Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wrybill <I>Anarhynchus Frontalis</I>: a Brief Review of Status, Threats and Work in Progress

The Wrybill Anarhynchus frontalis: a brief review of status, threats and work in progress ADRIAN C. RIEGEN '1 & JOHN E. DOWDING 2 •231 ForestHill Road, Waiatarua, Auckland 8, NewZealand, e-maih riegen @xtra.co. nz; 2p.o. BOX36-274, Merivale, Christchurch 8030, New Zealand, e-maih [email protected]. nz Riegen,A.C. & Dowding, J.E. 2003. The Wrybill Anarhynchusfrontalis:a brief review of status,threats and work in progress.Wader Study Group Bull. 100: 20-24. The Wrybill is a threatenedplover endemic to New Zealandand unique in havinga bill curvedto the right.It is specializedfor breedingon bareshingle in thebraided riverbeds of Canterburyand Otago in the SouthIsland. After breeding,almost the entirepopulation migrates north and wintersin the harboursaround Auckland. The speciesis classifiedas Vulnerable. Based on countsof winteringflocks, the population currently appears to number4,500-5,000 individuals.However, countingproblems mean that trendsare difficult to determine. The mainthreats to theWrybill arebelieved to be predationon thebreeding grounds, degradation of breeding habitat,and floodingof nests.In a recentstudy in the MackenzieBasin, predation by introducedmammals (mainly stoats,cats and possibly ferrets) had a substantialimpact on Wrybill survivaland productivity. Prey- switchingby predatorsfollowing the introductionof rabbithaemorrhagic disease in 1997 probablyincreased predationrates on breedingwaders. A recentstudy of stoatsin the TasmanRiver showedthat 11% of stoat densexamined contained Wrybill remains.Breeding habitat is beinglost in somerivers and degraded in oth- ers,mainly by waterabstraction and flow manipulation,invasion of weeds,and human recreational use. Flood- ing causessome loss of nestsbut is alsobeneficial, keeping nesting areas weed-free. The breedingrange of the speciesappears to be contractingand fragmenting, with the bulk of the popula- tion now breedingin three large catchments. -

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31St October to 16Th November 2016 (17 Days)

New Zealand Comprehensive II Trip Report 31st October to 16th November 2016 (17 days) The Critically Endangered South Island Takahe by Erik Forsyth Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Erik Forsyth RBL New Zealand – Comprehensive II Trip Report 2016 2 Tour Summary New Zealand is a must for the serious seabird enthusiast. Not only will you see a variety of albatross, petrels and shearwaters, there are multiple- chances of getting out on the high seas and finding something unusual. Seabirds dominate this tour and views of most birds are alongside the boat. There are also several land birds which are unique to these islands: kiwis - terrestrial nocturnal inhabitants, the huge swamp hen-like Takahe - prehistoric in its looks and movements, and wattlebirds, the saddlebacks and Kokako - poor flyers with short wings Salvin’s Albatross by Erik Forsyth which bound along the branches and on the ground. On this tour we had so many highlights, including close encounters with North Island, South Island and Little Spotted Kiwi, Wandering, Northern and Southern Royal, Black-browed, Shy, Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses, Mottled and Black Petrels, Buller’s and Hutton’s Shearwater and South Island Takahe, North Island Kokako, the tiny Rifleman and the very cute New Zealand (South Island wren) Rockwren. With a few members of the group already at the hotel (the afternoon before the tour started), we jumped into our van and drove to the nearby Puketutu Island. Here we had a good introduction to New Zealand birding. Arriving at a bay, the canals were teeming with Black Swans, Australasian Shovelers, Mallard and several White-faced Herons. -

Aoraki Mount Cook

Aoraki Mount Cook: Environmental Change on an Iconic Mountaineering Route Authors: Heather Purdie, and Tim Kerr Source: Mountain Research and Development, 38(4) : 364-379 Published By: International Mountain Society URL: https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-18-00042.1 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Mountain-Research-and-Development on 1/23/2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Mountain Research and Development (MRD) MountainResearch An international, peer-reviewed open access journal Systems knowledge published by the International Mountain Society (IMS) www.mrd-journal.org Aoraki Mount Cook: Environmental Change on an Iconic Mountaineering Route Heather Purdie1* and Tim Kerr2 * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 University of Canterbury, Department of Geography, Arts Road, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 2 Aqualinc Research Ltd, Aviation House, Unit 3, 12 Orchard Road, Burnside, Christchurch 8053, New Zealand Ó 2018 Purdie and Kerr. -

High-Precision 10Be Chronology of Moraines in the Southern Alps Indicates Synchronous Cooling in Antarctica and New Zealand 42,000 Years Ago ∗ Samuel E

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 405 (2014) 194–206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl High-precision 10Be chronology of moraines in the Southern Alps indicates synchronous cooling in Antarctica and New Zealand 42,000 years ago ∗ Samuel E. Kelley a, ,1, Michael R. Kaplan b, Joerg M. Schaefer b, Bjørn G. Andersen c,2, David J.A. Barrell d, Aaron E. Putnam b, George H. Denton a, Roseanne Schwartz b, Robert C. Finkel e, Alice M. Doughty f a Department of Earth Sciences and Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469, USA b Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory, Palisades, NY 10964, USA c Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway d GNS Science, Dunedin, New Zealand e Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA 94550, USA f Department of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03750, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Millennial-scale temperature variations in Antarctica during the period 80,000 to 18,000 years ago are Received 13 July 2013 known to anti-correlate broadly with winter-centric cold–warm episodes revealed in Greenland ice Received in revised form 22 July 2014 cores. However, the extent to which climate fluctuations in the Southern Hemisphere beat in time with Accepted 25 July 2014 Antarctica, rather than with the Northern Hemisphere, has proved a controversial question. In this study Available online 16 September 2014 we determine the ages of a prominent sequence of glacial moraines in New Zealand and use the results Editor: G.M. -

MOUNT COOK – Glaciers and Glacier Lakes Topo50 Maps: BX15 Fox Glacier GPS: NZTM on WGS84

MOUNT COOK – glaciers and glacier lakes Topo50 Maps: BX15 Fox Glacier GPS: NZTM on WGS84 How to get to START – Hooker Track and Glacier First of all ensure you are on the South Island Mount Cook Village is reached via SH80 which goes virtually due North when SH8 turns to the East just north of Twizel almost halfway between Queenstown and Christchurch. A small, sign-posted gravel road branches off to the north east near the end of the asphalt road just before Mount Cook Village – follow this road to the end and park in the car park (WP01). The tramping route is the red line on the left hand side of the map opposite whilst the gravel road is shown in blue coming out of Mount Cook Village Rough Description: The whole walk from the car park (WP993) to the edge of the Hooker Glacial Lake (WP07) and back takes less than 4 hours. On the way one passes the Mount Cook Memorial (M), the Mueller Glacial Lake and the Stocking Stream Shelter. This is an easy walk but there are one or two slightly tricky bits over rock outcrops to Blue lines are motorable roads and red lines are walks. negotiate. A secondary walk of 20 minutes can later be taken to the edge of the Tasman Glacier lake. Detail: From the car park (WP01743masl) follow the sign-posted manicured track past the DOC toilets in an eastwardly direction. This track is lined with the spiky plant Mataguri so avoid close encounters. Within minutes the access branch to the Mount Cook Memorial (WPM782masl) goes off left – this is worth checking as it is a reminder that Mount Cook must be treated with respect. -

Social Play in Kaka (Nestor Meridionalis) with Comparisons to Kea (Nestor Notabilis)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 2004 Social Play in Kaka (Nestor meridionalis) with Comparisons to Kea (Nestor notabilis) Judy Diamond University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Alan B. Bond University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons Diamond, Judy and Bond, Alan B., "Social Play in Kaka (Nestor meridionalis) with Comparisons to Kea (Nestor notabilis)" (2004). Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences. 34. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscibehavior/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Behavior and Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Behaviour 141 (2004), pp. 777-798. Copyright © 2004 Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden. Used by permission. Social Play in Kaka (Nestor meridionalis) with Comparisons to Kea (Nestor notabilis) Judy Diamond University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588, USA Alan B. Bond School of Biological Sciences, University of Nebraska–Lincoln, Lincoln, NE 68588, USA Corresponding author—J. Diamond, [email protected] Summary Social play in the kaka (Nestor meridionalis), a New Zealand parrot, is described and contrasted with that of its closest relative, the kea (Nestor notabilis), in one of the first comparative studies of social play in closely related birds. Most play ac- tion patterns were clearly homologous in these two species, though some con- trasts in the form of specific play behaviors, such as kicking or biting, could be attributed to morphological differences. -

WINNER IS … 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 1 by Iona Mcnaughton the Winners So Far the Bird of the Year Competition Was Started As A

AND THE WINNER IS … 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 1 by Iona McNaughton The Winners So Far The Bird of the Year competition was started as a way of making people more interested in native 2005: Tūī 2010 New Zealand birds. Many of our native birds are 2006: Pīwakawaka – Fantail endangered, so if people know more about them, 2007: Riroriro – Grey warbler they can help to keep the birds safe. 2008: Kākāpō New Zealand native birds are given a “danger status”. 2009: Kiwi 2011 This shows how much danger they are in of becoming 2010: Kākāriki karaka – Orange-fronted parakeet extinct. The birds are either “doing OK”, “in some 2011: Pūkeko trouble”, or “in serious trouble”. Sadly, only about 2012: Kārearea – New Zealand falcon 20 percent of New Zealand native birds are 2013: Mohua – Yellowhead “doing OK”. 2014: Tara iti – Fairy tern 2012 Danger status This article has 2015: Kuaka – Bar-tailed godwit information about 2016: Kōkako some of the birds Kea In some Doing 2017: of the year – including trouble OK 2018: Kererū – New Zealand pigeon their danger status. 2013 In serious trouble 10 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 Bird of the Year 2006: Pīwakawaka – Fantail Bird of the Year 2005: Tūī Danger status Doing OK Danger status Doing OK Description Endemic Small body with a long tail that it can Description Endemic spread out like a fan A large bird (up to 32 centimetres long) About 16 centimetres long with shiny green-black feathers and a tu of white throat feathers What it eats Insects What it eats Insects. -

Waitaki Clutha

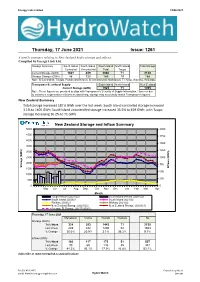

Energy Link Limited 18/06/2021 Waitaki Thursday, 17 June 2021 Issue: 1261 A weekly summary relating to New Zealand hydro storage and inflows. Compiled by Energy Link Ltd. Storage Summary South Island South Island South Island North Island Total Storage Controlled Uncontrolled Total Taupo Current Storage (GWh) 1601 459 2060 71 2130 Storage Change (GWh) 48 120 169 19 188 Note: SI Controlled; Tekapo, Pukaki and Hawea: SI Uncontrolled; Manapouri, Te Anau, Wanaka, Wakatipu Transpower Security of Supply South Island North Island New Zealand Current Storage (GWh) 1925 71 1995 Note: These figures are provided to align with Transpower's Security of Supply information. However due to variances in generation efficiencies and timing, storage may not exactly match Transpower's figures. New Zealand Summary Total storage increased 187.6 GWh over the last week. South Island controlled storage increased 3.1% to 1601 GWh; South Island uncontrolled storage increased 35.5% to 459 GWh; with Taupo storage increasing 36.2% to 71 GWh. New Zealand Storage and Inflow Summary 5000 2000 4500 1750 4000 1500 3500 1250 3000 2500 1000 Clutha 2000 750 Storage (GWh) Storage 1500 (GWh) Inflows 500 1000 250 500 0 0 May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Month Taupo Inflows (2021/22) South Island inflows (2021/22) South Island 2020/21 South Island 2021/22 Waikato 2020/21 Waikato 2021/22 New Zealand Storage (2021/22) New Zealand Storage (2020/21) Average SI Storage (16/17-20/21) Thursday, 17 June 2021 Manapouri Clutha Waitaki Waikato NZ Storage (GWh) This Week 324 293 1443 71 2130 Last Week 249 242 1400 52 1943 % Change 30.0% 20.9% 3.1% 36.2% 9.7% Inflow (GWh) This Week 166 117 173 51 507 Last Week 90 60 146 35 331 % Change 84.3% 96.1% 17.9% 46.8% 53.1% Subscribe at www.energylink.co.nz/publications Ph (03) 479 2475 Consultancy House Email: [email protected] Hydro Watch Dunedin Energy Link Limited 18/06/2021 Lake Levels and Outflows Catchment Lake Level Storage Outflow Outflow (m. -

Snow and Ice Research Group,!New Zealand

!"#$%&"'%()*%+*,*&-).%/-#012!3*$% 4*&5&"'%% % 6""0&5%7#-8,.#1% 9"$:"%;#'<*2%6#-&8:%=>%?##8%@:55&<*% A05B%C"'DA05B%E>.%CFGE% % H-#<-&II*% A0"*%CJ>.2%CFGE% % ! % % ?#D,1#",#-*'%KBL% % M.*%3&>:#"&5%(",>:>0>*%#N%7&>*-%&"'%6>I#,1.*-:)%+*,*&-).%O3(76P% 6">&-)>:)%+*,*&-).%?*">-*2%@:)>#-:&%9":Q*-,:>B%#N%7*55:"<>#"% =*-:':&"%R"*-<B% % % ! % 1 ! ! Welcome to SIRG2014. The following programme outlines what promises to be a great two days of presentations. All abstracts are appended in alphabetical order. At the back of this programme is an announcement for a public talk session scheduled for Thursday July 3rd. Also appended is a selection of excursions for Friday July 4th. We look forward to seeing you all at Unwin Lodge. – Huw Horgan and Brian Anderson. (Note that we will be distributing printed schedules for all participants but to avoid waste we will not be printing the full abstract booklet. A few printed copies will be available to share but if you would like your own copy please print it and bring it along.) ! % WEDNESDAY 12:00 LUNCH 13:20 WELCOME SESSION ONE 13:30 McColl, Sam WHEN THE ICE GIVES WAY: DEFORMATION OF ICE-BUTTRESSED SLOPES 13:45 Bell, Jeremy AVALANCHE RISK MITIGATION AND THE PERCEPTION OF HAZARDS 14:00 Anderson, Brian MEASURING GROUND DEFORMATION FROM TIME-LAPSE PHOTOGRAPHY – EXAMPLES FROM FRANZ JOSEF AND FOX GLACIERS 14:15 Still, Holly RESOLVING THE TEMPORAL AND SPATIAL VARIABILITY OF GLACIER SURFACE ALBEDO USING MODIS DATA 14:30 Short Introductions 15:00 BREAK SESSION TWO 15:30 Hulbe, Christina AS YOU LIKE IT: MEASUREMENTS -

Project River Recovery Bibliography

Project River Recovery bibliography 1991–July 2007 CANTERBURY SERIES 0208 Project River Recovery bibliography 1991 – JULY 2007 Project River Recovery Report 2007/02 Susan Anderson Department of Conservation, Private Bag, Twizel July 2007 Docdm-171819 - PRR Bibliography 2 INTRODUCTION Since its inception in 1991, Project River Recovery has undertaken or funded numerous research projects. The results of these investigations have been reported in various reports, theses, Department of Conservation publications, and scientific papers. Results of all significant research have been published, can be found through literature searches, and are widely available. Internal reports that do not warrant publication are held at the Twizel Te Manahuna Area Office and at the main Department of Conservation library in Wellington. All unpublished Project River Recovery reports produced since 1998 have been assigned report numbers. In addition to reports on original research, Project River Recovery has produced magazine articles and newspaper feature articles, various annual reports, progress reports, discussion documents, and plans. It has also commissioned some reports from consultants. This bibliography updates the bibliography compiled in 2000 (Sanders 2000) and lists all reports, theses, diplomas, Department of Conservation publications, and scientific papers that were produced or supported by Project River Recovery between 1991 and July 2007. It does not list brochures, posters, fact sheets, newsletters, abstracts for conference programmes, or minor magazine or newspaper articles. Docdm-171819 - PRR Bibliography 3 BIBLIOGRAPHY Adams, L.K. 1995: Reintroduction of juvenile black stilts to the wild. Unpublished MSc thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch. 108 p. Anderson, S.J. 2006: Proposal for black-fronted tern nest monitoring and predator trapping at the Ruataniwha Wetlands: 2006-2007 breeding season. -

Alternative Route to Twizel

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd GLENTANNER PARK CENTRE LAKE PUKAKI LAKE TEKAPO 54KM LANDSLIP CREEK ALTERNATIVE ROUTE TO TWIZEL TAKAPÕ LAKE TEKAPO MT JOHN OBSERVATORY BRAEMAR ROAD TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO Tekapo Powerhouse Rd TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km Hayman Rd Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS TEKAPO CANAL 9km 15km 24km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road 30km Lakeside Dr TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO 35km Tek Church of the apo-Twizel Rd Good Shepherd 8 MARY RANGES Dog Monument SALMONFA RM TO SALMON SHOP SH80 TEKAPO RIVER SH8 r s D 44km e r r C e i e Pi g n on SALMON SHOP n Roto Pl o RUATANIWHA i e a e P r r D CONSERVATION PARK o r A Scott Pond STARTING POINT PUKAKI CANAL SH8 Aorangi Cres 8 8 F Rd Lakeside airlie kapo -Te Car Park PUKAKI RIVER Lochinvar Ave Allan St Lilybank Rd Glen Lyon Rd r D n o P l Glen Lyon Rd ilt ollock P Andrew Don Dr am Old Glen Lyon Rd H N Pukaki Flats Track Rise TWIZEL 54km Murray Pl Rankin PUKAKI FLATS OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA SH8KEY: Fitness Easy Traffic Low 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL Onroad left onto Hayman Rd and ride to the Off-road trail 700 start of the off-road Trail on your right Skill Easy Grade 2 Information Centre 35km which follows the Lake Pukaki 600 Picnic Area shoreline. -

TS2-V6.0 11-Aoraki

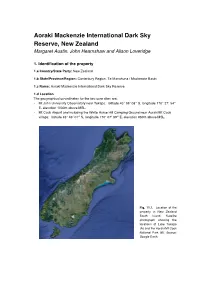

Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve, New Zealand Margaret Austin, John Hearnshaw and Alison Loveridge 1. Identification of the property 1.a Country/State Party: New Zealand 1.b State/Province/Region: Canterbury Region, Te Manahuna / Mackenzie Basin 1.c Name: Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 1.d Location The geographical co-ordinates for the two core sites are: • Mt John University Observatory near Tekapo: latitude 43° 59′ 08″ S, longitude 170° 27′ 54″ E, elevation 1030m above MSL. • Mt Cook Airport and including the White Horse Hill Camping Ground near Aoraki/Mt Cook village: latitude 43° 46′ 01″ S, longitude 170° 07′ 59″ E, elevation 650m above MSL. Fig. 11.1. Location of the property in New Zealand South Island. Satellite photograph showing the locations of Lake Tekapo (A) and the Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park (B). Source: Google Earth 232 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.e Maps and Plans See Figs. 11.2, 11.3 and 11.4. Fig. 11.2. Topographic map showing the primary core boundary defined by the 800m contour line Fig. 11.3. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boun- daries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 233 Fig. 11.4. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boundaries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary 234 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.f Area of the property Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve is located in the centre of the South Island of New Zealand, in the Canterbury Region, in the place known as Te Manahuna or the Mackenzie Basin (see Fig.