Ohlone Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

Spring/Summer 2018

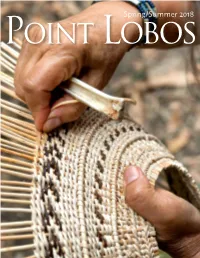

Spring/Summer 2018 Point Lobos Board of Directors Sue Addleman | Docent Administrator Kit Armstrong | President Chris Balog Jacolyn Harmer Ben Heinrich | Vice President Karen Hewitt Loren Hughes Diana Nichols Julie Oswald Ken Ruggerio Jim Rurka Joe Vargo | Secretary John Thibeau | Treasurer Cynthia Vernon California State Parks Liaison Sean James | [email protected] A team of State Parks staff, Point Lobos Docents and community volunteers take a much-needed break after Executive Director restoring coastal bluff habitat along the South Shore. Anna Patterson | [email protected] Development Coordinator President’s message 3 Tracy Gillette Ricci | [email protected] Kit Armstrong Docent Coordinator and School Group Coordinator In their footsteps 4 Melissa Gobell | [email protected] Linda Yamane Finance Specialist Shell of ages 7 Karen Cowdrey | [email protected] Rae Schwaderer ‘iim ‘aa ‘ishxenta, makk rukk 9 Point Lobos Magazine Editor Reg Henry | [email protected] Louis Trevino Native plants and their uses 13 Front Cover Chuck Bancroft Linda Yamane weaves a twined work basket of local native plant materials. This bottomless basket sits on the rim of a From the editor 15 shallow stone mortar, most often attached to the rim with tar. Reg Henry Photo: Neil Bennet. Notes from the docent log 16 Photo Spread, pages 10-11 Compiled by Ruthann Donahue Illustration of Rumsen life by Linda Yamane. Acknowledgements 18 Memorials, tributes and grants Crossword 20 Ann Pendleton Our mission is to protect and nurture Point Lobos State Natural Reserve, to educate and inspire visitors to preserve its unique natural and cultural resources, and to strengthen the network of Carmel Area State Parks. -

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A

California Indian Food and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Contributors: Ira Jacknis, Barbara Takiguchi, and Liberty Winn. Sources Consulted The former exhibition: Food in California Indian Culture at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Ortiz, Beverly, as told by Julia Parker. It Will Live Forever. Heyday Books, Berkeley, CA 1991. Jacknis, Ira. Food in California Indian Culture. Hearst Museum Publications, Berkeley, CA, 2004. Copyright © 2003. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California, Berkeley. All Rights Reserved. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Table of Contents 1. Glossary 2. Topics of Discussion for Lessons 3. Map of California Cultural Areas 4. General Overview of California Indians 5. Plants and Plant Processing 6. Animals and Hunting 7. Food from the Sea and Fishing 8. Insects 9. Beverages 10. Salt 11. Drying Foods 12. Earth Ovens 13. Serving Utensils 14. Food Storage 15. Feasts 16. Children 17. California Indian Myths 18. Review Questions and Activities PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Glossary basin an open, shallow, usually round container used for holding liquids carbohydrate Carbohydrates are found in foods like pasta, cereals, breads, rice and potatoes, and serve as a major energy source in the diet. Central Valley The Central Valley lies between the Coast Mountain Ranges and the Sierra Nevada Mountain Ranges. It has two major river systems, the Sacramento and the San Joaquin. Much of it is flat, and looks like a broad, open plain. It forms the largest and most important farming area in California and produces a great variety of crops. -

The Carmel Pine Cone

VolumeThe 105 No. 42 Carmelwww.carmelpinecone.com Pine ConeOctober 18-24, 2019 T RUS T ED BY LOCALS AND LOVED BY VISI T ORS SINCE 1 9 1 5 Deal pending for Esselen tribe to buy ranch Cal Am takeover By CHRIS COUNTS But the takeover is not a done deal yet, despite local media reports to the contrary, Peter Colby of the Western study to be IF ALL goes according to plan, it won’t be a Silicon Rivers Conservancy told The Pine Cone this week. His Valley executive or a land conservation group that soon group is brokering the deal between the current owner of takes ownership of a remote 1,200-acre ranch in Big Sur the ranch, the Adler family of Sweden, and the Esselen released Nov. 6 but a Native American tribe with deep local roots. Tribe of Monterey County. “A contract for the sale is in place, By KELLY NIX but a number of steps need to be com- pleted first before the land is trans- THE LONG-AWAITED findings of a study to deter- ferred,” Colby said. mine the feasibility of taking over California American While Colby didn’t say how much Water’s local system and turning it into a government-run the land is selling for, it was listed operation will be released Nov. 6, the Monterey Peninsula at $8 million when The Pine Cone Water Management District announced this week. reported about it in 2017. But ear- The analysis was launched after voters in November lier this month, the California Nat- 2018 OK’d a ballot measure calling for the water district ural Resources Agency announced to use eminent domain, if necessary, to acquire Cal Am’s that something called “the Esselen Monterey Peninsula water system if the move was found Tribal Lands Conservation Project” to be cost effective. -

IACLEA Hurricane AAR BOOK.Book

CAMPUS PUBLIC SAFETY PREPAREDNESS FOR CATASTROPHIC EVENTS: LESSONS LEARNED FROM HURRICANES AND EXPLOSIVES This report was sponsored by The U. S. Department of Homeland Security, The Federal Bureau of Investigation, and The International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators CAMPUS PUBLIC SAFETY PREPAREDNESS FOR CATASTROPHIC EVENTS: LESSONS LEARNED FROM HURRICANES AND EXPLOSIVES This report was sponsored by The U. S. Department of Homeland Security, The Federal Bureau of Investigation, and The International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Government. Reference herein to any specific commercial products, processes, or services by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government. The information and statements contained in this document shall not be used for the purposes of advertising, nor to imply the endorsement or recommendation of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any of its employees make any warranty, express or implied, including but not limited to the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose. Further, neither the United States Government nor any of its employees assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product or process disclosed; nor do they represent that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. © 2006 by the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators (IACLEA) All Rights Reserved. This Printing: June 2006 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS Lessons Learned Preface ................................................................................................................ -

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay

Cultivating an Abundant San Francisco Bay Watch the segment online at http://education.savingthebay.org/cultivating-an-abundant-san-francisco-bay Watch the segment on DVD: Episode 1, 17:35-22:39 Video length: 5 minutes 20 seconds SUBJECT/S VIDEO OVERVIEW Science The early human inhabitants of the San Francisco Bay Area, the Ohlone and the Coast Miwok, cultivated an abundant environment. History In this segment you’ll learn: GRADE LEVELS about shellmounds and other ways in which California Indians affected the landscape. 4–5 how the native people actually cultivated the land. ways in which tribal members are currently working to restore their lost culture. Native people of San Francisco Bay in a boat made of CA CONTENT tule reeds off Angel Island c. 1816. This illustration is by Louis Choris, a French artist on a Russian scientific STANDARDS expedition to San Francisco Bay. (The Bancroft Library) Grade 4 TOPIC BACKGROUND History–Social Science 4.2.1. Discuss the major Native Americans have lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for thousands of years. nations of California Indians, Shellmounds—constructed from shells, bone, soil, and artifacts—have been found in including their geographic distribution, economic numerous locations across the Bay Area. Certain shellmounds date back 2,000 years activities, legends, and and more. Many of the shellmounds were also burial sites and may have been used for religious beliefs; and describe ceremonial purposes. Due to the fact that most of the shellmounds were abandoned how they depended on, centuries before the arrival of the Spanish to California, it is unknown whether they are adapted to, and modified the physical environment by related to the California Indians who lived in the Bay Area at that time—the Ohlone and cultivation of land and use of the Coast Miwok. -

1. Introduction

1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Ethnographic setting The Chimariko language was spoken in the nineteenth century in a few small villages in Trinity County, in north-western California. The villages were located along a twenty-mile stretch of the Trinity River and parts of the New River and South Fork River. In 1849, the Chimariko numbered around two hundred and fifty people. They were nearly extinct in 1906, except for a ‘toothless old woman and a crazy old man’, as well as ‘a few mixed bloods’ (Kroeber 1925:109). The ‘toothless old woman’ Kroeber refers to was most likely Polly Dyer and the ‘crazy old man’ Dr. Tom, also identified by Dixon (1910:295) as a ‘half-crazy old man’. The last speaker probably died in the 1940s. First contact with European explorers occurred early in the nineteenth century, in the 1820s or 1830s, when fur trappers came to the region. However, the tribe was left largely unaffected by this encounter (Dixon 1910:297). During the Gold Rush in the 1850s the Chimariko territory was overrun by gold seekers. Continuous gold mining activities in the region threatened the salmon supply, the main food source of the tribe, and led to a bitter conflict in the 1860s (Silver 1978a:205). The fights between European miners and the tribe resulted in the near annihilation of the Chimariko in the 1860s. The few survivors took refuge with the neighboring Shasta on the upper Salmon River or in Scott Valley or with the Hupa to the northwest (Dixon 1910:297). Once the gold was gone and the miners left the region, the survivors returned to their homes after years in exile (Silver 1978a:205). -

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River

The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River Mark Q. Sutton and David D. Earle Abstract century, although he noted the possible survival of The Desert Serrano of the Mojave River, little documented by “perhaps a few individuals merged among other twentieth century ethnographers, are investigated here to help un- groups” (Kroeber 1925:614). In fact, while occupation derstand their relationship with the larger and better known Moun- tain Serrano sociopolitical entity and to illuminate their unique of the Mojave River region by territorially based clan adaptation to the Mojave River and surrounding areas. In this effort communities of the Desert Serrano had ceased before new interpretations of recent and older data sets are employed. 1850, there were survivors of this group who had Kroeber proposed linguistic and cultural relationships between the been born in the desert still living at the close of the inhabitants of the Mojave River, whom he called the Vanyumé, and the Mountain Serrano living along the southern edge of the Mojave nineteenth century, as was later reported by Kroeber Desert, but the nature of those relationships was unclear. New (1959:299; also see Earle 2005:24–26). evidence on the political geography and social organization of this riverine group clarifies that they and the Mountain Serrano belonged to the same ethnic group, although the adaptation of the Desert For these reasons we attempt an “ethnography” of the Serrano was focused on riverine and desert resources. Unlike the Desert Serrano living along the Mojave River so that Mountain Serrano, the Desert Serrano participated in the exchange their place in the cultural milieu of southern Califor- system between California and the Southwest that passed through the territory of the Mojave on the Colorado River and cooperated nia can be better understood and appreciated. -

The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS IN AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY VOL. 6 NO. 2 THE GEOGRAPHY AND DIALECTS OF THE MIWOK INDIANS. BY S. A. BARRETT. CONTENTS. PAGE Introduction.--...--.................-----------------------------------333 Territorial Boundaries ------------------.....--------------------------------344 Dialects ...................................... ..-352 Dialectic Relations ..........-..................................356 Lexical ...6.................. 356 Phonetic ...........3.....5....8......................... 358 Alphabet ...................................--.------------------------------------------------------359 Vocabularies ........3......6....................2..................... 362 Footnotes to Vocabularies .3.6...........................8..................... 368 INTRODUCTION. Of the many linguistic families in California most are con- fined to single areas, but the large Moquelumnan or Miwok family is one of the few exceptions, in that the people speaking its various dialects occupy three distinct areas. These three areas, while actually quite near together, are at considerable distances from one another as compared with the areas occupied by any of the other linguistic families that are separated. The northern of the three Miwok areas, which may for con- venience be called the Northern Coast or Lake area, is situated in the southern extremity of Lake county and just touches, at its northern boundary, the southernmost end of Clear lake. This 334 University of California Publications in Am. Arch. -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

Open Dissertation Draft Revised Final.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School ICT AND STEM EDUCATION AT THE COLONIAL BORDER: A POSTCOLONIAL COMPUTING PERSPECTIVE OF INDIGENOUS CULTURAL INTEGRATION INTO ICT AND STEM OUTREACH IN BRITISH COLUMBIA A Dissertation in Information Sciences and Technology by Richard Canevez © 2020 Richard Canevez Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2020 ii The dissertation of Richard Canevez was reviewed and approved by the following: Carleen Maitland Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Daniel Susser Assistant Professor of Information Sciences and Technology and Philosophy Lynette (Kvasny) Yarger Associate Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Craig Campbell Assistant Teaching Professor of Education (Lifelong Learning and Adult Education) Mary Beth Rosson Professor of Information Sciences and Technology Director of Graduate Programs iii ABSTRACT Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have achieved a global reach, particularly in social groups within the ‘Global North,’ such as those within the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada. It has produced the need for a computing workforce, and increasingly, diversity is becoming an integral aspect of that workforce. Today, educational outreach programs with ICT components that are extending education to Indigenous communities in BC are charting a new direction in crossing the cultural barrier in education by tailoring their curricula to distinct Indigenous cultures, commonly within broader science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) initiatives. These efforts require examination, as they integrate Indigenous cultural material and guidance into what has been a largely Euro-Western-centric domain of education. Postcolonial computing theory provides a lens through which this integration can be investigated, connecting technological development and education disciplines within the parallel goals of cross-cultural, cross-colonial humanitarian development. -

An Overview of Ohlone Culture by Robert Cartier

An Overview of Ohlone Culture By Robert Cartier In the 16th century, (prior to the arrival of the Spaniards), over 10,000 Indians lived in the central California coastal areas between Big Sur and the Golden Gate of San Francisco Bay. This group of Indians consisted of approximately forty different tribelets ranging in size from 100–250 members, and was scattered throughout the various ecological regions of the greater Bay Area (Kroeber, 1953). They did not consider themselves to be a part of a larger tribe, as did well- known Native American groups such as the Hopi, Navaho, or Cheyenne, but instead functioned independently of one another. Each group had a separate, distinctive name and its own leader, territory, and customs. Some tribelets were affiliated with neighbors, but only through common boundaries, inter-tribal marriage, trade, and general linguistic affinities. (Margolin, 1978). When the Spaniards and other explorers arrived, they were amazed at the variety and diversity of the tribes and languages that covered such a small area. In an attempt to classify these Indians into a large, encompassing group, they referred to the Bay Area Indians as "Costenos," meaning "coastal people." The name eventually changed to "Coastanoan" (Margolin, 1978). The Native American Indians of this area were referred to by this name for hundreds of years until descendants chose to call themselves Ohlones (origination uncertain). Utilizing hunting and gathering technology, the Ohlone relied on the relatively substantial supply of natural plant and animal life in the local environment. With the exception of the dog, we know of no plants or animals domesticated by the Ohlone.