Diagnosing Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caring for Children with Special Needs ALLERGIES and ASTHMA

caring for children with special needs ALLERGIES AND ASTHMA We don’t usually think of children with allergies or asthma as children with “special needs,” but they certainly are. In fact, children with these conditions are probably the most frequently encountered “special needs” children. Child care providers can do a great deal to help individual children manage their specific allergy or asthma needs and feel more comfortable in a child care setting. Allergies wastes. Every house has them, no matter how clean. Other inhaled Children with allergies face the allergens include mold, pollen (hay same social difficulties as do adults, fever), animal dander (especially but they have less maturity and from cats), chemicals, and per emotional resources to deal with fumes. them. Children find that they cannot eat what their friends eat or The most common allergy symp cannot play outside during some toms are seasons. Until a child is mature � a clear, runny nose and enough to understand why she sneezing, cannot do something, you must be � itchy or stuffed-up nose or careful to help the child through the itchy, runny eyes, and difficulties. Start teaching a child early on about what he is allergic to; � asthma (remember that not all you will not always be able to people with asthma have monitor everything. allergies and not all allergies Some foods can cause a life cause or develop into asthma). threatening reaction. The mouth, throat, and bronchial tubes swell enough to interfere with breathing. Strategies for inclusion The person may wheeze or faint. Some parents have found that by Often there are generalized hives volunteering to bring food to and/or a swollen face. -

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis Revealing Asthma

CASE REPORT published: 22 June 2021 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.695954 Case Report: Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis Revealing Asthma Houda Snen 1,2*, Aicha Kallel 2,3*, Hana Blibech 1,2, Sana Jemel 2,3, Nozha Ben Salah 1,2, Sonia Marouen 3, Nadia Mehiri 1,2, Slah Belhaj 3, Bechir Louzir 1,2 and Kalthoum Kallel 2,3 1 Pulmonary Department, Hospital Mongi Slim, La Marsa, Tunisia, 2 Faculty of Medicine, Tunis El Manar University, Tunis, Tunisia, 3 Parasitology and Mycology Department, La Rabta Hospital, Tunis, Tunisia Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) is an immunological pulmonary disorder caused by hypersensitivity to Aspergillus which colonizes the airways of patients with asthma and cystic fibrosis. Its diagnosis could be difficult in some cases due to atypical Edited by: presentations especially when there is no medical history of asthma. Treatment of ABPA is Brian Stephen Eley, frequently associated to side effects but cumulated drug toxicity due to different molecules University of Cape Town, South Africa is rarely reported. An accurate choice among the different available molecules and Reviewed by: effective on ABPA is crucial. We report a case of ABPA in a woman without a known Shivank Singh, Southern Medical University, China history of asthma. She presented an acute bronchitis with wheezing dyspnea leading to an Richard B. Moss, acute respiratory failure. She was hospitalized in the intensive care unit. The Stanford University, United States bronchoscopy revealed a complete obstruction of the left primary bronchus by a sticky *Correspondence: Houda Snen greenish material. The culture of this material isolated Aspergillus fumigatus and that of [email protected] bronchial aspiration fluid isolated Pseudomonas aeruginosa. -

Symptoms Related to Asthma and Chronic Bronchitis in Three Areas of Sweden

Eur Respir J, 1994, 7, 2146–2153 Copyright ERS Journals Ltd 1994 DOI: 10.1183/09031936.94.07122146 European Respiratory Journal Printed in UK - all rights reserved ISSN 0903 - 1936 Symptoms related to asthma and chronic bronchitis in three areas of Sweden E. Björnsson*, P. Plaschke**, E. Norrman+, C. Janson*, B. Lundbäck+, A. Rosenhall+, N. Lindholm**, L. Rosenhall+, E. Berglund++, G. Boman* Symptoms related to asthma and chronic bronchitis in three areas of Sweden. E. Björnsson, *Dept of Lung Medicine and Asthma P. Plaschke, E. Norrman, C. Janson, B. Lundbäck, A. Rosenhall, N. Lindholm, L. Research Center, Akademiska sjukhu- Rosenhall, E. Berglund, G. Boman. ERS Journals Ltd 1994. set, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. ABSTRACT: Does the prevalence of respiratory symptoms differ between regions? **Asthma and Allergy Research Center, Sahlgren's Hospital, University of Göteborg, As a part of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey, we present data Göteborg, Sweden. +Dept of Pulmonary from an international questionnaire on asthma symptoms occurring during a 12 Medicine and Allergology, Univer- month period, smoking and symptoms of chronic bronchitis. The questionnaire was sity Hospital of Northern Sweden, Umeå, mailed to 10,800 persons aged 20–44 yrs living in three regions of Sweden (Västerbotten, Sweden. ++Dept of Pulmonary Medicine, Uppsala and Göteborg) with different environmental characteristics. The total Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, response rate was 86%. Sweden. Wheezing was reported by 20.5%, and the combination of wheezing without a Correspondence: E. Björnsson, Dept of cold and wheezing with breathlessness by 7.4%. The use of asthma medication was Lung Medicine, Akademiska sjukhuset, S- reported by 5.3%. -

Rapid and Precise Diagnosis of Pneumonia Coinfected By

Rapid and precise diagnosis of pneumonia coinfected by Pneumocystis jirovecii and Aspergillus fumigatus assisted by next-generation sequencing in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report Yili Chen Sun Yat-Sen University Lu Ai Sun Yat-Sen University Yingqun Zhou First Peoples Hospital of Nanning Yating Zhao Sun Yat-Sen University Jianyu Huang Sun Yat-Sen University Wen Tang Sun Yat-Sen University Yujian Liang ( [email protected] ) Sun Yat-Sen University Case report Keywords: Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus fumigatus, Next generation sequencing, Case report Posted Date: March 19th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-154016/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/12 Abstract Background: Pneumocystis jirovecii and Aspergillus fumigatus, are opportunistic pathogenic fungus that has a major impact on mortality in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. With the potential to invade multiple organs, early and accurate diagnosis is essential to the survival of SLE patients, establishing an early diagnosis of the infection, especially coinfection by Pneumocystis jirovecii and Aspergillus fumigatus, still remains a great challenge. Case presentation: In this case, we reported that the application of next -generation sequencing in diagnosing Pneumocystis jirovecii and Aspergillus fumigatus coinfection in a Chinese girl with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Voriconazole was used to treat pulmonary aspergillosis, besides sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim (SMZ-TMP), and caspofungin acetate to treat Pneumocystis jirovecii infection for 6 days. On Day 10 of admission, her chest radiograph displayed obvious absorption of bilateral lung inammation though the circumstance of repeated fever had not improved. -

Central Nervous System Infections by Members of the Pseudallescheria

Review article Central nervous system infections by members of the Pseudallescheria boydii species complex in healthy and immunocompromised hosts: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and outcome A. Serda Kantarcioglu,1 Josep Guarro2 and G. S. de Hoog3 1Department of Microbiology and Clinical Microbiology, Cerrahpasa Medical Faculty, Istanbul, Turkey, 2Unitat de Microbiologia, Facultat de Medicina i Ciencies de la Salut, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain and 3Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, and Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Summary Infections caused by members of the Pseudallescheria boydii species complex are currently among the most common mould infections. These fungi show a particular tropism for the central nervous system (CNS). We reviewed all the available reports on CNS infections, focusing on the geographical distribution, infection routes, immunity status of infected individuals, type and location of infections, clinical manifestations, treatment and outcome. A total of 99 case reports were identified, with similar percentage of healthy and immunocompromised patients (44% vs. 56%; P = 0.26). Main clinical types were brain abscess (69%), co-infection of brain tissue and ⁄ or spinal cord with meninges (10%) and meningitis (9%). The mortality rate was 74%, regardless of the patientÕs immune status, or the infection type and ⁄ or location. Cerebrospinal fluid culture was revealed as a not very important tool as the percentage of positive samples for P. boydii complex was not different from that of negative ones (67% vs. 33%; P = 0.10). In immunocompetent patients, CNS infection was preceded by near drowning or trauma. In these patients, the infection was characterised by localised involvement and a high fatality rate (76%). -

Rhinitis and Sinusitis

Glendale Animal Hospital 623-934-7243 www.familyvet.com Rhinitis and Sinusitis (Inflammation of the Nose and Sinuses) Basics OVERVIEW Rhinitis—inflammation of the lining of the nose Sinusitis—inflammation of the sinuses The nasal cavity communicates directly with the sinuses; thus inflammation of the nose (rhinitis) and inflammation of the sinuses (sinusitis) often occur together (known as “rhinosinusitis”) “Upper respiratory tract” (also known as the “upper airways”) includes the nose, nasal passages, throat (pharynx), and windpipe (trachea) “Lower respiratory tract” (also known as the “lower airways”) includes the bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli (the terminal portion of the airways, in which oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged) SIGNALMENT/DESCRIPTION OF PET Species Dogs Cats Breed Predilections Short-nosed, flat-faced (known as “brachycephalic”) cats are more prone to long-term (chronic) inflammation of the nose (rhinitis), and possibly fungal rhinitis Dogs with a long head and nose (known as “dolichocephalic dogs,” such as the collie and Afghan hound) are more prone to Aspergillus (a type of fungus) infection and nasal tumors Mean Age and Range Cats—sudden (acute) viral inflammation of the nose and sinuses (rhinosinusitis) and red masses in the nasal cavity and throat (known as “nasopharyngeal polyps”) are more common in young kittens (6–12 weeks of age) Congenital (present at birth) diseases (such as cleft palate) are more common in young pets Tumors/cancer and dental disease—are more common in older pets Foreign -

Immunopathology of Aspergillus Infections in Children with Chronic Granulomatous Disease and Cystic Fibrosis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aberdeen University Research Archive Immunopathology of Aspergillus Infections in Children with Chronic Granulomatous Disease and Cystic Fibrosis. Adilia Warris, MD PhD MRC Centre for Medical Mycology, Aberdeen Fungal Group, Institute of Medical Sciences, University of Aberdeen, UK. Corresponding address: Medical Research Council Centre for Medical Mycology at the University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen Fungal Group, Institute of Medical Sciences, Foresterhill, AB25 2ZD, Aberdeen, UK. Phone: +44 (0)1224437596. Fax: +44 (0)1224437506. E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements AW is supported by the Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (grant 097377) and the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology (grant MR/N006364/1) at the University of Aberdeen. Key Words: chronic granulomatous disease, cystic fibrosis, Aspergillus, aspergillosis, inflammation Abbreviated title: Aspergillus infections in CGD and CF Running head title: Aspergillus infections in CGD and CF Introduction Children with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) and cystic fibrosis (CF) share some important clinical characteristics which are the consequence of their intrinsic susceptibility to recurrent and opportunistic infections and exaggerated inflammation. Although the clinical phenotypes of Aspergillus disease differ substantially between those two non-neutropenic patient groups, the underlying pathophysiology show remarkable commonalities with excessive inflammation being a hallmark of Aspergillus disease. The occurrence of Aspergillus infections in these two patient populations is associated with decreased quality of life and premature death. Our knowledge of the pathophysiology of Aspergillus infections is mainly derived from infections caused by a single species - Aspergillus fumigatus - in the neutropenic host. The insights obtained in this setting do not translate well to the non-neutropenic host. -

Rhinotillexomania in a Cystic Fibrosis Patient Resulting in Septal Perforation Mark Gelpi1*, Emily N Ahadizadeh1,2, Brian D’Anzaa1 and Kenneth Rodriguez1

ISSN: 2572-4193 Gelpi et al. J Otolaryngol Rhinol 2018, 4:036 DOI: 10.23937/2572-4193.1510036 Volume 4 | Issue 1 Journal of Open Access Otolaryngology and Rhinology CASE REPORT Rhinotillexomania in a Cystic Fibrosis Patient Resulting in Septal Perforation Mark Gelpi1*, Emily N Ahadizadeh1,2, Brian D’Anzaa1 and Kenneth Rodriguez1 1 Check for University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, USA updates 2Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, USA *Corresponding author: Mark Gelpi, MD, University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, 11100 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA, Tel: (216)-844-8433, Fax: (216)-201-4479, E-mail: [email protected] paranasal sinuses [1,4]. Nasal symptoms in CF patients Abstract occur early, manifesting between 5-14 years of age, and Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a multisystem disease that can have represent a life-long problem in this population [5]. Pa- significant sinonasal manifestations. Viscous secretions are one of several factors in CF that result in chronic sinona- tients with CF can develop thick nasal secretions con- sal pathology, such as sinusitis, polyposis, congestion, and tributing to chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), nasal conges- obstructive crusting. Persistent discomfort and nasal man- tion, nasal polyposis, headaches, and hyposmia [6-8]. ifestations of this disease significantly affect quality of life. Sinonasal symptoms of CF are managed medically with Digital manipulation and removal of crusting by the patient in an attempt to alleviate the discomfort can have unfore- topical agents and antibiotics, however surgery can be seen damaging consequences. We present one such case warranted due to the chronic and refractory nature of and investigate other cases of septal damage secondary to the symptoms, with 20-25% of CF patients undergoing digital trauma, as well as discuss the importance of sinona- sinus surgery in their lifetime [8]. -

FINAL RISK ASSESSMENT for Aspergillus Niger (February 1997)

ATTACHMENT I--FINAL RISK ASSESSMENT FOR Aspergillus niger (February 1997) I. INTRODUCTION Aspergillus niger is a member of the genus Aspergillus which includes a set of fungi that are generally considered asexual, although perfect forms (forms that reproduce sexually) have been found. Aspergilli are ubiquitous in nature. They are geographically widely distributed, and have been observed in a broad range of habitats because they can colonize a wide variety of substrates. A. niger is commonly found as a saprophyte growing on dead leaves, stored grain, compost piles, and other decaying vegetation. The spores are widespread, and are often associated with organic materials and soil. History of Commercial Use and Products Subject to TSCA Jurisdiction The primary uses of A. niger are for the production of enzymes and organic acids by fermentation. While the foods, for which some of the enzymes may be used in preparation, are not subject to TSCA, these enzymes may have multiple uses, many of which are not regulated except under TSCA. Fermentations to produce these enzymes may be carried out in vessels as large as 100,000 liters (Finkelstein et al., 1989). A. niger is also used to produce organic acids such as citric acid and gluconic acid. The history of safe use for A. niger comes primarily from its use in the food industry for the production of many enzymes such as a-amylase, amyloglucosidase, cellulases, lactase, invertase, pectinases, and acid proteases (Bennett, 1985a; Ward, 1989). In addition, the annual production of citric acid by fermentation is now approximately 350,000 tons, using either A. -

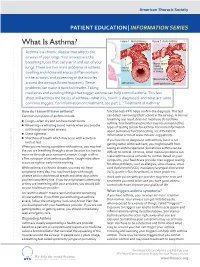

What Is Asthma? Figure 1

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES What Is Asthma? Figure 1. Normal Airway Figure 2. Acute Asthma Asthma is a chronic disease that affects the airways of your lungs. Your airways are the breathing tubes that carry air in and out of your Muscle spasm causing lungs. There are two main problems in asthma: relaxed narrowing muscles swelling and increased mucus (inflammation) of airways in the airways, and squeezing of the muscles Mucus build up around the airways (bronchospasm). These open airways Swelling/inammation problems can make it hard to breathe. Taking medicines and avoiding things that trigger asthma can help control asthma. This fact sheet will address the basics of asthma—what it is, how it is diagnosed, and what are some common triggers. For information on treatment, see part 2, “Treatment of Asthma”. How do I know if I have asthma? function test–PFT) helps confirm the diagnosis. This test Common symptoms of asthma include: can detect narrowing (obstruction) in the airways. A normal breathing test result does not mean you do not have ■ Cough—often dry and can have harsh bursts asthma. Your healthcare provider may recommend other ■ Wheezing—a whistling sound mainly when you breathe types of testing to look for asthma. For more information out through narrowed airways about pulmonary function testing, see ATS Patient ■ Chest tightness Information series at www.thoracic.org/patients. ■ Shortness of breath which may occur with activity or If you have been diagnosed with asthma, but it is not even at rest getting better with treatment, you might benefit from When you are having a problem with asthma, you may feel CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP seeing an asthma specialist. -

Cryptogenic Organizing Pneumonia—Results of Treatment with Clarithromycin Versus Corticosteroids—Observational Study

RESEARCH ARTICLE Cryptogenic organizing pneumoniaÐResults of treatment with clarithromycin versus corticosteroidsÐObservational study Elżbieta Radzikowska1*, Elżbieta Wiatr1☯, Renata Langfort2³, Iwona Bestry3³, Agnieszka Skoczylas4, Ewa Szczepulska-Wo jcik2³, Dariusz Gawryluk1☯, Piotr Rudziński5³, Joanna Chorostowska-Wynimko6³, Kazimierz Roszkowski-Śliż1³ 1 III Department of Lung Disease National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 2 Pathology Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 3 Radiology Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, a1111111111 Poland, 4 Geriatrics Department National Institute of Geriatrics, Rheumatology and Rehabilitation, Warsaw, a1111111111 Poland, 5 Thoracic Surgery Department National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, a1111111111 Warsaw, Poland, 6 Laboratory of Molecular Diagnostics and Immunology National Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases Research Institute, Warsaw, Poland a1111111111 a1111111111 ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. ³ These authors also contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Radzikowska E, Wiatr E, Langfort R, Bestry I, Skoczylas A, Szczepulska-WoÂjcik E, et al. (2017) Cryptogenic organizing pneumoniaÐ Background Results of treatment with clarithromycin versus Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) is a clinicopathological syndrome of unknown ori- corticosteroidsÐObservational study. PLoS ONE 12(9): e0184739. -

Does Cystic Fibrosis Constitute an Advantage in COVID-19 Infection? Valentino Bezzerri, Francesca Lucca, Sonia Volpi and Marco Cipolli*

Bezzerri et al. Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2020) 46:143 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-020-00909-1 LETTER TO THE EDITOR Open Access Does cystic fibrosis constitute an advantage in COVID-19 infection? Valentino Bezzerri, Francesca Lucca, Sonia Volpi and Marco Cipolli* Abstract The Veneto region is one of the most affected Italian regions by COVID-19. Chronic lung diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), may constitute a risk factor in COVID-19. Moreover, respiratory viruses were generally associated with severe pulmonary impairment in cystic fibrosis (CF). We would have therefore expected numerous cases of severe COVID-19 among the CF population. Surprisingly, we found that CF patients were significantly protected against infection by SARS-CoV-2. We discussed this aspect formulating some reasonable theories. Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, SARS-CoV-2, Covid-19, Azythromycin, DNase Introduction status, one would surmise that CF patients would be at The comorbidities of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, an increased risk of developing severe COVID-19 illness. heart failure, and chronic lung disease have been associ- ated with poor outcome in coronavirus disease 2019 Methods (COVID-19) [1]. Once Severe Acute Respiratory Syn- We conducted a retrospective study of 532 CF patients – drome (SARS) Coronavirus (CoV)-2 has infected host followed at the Cystic Fibrosis Center of Verona, Italy. cells, excessive inflammatory and thrombotic processes SARS-CoV-2 positivity was tested by collecting com- take place. A cytokine storm release with markedly ele- bined nose-throat swabs and subsequent Real-Time PCR vated IL-6 levels are associated with increased lethality using the Nimbus MuDT tm (Seegene, Seoul, South [2].