Canterbury Conservation Management Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 2018 Climate Summary Information

New Zealand Climate Summary: September 2018 Issued: 3 October 2018 A wet start to spring for some but dry for most Temperature Mean temperatures for September were near average (i.e. -0.50 to +0.50°C) across most of the country. Below average mean temperatures (i.e. -0.51 to -1.20°C) were restricted to eastern locations in Canterbury and Marlborough, as well as part of Northland, and other isolated patches in the North Island. Rainfall Rainfall was above normal (i.e. 120-149% of normal) to well above normal (i.e. >149% of normal) for eastern parts of the North Island as well as around Otago and Southland. Northland and Wellington experienced near normal rainfall totals (i.e. 80- 119% of normal) while much of the country experienced below normal (50-79% of normal) or well below normal (<50% of normal) rainfall levels. Soil Moisture As of 1 October 2018, soil moisture levels were above normal for the time of year for much of Otago, particularly toward the coast, as well as around coastal Gisborne. Drier than normal soil moistures were present from Nelson through to northern Canterbury and through much of the central and southern North Island. Soil moisture levels were generally near normal for the time of year across the rest of the country. Click on the link to jump to the information you require: Overview Rainfall Temperature September climate in the six main centres Highlights and extreme events Overview For the month as whole, September mean sea level pressure was lower than normal over and to the northeast of the North Island and higher than normal over and to the west of the South Island, resulting in more southeasterly winds than normal over the country. -

New Zealand 24 Days/23 Nights

Tour Code NZG 2018 New Zealand 24 days/23 nights An exceptional adventure awaits you at the other end of the world, discover the natural beauty of New Zealand. Nowhere else in the world will you find such a variety of landscapes: Glaciers, volcanic mountains, hot springs, lakes, Pacific coasts, virgin forests, snow-capped mountains and deep valleys opening onto fjords. New Zealand concentrates all the most beautiful European landscapes. A unique cycling experience! Day 1 and 2: Departure from Paris to Day 7 Moeraki – Naseby 49km Christchurch South Island In the morning, leave by bus to the Macraes The circuit runs along the Mt-Aspiring Flat, the largest active gold mine in New National Park. In clear weather you can see Depart for a long flight of approximately 24h00 Zealand. Since 1990, 1.8 million gold bars the snow-capped peaks glittering in the sun. to one of the furthest lands from Europe. have been extracted from this mine. We can A bus ride from the swamp forest of observe the area from a beautiful belvedere. Kahikatea to the Fox Glacier followed by a Day 3: Christchurch One of the most beautiful bike stages awaits short hike takes you to the foot of the glacier us. From 500m above sea level, it's time for Welcome to Christchurch, New Zealand's in the middle of the rainforest. a descent to the village of Hyde. The circuit second largest town, which stands above the follows the gold prospectors Otago Rail Trail, Pacific coast. Shortly after your arrival, you will Jour 12 Glacier le Fox Hotitika 67km a disused railway track dating from 1879, have the opportunity to visit the city and Port through tunnels and over viaducts with an Hill where you can admire the view of the impressive view of the Otago landscape. -

Lake Ohau Lodge to Omarama

SH80 km SECTION 4: Lake Ohau Lodge to Omarama 40 SH8 FITNESS: Intermediate SKILL:Intermediate TRAFFIC: Low GRADE: 3 PUKAKI CANAL 4 LAKE OHAU LODGE Ben Ohau Rd Glen Lyon Rd SKIFIELD CREEK Glen Lyon Rd BEN OHAU Manuka Tce LAKE OHAU Old Glen Lyon Rd PARSONS CREEK TWIZEL 3 Lake Ohau Max Smith Dr SAWYERS CREEK Rd Glen LyonOHAU Road CANAL FREEHOLD CREEK LAKE OHAU VILLAGE OHAU RIVER OHAU WEIR FLOOD ROUTE Tambrae Track LAKE RUATANIWHA LAKE MIDDLETON SH8 OHAU WEIR Lake Ohau Track Maori Swamp High Point Lake Ohau Rd HISTORIC WOOLSHED Quailburn Rd N LEVEL 1000 BENMORE RANGE 800 SH8 AORAKI/MOUNT COOK AORAKI/MOUNT LAKE OHAU LODGE LAKE OHAU 600 BRAEMAR STATION TWIZEL OMARAMA 400 OTEMATATA KUROW Quailburn Rd 200 DUNTROON OAMARU 0 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160 180 200 220 240 260 280 300 Henburn Rd KEY: Onroad Off-road trail Ohau Weir flood route Picnic Area Prohibition Rd AHURIRI RIVER 0 1 2 3 4 5km CLAY CLIFFS Scale OMARAMA 5 www.alps2ocean.com SH83 SH8 Map current as of 24/9/13 Starting from the Lake Ohau Lodge descent to Quailburn Road [18.3km]. to see the Clay Cliffs (14km return). driveway, the trail traverses the lower From the Quailburn Road intersection you When Quailburn Road meets the slopes of the Ruataniwha Conservation can detour 2km to the historic woolshed highway [35.6km], the off-road trail winds Park, with stunning views back across the at the end of Quailburn Road (where alongside below the highway edge. basin to the Benmore Range. -

Fred M. Springer Collection

Fred M. Springer Collection Finding Aid to the Collection at the Center for Railroad Photography & Art Prepared by Jordan Radke Last updated: 10/07/15 Collection Summary Title: Fred M. Springer Collection Span Dates: 1950 – 2006 Bulk Dates: 1985 – 2004 Creator: Springer, Fred M., 1928 – 2012 Extent: 15 archival boxes (Approximately 50,000 color slides); 15 linear feet Language: English Repository: Center for Railroad Photography & Art, Madison, WI Abstract: Color slides by Fred M. Springer, from his collection of approximately 50,000 photographs, which he and his wife, Dale, donated to the Center in 2012. The collection spans more than fifty years, six continents, thirty countries, and forty states. Major areas of focus include steam in both regular service and on tourist and scenic railroads, structures including depots and engine terminals, and railroads in the landscape. Selected Search Terms Country: Argentina Mexico Australia Netherlands Austria New Zealand Belgium Norway Bolivia Paraguay Brazil Poland Canada South Africa Chile Spain Czech Republic Sweden Denmark Switzerland Ecuador Syria France United Kingdom Germany United States Guatemala Zambia Italy Zimbabwe Jordan State: Alabama California Alaska Colorado Arizona Delaware Arkansas Florida Fred M. Springer Collection 2 Georgia New Mexico Illinois New York Indiana North Carolina Iowa North Dakota Kansas Ohio Kentucky Oklahoma Louisiana Pennsylvania Maine Tennessee Massachusetts Texas Michigan Utah Minnesota Vermont Mississippi Virginia Missouri Washington Montana West Virginia -

Recco® Detectors Worldwide

RECCO® DETECTORS WORLDWIDE ANDORRA Krimml, Salzburg Aflenz, ÖBRD Steiermark Krippenstein/Obertraun, Aigen im Ennstal, ÖBRD Steiermark Arcalis Oberösterreich Alpbach, ÖBRD Tirol Arinsal Kössen, Tirol Althofen-Hemmaland, ÖBRD Grau Roig Lech, Tirol Kärnten Pas de la Casa Leogang, Salzburg Altausee, ÖBRD Steiermark Soldeu Loser-Sandling, Steiermark Altenmarkt, ÖBRD Salzburg Mayrhofen (Zillertal), Tirol Axams, ÖBRD Tirol HELICOPTER BASES & SAR Mellau, Vorarlberg Bad Hofgastein, ÖBRD Salzburg BOMBERS Murau/Kreischberg, Steiermark Bischofshofen, ÖBRD Salzburg Andorra La Vella Mölltaler Gletscher, Kärnten Bludenz, ÖBRD Vorarlberg Nassfeld-Hermagor, Kärnten Eisenerz, ÖBRD Steiermark ARGENTINA Nauders am Reschenpass, Tirol Flachau, ÖBRD Salzburg Bariloche Nordkette Innsbruck, Tirol Fragant, ÖBRD Kärnten La Hoya Obergurgl/Hochgurgl, Tirol Fulpmes/Schlick, ÖBRD Tirol Las Lenas Pitztaler Gletscher-Riffelsee, Tirol Fusch, ÖBRD Salzburg Penitentes Planneralm, Steiermark Galtür, ÖBRD Tirol Präbichl, Steiermark Gaschurn, ÖBRD Vorarlberg AUSTRALIA Rauris, Salzburg Gesäuse, Admont, ÖBRD Steiermark Riesneralm, Steiermark Golling, ÖBRD Salzburg Mount Hotham, Victoria Saalbach-Hinterglemm, Salzburg Gries/Sellrain, ÖBRD Tirol Scheffau-Wilder Kaiser, Tirol Gröbming, ÖBRD Steiermark Schiarena Präbichl, Steiermark Heiligenblut, ÖBRD Kärnten AUSTRIA Schladming, Steiermark Judenburg, ÖBRD Steiermark Aberg Maria Alm, Salzburg Schoppernau, Vorarlberg Kaltenbach Hochzillertal, ÖBRD Tirol Achenkirch Christlum, Tirol Schönberg-Lachtal, Steiermark Kaprun, ÖBRD Salzburg -

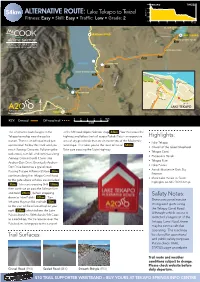

Lake Tekapo to Twizel Highlights

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL 700 54km ALTERNATIVEGLENTANNER PARK CENTRE ROUTE: Lake Tekapo to Twizel 600 LANDSLIP CREEK ELEVATION Fitness: Easy • Skill: Easy • Traffic: Low • Grade: 2 500 400 KM LAKE PUKAKI 0 10 20 30 40 50 MT JOHN OBSERVATORY LAKE TEKAPO BRAEMAR ROAD Tekapo Powerhouse Rd LAKE TEKAPO TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km TRAIL GUARDIAN Hayman Rd SALMON FARM TO SALMON SHOP Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS 9km TEKAPO CANAL 15km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM 24km TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road LAKE TEKAPO 30km Lakeside Dr Te kapo-Twizel Rd Church of the 8 Good Shepherd Dog Monument MARY RANGES SH80 35km r s D TEKAPO RIVERe SH8 r r 44km C e i e Pi g n on n Roto Pl o i e a e P SALMON SHOP r r D o r A Scott Pond Aorangi Cres 8 PUKAKI CANAL SH8 F Rd airlie-Tekapo PUKAKI RIVER Allan St Glen Lyon Rd Glen Lyon Rd LAKE TEKAPO Andrew Don Dr Old Glen Lyon Rd Pukaki Flats Track Murray Pl TWIZEL PUKAKI FLATS Mapwww.alps2ocean.com current as of 28/7/17 N 54km OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA 0 1 2 3 4 5km KEY: Onroad Off-road trail SH8 Scale The alternative route begins in the at the Mt Cook Alpine Salmon shop 44km . You then cross the Tekapo township near the police highway and follow the trail across Pukaki Flats – an expansive Highlights: station. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABOUT US (i) FACTS ABOUT DVDs / POSTAGE RATES (ii) LOOKING AFTER YOUR DVDs (iii) Greg Scholl 1 Pentrex (Incl.Pentrex Movies) 9 ‘Big E’ 32 General 36 Electric 39 Interurban 40 Diesel 41 Steam 63 Modelling (Incl. Allen Keller) 78 Railway Productions 80 Valhalla Video Productions 83 Series 87 Steam Media 92 Channel 5 Productions 94 Video 125 97 United Kindgom ~ General 101 European 103 New Zealand 106 Merchandising Items (CDs / Atlases) 110 WORLD TRANSPORT DVD CATALOGUE 112 EXTRA BOARD (Payment Details / Producer Codes) 113 ABOUT US PAYMENT METHODS & SHIPPING CHARGES You can pay for your order via VISA or MASTER CARD, Cheque or Australian Money Order. Please make Cheques and Australian Money Orders payable to Train Pictures. International orders please pay by Credit Card only. By submitting this order you are agreeing to all the terms and conditions of trading with Train Pictures. Terms and conditions are available on the Train Pictures website or via post upon request. We will not take responsibility for any lost or damaged shipments using Standard or International P&H. We highly recommend Registered or Express Post services. If your in any doubt about calculating the P&H shipping charges please drop us a line via phone or send an email. We would love to hear from you. Standard P&H shipping via Australia Post is $3.30/1, $5.50/2, $6.60/3, $7.70/4 & $8.80 for 5-12 items. Registered P&H is available please add $2.50 to your standard P&H postal charge. -

Aoraki Mt Cook

Anna Thompson: Aoraki/Mt Cook – cultural icon or tourist “object” The natural areas of New Zealand, particularly national parks, are a key attraction for domestic and international visitors who venture there for a variety of recreation and leisure purposes. This paper discusses the complex cultural values and timeless quality of an iconic landmark - Aoraki/Mt Cook – which is located within the ever-changing Mackenzie Basin. It explores the various human values for the mountain and the surrounding regional landscape which has become iconic in its own right. The landscape has economic, environmental, scientific and social significance with intangible heritage values and connotations of sacred and sublime experiences of place. The paper considers Aoraki/Mt Cook as a ‘wilderness’ region that is also a focal point not only for local inhabitants but also for travellers sightseeing and recreating in the area. The paper also explores how cultural values for the mountain are interpreted to visitors in an attempt to convey a sense of ‘place’. Finally the Mackenzie Basin is discussed as a special ‘in-between’ place – that should be considered significant in its own right and not just as a ‘foreground’ or ‘frame’ for viewing the Southern Alps and Aoraki/Mt Cook itself. The Mackenzie has aesthetic scenic qualities that need careful management of activities such as recent attempts to establish industrialised, dairy factory farming (which does not complement more sustainable economic and social development in the region). Sympathetic projects such as the Nga Haerenga (Ocean to the Alps) cycle way are also under development to encourage activity within the landscape – in conflict with the dairying and other activities that impact negatively on the natural resources of the region.1 Introduction – cultural values for landscape and ‘place’ Aotearoa New Zealand is regarded by many as a ‘young country’ – the last indigenous populated country to be colonised by European cultures. -

7707 Ashburton Glassworks

7707 Ashburton Glassworks (Former) 8 Glassworks Road and Bremners Road ASHBURTON Ashburton District Council 270 Longbeach Station Homestead Longbeach Road ASHBURTON Ashburton District Council 284 Church of the Holy Name (Catholic) Sealey Street ASHBURTON Ashburton District Council 7593 Pipe Shed South Belt METHVEN Ashburton District Council 7753 Symonds Street Cemetery 72 Karangahape Road AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 94 Auckland War Memorial Museum 28 Domain Drive Auckland Domain AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 122 Cenotaph Domain Drive Auckland Domain AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 124 Domain Wintergardens Domain Drive Auckland Domain AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 4478 John Logan Campbell Monument 6 Campbell Cresent Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 2623 Clifton 11 Castle Drive Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 18 Highwic 40 Gillies Avenue Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 7276 Rocklands Hall 187 Gillies Avenue Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 4471 Auckland Grammar School (Main Block) 87 Mountain Road Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 4472 War Memorial, Auckland Grammar School 87 Mountain Road Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 116 St Andrew's Church (Anglican) 100 St Andrew's Road Epsom AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 7664 Auckland Municipal Destructor and Depot (Former) 210‐218 Victoria Street West and Union and Drake Streets Freemans Bay AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 98 Church of the Holy Sepulchre and Hall 71 Khyber Pass Road and Burleigh Street Grafton AUCKLAND Auckland City Council 5440 Cotswalds House 37 Wairakei -

Journal Issue # 149

NOV 2015 JOURNAL ISSUE # 149 PUBLISHED BY FEDERATION OF RAIL ORGANISATIONS NZ INC : P O BOX 140, DUNEDIN 9054 PLEASE SEND CONTRIBUTIONS TO EDITOR, SCOTT OSMOND, BY E-MAIL : [email protected] IN THIS Steam Coal Supplies 1 News from our Members 6 ISSUE Health & Safety Legislation 2 Steam Incorporated South Island Tour 10 Level Crossing Vehicle Complaints 4 Members Classifieds 13 Tokomaru Steam Museum Sale 4 Picture of the Month 14 STEAM COAL SUPPLIES Ian Tibbles has supplied the following information regarding steam coal supplies. Knowing the precarious state of suitable steam coal which faces those operating large or network locos, I thought the attached article from the Grey Star, 6 Nov 2015, should be circulated amongst members who may need to contact their local supplier as regards a future supply. With the apparent demise of the Cascade Mine the preferred and often only suitable steam coal, the choices to my knowledge are limited to; Strongman - very limited production, Redale, Reefton - a limited scale opencast operation with equally limited future and Garveys Ck, Reefton - well known for destroying grates. There may be some medium heat coals from couple of small mines in the Reefton area and of course the well known Mai Mai lignite and that is it. Any members are welcome to contact me but best they contact their favourite supplier with a copy of the newspaper cutting. CORRECTION—AGAIN!! Dave Hinman, FRONZ Tramway Convenor, has unfortunately has his e-mail address printed incorrectly twice in Jour- nal. My sincere apologies Dave. The correct e-mail for Dave [email protected]. -

Journal Issue # 206

DEC 2020 JOURNAL ISSUE # 206 PUBLISHED BY FEDERATION OF RAIL ORGANISATIONS NZ INC : PLEASE SEND CONTRIBUTIONS TO EDITOR, SCOTT OSMOND, BY E-MAIL : [email protected] FRONZ Update 1 IN THIS News From Our Members 2 ISSUE Future Mainline Excursions 12 Picture of the Month 13 FRONZ UPDATE The FRONZ Executive missed our planned Zoom meeting for December due to unavailability of sev- eral members but will be catching up as soon as possible. Issues of note this month: • We have received several queries from members questioning the unexpectedly high accounts received from the Rail Regulator, Waka Kotahi NZTA, for Safety Assessment work recently. We will be approaching Waka Kotahi to discuss this issue further. • Waka Kotahi have just produced an annual review document which can be found at Signal-a-year-in-rail-safety- 2019-20. This is a well-rounded document and has had input by FRONZ. It also highlights, in the statistical sec- tions, how significant the role played by heritage operators is in the New Zealand rail passenger scene. • Many readers will have seen circulated through various social media and e-mail, the document that Kiwirail pro- duced to brief the new Minister of Transport. Unsurprisingly it does not include heritage operators in their list of “stakeholders” or anywhere in the document. • Following the cabinet appointments announced by the Prime Minister, FRONZ has approached the new Minister of Transport for an opportunity to discuss our role with him and will be doing so as soon as we can arrange an appointment. In our regular discussions with the Ministry of Transport it has been suggested we should prepare a briefing paper for him prior to our meeting, as the MOT will do also. -

ICOMOS New Zealandnews

ICOMOS New Zealand NEWS Te kawerongo hiko o te mana o nga pouwhenua o te ao 8 September 2010 ISSN 0113-2237 www.icomos.org.nz Softly does it in the city at risk COMOS NZ is urging the Christchurch City Council to take I particular care in assessing damage to its heritage buildings, following Saturday’s devastating earthquake and to learn from the lessons of the 2007 Gisborne earthquake where a number of damaged heritage buildings were demolished when expert advice could have saved them. ICOMOS New Zealand takes the view that engineering advice that is sympathetic to heritage values is important and that the top-ranked heritage buildings that have come through the quake with only moderate damage are testaments to good engineering interventions of the last decade or so. As the diggers move in to Christchurch streets, Dr Ian Lochhead, (left) a board member of ICOMOS and Associate Professor of architectural history at the University of Canterbury urges the earthquake cleanup authorities to seek advice before making decisions on the fates of buildings. “Many buildings that look in a grim state can, in fact, be saved. There should be no precipitous clearing or removal of heritage buildings or structures, and priority should be given to stabilisation, repair, and reconstruction.” He said “Christchurch has a rich Damage to the octagonal room makes it region. ICOMOS considers undue stock of architecturally significant the second time round for Cranmer haste to get back to normal should buildings. The city‟s built heritage is Square’s 1875 former Normal School, now not be allowed to compromise the Cranmer Court, which lost two towers an important part of the city‟s long-term objectives of repair and identity and attraction, and ICOMOS after an earthquake in 1928.