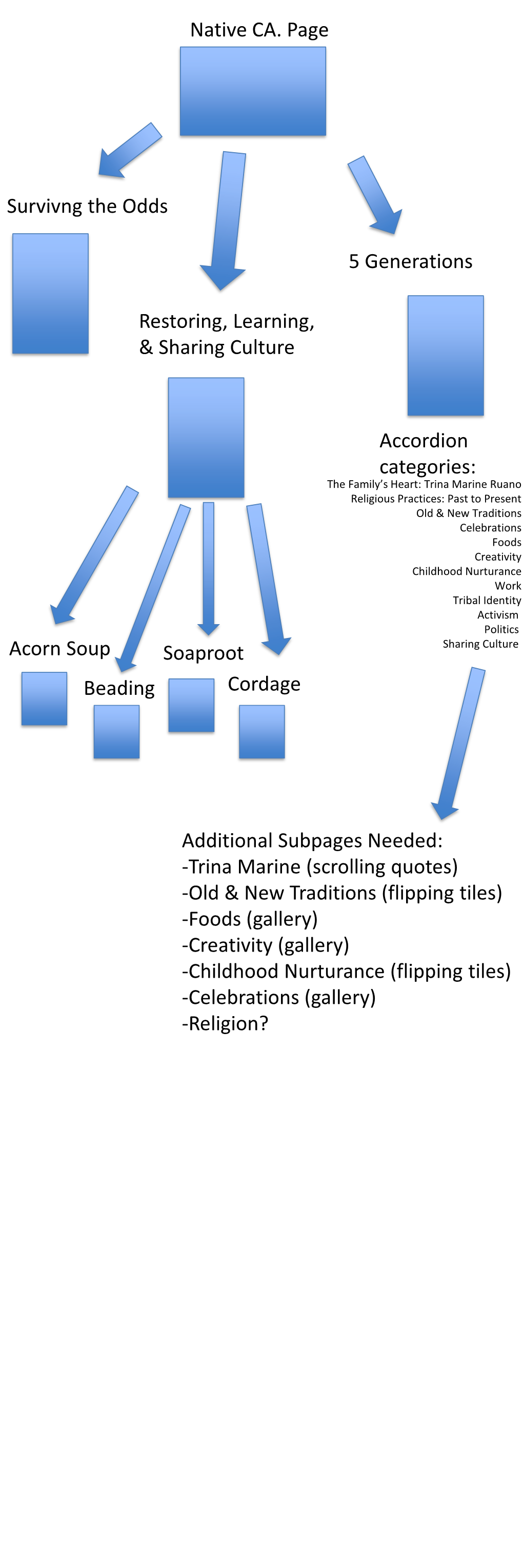

Native CA. Page Survivng the Odds 5 Generations Restoring, Learning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

An Overview of Ohlone Culture by Robert Cartier

An Overview of Ohlone Culture By Robert Cartier In the 16th century, (prior to the arrival of the Spaniards), over 10,000 Indians lived in the central California coastal areas between Big Sur and the Golden Gate of San Francisco Bay. This group of Indians consisted of approximately forty different tribelets ranging in size from 100–250 members, and was scattered throughout the various ecological regions of the greater Bay Area (Kroeber, 1953). They did not consider themselves to be a part of a larger tribe, as did well- known Native American groups such as the Hopi, Navaho, or Cheyenne, but instead functioned independently of one another. Each group had a separate, distinctive name and its own leader, territory, and customs. Some tribelets were affiliated with neighbors, but only through common boundaries, inter-tribal marriage, trade, and general linguistic affinities. (Margolin, 1978). When the Spaniards and other explorers arrived, they were amazed at the variety and diversity of the tribes and languages that covered such a small area. In an attempt to classify these Indians into a large, encompassing group, they referred to the Bay Area Indians as "Costenos," meaning "coastal people." The name eventually changed to "Coastanoan" (Margolin, 1978). The Native American Indians of this area were referred to by this name for hundreds of years until descendants chose to call themselves Ohlones (origination uncertain). Utilizing hunting and gathering technology, the Ohlone relied on the relatively substantial supply of natural plant and animal life in the local environment. With the exception of the dog, we know of no plants or animals domesticated by the Ohlone. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

Ethnohistory and Ethnogeography of the Coast Miwok and Their Neighbors, 1783-1840

ETHNOHISTORY AND ETHNOGEOGRAPHY OF THE COAST MIWOK AND THEIR NEIGHBORS, 1783-1840 by Randall Milliken Technical Paper presented to: National Park Service, Golden Gate NRA Cultural Resources and Museum Management Division Building 101, Fort Mason San Francisco, California Prepared by: Archaeological/Historical Consultants 609 Aileen Street Oakland, California 94609 June 2009 MANAGEMENT SUMMARY This report documents the locations of Spanish-contact period Coast Miwok regional and local communities in lands of present Marin and Sonoma counties, California. Furthermore, it documents previously unavailable information about those Coast Miwok communities as they struggled to survive and reform themselves within the context of the Franciscan missions between 1783 and 1840. Supplementary information is provided about neighboring Southern Pomo-speaking communities to the north during the same time period. The staff of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area (GGNRA) commissioned this study of the early native people of the Marin Peninsula upon recommendation from the report’s author. He had found that he was amassing a large amount of new information about the early Coast Miwoks at Mission Dolores in San Francisco while he was conducting a GGNRA-funded study of the Ramaytush Ohlone-speaking peoples of the San Francisco Peninsula. The original scope of work for this study called for the analysis and synthesis of sources identifying the Coast Miwok tribal communities that inhabited GGNRA parklands in Marin County prior to Spanish colonization. In addition, it asked for the documentation of cultural ties between those earlier native people and the members of the present-day community of Coast Miwok. The geographic area studied here reaches far to the north of GGNRA lands on the Marin Peninsula to encompass all lands inhabited by Coast Miwoks, as well as lands inhabited by Pomos who intermarried with them at Mission San Rafael. -

On the Ethnolinguistic Identity of the Napa Tribe: the Implications of Chief Constancio Occaye's Narratives As Recorded by Lorenzo G

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title On the Ethnolinguistic Identity of the Napa Tribe: The Implications of Chief Constancio Occaye's Narratives as Recorded by Lorenzo G. Yates Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3k52g07t Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 26(2) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Johnson, John R Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 26, No. 2 (2006) | pp. 193-204 REPORTS On the Ethnolinguistic of foUdore, preserved by Yates, represent some of the only knovra tradhions of the Napa tribe, and are thus highly Identity of the Napa Tribe: sigiuficant for anthropologists mterested m comparative The Implications of oral hterature in Native California. Furthermore, the Chief Constancio Occaye^s native words m these myths suggest that a reappraisal of Narratives as Recorded the ethnohnguistic identhy of the Napa people may be by Lorenzo G. Yates in order. BACKGROUND JOHN R. JOHNSON Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History Lorenzo Gordin Yates (1837-1909) was an English 2559 Puesta del Sol, Santa Barbara, CA 93105 immigrant who came to the United States as a teenager. He became a dentist by profession, but bad a lifelong About 1876, Lorenzo G. Yates interviewed Constancio passion for natural history. Yates moved his famUy from Occaye, described as the last "Chief of the Napas," and Wisconsm to California in 1864 and settled m CentreviUe recorded several items of folklore from his tribe. Yates in Alameda County, which later became a district of included Constancio's recollections about the use of Fremont. -

May 29, 2020 Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez Chair, Assembly

May 29, 2020 Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez Chair, Assembly Appropriations State Capitol, Room 2114 Sacramento, California 95814 RE: AB 1968 (Ramos) The Land Acknowledgement Act of 2021 – SUPPORT Dear Chair Gonzalez: The Surfrider Foundation strongly supports AB 1968, the Tribal Land Acknowledgement Act of 2020, which recognizes the land as an expression of gratitude and appreciation to those whose homelands we reside on, and is a recognition of the original people and nations who have been living on and stewarding the land since time immemorial. AB 1968 provides a learning opportunity for individuals who may have never heard the names of the tribes that continue to live on, learn from and care for the land. The Surfrider Foundation is a non-profit grassroots organization dedicated to the protection and enjoyment of our world’s oceans, waves and beaches through a powerful network. Founded in 1984, the Surfrider Foundation now maintains over one million supporters, activists and members, with more than 170 volunteer-led chapters and student clubs in the U.S., and more than 500 victories protecting our coasts. We have more than 20 chapters in along California’s coast, in areas including the ancestral homelands of indigenous peoples including the Chumash in Malibu, known as “Humaliwu” in the Chumash language, and Rincon, the Acjachemen in Trestles, known as “Panhe” in the Acjachemen language, the Amah Mutsun in Steamer Lane, the Ohlone in Mavericks, and the Acjachemen and Tongva shared territory in Huntington Beach, known as “Lukupangma” in the Tongva and Acjachemen language. These indigenous people continue to live in these ancestral homelands today and have embraced the sport of surfing in these areas, although the clichéd imagery of surf culture fails to reflect these facts. -

California-Nevada Region

Research Guides for both historic and modern Native Communities relating to records held at the National Archives California Nevada Introduction Page Introduction Page Historic Native Communities Historic Native Communities Modern Native Communities Modern Native Communities Sample Document Beginning of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the U.S. Government and the Kahwea, San Luis Rey, and Cocomcahra Indians. Signed at the Village of Temecula, California, 1/5/1852. National Archives. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/55030733 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities California Native Communities To perform a search of more general records of California’s Native People in the National Archives Online Catalog, use Advanced Search. Enter California in the search box and 75 in the Record Group box (Bureau of Indian Affairs). There are several great resources available for general information and material for kids about the Native People of California, such as the Native Languages and National Museum of the American Indian websites. Type California into the main search box for both. Related state agencies and universities may also hold records or information about these communities. Examples might include the California State Archives, the Online Archive of California, and the University of California Santa Barbara Native American Collections. Historic California Native Communities Federally Recognized Native Communities in California (2018) Sample Document Map of Selected Site for Indian Reservation in Mendocino County, California, 7/30/1856. National Archives: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/50926106 National Archives Native Communities Research Guides. https://www.archives.gov/education/native-communities Historic California Native Communities For a map of historic language areas in California, see Native Languages. -

Hosted by the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center

Hosted by the California Indian Culture and Sovereignty Center MIIYUYAM, ‘ATAAXUM ! Greetings, People – in the language of the Luiseño. The 27th Annual California Indian Conference Planning Committee welcomes you to California State University San Marcos on the traditional homeland of the Payómkowishum, People of the West. We hope you enjoy the rich cultural experiences, motivating educational practices, and the synergy that happens when so many people are gathered for a common goal – California Indians. The theme, “California Indians Leading the Way,” illustrates the continuing value of academic disciplines in the humanities, arts and social sciences. It also defines the application of these fields in the practices of California Indians, and their colleagues, in medicine, law, film and education among others. It is not money or political influence alone that fosters tribal governments and their people. The spiritual conviction of tribal self validated through song, story, remembrance and practice is a core reality lived and taught through education, in both its traditional form and contemporary tools. Hence, our keynote speakers share with us, in the broad audience, key facts in medicine, data collecting, and educational trends to aid, thwart, or defend California Indian peoples and those who assist them. The workshops provide a more intimate setting to learn unknown facts of tribal histories and to experience the continued practices of traditional cultures and values. They give a chance to explore best practices in teaching youth. Now we might learn how to name and diminish, if not eradicate, those debilitating facts of violence, drugs, disease, and alcohol. We will also immerse ourselves in the sensory world of song, film, and art. -

Supplemental Resources

Supplemental Resources By Beverly R. Ortiz, Ph.D. © 2015 East Bay Regional Park District • www.ebparks.org Supported in part by a grant from The Vinapa Foundation for Cross-Cultural Studies Ohlone Curriculum with Bay Miwok Content and Introduction to Delta Yokuts Supplemental Resources Table of Contents Teacher Resources Native American Versus American Indian ..................................................................... 1 Ohlone Curriculum American Indian Stereotypes .......................................................................................... 3 Miner’s Lettuce and Red Ants: The Evolution of a Story .............................................. 7 A Land of Many Villages and Tribes ............................................................................. 10 Other North American Indian Groups ............................................................................ 11 A Land of Many Languages ........................................................................................... 15 Sacred Places and Narratives .......................................................................................... 18 Generations of Knowledge: Sources ............................................................................... 22 Euro-American Interactions with Plants and Animals (1800s) .......................................... 23 Staple Foods: Acorns ........................................................................................................... 28 Other Plant Foods: Cultural Context .............................................................................. -

Collaborations with Indigenous Nations, Communities, and Individuals Scott Scoggins and Erich Steinman

Unsettling Engagements: Collaborations with Indigenous Nations, Communities, and Individuals Scott Scoggins and Erich Steinman Abstract The presence of urban Indian communities and American Indian tribal nations in and near metropolitan areas creates tremendous potential for expanding campus community collaborations regarding teaching, research, and service. However, many challenges must be addressed, including acknowledging the colonial context of relations between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples in general as well as the specific role that education has played in the ongoing marginalization of American Indians. Rather than simply serving American Indian communities, academic engagement must be premised on self-scrutiny and intercultural respect that will unsettle taken-for-granted academic perspectives, logics, and procedures. Such efforts can generate deeply rewarding and valuable outcomes. Unbeknownst to some, many urban colleges and universities are located in "Indian Country." By this we don't just mean that such institutions are on land that was dispossessed from the long-time indigenous inhabitants, but rather that there are often robust pan-tribal Indian communities in the respective metropolitan areas, often with American Indian tribal nations in close proximity. In some urban areas pan-tribal communities reflect regional tribal populations, whereas in other cases, the indigenous populations are from all around the United States or from elsewhere in North America or Central America. Some of these tribal nations are federally recognized, others are state-recognized, and others are not recognized. All of these communities and nations are engaged in various types of cultural, political, and economic resurgence, as part of a dynamic wave of indigenous decolonization unfolding over the last few decades. -

33 Federally Recognized Tribes

COUNTY TRIBAL NAME (CULTURE) 1. DEL NORTE ELK VALLEY RANCHERIA OF CALIFORNIA (ATHABASCAN, TOLOWA) 2. DEL NORTE RESIGHINI RANCHERIA (YUROK) 3. DEL NORTE SMITH RIVER RANCHERIA (TOLOWA) 4. DEL NORTE YUROK TRIBE OF THE YUROK RESERVATION (YUROK) 5. HUMBOLDT BEAR RIVER BAND OF THE ROHNERVILLE RANCHERIA (MATTOLE, WIYOT) 6. HUMBOLDT BIG LAGOON RANCHERIA (TOLOWA, YUROK) 7. HUMBOLDT BLUE LAKE RANCHERIA (TOLOWA, WIYOT, YUROK) 8. HUMBOLDT CHER-AE HEIGHTS INDIAN COMMUNITY OF THE TRINIDAD RANCHERIA (MIWOK, TOLOWA, YUROK) 9. HUMBOLDT HOOPA VALLEY TRIBAL COUNCIL (HOOPA, HUPA) 10. HUMBOLDT / SISKIYOU (SHARED COUNTY KARUK TRIBE OF CALIFORNIA BORDER) (KARUK) 11. HUMBOLDT WIYOT TRIBE (WIYOT) 12. LAKE BIG VALLEY BAND OF POMO INDIANS OF THE BIG VALLEY RANCHERIA (POMO) 13. LAKE ELEM INDIAN COLONY OF POMO INDIANS OF THE SULPHUR BANK RANCHERIA (POMO) 14. LAKE UPPER LAKE BAND OF POMO INDIANS (HABEMATOLEL) (POMO) 15. LAKE MIDDLETOWN RANCHERIA OF LAKE MIWOK/POMO INDIANS (MIWOK, POMO and MIWOK-LAKE MIWOK) 16. LAKE ROBINSON RANCHERIA TRIBE OF POMO INDIANS (POMO) 17. LAKE SCOTTS VALLEY BAND OF POMO INDIANS (POMO, WAILAKI) 18. MENDOCINO CAHTO TRIBE OF THE LAYTONVILLE RANCHERIA (CAHTO, POMO) 19. MENDOCINO COYOTE VALLEY BAND OF POMO INDIANS (POMO) 20. MENDOCINO DRY CREEK RANCHERIA OF POMO INDIANS (MAHILAKAWNA, POMO) 21. MENDOCINO GUIDIVILLE RANCHERIA OF CALIFORNIA (POMO) 22. MENDOCINO HOPLAND BAND OF POMO INDIANS OF THE HOPLAND RANCHERIA (POMO, and SHANEL, SHO-KA-WAH) 23. MENDOCINO MANCHESTER-POINT ARENA BAND OF POMO INDIANS (POMO) 24. MENDOCINO PINOLEVILLE BAND OF POMO INDIANS (POMO) 25. MENDOCINO POTTER VALLEY RANCHERIA (POMO) 26. MENDOCINO REDWOOD VALLEY LITTLE RIVER BAND OF POMO INDIANS (POMO) 27.