Aoraki Mt Cook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High-Precision 10Be Chronology of Moraines in the Southern Alps Indicates Synchronous Cooling in Antarctica and New Zealand 42,000 Years Ago ∗ Samuel E

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 405 (2014) 194–206 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl High-precision 10Be chronology of moraines in the Southern Alps indicates synchronous cooling in Antarctica and New Zealand 42,000 years ago ∗ Samuel E. Kelley a, ,1, Michael R. Kaplan b, Joerg M. Schaefer b, Bjørn G. Andersen c,2, David J.A. Barrell d, Aaron E. Putnam b, George H. Denton a, Roseanne Schwartz b, Robert C. Finkel e, Alice M. Doughty f a Department of Earth Sciences and Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, Orono, ME 04469, USA b Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory, Palisades, NY 10964, USA c Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway d GNS Science, Dunedin, New Zealand e Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, CA 94550, USA f Department of Earth Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03750, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Millennial-scale temperature variations in Antarctica during the period 80,000 to 18,000 years ago are Received 13 July 2013 known to anti-correlate broadly with winter-centric cold–warm episodes revealed in Greenland ice Received in revised form 22 July 2014 cores. However, the extent to which climate fluctuations in the Southern Hemisphere beat in time with Accepted 25 July 2014 Antarctica, rather than with the Northern Hemisphere, has proved a controversial question. In this study Available online 16 September 2014 we determine the ages of a prominent sequence of glacial moraines in New Zealand and use the results Editor: G.M. -

New Zealand 24 Days/23 Nights

Tour Code NZG 2018 New Zealand 24 days/23 nights An exceptional adventure awaits you at the other end of the world, discover the natural beauty of New Zealand. Nowhere else in the world will you find such a variety of landscapes: Glaciers, volcanic mountains, hot springs, lakes, Pacific coasts, virgin forests, snow-capped mountains and deep valleys opening onto fjords. New Zealand concentrates all the most beautiful European landscapes. A unique cycling experience! Day 1 and 2: Departure from Paris to Day 7 Moeraki – Naseby 49km Christchurch South Island In the morning, leave by bus to the Macraes The circuit runs along the Mt-Aspiring Flat, the largest active gold mine in New National Park. In clear weather you can see Depart for a long flight of approximately 24h00 Zealand. Since 1990, 1.8 million gold bars the snow-capped peaks glittering in the sun. to one of the furthest lands from Europe. have been extracted from this mine. We can A bus ride from the swamp forest of observe the area from a beautiful belvedere. Kahikatea to the Fox Glacier followed by a Day 3: Christchurch One of the most beautiful bike stages awaits short hike takes you to the foot of the glacier us. From 500m above sea level, it's time for Welcome to Christchurch, New Zealand's in the middle of the rainforest. a descent to the village of Hyde. The circuit second largest town, which stands above the follows the gold prospectors Otago Rail Trail, Pacific coast. Shortly after your arrival, you will Jour 12 Glacier le Fox Hotitika 67km a disused railway track dating from 1879, have the opportunity to visit the city and Port through tunnels and over viaducts with an Hill where you can admire the view of the impressive view of the Otago landscape. -

Phaedra Upton1, Rachel Skudder2 and the Mackenzie Basin Lakes

Using coupled models to place constraints on fluvial input into Lake Ohau, New Zealand Phaedra Upton1, Rachel Skudder2 and the Mackenzie Basin Lakes Team3 [email protected], 1GNS Science, 2Victoria University of Wellington, 3GNS Science + Otago University + Victoria University of Wellington 2004: no large storms 0 2000 kg/sec 1/1/10 daily rainfall Godley River modelled suspended sediment load Tasman River LakeTekapo 1/1/00 0 200 mm Lake Pukaki 1995: large summer storm 0 2000 kg/sec Hopkins River Box core #1 1/1/90 daily rainfall modelled suspended Lake Ohau Box core #2 Raymond Film Services sediment load Ahuriri River Figure 2: Lake Tekapo following a large rainfall event in its catchment. A sediment laden inflow plunges into the lake and leaves the surface waters clear. We use HydroTrend (Kettner and Syvitski 2008, Computers and 6 m core Daily Rainfall (mm) 0 200 mm Geoscience, 34) to calculate the overall sediment influx into the lake and 1/1/80 couple it to a conceptual model of how this sediment might be distributed 1969: large winter storm through the lake basin depending on the season to produce model cores. 0 2000 kg/sec 0 3 6 12 18 24km Figure 1: Located east of the main divide in the central Southern Alps, the Mackenzie Lakes; Ohau, Pukaki and Tekapo, occupy fault Figure 3: Map of Lake Ohau showing the location of the three cores we controlled glacial valleys and contain high resolution sedimentary compare our models to. daily rainfall records of the last ~17 ka. These sediments potentially contain a 1/1/70 modelled suspended record of climatic events and transitions, earthquakes along the Alpine sediment load Fault to the northwest, landscape response during and following deglaciation and recent human-influenced land use changes. -

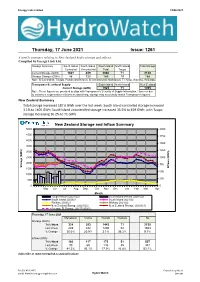

Waitaki Clutha

Energy Link Limited 18/06/2021 Waitaki Thursday, 17 June 2021 Issue: 1261 A weekly summary relating to New Zealand hydro storage and inflows. Compiled by Energy Link Ltd. Storage Summary South Island South Island South Island North Island Total Storage Controlled Uncontrolled Total Taupo Current Storage (GWh) 1601 459 2060 71 2130 Storage Change (GWh) 48 120 169 19 188 Note: SI Controlled; Tekapo, Pukaki and Hawea: SI Uncontrolled; Manapouri, Te Anau, Wanaka, Wakatipu Transpower Security of Supply South Island North Island New Zealand Current Storage (GWh) 1925 71 1995 Note: These figures are provided to align with Transpower's Security of Supply information. However due to variances in generation efficiencies and timing, storage may not exactly match Transpower's figures. New Zealand Summary Total storage increased 187.6 GWh over the last week. South Island controlled storage increased 3.1% to 1601 GWh; South Island uncontrolled storage increased 35.5% to 459 GWh; with Taupo storage increasing 36.2% to 71 GWh. New Zealand Storage and Inflow Summary 5000 2000 4500 1750 4000 1500 3500 1250 3000 2500 1000 Clutha 2000 750 Storage (GWh) Storage 1500 (GWh) Inflows 500 1000 250 500 0 0 May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr Month Taupo Inflows (2021/22) South Island inflows (2021/22) South Island 2020/21 South Island 2021/22 Waikato 2020/21 Waikato 2021/22 New Zealand Storage (2021/22) New Zealand Storage (2020/21) Average SI Storage (16/17-20/21) Thursday, 17 June 2021 Manapouri Clutha Waitaki Waikato NZ Storage (GWh) This Week 324 293 1443 71 2130 Last Week 249 242 1400 52 1943 % Change 30.0% 20.9% 3.1% 36.2% 9.7% Inflow (GWh) This Week 166 117 173 51 507 Last Week 90 60 146 35 331 % Change 84.3% 96.1% 17.9% 46.8% 53.1% Subscribe at www.energylink.co.nz/publications Ph (03) 479 2475 Consultancy House Email: [email protected] Hydro Watch Dunedin Energy Link Limited 18/06/2021 Lake Levels and Outflows Catchment Lake Level Storage Outflow Outflow (m. -

General Distribution and Characteristics of Active Faults and Folds in the Mackenzie District, South Canterbury D.J.A

General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Mackenzie District, South Canterbury D.J.A. Barrell D.T. Strong GNS Science Consultancy Report 2010/147 Environment Canterbury Report No. R10/44 June 2010 DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Limited (GNS Science) exclusively for and under contract to Environment Canterbury. Unless otherwise agreed in writing by GNS Science, GNS Science accepts no responsibility for any use of, or reliance on, any contents of this report by any person other than Environment Canterbury and shall not be liable to any person other than Environment Canterbury, on any ground, for any loss, damage or expense arising from such use or reliance. The data presented in this report are available to GNS Science for other use from June 2010 BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Barrell, D.J.A., Strong, D.T. 2010. General distribution and characteristics of active faults and folds in the Mackenzie District, South Canterbury. GNS Science Consultancy Report 2010/147. 22 p. © Environment Canterbury Report No. R10/44 ISBN 978-1-877574-18-4 Project Number: 440W1435 2010 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................II 1. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................1 2. INFORMATION SOURCES .........................................................................................2 3. GEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW -

Lake Ohau Lodge to Omarama

SH80 km SECTION 4: Lake Ohau Lodge to Omarama 40 SH8 FITNESS: Intermediate SKILL:Intermediate TRAFFIC: Low GRADE: 3 PUKAKI CANAL 4 LAKE OHAU LODGE Ben Ohau Rd Glen Lyon Rd SKIFIELD CREEK Glen Lyon Rd BEN OHAU Manuka Tce LAKE OHAU Old Glen Lyon Rd PARSONS CREEK TWIZEL 3 Lake Ohau Max Smith Dr SAWYERS CREEK Rd Glen LyonOHAU Road CANAL FREEHOLD CREEK LAKE OHAU VILLAGE OHAU RIVER OHAU WEIR FLOOD ROUTE Tambrae Track LAKE RUATANIWHA LAKE MIDDLETON SH8 OHAU WEIR Lake Ohau Track Maori Swamp High Point Lake Ohau Rd HISTORIC WOOLSHED Quailburn Rd N LEVEL 1000 BENMORE RANGE 800 SH8 AORAKI/MOUNT COOK AORAKI/MOUNT LAKE OHAU LODGE LAKE OHAU 600 BRAEMAR STATION TWIZEL OMARAMA 400 OTEMATATA KUROW Quailburn Rd 200 DUNTROON OAMARU 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 260 280 300 Henburn Rd KEY: Onroad Off-road trail Ohau Weir flood route Picnic Area Prohibition Rd AHURIRI RIVER 0 1 2 3 4 5km CLAY CLIFFS Scale OMARAMA 5 www.alps2ocean.com SH83 SH8 Map current as of 24/9/13 Starting from the Lake Ohau Lodge descent to Quailburn Road [18.3km]. to see the Clay Cliffs (14km return). driveway, the trail traverses the lower From the Quailburn Road intersection you When Quailburn Road meets the slopes of the Ruataniwha Conservation can detour 2km to the historic woolshed highway [35.6km], the off-road trail winds Park, with stunning views back across the at the end of Quailburn Road (where alongside below the highway edge. basin to the Benmore Range. -

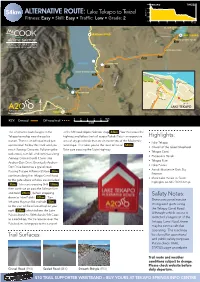

Alternative Route to Twizel

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd GLENTANNER PARK CENTRE LAKE PUKAKI LAKE TEKAPO 54KM LANDSLIP CREEK ALTERNATIVE ROUTE TO TWIZEL TAKAPÕ LAKE TEKAPO MT JOHN OBSERVATORY BRAEMAR ROAD TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO Tekapo Powerhouse Rd TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km Hayman Rd Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS TEKAPO CANAL 9km 15km 24km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road 30km Lakeside Dr TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO 35km Tek Church of the apo-Twizel Rd Good Shepherd 8 MARY RANGES Dog Monument SALMONFA RM TO SALMON SHOP SH80 TEKAPO RIVER SH8 r s D 44km e r r C e i e Pi g n on SALMON SHOP n Roto Pl o RUATANIWHA i e a e P r r D CONSERVATION PARK o r A Scott Pond STARTING POINT PUKAKI CANAL SH8 Aorangi Cres 8 8 F Rd Lakeside airlie kapo -Te Car Park PUKAKI RIVER Lochinvar Ave Allan St Lilybank Rd Glen Lyon Rd r D n o P l Glen Lyon Rd ilt ollock P Andrew Don Dr am Old Glen Lyon Rd H N Pukaki Flats Track Rise TWIZEL 54km Murray Pl Rankin PUKAKI FLATS OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA SH8KEY: Fitness Easy Traffic Low 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL Onroad left onto Hayman Rd and ride to the Off-road trail 700 start of the off-road Trail on your right Skill Easy Grade 2 Information Centre 35km which follows the Lake Pukaki 600 Picnic Area shoreline. -

Canterbury Conservation Management Strategy

Canterbury Conservation Management Strategy Volume 1 Published by Department of Conservation/Te Papa Atawhai Private Bag 4715 Christchurch New Zealand First published 2000 Canterbury Conservation Management Planning Series No. 10 ISSN: 1171-5391-10 ISBN: 0-478-01991-2 Foreword Canterbury is rich in its variety of indigenous plants and animals, its historic heritage and relics, and its landscapes. Its physical features are dramatic, ranging from the majestic Southern Alps to the Canterbury Plains, from forested foothills to rocky coastlines and sandy beaches. These features also provide a wealth of recreational opportunities. The Department of Conservation’s Canterbury Conservancy is responsible for some 1293 units of land, and for the protection of important natural resources generally. To help manage these resources and activities the Conservancy, in consultation with the then North Canterbury and Aoraki Conservation Boards, has prepared a Conservation Management Strategy (CMS). The CMS sets out the management directions the Conservancy will take for the next ten years, the objectives it wants to achieve and the means by which it will achieve these. The draft CMS was released for public comment on 18 November 1995. Submissions closed on 1 April 1996, and 174 were received. Public oral submissions were heard in May and June of 1996. Consultation with Ngäi Tahu Papatipu Rünanga occurred from July to December 1996, and with Te Rünanga o Ngäi Tahu from July 1996 to May 1997. A summary of submissions and a decision schedule indicating the extent of acceptance of all submissions was prepared and given full consideration in revising the draft CMS. The revised draft CMS and summary of submissions was presented to the Conservation Boards for their consideration. -

Lake Tekapo to Twizel Highlights

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL 700 54km ALTERNATIVEGLENTANNER PARK CENTRE ROUTE: Lake Tekapo to Twizel 600 LANDSLIP CREEK ELEVATION Fitness: Easy • Skill: Easy • Traffic: Low • Grade: 2 500 400 KM LAKE PUKAKI 0 10 20 30 40 50 MT JOHN OBSERVATORY LAKE TEKAPO BRAEMAR ROAD Tekapo Powerhouse Rd LAKE TEKAPO TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km TRAIL GUARDIAN Hayman Rd SALMON FARM TO SALMON SHOP Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS 9km TEKAPO CANAL 15km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM 24km TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road LAKE TEKAPO 30km Lakeside Dr Te kapo-Twizel Rd Church of the 8 Good Shepherd Dog Monument MARY RANGES SH80 35km r s D TEKAPO RIVERe SH8 r r 44km C e i e Pi g n on n Roto Pl o i e a e P SALMON SHOP r r D o r A Scott Pond Aorangi Cres 8 PUKAKI CANAL SH8 F Rd airlie-Tekapo PUKAKI RIVER Allan St Glen Lyon Rd Glen Lyon Rd LAKE TEKAPO Andrew Don Dr Old Glen Lyon Rd Pukaki Flats Track Murray Pl TWIZEL PUKAKI FLATS Mapwww.alps2ocean.com current as of 28/7/17 N 54km OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA 0 1 2 3 4 5km KEY: Onroad Off-road trail SH8 Scale The alternative route begins in the at the Mt Cook Alpine Salmon shop 44km . You then cross the Tekapo township near the police highway and follow the trail across Pukaki Flats – an expansive Highlights: station. -

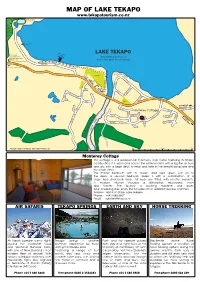

Map of Lake Tekapo

MAP OF LAKE TEKAPO www.tekapotourism.co.nz Tekapo Springs and Winter Park Mt John walkway. Access to Earth and Sky and Astro cafe Boat ramp Power station LAKE TEKAPO Earth and Sky intake Observatory 7.6km KEEP CLEAR www.tekapotourism.co.nz Mackenzie Alpine Horse Trekking 1.5km Your online guide to Lake Tekapo (via Godley Peaks Road) STAT SIDE D E LAKE RIVE HIG Air Safaris airport 1.5km HW AY 8 Boat ramp CHURCH OF THE GOOD SHEPHERD DOMAIN DOG STATUE V I D L R LA IV G R E E E C E E N N T O R I E P E ROT ZI O N S E EA K D A LY C D ’AR O A L C R M A H IA A B C D N P B R G I IV M S E I A W H AL C STATE TE U HIGH R B A WAY LA C E CK RES PARK B 8 B I L L S A Roundhill Ski A P M E S Area 32km S E A AD V LL RO I A LILYBANK L N S LO N R T CHI D J Monterey Cottage E V ER E V E I U S R A N T D V H N E L E E O HAY N P N A R SC BARBAR Mt Dobson D OTT O P U D O K T H L C S L LO E S W I Ski Area 43km T O M T Y A P E H W E R E R R VE O RISE D I ’ IN N K N R MURRA AN Y R PLACE E A B I L U L R O N P ET A T K E T Copyright Tekapo Tourism Ltd. -

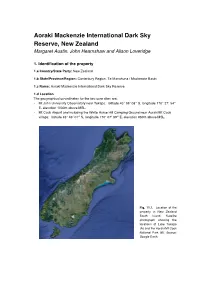

TS2-V6.0 11-Aoraki

Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve, New Zealand Margaret Austin, John Hearnshaw and Alison Loveridge 1. Identification of the property 1.a Country/State Party: New Zealand 1.b State/Province/Region: Canterbury Region, Te Manahuna / Mackenzie Basin 1.c Name: Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 1.d Location The geographical co-ordinates for the two core sites are: • Mt John University Observatory near Tekapo: latitude 43° 59′ 08″ S, longitude 170° 27′ 54″ E, elevation 1030m above MSL. • Mt Cook Airport and including the White Horse Hill Camping Ground near Aoraki/Mt Cook village: latitude 43° 46′ 01″ S, longitude 170° 07′ 59″ E, elevation 650m above MSL. Fig. 11.1. Location of the property in New Zealand South Island. Satellite photograph showing the locations of Lake Tekapo (A) and the Aoraki/Mt Cook National Park (B). Source: Google Earth 232 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.e Maps and Plans See Figs. 11.2, 11.3 and 11.4. Fig. 11.2. Topographic map showing the primary core boundary defined by the 800m contour line Fig. 11.3. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boun- daries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve 233 Fig. 11.4. Map showing the boundaries of the secondary core at Mt Cook Airport. The boundaries are clearly defined by State Highway 80, Tasman Valley Rd, and Mt Cook National Park’s southern boundary 234 Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy 1.f Area of the property Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve is located in the centre of the South Island of New Zealand, in the Canterbury Region, in the place known as Te Manahuna or the Mackenzie Basin (see Fig. -

Brochure on Freedom Camping

What is a self-contained vehicle? A self-contained vehicle has been designed and built MACKENZIE for the purpose of camping. The vehicle’s facilities meet all of your bathroom and toilet needs for a District Council minimum of three days in a row, without the need for external services, or the need to discharge waste in public facilities or into the environment. The vehicle complies with NZ standards and has a toilet facility that is readily usable. Need to stay in a designated Self-contained camping doesn’t include: camping ground? • The need to use portable toilets that aren’t located in a fully private facility. Fairlie Holiday Park 03 685 8375 • Undertaking toileting and bathroom needs in the Lake Tekapo Motels and 0800 853 853 natural environment. Holiday Park Twizel Holiday Park 03 435 0507 We want to protect our community and our environment. If you have a vehicle that isn’t self- Lake Ruataniwha Holiday Park 03 435 0613 contained, we ask that you stay in a designated and Motels camping ground. There are also camping sites at Lake Alexandrina south end and at the Lake McGregor/Lake Alexandrina outlet. Remember, freedom campers must leave nothing, take all of their waste with them and mustn’t do any CamperMate is a free New Zealand damage to the area they use. travel app that helps freedom campers Please be a responsible freedom camper. If you camp find essential services nearby. in areas where freedom camping isn’t allowed, don’t have a fully self-contained vehicle, or don’t follow our other rules, you may have to pay a fine or be asked to move on.