Introduction to Asthma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caring for Children with Special Needs ALLERGIES and ASTHMA

caring for children with special needs ALLERGIES AND ASTHMA We don’t usually think of children with allergies or asthma as children with “special needs,” but they certainly are. In fact, children with these conditions are probably the most frequently encountered “special needs” children. Child care providers can do a great deal to help individual children manage their specific allergy or asthma needs and feel more comfortable in a child care setting. Allergies wastes. Every house has them, no matter how clean. Other inhaled Children with allergies face the allergens include mold, pollen (hay same social difficulties as do adults, fever), animal dander (especially but they have less maturity and from cats), chemicals, and per emotional resources to deal with fumes. them. Children find that they cannot eat what their friends eat or The most common allergy symp cannot play outside during some toms are seasons. Until a child is mature � a clear, runny nose and enough to understand why she sneezing, cannot do something, you must be � itchy or stuffed-up nose or careful to help the child through the itchy, runny eyes, and difficulties. Start teaching a child early on about what he is allergic to; � asthma (remember that not all you will not always be able to people with asthma have monitor everything. allergies and not all allergies Some foods can cause a life cause or develop into asthma). threatening reaction. The mouth, throat, and bronchial tubes swell enough to interfere with breathing. Strategies for inclusion The person may wheeze or faint. Some parents have found that by Often there are generalized hives volunteering to bring food to and/or a swollen face. -

Symptoms Related to Asthma and Chronic Bronchitis in Three Areas of Sweden

Eur Respir J, 1994, 7, 2146–2153 Copyright ERS Journals Ltd 1994 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.94.07122146 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 Symptoms related to asthma and chronic bronchitis in three areas of Sweden E. Björnsson*, P. Plaschke**, E. Norrman+, C. Janson*, B. Lundbäck+, A. Rosenhall+, N. Lindholm**, L. Rosenhall+, E. Berglund++, G. Boman* Symptoms related to asthma and chronic bronchitis in three areas of Sweden. E. Björnsson, *Dept of Lung Medicine and Asthma P. Plaschke, E. Norrman, C. Janson, B. Lundbäck, A. Rosenhall, N. Lindholm, L. Research Center, Akademiska sjukhu- Rosenhall, E. Berglund, G. Boman. ERS Journals Ltd 1994. set, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. ABSTRACT: Does the prevalence of respiratory symptoms differ between regions? **Asthma and Allergy Research Center, Sahlgren's Hospital, University of Göteborg, As a part of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey, we present data Göteborg, Sweden. +Dept of Pulmonary from an international questionnaire on asthma symptoms occurring during a 12 Medicine and Allergology, Univer- month period, smoking and symptoms of chronic bronchitis. The questionnaire was sity Hospital of Northern Sweden, Umeå, mailed to 10,800 persons aged 20–44 yrs living in three regions of Sweden (Västerbotten, Sweden. ++Dept of Pulmonary Medicine, Uppsala and Göteborg) with different environmental characteristics. The total Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, response rate was 86%. Sweden. Wheezing was reported by 20.5%, and the combination of wheezing without a Correspondence: E. Björnsson, Dept of cold and wheezing with breathlessness by 7.4%. The use of asthma medication was Lung Medicine, Akademiska sjukhuset, S- reported by 5.3%. -

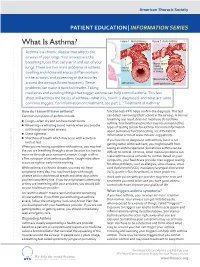

What Is Asthma? Figure 1

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES What Is Asthma? Figure 1. Normal Airway Figure 2. Acute Asthma Asthma is a chronic disease that affects the airways of your lungs. Your airways are the breathing tubes that carry air in and out of your Muscle spasm causing lungs. There are two main problems in asthma: relaxed narrowing muscles swelling and increased mucus (inflammation) of airways in the airways, and squeezing of the muscles Mucus build up around the airways (bronchospasm). These open airways Swelling/inammation problems can make it hard to breathe. Taking medicines and avoiding things that trigger asthma can help control asthma. This fact sheet will address the basics of asthma—what it is, how it is diagnosed, and what are some common triggers. For information on treatment, see part 2, “Treatment of Asthma”. How do I know if I have asthma? function test–PFT) helps confirm the diagnosis. This test Common symptoms of asthma include: can detect narrowing (obstruction) in the airways. A normal breathing test result does not mean you do not have ■ Cough—often dry and can have harsh bursts asthma. Your healthcare provider may recommend other ■ Wheezing—a whistling sound mainly when you breathe types of testing to look for asthma. For more information out through narrowed airways about pulmonary function testing, see ATS Patient ■ Chest tightness Information series at www.thoracic.org/patients. ■ Shortness of breath which may occur with activity or If you have been diagnosed with asthma, but it is not even at rest getting better with treatment, you might benefit from When you are having a problem with asthma, you may feel CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP seeing an asthma specialist. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis and Severe Asthma with Fungal Sensitisation

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis and Severe Asthma with Fungal Sensitisation Dr Rohit Bazaz National Aspergillosis Centre, UK Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust/University of Manchester ~ ABPA -a41'1 Severe asthma wl'th funga I Siens itisat i on Subacute IA Chronic pulmonary aspergillosjs Simp 1Ie a:spe rgmoma As r§i · bronchitis I ram une dysfu net Ion Lun· damage Immu11e hypce ractivitv Figure 1 In t@rarctfo n of Aspergillus Vliith host. ABP A, aHerg tc broncho pu~ mo na my as µe rgi ~fos lis; IA, i nvas we as ?@rgiH os 5. MANCHl·.'>I ER J:-\2 I Kosmidis, Denning . Thorax 2015;70:270–277. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206291 Allergic Fungal Airway Disease Phenotypes I[ Asthma AAFS SAFS ABPA-S AAFS-asthma associated with fu ngaIsensitization SAFS-severe asthma with funga l sensitization ABPA-S-seropositive a llergic bronchopulmonary aspergi ll osis AB PA-CB-all ergic bronchopulmonary aspergi ll osis with central bronchiectasis Agarwal R, CurrAlfergy Asthma Rep 2011;11:403 Woolnough K et a l, Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21:39 9 Stanford Lucile Packard ~ Children's. Health Children's. Hospital CJ Scanford l MEDICINE Stanford MANCHl·.'>I ER J:-\2 I Aspergi 11 us Sensitisation • Skin testing/specific lgE • Surface hydroph,obins - RodA • 30% of patients with asthma • 13% p.atients with COPD • 65% patients with CF MANCHl·.'>I ER J:-\2 I Alternar1a• ABPA •· .ABPA is an exagg·erated response ofthe imm1une system1 to AspergUlus • Com1pUcatio n of asthm1a and cystic f ibrosis (rarell·y TH2 driven COPD o r no identif ied p1 rior resp1 iratory d isease) • ABPA as a comp1 Ucation of asth ma affects around 2.5% of adullts. -

Diseases of the Respiratory System (J00-J99) ICD-10-CM

Diseases of the Respiratory System (J00-J99) ICD-10-CM Coverage provided by Amerigroup Inc. This publication contains proprietary information. This material is for informational purposes only. Reference the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for more information on Risk Adjustment and the CMS-HCC Model. Redistribution or other use is strictly forbidden This publication is for informational purposes only and is not guaranteed to be without defect. Please reference the current version(s) of the ICD-10-CM codebook, CMS-HCC Risk Adjustment Model, and AHA Coding Clinic for complete code sets and official coding guidance. AGPCARE-0080-19 63321MUPENABS 10/05/16 Diseases of the respiratory system are located in chapter Intermittent asthma which is defined as less 10 of the ICD-10-CM code book; this chapter includes than or equal to two occurrences per week. conditions such as asthma, pneumonia, and chronic Persistent asthma which includes three levels obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). of severity: Mild: more than two times per week Reporting respiratory conditions Moderate: daily and may restrict Codes for reporting diseases of the respiratory physical activity system in ICD-10-CM feature relatively minor Severe: throughout the day with changes from ICD-9-CM. Most of the changes recurrent severe attacks limiting the involve understanding the medical terminology that ability to breathe the more specific codes include, as well as, the new The fourth character indicates severity, and the general coding structure and rules. fifth identifies whether status asthmaticus or At the beginning of chapter 10 for “Diseases of exacerbation is present. the Respiratory System (J00-J99),” an instructional note states, “When a respiratory condition is Asthma ICD-10-CM description described as occurring in more than one site and Category J45 Asthma is not specifically indexed, it should be classified Includes: to the lower anatomic site.” For example, Allergic: tracheobronchitis is classified to bronchitis with Asthma code J40. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis: a Perplexing Clinical Entity Ashok Shah,1* Chandramani Panjabi2

Review Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2016 July;8(4):282-297. http://dx.doi.org/10.4168/aair.2016.8.4.282 pISSN 2092-7355 • eISSN 2092-7363 Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis: A Perplexing Clinical Entity Ashok Shah,1* Chandramani Panjabi2 1Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Delhi, India 2Department of Respiratory Medicine, Mata Chanan Devi Hospital, New Delhi, India This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In susceptible individuals, inhalation of Aspergillus spores can affect the respiratory tract in many ways. These spores get trapped in the viscid spu- tum of asthmatic subjects which triggers a cascade of inflammatory reactions that can result in Aspergillus-induced asthma, allergic bronchopulmo- nary aspergillosis (ABPA), and allergic Aspergillus sinusitis (AAS). An immunologically mediated disease, ABPA, occurs predominantly in patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis (CF). A set of criteria, which is still evolving, is required for diagnosis. Imaging plays a compelling role in the diagno- sis and monitoring of the disease. Demonstration of central bronchiectasis with normal tapering bronchi is still considered pathognomonic in pa- tients without CF. Elevated serum IgE levels and Aspergillus-specific IgE and/or IgG are also vital for the diagnosis. Mucoid impaction occurring in the paranasal sinuses results in AAS, which also requires a set of diagnostic criteria. Demonstration of fungal elements in sinus material is the hall- mark of AAS. -

Right Heart Pressures in Bronchial Asthma

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.26.1.39 on 1 January 1971. Downloaded from Thorax (1971), 26, 39. Right heart pressures in bronchial asthma R. F. GUNSTONE St. George's Hospital, London S.W.1 Right heart pressures, electrocardiograms, blood gases, and peak expiratory flow rates were measured in nine patients admitted to hospital with severe bronchial asthma. Low or normal right heart pressures were found despite electrocardiographic changes in five patients consisting of right atrial P waves, abnormal right axis deviation, and in one patient T-wave changes in pre- cordial leads. These electrocardiographic changes reverted towards normal on recovery of the patient from the asthmatic attack. Electrocardiographic changes suggestive of right The procedure was carried out in the general ward heart embarrassment have been noted in acute with the patient in the sitting position supported at 60 bronchial asthma, particularly right atrial P waves to 90 degrees to the horizontal because orthopnoea (P and abnormal right axis deviation was always present. Immediately after catheterization pulmonale) the peak expiratory flow rate was measured with a (Harkavy and Romanoff, 1942; Miyamato, Wright peak flow meter (Wright and McKerrow, Bastaroli, and Hoffman, 1961; Ambiavagar, 1959) and blood (capillary or arterial) was taken for Jones and Roberts, 1967). These observations measurement of pH, Pco2, and standard bicarbonate raise the possibility that death in bronchial asthma by the Astrup method (Astrup, J0rgensen, Andersen, may be due to acute cor pulmonale although and Engel, 1960). The peak flow rate and electro- copyright. necropsy evidence is against this suggestion (Earle, cardiogram were repeated after recovery. -

So You Have Asthma

So You Have Asthma A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES So You Have Asthma A GUIDE FOR PATIENTS AND THEIR FAMILIES NIH Publication No. 13-5248 Originally Printed 2007 Revised March 2013 Contents Overview ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................3 Asthma—Some Basics ................................................................................................................................4 Why You? .........................................................................................................................................................6 How Does Asthma Make You Feel? ......................................................................................................8 How Do You Know if You Have Asthma? ...........................................................................................9 How To Control Your Asthma ................................................................................................................ 11 Your Asthma Management Partnership ................................................................................... 11 Your Written Asthma Action Plan ............................................................................................. 12 Your Asthma Medicines: How They Work and How To Take Them .......................... -

2020 GINA Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention

POCKET GUIDE FOR ASTHMA MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION (for Adults and Children Older than 5 Years) DISTRIBUTE OR COPY NOT DO MATERIAL- COPYRIGHTED A Pocket Guide for Health Professionals Updated 2020 BASED ON THE GLOBAL STRATEGY FOR ASTHMA MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION © 2020 Global Initiative for Asthma GLOBAL INITIATIVE FOR ASTHMA ASTHMA MANAGEMENT AND PREVENTION DISTRIBUTE for adults and children older ORthan 5 years COPY NOT A POCKET GUIDE FOR HEALTHDO PROFESSIONALS MATERIAL-Updated 2020 GINA Science Committee Chair: Helen Reddel, MBBS PhD COPYRIGHTED GINA Board of Directors Chair: Louis-Philippe Boulet, MD GINA Dissemination and Implementation Committee Chair: Mark Levy, MD (to Sept 2019); Alvaro Cruz, MD (from Sept 2019) GINA Assembly The GINA Assembly includes members from many countries, listed on the GINA website www.ginasthma.org. GINA Executive Director Rebecca Decker, BS, MSJ Names of members of the GINA Committees are listed on page 48. 1 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BDP Beclometasone dipropionate COPD Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease CXR Chest X-ray DPI Dry powder inhaler FeNO Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide FEV1 Forced expiratory volume in 1 second FVC Forced vital capacity GERD Gastroesophageal reflux disease HDM House dust mite ICS Inhaled corticosteroids ICS-LABA Combination ICS and LABA Ig Immunoglobulin IL Interleukin DISTRIBUTE IV Intravenous OR LABA Long-acting beta2-agonist COPY LAMA Long-acting muscarinic antagonist NOT LTRA Leukotriene receptor antagonistDO n.a. Not applicable NSAID Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug MATERIAL- O2 Oxygen OCS Oral corticosteroids PEF Peak expiratory flow pMDI PressurizedCOPYRIGHTED metered dose inhaler SABA Short-acting beta2-agonist SC Subcutaneous SLIT Sublingual immunotherapy 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations ........................................................................................ -

Asthma and COVID-19: Scientific Brief

Asthma and COVID-19 Scientific brief 19 April 2021 Background People with asthma (PWA) generally are considered at higher risk from respiratory infections, as is seen annually with influenza. At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, PWA were widely assumed to be at increased risk from COVID-19. However, as data emerged throughout 2020, the association between asthma and COVID-19 appeared less clear (1). A rapid systematic review was undertaken to inform this scientific brief. The review set out to assess the available peer-reviewed literature regarding whether PWA are at increased risk of infection with the virus that causes COVID-19, and/or of experiencing complications or death. In particular, the review set out to analyse evidence on the following questions. • Is asthma associated with increased risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 disease? • Is asthma associated with hospitalization with COVID-19? • Is asthma associated with the severity of COVID-19 outcomes? Methods A protocol for the rapid review was documented in advance of evidence retrieval and data analysis. Searches included the Cochrane COVID-19 study register, Embase, MEDLINE and LitCOVID on 8 October 2020 for published literature or literature accepted for publication but not yet published, in any language. Two reviewers screened titles and abstracts, and full texts of selected references, according to the following inclusion criteria: • population: people diagnosed with asthma, with no limitations by age, disease severity or duration • exposure: SARS-CoV-2 infection • comparator: people without asthma • outcome: rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: confirmed/suspected infection; hospitalization; admission to intensive care unit (ICU); death. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis in a Patient with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Prim Care Respir J 2012; 21(1): 111-114 CASE-BASED LEARNING Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Elias Mira,*Ashok Shaha a Department of Respiratory Medicine, Vallabhbhai Patel Chest Institute, University of Delhi, Delhi, India Originally received 13th April 2011; resubmitted 27th July 2011; revised 16th September 2011; accepted 17th September 2011; online 5th January 2012 Summary Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is a debilitating lung disease which occurs as a result of interplay between a variety of host and environmental factors. It occurs in certain susceptible individuals who develop hypersensensitivity to the colonised Aspergillus species. ABPA is a complicating factor in 2% of patients with asthma and is also seen in patients with cystic fibrosis. Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are known to share key elements of pathogenesis. It is well known that ABPA can occur in patients with asthma, but it has recently been reported in patients with COPD as well. We report a 55-year-old male ex-smoker who presented with complaints of exertional breathlessness and productive cough for five years and an episode of haemoptysis four days prior to presentation. Spirometery showed airflow obstruction which was not reversible with bronchodilators. Chest CT scan revealed paraseptal emphysema along with central bronchiectasis (CB) in the right upper lobe and bilateral lower lobes. A type I skin hypersensitivity reaction to Aspergillus species was elicited. He fulfilled the serological criteria for ABPA and was diagnosed as having concomitant COPD and ABPA-CB. The patient was initiated on therapy for COPD along with oral corticosteroids, on which he had remarkable symptomatic improvement. -

Environmental Management of Pediatric Asthma Guidelines for Health Care Providers

Environmental Management of Pediatric Asthma Guidelines for Health Care Providers National Environmental Education Foundation Health & Environment AN ,vi Knowledge to live by Endorsed by Ambulatory Pediatric Association, American Association of Colleges of Nursing, Association of Faculties of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners Supported by American Academy of Pediatrics and National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners Environmental Management of Pediatric Asthma Guidelines for Health Care Providers August 2005 Health & Environment A National Environmental Education Foundation Program The National Environmental Education Foundation 4301 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 160 Washington, DC 20008 Tel: 202-833-2933 Fax: 202-261-6464 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.neefusa.org/health.htm This project was made possible through a grant from ... NIEHS -._,~f National Institute of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. #p' • Environmental Health Sciences Additional funding was provided by American Legion Child Welfare Foundation sponsored by Pediatric Asthma Initiative Steering Committee n James Roberts, MD, MPH, (Chair) Medical University of South Carolina; Representative, American Academy of Pediatrics n Elizabeth Blackburn, RN, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Children’s Health Protection n Allen Dearry, PhD, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences n Peyton Eggleston, MD, Johns Hopkins University, School of Medicine n Ruth Etzel, MD, PhD, George Washington University, School of Public Health & Health Services n Joel Forman, MD, Mount Sinai Medical Center n Jackie Goeldner, MPH, Kaiser Permanente n Robert Johnson, MD, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry n Philip Landrigan, MD, MSc, Mount Sinai School of Medicine n Leyla Erk McCurdy, MPhil, The National Environmental Education Foundation n Stephen Redd, MD, National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention n Richard M.