The Battle of Valcour Island: an American Navy on Lake Champlain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Valcour_Island Coordinates: 44°36′37.84″N 73°25′49.39″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Battle of Valcour Island Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Part of the American Revolutionary War Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley. The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Royal Savage is shown run aground and burning, Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after while British ships fire on her (watercolor by British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the unknown artist, ca. 1925) summer of 1776 fortifying those forts, and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet Date October 11, 1776 already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man Location near Valcour Bay, Lake Champlain, army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry Town of Peru / Town of Plattsburgh, it on the lake. -

The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold 1 National Museum of American History

The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold 1 National Museum of American History The Time Trial of Benedict Arnold Purpose By debating the legacy of Benedict Arnold, students will build reasoning and critical thinking skills and an understanding of the complexity of historical events and historical memory. Program Summary In this presentation, offered as a public program at the National Museum of American History from December 2010-April 2011, an actor portrays a fictionalized Benedict Arnold, hero and villain of the American Revolution. Arnold, in dialogue with an audience that is facilitated by an arbiter, discusses his notable actions at the Battle of Saratoga and at Valcour Island, as well as his decision to sell the plans for West Point to the British. At the conclusion of the program, audience members consider how history should remember Arnold, as a traitor, or as a hero. This set of materials is designed to provide you an opportunity to have a similar debate with your students. Included in this resource set are a full video of the program, to be used as preparation for the classroom activity, and Arnold’s conversation with the audience divided by theme, to be used with the resources offered below for your own Time Trial of Benedict Arnold. A full version of the program is available here. [https://vimeo.com/129257467] Grade levels 5-8 Time Three 45 minute periods National Standards National Center for History in the Schools: United States History Standards; Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s); Standard 2: The impact of the American Revolution on politics, economy, and society Common Core Standards for Literacy in History and Social Studies: Speaking and Listening Standards Comprehension and Collaboration, standard 1: Grades 6-8: Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher- led) with diverse partners on grade level topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly. -

Naval Documents of the American Revolution

Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 6 AMERICAN THEATRE: Aug. 1, 1776–Oct. 31, 1776 EUROPEAN THEATRE: May 26, 1776–Oct. 5, 1776 Part 1 of 8 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1972 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2012 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. NAVAL DOCUMENTS OF The American Revolution Continental Gunboat Philadelphia. NAVAL DOCUMENTS OF The American Revolution VOLUME 6 AMERICAN THEATRE: Aug. 1, 1776-Oct. 31, 1776 EUROPEAN THEATRE: May 26, 1776-Oct. 5, 1776 WILLIAM JAMES MORGAN, Editor With a Foreword by PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON And an Introduction by VICE ADMIRAL EDWIN B. HOOPER, USN (Ret.) Director of Naval History NAVAL HISTORY DIVISION DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY WASHINGTON: 1972 I LC. Card No. 64-60087 I For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $18.40 domestic postpaid or $17.25 GPO Bookstore Each volume of this series is a reminder of the key role played by the late William Bell Clark, initial editor. Drawing upon his deep knowledge of the Navy in the American Revolution, his initial selections and arrangements of materials compiled over a devoted lifetime provided a framework on which subsequent efforts have continued to build. SECRETARY OF THE NAVY'S ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON NAVAL HISTORY James P. Baxter, I11 (Emeritus) Jim Dan Hill Samuel Flagg Bemis (Emeritus) Elmer L. Kayser Francis L. Berkeley, Jr. John Haskell Kemble Julian P. Boyd Leonard W. Labaree Marion V. -

030321 VLP Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga readies for new season LEE MANCHESTER, Lake Placid News TICONDEROGA — As countered a band of Mohawk Iro- name brought the eastern foothills American forces prepared this quois warriors, setting off the first of the Adirondack Mountains into week for a new war against Iraq, battle associated with the Euro- the territory worked by the voya- historians and educators in Ti- pean exploration and settlement geurs, the backwoods fur traders conderoga prepared for yet an- of the North Country. whose pelts enriched New other visitors’ season at the site of Champlain’s journey down France. Ticonderoga was the America’s first Revolutionary the lake which came to bear his southernmost outpost of the War victory: Fort Ticonderoga. A little over an hour’s drive from Lake Placid, Ticonderoga is situated — town, village and fort — in the far southeastern corner of Essex County, just a short stone’s throw across Lake Cham- plain from the Green Mountains of Vermont. Fort Ticonderoga is an abso- lute North Country “must see” — but to appreciate this historical gem, one must know its history. Two centuries of battle It was the two-mile “carry” up the La Chute River from Lake Champlain through Ticonderoga village to Lake George that gave the site its name, a Mohican word that means “land between the wa- ters.” Overlooking the water highway connecting the two lakes as well as the St. Lawrence and Hudson rivers, Ticonderoga’s strategic importance made it the frontier for centuries between competing cultures: first between the northern Abenaki and south- ern Mohawk natives, then be- tween French and English colo- nizers, and finally between royal- ists and patriots in the American Revolution. -

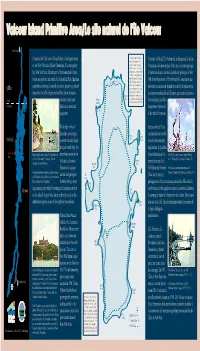

Valcour Primitive Area

Chambly Canal L’île Valcour comporte 12 km de Comprised of 1,100 acres, Valcour Island is the largest island sentiers de randonnée et 25 Couvrant 4,45 km2, l’île Valcour est la plus grande île du lac emplacements de camping on the New York side of Lake Champlain. It is managed by désignés. Des permis de camping Champlain, côté new-yorkais. Cette zone de nature protégée gratuits d’une durée maximale de the New York State Department of Environmental Conser- 14 jours sont émis par un gardien à l’intérieur du parc des Adirondacks est gérée par le New du parc. Par ailleurs, le site ayant vation as a primitive area within the Adirondack Park. Emphasis adopté le principe du premier York State Department of Environmental Conservation qui is placed on restoring its natural condition, preserving cultural arrivé, premier servi, aucune réser- préconise la restauration du milieu naturel et la préservation Quebec vation n’est acceptée. Pour de plus resources, and affording recreation that does not require amples renseignements sur l’île des ressources culturelles de l’île ainsi que les activités récréa- Beauty Valcour, veuillez communiquer Bay avec le Department of Environmen- Canada extensive man-made Valcour tives n’exigeant pas d’am- Landing tal Conservation au (518) 897-1200. United States facilities or motorized énagements importants equipment. ni de matériel motorisé. With eight miles of Avec sa côte de 13 km shoreline, consisting of constituée d’une variété Spoon Spoon New York a variety of rocky ledges Bay Island de corniches rocheuses and quiet sandy bays, the surplombant de paisibles You Are Here Boating along the rocky ledges of Valcour Island at the recreational potential on baies sablonneuses, le “Baby Blues,” similar to scenes found on Valcour Peru turn of the 19th century. -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas During the American Revolution Daniel S

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-11-2019 Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution Daniel S. Soucier University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, Military History Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Soucier, Daniel S., "Navigating Wilderness and Borderland: Environment and Culture in the Northeastern Americas during the American Revolution" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2992. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2992 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVIGATING WILDERNESS AND BORDERLAND: ENVIRONMENT AND CULTURE IN THE NORTHEASTERN AMERICAS DURING THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION By Daniel S. Soucier B.A. University of Maine, 2011 M.A. University of Maine, 2013 C.A.S. University of Maine, 2016 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School University of Maine May, 2019 Advisory Committee: Richard Judd, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-Adviser Liam Riordan, Professor of History, Co-Adviser Stephen Miller, Professor of History Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History Stephen Hornsby, Professor of Anthropology and Canadian Studies DISSERTATION ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Daniel S. -

Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812

American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. Plattsburgh, New York PREPARED FOR: The City of Plattsburgh, NY, 12901 IN ACCORDANCE WITH REQUIREMENTS OF GRANT FUNDING PROVIDED THROUGH: American Battlefield Protection Program Heritage Preservation Services National Park Service 1849 C Street NW (NC330) Washington, DC 20240 (Grant 2287-16-009) PREPARED BY: 4472 Basin Harbor Road, Vergennes, VT 05491 802.475.2022 • [email protected] • www.lcmm.org BY: Cherilyn A. Gilligan Christopher R. Sabick Patricia N. Reid 2019 1 American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Abstract As part of a regional collaboration between the City of Plattsburgh, New York, and the towns of Plattsburgh and Peru, New York, the Maritime Research Institute (MRI) at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) has been chosen to investigate six historical Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites: Valcour Island, Crab Island, Fort Brown, Fort Moreau, Fort Scott, and Plattsburgh Bay. These sites will require varying degrees of evaluation based upon the scope of the overall heritage tourism plan for the greater Plattsburgh area. The MRI’s role in this collaboration is to conduct a document review for each of the six historic sites as well as an archaeological assessment for Fort Brown and Valcour Island. The archaeological assessments will utilize KOCOA analysis outlined in the Battlefield Survey Manual of the American Battlefield Protection Program provided by the National Park Service. This deliverable fulfills Tasks 1 and 3 of the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) Grant 2887-16-009. -

GREEN I MOUNTAIN / GEOLO GIST

/ rfl1 GREEN / i MOUNTAIN GEOLO GIST QUARTERLY NEWSLEYFER OF THE VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY SPRING 1990 VOLUME 17 NUMBER I Vermont Geological Society 171h Annual PRESENTATION OF STUDENT PAPERS SATURDAY, APRIL 28, 1990, 8:30 AM UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT Room 004 KaIkin Building Directions: Kalkin Building lies immediately behind the Perkins Geology Building. Both are accessed from Coichester Ave. Room 004 is one of the basement roonis. The parking lot irnmc(liately in front of Perkins Hall will be available for VGS members attending the meeting. TABLE OF CONTENTS IRESIDENTSNOTE............................................................. 2 SPRING MEETING PROGRAM................................................ 3 SPRING MEETING ABSTRACTS ............................................. 4 CHARLES G. DOLL (1898-1990) ............................................. II THE Cl IARLES IX)LL CELEBRATION SERVICE .......................... 1 2 VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY BUSINESS AND NEWS ........... 13 NewMembers............................................................... 13 1)ues Report ................................................................. 1 3 Future Field Trips and Meetings......................................... 1 3 Editorial Notes ............................................................. 1 4 Eecuiivc (i'oiiimittec M inuics .......................................... 1 5 Esci-ulive (')iiuoiIiec Expciise Reiiiibursciiieiit (iudcliiics ........ 17 MELI'INGS & SEMINARS...................................................... 18 2 Green Mountain -

June 11, 2020 Location: Webinar

Lake Champlain Steering Committee Meeting Meeting Summary Thursday, June 11, 2020 Location: Webinar Attendance: Steering Committee members: Pete Laflamme (Co - Meeting Chair VTANR for Julie Moore), Julie Moore (Meeting Chair VTANR), Joe Zalewski (NYS DEC), Vic Putman (Chair, NY CAC), Mark Naud (VT CAC), Buzz Hoerr (Chair, E&O Committee), Jean-François Cloutier (Quebec MELCC, for Nathalie Provost), Neil Kamman (Chair, TAC), Pierre Leduc (Chair, Quebec CAC), Mario Paula (EPA R2 for Rick Balla), Steve Garceau (Quebec MNRF), Ryan Patch (VT AAFM for Alyson Eastman), Laura Trieschmann (ACCD), Mel Coté (EPA R1), Andrew Milliken (USFWS), Blake Glover (NRCS NY), Craig DiGiammarino (VTRANS), Vicky Drew (VT NRCS), Breck Bowden (Lake Champlain Sea Grant) Staff: LCBP: Colleen Hickey, Lauren Jenness, Jim Brangan, Ryan Mitchell, Matthew Vaughan, Mae Kate Campbell, Elizabeth Lee, Eric Howe, Meg Modley Gilbertson, Kathy Jarvis; Hannah Weiss, NEIWPCC: Susan Sullivan, Heather Radcliffe, NYS DEC: Koon Tang, Lauren Townley, Julie Berlinski; Sarah Coleman (VT ANR; LCBP VT Coordinator), EPA Region 1: MaryJo Feuerbach, Bryan Dore Guests: Tom Berry (Sen. Leahy’s office) Haley Pero (Sen. Sander’s office), Jonathan Carman (Cong. Stefanik’s Office), Thea Wurzburg (Cong. Welch’s Office), Justin Kenney 9:45 AM Connect to GoToMeeting webinar, networking 10:00 Meeting Begins Vermont ANR Chair · Welcome and Introductions. Pete LaFlamme welcomed the group, a round of introductions were made. · Draft Meeting Agenda review · ACTION ITEM: April 2020 Steering Committee meeting minutes approval ● ACTION ITEM: Approve Meeting Minutes from April 2020 Steering Committee Meeting Motion to approve by: Neil Kamman Second by: Andrew Milliken Discussion on the motion: None. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 1, Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1 The American Revolution and the Post-Revolutionary Era: A Historical Legacy Introduction From 1774 to 1783, the British government and its upstart American colony became locked in an increasingly bitter struggle as the Americans moved from violent protest over British colonial policies to independence As this scenario developed, intelligence and counterintelligence played important roles in Americas fight for freedom and British efforts to save its empire It is apparent that British General Thomas Gage, commander of the British forces in North America since 1763, had good intelligence on the growing rebel movement in the Massachusetts colony prior to the Battles of Lexington and Concord His highest paid spy, Dr Benjamin Church, sat in the inner circle of the small group of men plotting against the British Gage failed miserably, however, in the covert action and counterintelligence fields Gages successor, General Howe, shunned the use of intelligence assets, which impacted significantly on the British efforts General Clinton, who replaced Howe, built an admirable espionage network but by then it was too late to prevent the American colonies from achieving their independence On the other hand, George Washington was a first class intelligence officer who placed great reliance on intelligence and kept a very personal hand on his intelligence operations Washington also made excellent use of offensive counterintelligence operations but never created a unit or organization to conduct defensive counterintelligence or to coordinate its -

Book Reviews ……………………………………

IN THIS ISSUE ........................................................ Book Reviews …………………………………….. Charles Fish, In the Land of the Wild Onion: Travels along Vermont’s Winooski River. Helen Husher 176 Robert McCullough, Crossings: A History of Vermont Bridges. Leslie Goat 178 James L. Nelson, Benedict Arnold’s Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain but Won the American Revolution. Art Cohn 181 Peter Benes, Ed., Slavery/Antislavery in New England. Annual Proceedings of the Dublin Seminar for New England Folklife, Volume 28. Jane Williamson 183 Jeffrey Marshall, The Inquest. John A. Leppman 185 C. J. King, Four Marys and a Jessie: The Story of the Lincoln Women. Melanie Gustafson 187 Cynthia D. Bittinger, Grace Coolidge: Sudden Star (A Volume in the Presidential Wives Series). Deborah P. Clifford 189 Sarah Seidman and Patricia Wiley, Middlesex in the Making; History and Memories of a Small Vermont Town. Hans Raum 191 BOOK REVIEWS ........................................................ In the Land of the Wild Onion: Travels along Vermont’s Winooski River By Charles Fish (Burlington: University of Vermont Press and Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2006, pp. 253, $29.95). harles Fish’s book about the natural and cultural history of the Wi- C nooski River begins at the beginning—the headwaters in Cabot— and then winds like the river itself, flowing through personal conversa- tions, observations, and descriptions of small-boat handling (and mis- handling), to regional ecology, the inner workings of sewer plants, and the economic and social dynamics of mills. Fish introduces us to the to- pology of the Winooski Valley and to delicious terms like “fluvial geo- morphology” (p.