Tales from Greek Mythology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth Made Fact Lesson 8: Jason with Dr

Myth Made Fact Lesson 8: Jason with Dr. Louis Markos Outline: Jason Jason was a foundling, who was a royal child who grew up as a peasant. Jason was son of Eason. Eason was king until Pelias threw him into exile, also sending Jason away. When he came of age he decided to go to fulfill his destiny. On his way to the palace he helped an old man cross a river. When Jason arrived he came with only one sandal, as the other had been ripped off in the river. Pelias had been warned, “Beware the man with one sandal.” Pelias challenges Jason to go and bring back the Golden Fleece. About a generation or so earlier there had been a cruel king who tried to gain favor with the gods by sacrificing a boy and a girl. o Before he could do it, the gods sent a rescue mission. They sent a golden ram with a golden fleece that could fly. The ram flew Phrixos and Helle away. o The ram came to Colchis, in the southeast corner of the Black Sea. Helle slipped and fell and drowned in the Hellespont, which means Helle’s bridge (between Europe and Asia). o Phrixos sacrificed the ram and gave the fleece as a gift to the people of Colchis, to King Aeetes. o The Golden Fleece gives King Aeetes power. Jason builds the Argo. The Argonauts are the sailors of the Argo. Jason and the Argonauts go on the journey to get the Golden Fleece. Many of the Argonauts are the fathers of the soldiers of the Trojan War. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Phrixus and Helle

Phrixus and Helle In Orchomenus, a site in ancient Boeotia, king Athamas lived happily with his wife and their two children, Phrixus and Helle. Alas, the queen’s death put an abrupt end to their happiness. Athamas could not stand being alone for long, so he took a second wife, Ino. The new queen was terribly jealous of Phrixus and Helle and laid out an evil plan. She summoned the women of the land and gave them the following advice: “Here’s how you can make your husbands happy and secure their love and respect: take the seeds they are about to sow and bake them in the kiln. Your crops will double and your men will be forever grateful to you!” 6 The women believed the queen’s words and did as they were told. That year the fields yielded absolutely nothing. “Some god is punishing us,” the men muttered to themselves in despair. Athamas decided to ask the oracle of Delphi for help. His envoys, already bought off by Ino, brought back a terrible answer: “The gods are very angry at us! Our fields will remain barren unless you sacrifice your firstborn to Zeus!” “How could I ever do such a thing to my child?” cried out the desperate king and shut himself in his palace. But the news spread quickly and soon the famished people gathered outside his doors. Angry voices came from the mob. “O, king, obey the oracle, otherwise we are all going to starve to death!” Athamas had to give in to pressure. He took his unsuspecting son to Zeus’s altar. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop. -

Argonautika Entire First Folio

First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide ARGONAUTIKA adapted and directed by Mary Zimmerman based on the story by Apollonius of Rhodes January 15 to March 2, 2008 First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guide Table of Contents Page Number Welcome to the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s production of Argonautika! About Greek Theatre Brief History of the Audience………………………...1 This season, the Shakespeare Theatre Company The History of Greek Drama……………..……………3 presents eight plays by William Shakespeare and On Greek Society and Culture……………………….5 other classic playwrights. The mission of all About the Authors …………………………...……………6 Education Department programs is to deepen understanding, appreciation and connection to About the Play classic theatre in learners of all ages. One Synopsis of Argonautika……………..…………………7 approach is the publication of First Folio Teacher Curriculum Guides. The Myth Behind the Play ..…………………………..8 The Hero’s Quest…..………………………………………..9 For the 2007-08 season, the Education Fate and Free Will…...………………..………..………..10 Department will publish First Folio Teacher Mythology: More than just a good story…...11 Curriculum Guides for our productions of Glossary of Terms and Characters..…………….12 Tamburlaine, Taming of the Shrew, Argonautika Questing…………………………………………………..…….14 and Julius Caesar. First Folio Guides provide information and activities to help students form Classroom Connections a personal connection to the play before • Before the Performance……………………………15 attending the production at the Shakespeare Journey Game Theatre Company. First Folio Guides contain God and Man material about the playwrights, their world and It’s Greek to Me the plays they penned. Also included are The Hero’s Journey approaches to explore the plays and productions in the classroom before and after (Re)Telling Stories the performance. -

Jason and the Golden Fleece by Max I

Jason and the Golden Fleece By Max I. A long time ago, a child named Jason was born in the small kingdom of Iolcus, which was in Northern Greece. He was born before actual Greek history, in a time where Gods and heroes still existed. He was the son of King Aeson, who ruled Iolcus fairly and justly. His mother was descended from Poseidon, the god of the sea. Therefore, Jason had royal blood and divine blood as well. Jason grew up to be a good looking and good-natured boy. He was polite to everybody and everybody liked him. And everybody knew that Jason would inherit the throne of Iolcus. He was a good friend of Max, who was a foreigner from Colchis. In fact, he was one of the most valuable people on the journey because he was from where the Golden Fleece was hidden. 10 years before Jason was born, a king and queen called Athamas and Nephele ruled in Northern Greece. However, king Athamas grew tired of his kind, virtuous queen, and sent her away so he could marry a cruel woman named Ino. However, Ino was so cruel she resolved to murder the king’s children, as she was mad after a argument with Athamas. Queen Nephele rushed back to save her children and enlisted the help of the God Hermes. Hermes created a massive golden ram to carry the two children to safety. Their names were Phrixus and Helle. The Ram carried them all the way to Colchis, where they could seek shelter. However, as they were flying over a great river that separates Europe from Asia, Helle fell off the Ram to her death. -

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

Mythology Study Questions

Mythology by Edith Hamilton Study Questions – Freshman Class Part I 1. List the twelve Olympian Gods (Greek and Roman names) and give a brief description of their role, character and domain. 2. Who was Peresphone and what happened to her? What happened on earth because of it? 3. How did the Titan Cronus come to power in the universe? 4. Who was Cronus’ queen? 5. Why did Cronus swallow his children? 6. Who helped Zeus in his battle against Cronus? 7. Describe Typhon. 8. What was in Pandora’s box? 9. What happened to Io? 10. What happened to Narcissus? Part II 1. Why does Venus hate Psyche so much? 2. Why does she eventually consent to the marriage of Cupid and Psyche? 3. How do Pyramus and Thisbe die? 4. What goes wrong with Orpheus’ rescue attempt? 5. How are Phrixus and Helle saved from human sacrifice? 6. Why does Jason go on the quest for the Golden Fleece? 7. How does the company lose Hercules? 8. How is it that Medea falls in love with Jason? 9. List three good things that Medea does for Jason. 10. List thee evil things that Medea does. 11. What does Phaethon ask of the Sun? 12. What does Belleronphon desire? 13. What is the mistake of Icarus? Part III 1. Why does Perseus have to get the Gorgon’s head? 2. How does Perseus get the witches to tell him where to find Medusa? 3. How does Perseus strike Medusa with a sword without being turned to stone? 4. What three gifts does Perseus receive from the Hyperboreans? 5. -

Pasolini's Medea

Faventia 37, 2015 91-122 Pasolini’s Medea: using μῦθος καὶ σῆμα to denounce the catastrophe of contemporary life* Pau Gilabert Barberà Universitat de Barcelona. Departament de Filologia Clàssica, Romànica i Semítica [email protected] Reception: 01/02/2012 Abstract From Pasolini’s point of view, Medea’s tragedy is likewise the tragedy of the contemporary Western world and cinema is the semiology of reality. His Medea thus becomes an ancient myth pregnant with signs to be interpreted by attentive viewers. The aim of this article is to put forward reasoned interpretations based on a close analysis of the images and verbal discourses (lógoi) of Pasolini’s script, ever mindful of the explanations given by the director himself that have been published in interviews, articles and other texts. Keywords: Pier Paolo Pasolini; Medea; Greek tragedy; classical tradition; cinema; semiology Resumen. La Medea de Pasolini: utilizar μῦθος καὶ σῆμα para denunciar la catástrofe del mundo contemporáneo Desde el punto de vista de Pasolini, la tragedia de Medea equivale a la tragedia del mundo con- temporáneo y el cine es la semiología de la realidad. Su Medea deviene así un mito antiguo repleto de signos que requieren la interpretación de espectadores atentos. El objetivo de este artículo es proponer interpretaciones razonadas basadas en el análisis minucioso de las imágenes y de los dis- cursos verbales (lógoi) del guion de Pasolini, siempre desde el conocimiento de las explicaciones dadas por el mismo director publicadas en entrevistas, artículos y otros textos. Palabras clave: Pier Paolo Pasolini; Medea; tragedia griega; tradición clásica; cine; semiología * This article is one of the results of a research project endowed by the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia “Usos y construcción de la tragedia griega y de lo clásico” –reference: FFI2009-10286 (subprograma FILO); main researcher: Prof. -

Unit 5: Epic and Myth

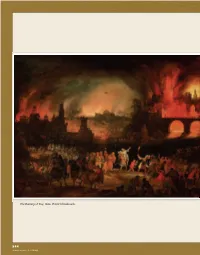

The Burning of Troy, 1606. Pieter Schoubroeck. 944 Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS UNIT FIVE Epic and Myth Looking Ahead Many centuries ago, before books, magazines, paper, and pencils were invented, people recited their stories. Some of the stories they told offered explanations of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, or the culture’s customs or beliefs. Other stories were meant for entertainment. Taken together, these stories—these myths, epics, and legends—tell a history of loyalty and betrayal, heroism and cowardice, love and rejection. In this unit, you will explore the literary elements that make them unique. PREVIEW Big Ideas and Literary Focus BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 1 Journeys Hero BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 2 Courage and Cleverness Archetype OBJECTIVES In learning about the genres of epic and myth, • identifying and exploring literary elements you will focus on the following: significant to the genres • understanding characteristics of epics and myths • analyzing the effect that these literary elements have upon the reader 945 Genre Focus: Epic and Myth What is unique about epics and myths? Why do we read stories from the distant past? answer. He thought that in order for us to under- Why should we care about heroes and villains long stand the people we are today, we have to learn dead? About cities and palaces that were destroyed about those who came before us. One way to do centuries before our time? The noted psychologist that, Jung believed, was to read the myths and and psychiatrist Carl Jung thought he knew the epics of long ago. -

Collection of Hesiod Homer and Homerica

COLLECTION OF HESIOD HOMER AND HOMERICA Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns, and Homerica This file contains translations of the following works: Hesiod: "Works and Days", "The Theogony", fragments of "The Catalogues of Women and the Eoiae", "The Shield of Heracles" (attributed to Hesiod), and fragments of various works attributed to Hesiod. Homer: "The Homeric Hymns", "The Epigrams of Homer" (both attributed to Homer). Various: Fragments of the Epic Cycle (parts of which are sometimes attributed to Homer), fragments of other epic poems attributed to Homer, "The Battle of Frogs and Mice", and "The Contest of Homer and Hesiod". This file contains only that portion of the book in English; Greek texts are excluded. Where Greek characters appear in the original English text, transcription in CAPITALS is substituted. PREPARER'S NOTE: In order to make this file more accessable to the average computer user, the preparer has found it necessary to re-arrange some of the material. The preparer takes full responsibility for his choice of arrangement. A few endnotes have been added by the preparer, and some additions have been supplied to the original endnotes of Mr. Evelyn-White's. Where this occurs I have noted the addition with my initials "DBK". Some endnotes, particularly those concerning textual variations in the ancient Greek text, are here ommitted. PREFACE This volume contains practically all that remains of the post- Homeric and pre-academic epic poetry. I have for the most part formed my own text. In the case of Hesiod I have been able to use independent collations of several MSS. by Dr. -

Constellation Legends

Constellation Legends by Norm McCarter Naturalist and Astronomy Intern SCICON Andromeda – The Chained Lady Cassiopeia, Andromeda’s mother, boasted that she was the most beautiful woman in the world, even more beautiful than the gods. Poseidon, the brother of Zeus and the god of the seas, took great offense at this statement, for he had created the most beautiful beings ever in the form of his sea nymphs. In his anger, he created a great sea monster, Cetus (pictured as a whale) to ravage the seas and sea coast. Since Cassiopeia would not recant her claim of beauty, it was decreed that she must sacrifice her only daughter, the beautiful Andromeda, to this sea monster. So Andromeda was chained to a large rock projecting out into the sea and was left there to await the arrival of the great sea monster Cetus. As Cetus approached Andromeda, Perseus arrived (some say on the winged sandals given to him by Hermes). He had just killed the gorgon Medusa and was carrying her severed head in a special bag. When Perseus saw the beautiful maiden in distress, like a true champion he went to her aid. Facing the terrible sea monster, he drew the head of Medusa from the bag and held it so that the sea monster would see it. Immediately, the sea monster turned to stone. Perseus then freed the beautiful Andromeda and, claiming her as his bride, took her home with him as his queen to rule. Aquarius – The Water Bearer The name most often associated with the constellation Aquarius is that of Ganymede, son of Tros, King of Troy.