Section 3 – Takata Whenua Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Precision 10Be Chronology of Moraines in the Southern Alps Indicates Synchronous Cooling in Antarctica and New Zealand 42,000 Years Ago ∗ Samuel E

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 405 (2014) 194–206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl High-precision 10Be chronology of moraines in the Southern Alps indicates synchronous cooling in Antarctica and New Zealand 42,000 years ago ∗ Samuel E. Kelley a, ,1, Michael R. Kaplan b, Joerg M. Schaefer b, Bjørn G. Andersen c,2, David J.A. Barrell d, Aaron E. Putnam b, George H. Denton a, Roseanne Schwartz b, Robert C. Finkel e, Alice M. Doughty f a Department of Earth Sciences and Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469, USA b Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory, Palisades, NY 10964, USA c Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway d GNS Science, Dunedin, New Zealand e Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA 94550, USA f Department of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03750, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Millennial-scale temperature variations in Antarctica during the period 80,000 to 18,000 years ago are Received 13 July 2013 known to anti-correlate broadly with winter-centric cold–warm episodes revealed in Greenland ice Received in revised form 22 July 2014 cores. However, the extent to which climate fluctuations in the Southern Hemisphere beat in time with Accepted 25 July 2014 Antarctica, rather than with the Northern Hemisphere, has proved a controversial question. In this study Available online 16 September 2014 we determine the ages of a prominent sequence of glacial moraines in New Zealand and use the results Editor: G.M. -

Waitaki Clutha

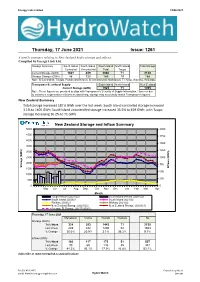

Energy Link Limited 18/06/2021 Waitaki Thursday, 17 June 2021 Issue: 1261 A weekly summary relating to New Zealand hydro storage and inflows. Compiled by Energy Link Ltd. Storage Summary South Island South Island South Island North Island Total Storage Controlled Uncontrolled Total Taupo Current Storage (GWh) 1601 459 2060 71 2130 Storage Change (GWh) 48 120 169 19 188 Note: SI Controlled; Tekapo, Pukaki and Hawea: SI Uncontrolled; Manapouri, Te Anau, Wanaka, Wakatipu Transpower Security of Supply South Island North Island New Zealand Current Storage (GWh) 1925 71 1995 Note: These figures are provided to align with Transpower's Security of Supply information. However due to variances in generation efficiencies and timing, storage may not exactly match Transpower's figures. New Zealand Summary Total storage increased 187.6 GWh over the last week. South Island controlled storage increased 3.1% to 1601 GWh; South Island uncontrolled storage increased 35.5% to 459 GWh; with Taupo storage increasing 36.2% to 71 GWh. New Zealand Storage and Inflow Summary 5000 2000 4500 1750 4000 1500 3500 1250 3000 2500 1000 Clutha 2000 750 Storage (GWh) Storage 1500 (GWh) Inflows 500 1000 250 500 0 0 May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Month Taupo Inflows (2021/22) South Island inflows (2021/22) South Island 2020/21 South Island 2021/22 Waikato 2020/21 Waikato 2021/22 New Zealand Storage (2021/22) New Zealand Storage (2020/21) Average SI Storage (16/17-20/21) Thursday, 17 June 2021 Manapouri Clutha Waitaki Waikato NZ Storage (GWh) This Week 324 293 1443 71 2130 Last Week 249 242 1400 52 1943 % Change 30.0% 20.9% 3.1% 36.2% 9.7% Inflow (GWh) This Week 166 117 173 51 507 Last Week 90 60 146 35 331 % Change 84.3% 96.1% 17.9% 46.8% 53.1% Subscribe at www.energylink.co.nz/publications Ph (03) 479 2475 Consultancy House Email: [email protected] Hydro Watch Dunedin Energy Link Limited 18/06/2021 Lake Levels and Outflows Catchment Lake Level Storage Outflow Outflow (m. -

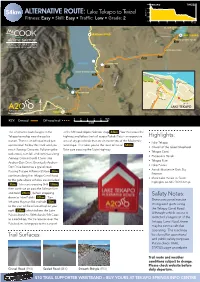

Alternative Route to Twizel

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd GLENTANNER PARK CENTRE LAKE PUKAKI LAKE TEKAPO 54KM LANDSLIP CREEK ALTERNATIVE ROUTE TO TWIZEL TAKAPÕ LAKE TEKAPO MT JOHN OBSERVATORY BRAEMAR ROAD TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO Tekapo Powerhouse Rd TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km Hayman Rd Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS TEKAPO CANAL 9km 15km 24km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road 30km Lakeside Dr TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO 35km Tek Church of the apo-Twizel Rd Good Shepherd 8 MARY RANGES Dog Monument SALMONFA RM TO SALMON SHOP SH80 TEKAPO RIVER SH8 r s D 44km e r r C e i e Pi g n on SALMON SHOP n Roto Pl o RUATANIWHA i e a e P r r D CONSERVATION PARK o r A Scott Pond STARTING POINT PUKAKI CANAL SH8 Aorangi Cres 8 8 F Rd Lakeside airlie kapo -Te Car Park PUKAKI RIVER Lochinvar Ave Allan St Lilybank Rd Glen Lyon Rd r D n o P l Glen Lyon Rd ilt ollock P Andrew Don Dr am Old Glen Lyon Rd H N Pukaki Flats Track Rise TWIZEL 54km Murray Pl Rankin PUKAKI FLATS OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA SH8KEY: Fitness Easy Traffic Low 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL Onroad left onto Hayman Rd and ride to the Off-road trail 700 start of the off-road Trail on your right Skill Easy Grade 2 Information Centre 35km which follows the Lake Pukaki 600 Picnic Area shoreline. -

Lake Tekapo to Twizel Highlights

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL 700 54km ALTERNATIVEGLENTANNER PARK CENTRE ROUTE: Lake Tekapo to Twizel 600 LANDSLIP CREEK ELEVATION Fitness: Easy • Skill: Easy • Traffic: Low • Grade: 2 500 400 KM LAKE PUKAKI 0 10 20 30 40 50 MT JOHN OBSERVATORY LAKE TEKAPO BRAEMAR ROAD Tekapo Powerhouse Rd LAKE TEKAPO TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km TRAIL GUARDIAN Hayman Rd SALMON FARM TO SALMON SHOP Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS 9km TEKAPO CANAL 15km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM 24km TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road LAKE TEKAPO 30km Lakeside Dr Te kapo-Twizel Rd Church of the 8 Good Shepherd Dog Monument MARY RANGES SH80 35km r s D TEKAPO RIVERe SH8 r r 44km C e i e Pi g n on n Roto Pl o i e a e P SALMON SHOP r r D o r A Scott Pond Aorangi Cres 8 PUKAKI CANAL SH8 F Rd airlie-Tekapo PUKAKI RIVER Allan St Glen Lyon Rd Glen Lyon Rd LAKE TEKAPO Andrew Don Dr Old Glen Lyon Rd Pukaki Flats Track Murray Pl TWIZEL PUKAKI FLATS Mapwww.alps2ocean.com current as of 28/7/17 N 54km OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA 0 1 2 3 4 5km KEY: Onroad Off-road trail SH8 Scale The alternative route begins in the at the Mt Cook Alpine Salmon shop 44km . You then cross the Tekapo township near the police highway and follow the trail across Pukaki Flats – an expansive Highlights: station. -

Aoraki Mt Cook

Anna Thompson: Aoraki/Mt Cook – cultural icon or tourist “object” The natural areas of New Zealand, particularly national parks, are a key attraction for domestic and international visitors who venture there for a variety of recreation and leisure purposes. This paper discusses the complex cultural values and timeless quality of an iconic landmark - Aoraki/Mt Cook – which is located within the ever-changing Mackenzie Basin. It explores the various human values for the mountain and the surrounding regional landscape which has become iconic in its own right. The landscape has economic, environmental, scientific and social significance with intangible heritage values and connotations of sacred and sublime experiences of place. The paper considers Aoraki/Mt Cook as a ‘wilderness’ region that is also a focal point not only for local inhabitants but also for travellers sightseeing and recreating in the area. The paper also explores how cultural values for the mountain are interpreted to visitors in an attempt to convey a sense of ‘place’. Finally the Mackenzie Basin is discussed as a special ‘in-between’ place – that should be considered significant in its own right and not just as a ‘foreground’ or ‘frame’ for viewing the Southern Alps and Aoraki/Mt Cook itself. The Mackenzie has aesthetic scenic qualities that need careful management of activities such as recent attempts to establish industrialised, dairy factory farming (which does not complement more sustainable economic and social development in the region). Sympathetic projects such as the Nga Haerenga (Ocean to the Alps) cycle way are also under development to encourage activity within the landscape – in conflict with the dairying and other activities that impact negatively on the natural resources of the region.1 Introduction – cultural values for landscape and ‘place’ Aotearoa New Zealand is regarded by many as a ‘young country’ – the last indigenous populated country to be colonised by European cultures. -

Twizel Highlights

FAIRLIE | LAKE TEKAPO | AORAKI / MOUNT COOK | TWIZEL HIGHLIGHTS FAIRLIE Explore local shops | Cafés KIMBELL Walking trails | Art gallery BURKES PASS Shopping & art | Heritage walk | Historic Church LAKE TEKAPO Iconic Church | Walks/trails LAKE PUKAKI Beautiful scenery | Lavender farm GLENTANNER Beautiful vistas | 18kms from Aoraki/Mount Cook Village AORAKI/MOUNT COOK Awe-inspiring mountain views | Adventure playground TWIZEL Quality shops | Eateries | Five lakes nearby | Cycling Welcome to the Mackenzie Region The Mackenzie Region spaces are surrounded by SUMMER provides many WINTER in the Mackenzie winter days are perfect is located at the heart snow-capped mountains, experiences interacting is unforgettable with for scenic flights and the p18 FAIRLIE of New Zealand’s South including New Zealand’s with the natural landscape uncrowded snow fields and nights crisp and clear for Island, 2.5 hour’s drive from tallest, Aoraki/Mount Cook, of our unique region, from unique outdoor experiences spectacular stargazing. Christchurch or 3 hours from with golden tussocks giving star gazing tours and scenic as well as plenty of ways p20 LAKE TEKAPO Be spoilt for choice Dunedin/Queenstown. way to turquoise-blue lakes, flights, to hot pools and to relax after a day on the with a wide variety of Explore one of the most fed by meltwater from cycle trails. Check out 4WD slopes. Ride the snow tube, accommodation styles, eat picturesque regions offering numerous glaciers. tours, farm tours and boating visit our family friendly snow local cuisine, and smile at p30 AORAKI/MOUNT COOK bright, sunny days and dark experiences or get your fields or relax in the hot pools. -

Download File

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 382 (2013) 98–110 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Warming and glacier recession in the Rakaia valley, Southern Alps of New Zealand, during Heinrich Stadial 1 ∗ Aaron E. Putnam a,b, , Joerg M. Schaefer a,c, George H. Denton b, David J.A. Barrell d, Bjørn G. Andersen e,1, Tobias N.B. Koffman b,AnnV.Rowanf, Robert C. Finkel g, Dylan H. Rood h,i, Roseanne Schwartz a, Marcus J. Vandergoes j, Mitchell A. Plummer k, Simon H. Brocklehurst l, Samuel E. Kelley m, Kathryn L. Ladig b a Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, 61 Rt. 9W, Palisades, NY 10964, USA b School of Earth and Climate Sciences and Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469, USA c Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Columbia University, New York, NY 10027, USA d GNS Science, Private Bag 1930, Dunedin 9054, New Zealand e Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo 0316, Norway f Centre for Glaciology, Department of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB Wales, UK g Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, CA 95064, USA h CAMS, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA 94550, USA i Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC), East Kilbride G75 0QF, UK j GNS Science, 1 Fairway Drive, PO Box 30-368, Lower Hutt 5040, New Zealand k Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID 83415-2107, USA l School of Earth, Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK m Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA article info abstract Article history: The termination of the last ice age featured a major reconfiguration of Earth’s climate and cryosphere, Received 29 April 2013 yet the underlying causes of these massive changes continue to be debated. -

Lake Level History Electricity Commission

Lake Level History Electricity Commission Electricity Commission Lake Level History Prepared By Opus International Consultants Limited James Knight Environmental Hydrologist Level 9, Majestic Centre, 100 Willis Street PO Box 12 003, Wellington 6144, New Zealand Reviewed By Telephone: +64 4 471 7000 Jack McConchie Facsimile: +64 4 499 3699 Principal Water Resource Scientist Date: 27 February 2009 Horace Freestone Reference: 350712.00 Principal Hydrologist Status: Final Draft © Opus International Consultants Limited 2009 Contents 350712.00 February 2009 i Contents Contents 1 Hydro Lakes ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Accuracy....................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 North Island .................................................................................................................. 2 1.4 South Island ................................................................................................................. 4 2 North Island.......................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Lake Taupo .................................................................................................................. 5 2.2 Lake Waikaremoana ................................................................................................. -

New Zealand Touring Map

Manawatawhi / Three Kings Islands NEW ZEALAND TOURING MAP Cape Reinga Spirits North Cape (Otoa) (Te Rerengawairua) Bay Waitiki North Island Landing Great Exhibition Kilometres (km) Kilometres (km) N in e Bay Whangarei 819 624 626 285 376 450 404 698 539 593 155 297 675 170 265 360 658 294 105 413 849 921 630 211 324 600 863 561 t Westport y 1 M Wellington 195 452 584 548 380 462 145 355 334 983 533 550 660 790 363 276 277 456 148 242 352 212 649 762 71 231 Wanaka i l Karikari Peninsula e 95 Wanganui 370 434 391 222 305 74 160 252 779 327 468 454 North Island971 650 286 508 714 359 159 121 499 986 1000 186 Te Anau B e a Wairoa 380 308 252 222 296 529 118 781 329 98 456 800 479 299 348 567 187 189 299 271 917 829 Queenstown c Mangonui h Cavalli Is Themed Highways29 350 711 574 360 717 905 1121 672 113 71 10 Thames 115 205 158 454 349 347 440 107 413 115 Picton Kaitaia Kaeo 167 86 417 398 311 531 107 298 206 117 438 799 485 296 604 996 1107 737 42 Tauranga For more information visit Nelson Ahipara 1 Bay of Tauroa Point Kerikeri Islands Cape Brett Taupo 82 249 296 143 605 153 350 280 newzealand.com/int/themed-highways643 322 329 670 525 360 445 578 Mt Cook (Reef Point) 87 Russell Paihia Rotorua 331 312 225 561 107 287 234 1058 748 387 637 835 494 280 Milford Sound 11 17 Twin Coast Discovery Highway: This route begins Kaikohe Palmerston North 234 178 853 401 394 528 876 555 195 607 745 376 Invercargill Rawene 10 Whangaruru Harbour Aotearoa, 13 Kawakawa in Auckland and travels north, tracing both coasts to 12 Poor Knights New Plymouth 412 694 242 599 369 721 527 424 181 308 Haast Opononi 53 1 56 Cape Reinga and back. -

SECTION 1: Aoraki/Mt Cook to Braemar Road Trail Surfaces

800 AORAKI / MT COOK BRAEMAR ROAD 700 SECTION 1: Aoraki/Mt Cook to Braemar Road 600 35km ELEVATION Fitness: Easy • Skill: Moderate • Traffic: Low • Grade: 2 500 400 0 10 20 30 40 50 KM The Alps 2 Ocean Cycle Trail starts at the White Horse Hill Campground, AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND which is 2km north of Mt Cook MOUNT COOK VILLAGE Village. From here, an off-road trail 2km takes you to Mount Cook Airport BURNETT MOUNTAINS 8km , where riders will need to MOUNT COOK AIRPORT make a short helicopter flight across the Tasman River to Tasman Point. 8km TASMAN POINT Travelling in a helicopter across a Tasman Valley glacially-fed braided river with New Zealand’s highest mountain in view is Track NEUMANN RANGE a must do. The helicopter can carry up to 6 passengers at a time (depending on weight limits). TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER BEN OHAU RANGE Heliworks: 0800 666 668 [Mt Cook Airport] SH80 Helicopter Line: 0800 650 651 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd 18km [Glentanner Park Centre] From Tasman Point it’s 10.6km to the Jollie Car Park at the top of Hayman Rd 18km . This track is rough in GLENTANNER PARK CENTRE places and includes several creek LANDSLIP CREEK crossings. On a clear day this section of trail offers views of Aoraki/Mt Cook, 27km which at 3,754 metres towers above LAKE PUKAKI a range of snow washed peaks in the Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park. From the car park, it’s 16.8km on gravel road to Braemar Rd. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 30 July 2019 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Sutherland, Jenna L. and Carrivick, Jonathan L. and Evans, David J.A. and Shulmeister, James and Quincey, Duncan J. (2019) 'The Tekapo Glacier, New Zealand, during the Last Glacial Maximum : an active temperate glacier inuenced by intermittent surge activity.', Geomorphology., 343 . pp. 183-210. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2019.07.008 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2019 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license. (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Geomorphology 343 (2019) 183–210 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph The Tekapo Glacier, New Zealand, during the Last Glacial Maximum: An active temperate glacier influenced by intermittent surge activity Jenna L. -

Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park Management Plan 2004 11

1 Introduction In New Zealand, national parks are areas of publicly-owned land that are preserved in perpetuity for their intrinsic worth and for the benefit, use and enjoyment of the public. They consist of areas that contain scenery of such distinctive quality, ecological systems, or natural features so beautiful, unique or scientifically important, that their preservation is in the national interest. Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park (see Figure 1) protects qualities and attractions that range from historic features of local interest, through ecosystems of national scientific importance, to major physical features of international significance. The Park, together with Westland/Tai Poutini and Fiordland National Parks, comprised New Zealand’s first world heritage area in 1986. In 1989 the much larger 2.6 million hectare South West New Zealand (Te Wahipounamu) World Heritage Area included the three Parks, recognised by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) as one of the world’s outstanding natural areas. The Park is unique in the New Zealand context in that it contains a cross-section of landforms and vegetation that extends from the South Island high country’s braided riverbeds to the highest peaks of the Southern Alps/Ka Tiritiri o te Moana. It also includes New Zealand’s highest mountain Aoraki/Mount Cook, which is also highly significant to Ngäi Tahu as their most sacred mountain. Public recreation and tourism interests in the best-known features, the mountains and the glaciers, have been significant for over a century. For this reason, accommodation, guiding and ski plane services have a long-standing tradition in the Park.