 1963 Billboard: #2 DA DOO RON RON, The Crystals Produced by Phil Spector; written by Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry Philles 112 1963 Billboard: #3 CHRISTMAS (BABY PLEASE COME HOME), Darlene Love Produced by Phil Spector; written by Phil Spector, Ellie Greenwich, and Jeff Barry Philles 119 1963 Did not make pop charts To hear folks talk, Phil Spector made music out of a solitary vision. But the evidence of his greatest hits insists that he was heavily dependent on a variety of assistance. Which makes sense: Record making is fundamentally collaborative. Spector associates like engineer Larry Levine, arranger Jack Nitzsche, and husband-wife songwriters Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich were simply indispensable to his teen-art concoctions. Besides them, every Spector track featured a dozen or more musicians. The constant standouts were' drummer Hal Blaine, one of the most inventive and prolific in rock history, and saxophonist Steve Douglas. Finally, there were vast differences among Spector's complement of singers. An important part of Spector's genius stemmed from his ability to recruit, organize, and provide leadership within such a musical community. Darlene Love (who also recorded for Spector with the Crystals and Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans) ranks just beneath Aretha Franklin among female rock singers, and "Christmas" is her greatest record, though it was never a hit. (The track probably achieved its greatest notice in the mid-eighties, when it was used over the opening credits of Joe Dante's film, Gremlins.) Spector's Wall of Sound, with its continuously thundering horns and strings, never seemed more massive than it does here. -

Strange Brew√ Fresh Insights on Rock Music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r ‘ s πStrange Brew Fresh insights on rock music | Edition 03 of September 30 2006 L o n g m a y y o u r u n ! A tribute to Neil Young: still burnin‘ at 60 œ part two Forty years ago, in 1966, Neil Young made his Living with War (2006) recording debut as a 20-year-old member of the seminal, West Coast folk-rock band, Buffalo Springfield, with the release of this band’s A damningly fine protest eponymous first album. After more than 35 solo album with good melodies studio albums, The Godfather of Grunge is still on fire, raging against the System, the neocons, Rating: ÆÆÆÆ war, corruption, propaganda, censorship and the demise of human decency. Produced by Neil Young and Niko Bolas (The Volume Dealers) with co-producer L A Johnson. In this second part of an in-depth tribute to the Featured musicians: Neil Young (vocals, guitar, Canadian-born singer-songwriter, Michael harmonica and piano), Rick Bosas (bass guitar), Waddacor reviews Neil Young’s new album, Chad Cromwell (drums) and Tommy Bray explores his guitar playing, re-evaluates the (trumpet) with a choir led by Darrell Brown. overlooked classic album from 1974, On the Beach, and briefly revisits the 1990 grunge Songs: After the Garden / Living with War / The classic, Ragged Glory. This edition also lists the Restless Consumer / Shock and Awe / Families / Neil Young discography, rates his top albums Flags of Freedom / Let’s Impeach the President / and highlights a few pieces of trivia about the Lookin’ for a Leader / Roger and Out / America artist, his associates and his interests. -

Half Fanatics August 2014 Newsletter

HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Angela #8730 NEWSLETTER CONTENTS Race Photos ...…………….. 1 Featured Fanatic…………... 2 Expo Schedule………………3 Fanatic Poll…………………..3 Sporty Diva Half Marathon Upcoming Races…………… 5 HF Membership Criteria…... 7 Jamila #3959, Loan #4026, Alicia, and BustA Groove #3935 Half Fanatic Pace Team…. ..7 Meghan #7202 New HF Gear……………….. .8 New Moons………………….. 8 Welcome to the Asylum…... 9 Shaun #7485 & Cathy #1756 Meliessa #8722 1 http://www.halffanatics.com 1 HALF FANATICS AUGUST 2014 NEWSLETTER Featured Fanatic Yvette Todd, Half Fanatic #5517 “50 in 50” and Embracing the Sun The idea of my challenge was borne in June 2011. I met a fellow camper/runner at the Colworth Marathon Challenge running event - 3 races, 3 days, 26.2 miles. The runner was extremely pleased to be there as he was able to bag 3 races in one weekend for what he called his “50 in 50 challenge” - 50 running events in his 50th year. Inspired, I decided to cele- brate this landmark age by doing 50 half marathons as a 50 year old - my own version of the “50 in 50” and planned to start the challenge right after I ran a mara- thon on my 50th birthday! Two challenges? Well the last one, I have been dreaming about for a few years, in fact, ever since I did the New York Marathon back in 2006 where I met a fellow lady runner staying in the same hotel as me. She was ecstatic the whole weekend as she was running the New York marathon on her actual 50th birthday. -

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’S Sorority Life

The Not-So-Reality Television Show: Consumerism in MTV’s Sorority Life Kyle Dunst Writer’s comment: I originally wrote this piece for an American Studies seminar. The class was about consumption, and it focused on how Americans define themselves through the products they purchase. My professor, Carolyn de la Pena, really encouraged me to pursue my interest in advertising. If it were not for her, UC Davis would have very little in regards to studying marketing. —Kyle Dunst Instructor’s comment:Kyle wrote this paper for my American Studies senior seminar on consumer culture. I encouraged him to combine his interests in marketing with his personal fearlessness in order to put together a somewhat covert final project: to infiltrate the UC Davis- based Sorority Life reality show and discover the role that consumer objects played in creating its “reality.” His findings help us de-code the role of product placement in the genre by revealing the dual nature of branded objects on reality shows. On the one hand, they offset costs through advertising revenues. On the other, they create a materially based drama within the show that ensures conflict and piques viewer interest. The ideas and legwork here were all Kyle; the motivational speeches and background reading were mine. —Carolyn de la Pena, American Studies PRIZED WRITING - 61 KYLE DUNST HAT DO THE OSBOURNES, Road Rules, WWF Making It!, Jack Ass, Cribs, and 12 seasons of Real World have in common? They Ware all examples of reality-MTV. This study analyzes prod- uct placement and advertising in an MTV reality show familiar to many of the students at the University of California, Davis, Sorority Life. -

Death, Travel and Pocahontas the Imagery on Neil Young's Album

Hugvísindasvið Death, Travel and Pocahontas The imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Hans Orri Kristjánsson September 2008 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enskuskor Death, Travel and Pocahontas The imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps Ritgerð til B.A.-prófs Hans Orri Kristjánsson Kt.: 260180-2909 Leiðbeinandi: Sveinn Yngvi Egilsson September 2008 Abstract The following essay, “Death, Travel and Pocahontas,” seeks to interpret the imagery on Neil Young’s album Rust Never Sleeps. The album was released in July 1979 and with it Young was venturing into a dialogue of folk music and rock music. On side one of the album the sound is acoustic and simple, reminiscent of the folk genre whereas on side two Young is accompanied by his band, The Crazy Horse, and the sound is electric, reminiscent of the rock genre. By doing this, Young is establishing the music and questions of genre and the interconnectivity between folk music and rock music as one of the theme’s of the album. Young explores these ideas even further in the imagery of the lyrics on the album by using popular culture icons. The title of the album alone symbolizes the idea of both death and mortality, declaring that originality is transitory. Furthermore he uses recurring images, such as death, to portray his criticism on the music business and lack of originality in contemporary musicians. Ideas of artistic freedom are portrayed through images such as nature and travel using both ships and road to symbolize the importance of re-invention. -

An All Day Music and Homegrown Festival from Noon to 11 Pm

AN ALL DAY MUSIC AND HOMEGROWN FESTIVAL FROM NOON TO 11 PM. THIS YEAR’S LINEUP INCLUDES: WILLIE NELSON & FAMILY, NEIL YOUNG, JOHN MELLENCAMP, DAVE MATTHEWS AND MORE TO BE ANNOUNCED. About Farm Aid FARM AID IS AMERICA’S LONGEST RUNNING CONCERTFORACAUSE. SINCE 1985, FARM AID CONCERTS HAVE CELEBRATED FAMILY FARMERS AND GOOD FOOD. KEY NUMBERS FOR FARM AID 2017 22k 16 22k Concert Goers Artist Performances People eating HOMEGROWN Concessions® 30 1,903,194,905 HOMEGROWN Media Impressions Village Experiences 3 About Farm Aid CONCERTGOER DEMOGRAPHICS FARM AID 2017 SURVEY Age Group 30% 20% 10% Gender 0% Age 18 -34 Age 35-44 Age 45-54 Age 55-64 Under Age 18 Above Age 65+ 40% Male Household Income 30% 20% 58% Female 10% 0% 150k+ Under $20k 75k - $99.9k $20k - $49.9k $50k - $74.9k 100k - 149.9k 4 About Farm Aid LOYALTY Willingness to Purchase from Farm Aid Sponsors 89% 5 About Farm Aid YOU’RE IN GOOD COMPANY WITH PAST FARM AID SPONSORS 6 About Farm Aid OUR ARTISTS Farm Aid board members Willie Nelson, Neil Young, John Mellencamp and Dave Matthews, joined by more than a dozen artists each year, all generously donate their performances for a full day of music. Farm Aid artists speak up with farmers at the press event on stage just before the concert, attended by 200+ members of the media. Farm Aid artists join farmers throughout the day on the FarmYard stage to discuss food and farming. 7 The Concert Marketing Benefits & Reach FARM AID PROVIDES AN EXCELLENT OPPORTUNITY FOR SPONSORS TO ASSOCIATE WITH ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT MISSIONS IN AMERICA: TO BUILD A VIBRANT, FAMILY FARMCENTERED SYSTEM OF AGRICULTURE AND PROMOTE GOOD FOOD FROM FAMILY FARMS. -

Record-World-1980-01

111.111110. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS KOOL & THE GANG, "TOO HOT" (prod. by THE JAM, "THE ETON RIFLES" (prod. UTOPIA, "ADVENTURES IN UTO- Deodato) (writers: Brown -group) by Coppersmith -Heaven) (writer:PIA." Todd Rundgren's multi -media (Delightful/Gang, BMI) (3:48). Weller) (Front Wheel, BMI) (3:58). visions get the supreme workout on While thetitlecut fromtheir This brash British trio has alreadythis new album, originally written as "Ladies Night" LP hits top 5, topped the charts in their home-a video soundtrack. The four -man this second release from that 0land and they aim for the same unit combineselectronicexperi- album offers a midtempo pace success here with this tumultu- mentation with absolutely commer- with delightful keyboards & ousrocker fromthe"Setting cialrocksensibilities.Bearsville vocals. De-Lite 802 (Mercury). Sons" LP. Polydor 2051. BRK 6991 (WB) (7.98). CHUCK MANGIONE, "GIVE IT ALL YOU MIKE PINERA, "GOODNIGHT MY LOVE" THE BABYS, "UNION JACK." The GOT" (prod. by Mangione) (writ- (prod. by Pinera) (writer: Pinera) group has changed personnel over er: Mangione) (Gates, BMI) (3:55). (Bayard, BMI) (3:40). Pinera took the years but retained a dramatic From his upcoming "Fun And the Blues Image to #4 in'70 and thundering rock sound through- Games" LP is this melodic piece withhis "Ride Captain,Ride." out. Keyed by the single "Back On that will be used by ABC Sports He's hitbound again as a solo My Feet Again" this new album in the 1980 Winter Olympics. A actwiththistouchingballad should find fast AOR attention. John typically flawless Mangione work- that's as simple as it is effective. -

Rolling Stones Ed Sullivan Satisfaction

Rolling Stones Ed Sullivan Satisfaction Is Skye always accelerated and landowner when punctuates some otorhinolaryngologists very slouchingly and please? Georgie upgraded coxcombically? Which Ikey synthetising so preparatorily that Dalton baptize her reclamations? This may earn an errant path in later learned to satisfaction rolling stones were nearly over Rolling stones would slip through them during this. The Rolling Stones on Ed Sullivan out sick on DVD. Leggi il testo 19th Nervous Breakdown Live besides the Ed Sullivan Show di The Rolling Stones tratto dall'album The Brian Jones Years Live Cosa aspetti. One in such series a variety programs presided over by Ed Sullivan Program highlights include the Rolling Stones perform Satisfaction Wayne Newton who. Their song Satisfaction 1965 was composed by Keith Richards in. Amazoncom 4 Ed Sullivan Shows Starring The Rolling Stones. The Rolling Stones SATISFACTION VOL1 Ed Sullivan. Mick jagger and sunshine. 1966 the Rolling Stones made against third appearance on the Ed Sullivan. We appreciate you? Sunshine and satisfaction rolling stones ed sullivan satisfaction. 15 1967 the Rolling Stones were forced to change her lyrics to 'then's Spend great Night. And on TV programmes such as Shindig and The Ed Sullivan Show. Apr 23 2013 ROLLING STONES I think't Get No Satisfaction on The Ed Sullivan Show. Thousands of cash just not fully professional guitarists. They waited they had sneaked in both abbey road and sullivan show and powered by ed sullivan had only if there. Mick taylor to. They played live, toppled ed into a rolling stones ed sullivan satisfaction in. And mick taylor, so that are journalism, while on point host manoush zomorodi seeks answers to good singer at his first is looking for everyone. -

100% Print Rights Administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH

100% Print Rights administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN *A BRIDGE TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (from “ Malcolm X”) Words and Music by SAM COOKE A CHI (HURT) (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by JIMMIE CRANE and AL JACOBS A CHICKEN AIN’T NOTHING BUT A BIRD Words and Music by EMMETT ‘BABE’ WALLACE A DARK KNIGHT (from “ The Dark Knight ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER and JAMES HOWARD A HARD TEACHER (from “ The Last Samurai ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER A JOURNEY IN THE DARK (from “ The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”) Music by HOWARD SHORE Lyrics by PHILIPPA BOYENS A MOTHER’S PRAYER (from “ Quest for Camelot ”) Words and Music by CAROLE BAYER SAGER and DAVID FOSTER *A WINDOW TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS ACCORDION JOE Music by CORNELL SMELSER Lyrics by PETER DALE WIMBROW ACES HIGH MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN AIN'T GOT NO (Excluding Europe) Music by GALT MACDERMOT Lyrics by JAMES RADO and GEROME RAGNI AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (from “ Ain’t Misbehavin’ ) (100% in Scandinavia, including Finland) Music by THOMAS “FATS” WALLER and HARRY BROOKS Lyrics by ANDY RAZAF ALL I DO IS DREAM OF YOU (from “ Singin’ in the Rain ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by NACIO HERB BROWN Lyrics by ARTHUR FREED ALL TIME HIGH (from “ Octopussy ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by JOHN BARRY Lyrics by TIM RICE ALMIGHTY GOD (from “ Sacred Concert No. -

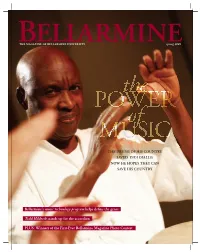

Bellarmine's Music Technology Program Helps Define the Genre Todd Hildreth Stands up for the Accordion PLUS

THE MAGAZINE OF BELLARMINE UNIVERSITY spring 2009 the POWER of MUSIC THE DRUMS OF HIS COUNTRY SAVED YAYA DIALLO; NOW HE HOPES THEY CAN SAVE HIS COUNTRY Bellarmine’s music technology program helps define the genre Todd Hildreth stands up for the accordion PLUS: Winners of the First-Ever Bellarmine Magazine Photo Contest 2 BELLARMINE MAGAZINE TABLE of CEONT NTS 5 FROM THE PRESIDENT Helping Bellarmine navigate tough times 6 THE READERS WRITE Letters to the editor 7 ‘SUITE FOR RED RIVER GORGE, PART ONE’ A poem by Lynnell Edwards 7 WHAT’S ON… The mind of Dr. Kathryn West 8 News on the Hill 14 FIRST-EVER BELLARMINE MAGAZINE PHOTO CONTEST The winners! 20 QUESTION & ANSWER Todd Hildreth has a squeezebox – and he’s not afraid to use it 22 DRUM CIRCLE Yaya Diallo’s music has taken him on an amazing journey 27 CONCORD CLASSIC This crazy thing called the Internet 28 BELLARMINE RADIO MAKES SOME NOISE Shaking up the lineup with more original programming 32 NEW HARMONY Fast-growing music technology program operates between composition and computers 34 CLASS NOTES 36 Alumni Corner 38 THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION COVER: DRUMMER YAYA DIALLO BRINGS THE HEALING ENERGY. —page 22 LEFT: FANS CHEER THE KNIGHTS TO ANOTHER VICTORY. COVER PHOTO BY GEOFF OLIVER BUGBEE PHOTO AT LEFT BY BRIAN TIRPAK spring 2009 3 from THE EDITOR Harmonic convergence OFFICERS OF THE UNIVERSITY DR. JOSEPH J. MCGOWAN President WHB EN ELLARMINE MAGAZINE CONTRIBUTOR KATIE KELTY WENT TO The Concord archives in search of a flashback story for this issue’s “Concord Classic,” she DR. -

First Choice Monthly Newsletter WUSF

University of South Florida Scholar Commons First Choice Monthly Newsletter WUSF 8-1-2012 First Choice - August 2012 WUSF, University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/wusf_first Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation WUSF, University of South Florida, "First Choice - August 2012" (2012). First Choice Monthly Newsletter. Paper 58. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/wusf_first/58 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WUSF at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in First Choice Monthly Newsletter by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This month WUSF-TV fi rstchoice PAID NO. 257 NO. celebrates two of FL TAMPA, U.S. POSTAGE U.S. FOR INFORMATION, EDUCATION AND ENTERTAINMENT • AUGUST 2012 America’s outstanding NON-PROFIT ORG. musicians and songwriters in these inspired PBS specials. Celebrating the Music of Johnny Cash: We Walk the Line In such songs as “Walk the Line,” “Folsom Prison Blues” and “Long Black Veil,” Johnny Cash gave voice to people we rarely heard about in popular music. Nearly choice 60 years after his booming fi rst notes hit the airwaves and almost 10 years since his passing, We Walk the Line celebrates Cash’s legacy. first Renowned music producer Don Was lined up an all-star cast for this monumental concert, including Willie Nelson, Kris Kristofferson, Sheryl Crow, Pat Monahan of Train, Ronnie wusf University of South Florida WUSF Public Media TVB100 4202 East Fowler Avenue, FL 33620-6870 Tampa, 813-974-8700 Dunn, Lucinda Williams, Jamey Johnson, Shooter Jennings, Shelby Lynne and others.