PROCEEDINGS of the 1993 NORTHEASTERN RECREATION RESEARCH SYMPOSIUM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S T a T E O F N E W Y O R K 3695--A 2009-2010

S T A T E O F N E W Y O R K ________________________________________________________________________ 3695--A 2009-2010 Regular Sessions I N A S S E M B L Y January 28, 2009 ___________ Introduced by M. of A. ENGLEBRIGHT -- Multi-Sponsored by -- M. of A. KOON, McENENY -- read once and referred to the Committee on Tourism, Arts and Sports Development -- recommitted to the Committee on Tour- ism, Arts and Sports Development in accordance with Assembly Rule 3, sec. 2 -- committee discharged, bill amended, ordered reprinted as amended and recommitted to said committee AN ACT to amend the parks, recreation and historic preservation law, in relation to the protection and management of the state park system THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, REPRESENTED IN SENATE AND ASSEM- BLY, DO ENACT AS FOLLOWS: 1 Section 1. Legislative findings and purpose. The legislature finds the 2 New York state parks, and natural and cultural lands under state manage- 3 ment which began with the Niagara Reservation in 1885 embrace unique, 4 superlative and significant resources. They constitute a major source of 5 pride, inspiration and enjoyment of the people of the state, and have 6 gained international recognition and acclaim. 7 Establishment of the State Council of Parks by the legislature in 1924 8 was an act that created the first unified state parks system in the 9 country. By this act and other means the legislature and the people of 10 the state have repeatedly expressed their desire that the natural and 11 cultural state park resources of the state be accorded the highest 12 degree of protection. -

Policy on the Possession of an Unloaded Firearm for the Purpose of Accessing Adjacent Lands for Lawful Hunting Purposes

Policy Title: Policy on the Possession of an Unloaded Firearm for the Purpose of Accessing Adjacent Lands for Lawful Hunting Purposes Directive: Section: OPR-POL-026 Operations Effective Date: 09/01/2016 Summary This Policy implements 9 NYCRR Section 375.1(p)(3), the regulation adopted by the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation (OPRHP) that authorizes the Commissioner to establish a list a facilities where a person may possess an unloaded firearm for the purpose of accessing adjacent properties for lawful hunting purposes. (See Notice of Adoption and Notice of Proposed Rulemaking published in the State Register on May 11, 2016 and January 27, 2016, respectively at http://docs.dos.ny.gov/info/register/2016/may11/pdf/rulemaking.pdf, at p.34 and http://docs.dos.ny.gov/info/register/2016/january27/pdf/rulemaking.pdf, at p.34). Policy Hunters may possess an unloaded firearm for the purpose of accessing adjacent lands for lawful hunting purposes at the following areas. Allegany Region Genesee Valley Greenway All sections of the Genesee Valley Greenway that are within Cattaraugus County. Boat Launches Chautauqua Lake (Chautauqua County) Long Point State Park, off Rte. 430 between Bemus Point and Maple Springs Allegheny Reservoir (Cattaraugus County) Allegany State Park (Quaker area) Friends Boat Launch. On Rte. 280, 2.5 miles south of Route 17 Lake Erie (Chautauqua County) Cattaraugus Creek (Sunset Bay), off Routes 5 and 20, approximately 2 miles west of Silver Creek Thruway interchange in the Hamlet of Sunset Bay Central Region Boat Launches Cazenovia Lake (Madison County) Helen L. McNItt State Park on East Lake Rd. -

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Valcour_Island Coordinates: 44°36′37.84″N 73°25′49.39″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Battle of Valcour Island Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Part of the American Revolutionary War Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley. The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Royal Savage is shown run aground and burning, Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after while British ships fire on her (watercolor by British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the unknown artist, ca. 1925) summer of 1776 fortifying those forts, and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet Date October 11, 1776 already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man Location near Valcour Bay, Lake Champlain, army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry Town of Peru / Town of Plattsburgh, it on the lake. -

030321 VLP Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga readies for new season LEE MANCHESTER, Lake Placid News TICONDEROGA — As countered a band of Mohawk Iro- name brought the eastern foothills American forces prepared this quois warriors, setting off the first of the Adirondack Mountains into week for a new war against Iraq, battle associated with the Euro- the territory worked by the voya- historians and educators in Ti- pean exploration and settlement geurs, the backwoods fur traders conderoga prepared for yet an- of the North Country. whose pelts enriched New other visitors’ season at the site of Champlain’s journey down France. Ticonderoga was the America’s first Revolutionary the lake which came to bear his southernmost outpost of the War victory: Fort Ticonderoga. A little over an hour’s drive from Lake Placid, Ticonderoga is situated — town, village and fort — in the far southeastern corner of Essex County, just a short stone’s throw across Lake Cham- plain from the Green Mountains of Vermont. Fort Ticonderoga is an abso- lute North Country “must see” — but to appreciate this historical gem, one must know its history. Two centuries of battle It was the two-mile “carry” up the La Chute River from Lake Champlain through Ticonderoga village to Lake George that gave the site its name, a Mohican word that means “land between the wa- ters.” Overlooking the water highway connecting the two lakes as well as the St. Lawrence and Hudson rivers, Ticonderoga’s strategic importance made it the frontier for centuries between competing cultures: first between the northern Abenaki and south- ern Mohawk natives, then be- tween French and English colo- nizers, and finally between royal- ists and patriots in the American Revolution. -

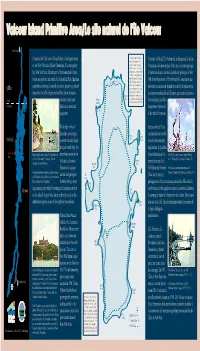

Valcour Primitive Area

Chambly Canal L’île Valcour comporte 12 km de Comprised of 1,100 acres, Valcour Island is the largest island sentiers de randonnée et 25 Couvrant 4,45 km2, l’île Valcour est la plus grande île du lac emplacements de camping on the New York side of Lake Champlain. It is managed by désignés. Des permis de camping Champlain, côté new-yorkais. Cette zone de nature protégée gratuits d’une durée maximale de the New York State Department of Environmental Conser- 14 jours sont émis par un gardien à l’intérieur du parc des Adirondacks est gérée par le New du parc. Par ailleurs, le site ayant vation as a primitive area within the Adirondack Park. Emphasis adopté le principe du premier York State Department of Environmental Conservation qui is placed on restoring its natural condition, preserving cultural arrivé, premier servi, aucune réser- préconise la restauration du milieu naturel et la préservation Quebec vation n’est acceptée. Pour de plus resources, and affording recreation that does not require amples renseignements sur l’île des ressources culturelles de l’île ainsi que les activités récréa- Beauty Valcour, veuillez communiquer Bay avec le Department of Environmen- Canada extensive man-made Valcour tives n’exigeant pas d’am- Landing tal Conservation au (518) 897-1200. United States facilities or motorized énagements importants equipment. ni de matériel motorisé. With eight miles of Avec sa côte de 13 km shoreline, consisting of constituée d’une variété Spoon Spoon New York a variety of rocky ledges Bay Island de corniches rocheuses and quiet sandy bays, the surplombant de paisibles You Are Here Boating along the rocky ledges of Valcour Island at the recreational potential on baies sablonneuses, le “Baby Blues,” similar to scenes found on Valcour Peru turn of the 19th century. -

22 AUG 2021 Index Acadia Rock 14967

19 SEP 2021 Index 543 Au Sable Point 14863 �� � � � � 324, 331 Belle Isle 14976 � � � � � � � � � 493 Au Sable Point 14962, 14963 �� � � � 468 Belle Isle, MI 14853, 14848 � � � � � 290 Index Au Sable River 14863 � � � � � � � 331 Belle River 14850� � � � � � � � � 301 Automated Mutual Assistance Vessel Res- Belle River 14852, 14853� � � � � � 308 cue System (AMVER)� � � � � 13 Bellevue Island 14882 �� � � � � � � 346 Automatic Identification System (AIS) Aids Bellow Island 14913 � � � � � � � 363 A to Navigation � � � � � � � � 12 Belmont Harbor 14926, 14928 � � � 407 Au Train Bay 14963 � � � � � � � � 469 Benson Landing 14784 � � � � � � 500 Acadia Rock 14967, 14968 � � � � � 491 Au Train Island 14963 � � � � � � � 469 Benton Harbor, MI 14930 � � � � � 381 Adams Point 14864, 14880 �� � � � � 336 Au Train Point 14969 � � � � � � � 469 Bete Grise Bay 14964 � � � � � � � 475 Agate Bay 14966 �� � � � � � � � � 488 Avon Point 14826� � � � � � � � � 259 Betsie Lake 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agate Harbor 14964� � � � � � � � 476 Betsie River 14907 � � � � � � � � 368 Agriculture, Department of� � � � 24, 536 B Biddle Point 14881 �� � � � � � � � 344 Ahnapee River 14910 � � � � � � � 423 Biddle Point 14911 �� � � � � � � � 444 Aids to navigation � � � � � � � � � 10 Big Bay 14932 �� � � � � � � � � � 379 Baby Point 14852� � � � � � � � � 306 Air Almanac � � � � � � � � � � � 533 Big Bay 14963, 14964 �� � � � � � � 471 Bad River 14863, 14867 � � � � � � 327 Alabaster, MI 14863 � � � � � � � � 330 Big Bay 14967 �� � � � � � � � � � 490 Baileys -

Appendices Section

APPENDIX 1. A Selection of Biodiversity Conservation Agencies & Programs A variety of state agencies and programs, in addition to the NY Natural Heritage Program, partner with OPRHP on biodiversity conservation and planning. This appendix also describes a variety of statewide and regional biodiversity conservation efforts that complement OPRHP’s work. NYS BIODIVERSITY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The New York State Biodiversity Research Institute is a state-chartered organization based in the New York State Museum who promotes the understanding and conservation of New York’s biological diversity. They administer a broad range of research, education, and information transfer programs, and oversee a competitive grants program for projects that further biodiversity stewardship and research. In 1996, the Biodiversity Research Institute approved funding for the Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation to undertake an ambitious inventory of its lands for rare species, rare natural communities, and the state’s best examples of common communities. The majority of inventory in state parks occurred over a five-year period, beginning in 1998 and concluding in the spring of 2003. Funding was also approved for a sixth year, which included all newly acquired state parks and several state parks that required additional attention beyond the initial inventory. Telephone: (518) 486-4845 Website: www.nysm.nysed.gov/bri/ NYS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION The Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) biodiversity conservation efforts are handled by a variety of offices with the department. Of particular note for this project are the NY Natural Heritage Program, Endangered Species Unit, and Nongame Unit (all of which are in the Division of Fish, Wildlife, & Marine Resources), and the Division of Lands & Forests. -

2017 NY State Camping Guide Part 1

Photo Credit: James Sickler NORTHEAST ADIRONDACK REGION ADIRONDACK NORTHEAST In the Adirondacks are found the 46 High Peaks that have the state’s highest vantage point (over 4,000 feet). Most of the major highways that serpentine through the Park’s magnificent landscape have been officially designated as Scenic Byways. Photo Credit: Heidi Oney 1.800.456.CAMP | 9 AUSABLE POINT 123 Sites | 518.561.7080 Ausable Point Campground protrudes from Route 9 into Lake Champlain and offers a shoreline comprised of natural sand and a gentle slope from many campsites. It borders a wildlife management area that offers a hiking trail, as well as water access for canoeists and sea kayakers to explore. With the city of Plattsburgh a short drive from this campground there is virtually no limit for entertainment opportunities. BUCK POND 116 Sites | 518.891.3449 Photo Credit: James Sickler Buck Pond Campground is located on 130-acre Buck Pond and offers secluded sites, numerous water access points, guarded bathing beach and an “easy-to-walk” trail which stretches for miles along an old, abandoned railroad bed. Camping equipment from tents to 30-foot RVs can be accommodated. The Campground offers a variety of recreational opportunities including: boating rentals, fishing, hiking and bicycling. 10 | newyorkstateparks.reserveamerica.com NORTHEAST ADIRONDACK REGION ADIRONDACK NORTHEAST MEADOWBROOK 62 Sites | 518.891.4351 Meadowbrook is the best bargain in town for those visiting the Lake Placid Olympic Training venues and the Village of Lake Placid. Located only four miles from the center of town, campers have no shortage of activities available to them. -

Sneak Peek Signs & Designs of a Young Woman EVL Chamber Spotlight: Life Long Study of Art and Light Inside This Issue

BEAT ON THE STREET:.......PAGE 11 April 1st - April 7th, 2021 Volume 16 ~ Issue 13 A FREE Weekly Publication Serving Ellicottville and Surrounding Communities Visit our website at: www.thevillagerny.com FREE CHQ-CATT CO’S COMMUNITY NEWspapER Area Events Illegal to Drink and Surf High Hopes for Summer 2021 NATIONAL NUTRITION MONTH March 1st - March 31st Lawmakers Prohibiting Use of Internet while Intoxicated Events Carefully Re-Open in Western New York Across the United States WOMEN’S HISTORY MONTH March 1st - March 31st Across the United States WINTER CARNIVAL March 13th & 14th Holiday Valley Resort, Ellicottville ALLEGANY STATE PARK Open Daily • 24 Hours Allegany State Park, Salamanca NANNEN ARBORETUM Open Daily • Till Dusk Town of Ellicottville, Ellicottville EVL VILLAGE PARK Open Daily • Till Dusk Sentencing includes fines and community service, a few even Village of Ellicottville, Ellicottville contain jail time. Ellicottville’s Chamber of Commerce is championing its members LETCHWORTH STATE PARK at every opportunity while making big summer plans. In the gears Open Daily • Till Dusk BY CHAD NEAL misuse and irresponsible use of is Red Head Days: Redheads, whether born or dyed, will have their Letchworth State Park, Castille the Internet. potential inaugural fun June 18-19 during Red Head Days. The Internet is a vastly used Some lawmakers including Joe LONG POINT STATE PARK resource in the United States. Kesonyu of Queens have brought BY JESSICA MIlleR learn while protecting one another Open Daily • Till Dusk More and more people are using up bills that include an “internet from potential exposure to a virus 4459 NY-430, Bemus Point the Internet for a plethora of jurisdiction” with a “policing The world is adapting and that still carries a lot of unknowns. -

Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812

American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Document Review and Archaeological Assessment of Selected Areas from the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. Plattsburgh, New York PREPARED FOR: The City of Plattsburgh, NY, 12901 IN ACCORDANCE WITH REQUIREMENTS OF GRANT FUNDING PROVIDED THROUGH: American Battlefield Protection Program Heritage Preservation Services National Park Service 1849 C Street NW (NC330) Washington, DC 20240 (Grant 2287-16-009) PREPARED BY: 4472 Basin Harbor Road, Vergennes, VT 05491 802.475.2022 • [email protected] • www.lcmm.org BY: Cherilyn A. Gilligan Christopher R. Sabick Patricia N. Reid 2019 1 American Battlefield Protection Program Grant 2287-16-009: Document Review and Archaeological Assessment Abstract As part of a regional collaboration between the City of Plattsburgh, New York, and the towns of Plattsburgh and Peru, New York, the Maritime Research Institute (MRI) at the Lake Champlain Maritime Museum (LCMM) has been chosen to investigate six historical Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites: Valcour Island, Crab Island, Fort Brown, Fort Moreau, Fort Scott, and Plattsburgh Bay. These sites will require varying degrees of evaluation based upon the scope of the overall heritage tourism plan for the greater Plattsburgh area. The MRI’s role in this collaboration is to conduct a document review for each of the six historic sites as well as an archaeological assessment for Fort Brown and Valcour Island. The archaeological assessments will utilize KOCOA analysis outlined in the Battlefield Survey Manual of the American Battlefield Protection Program provided by the National Park Service. This deliverable fulfills Tasks 1 and 3 of the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) Grant 2887-16-009. -

2019 ADK Budget Testimony 22 Jan 2019

22 January 2019 Testimony of the Adirondack Mountain Club (ADK) Joint Legislative Public Hearing, Environmental Conservation Portion 2019-2020 Executive Budget Proposal 23 January 2019 Good afternoon Chairwoman Krueger, Chairwoman Weinstein, Chairman Kaminsky, Chairman Englebright, and honored legislators. My name is Neil Woodworth. I am the Executive Director of the Adirondack Mountain Club (ADK). Thank you for the opportunity to testify today on the Governor’s Executive Budget proposal. Adirondack Mountain Club (ADK) ADK is dedicated to protecting and advocating for New York State’s wild lands and waters while also teaching people how to enjoy natural places responsibly. Since 1922, the organization has offered people opportunities to stay and play in as well as protect, discover, and explore the outdoors. Today, ADK has 30,000 members in 27 chapters statewide and is served by a professional, year-round staff. The organization is recognized as a vital voice in the commitment to environmental stewardship and ethical outdoor recreation in New York State. ADK members hike, camp, snowshoe, cross-country ski, paddle, and cycle the lands and waters of the Adirondack Park and other state lands. Our members are also monitors and maintainers of trails and recreation infrastructure as well as watchdogs of public lands and watersheds to monitor for invasive species or irresponsible and destructive motorized trespass. Environmental Protection Fund The Adirondack Mountain Club (ADK) supports Governor Andrew Cuomo’s proposed $300 million appropriation for the Environmental Protection Fund (EPF). This continues the original commitment of a 5-year $300 million EPF, and is great news as it will deliver $1.5 billion for conservation across the state over that time period. -

Addison Central-Western 723' 720' Adirondack Ski Center: See Alpine

69-70 70-1 71-2 72-3 Addison (Pinnacle Addison) - Addison Central-Western 723' 720' Adirondack Ski Center: See Alpine Meadows Northern 1000' 1000' 1000' 1000' Allegany State Park (Bova and Big Basin) - Red House Central-Western 190' 190' Alpine Lodge - Lake Placid Adirondacks Alpine Meadows (Adirondack Ski Center) - N. Greenfield Northern * * * * Anderlan - Little York Central-Western 350' 350' Andes Ski Center - Andes Catshills Armonk - Armonk Village SE: East of Hudson R Asech Hill - Gloversville Capital District Austerlitz Mt.: See Mountain Ten - Bald Hill - Farmingville Southern 180' 140' 140' 140' Bald Mtn.- Center Brunswick Capital District Baldpate - Crown Point Adirondacks Barton Mines - North Creek (Different from Harvey Mt.) Adirondacks Bassett Mt.: See Paleface - Bavarian Hausberg - Cairo Catskills and SE Beacon - Beacon (Small rope tow, near but separate from Dutchess) SE: East of Hudson R Bear Spring Mountain - Walton Catskills and SE Bearpen Mountain (Princeton Ski Bowl) - Prattsville Catskills and SE Beartown - Beekmantown Adirondacks Bellaire Dude Ranch (see Shayne's) Catskills Belleayre - Highmount Southern 1225' 1250' 1210' 1265' Berkshire Farm: See Darrow School - Berry School (Joe Berry School) - Binghampton Central-Western * * Bethpage - Farmingdale Southern 100' 100' 75' 100' Big Basin: See Allegany State Park - Big Bear: See Roxbury Ski Center Southern 1300' Big Birch: See Thunder Ridge Southern 675' 450' Big Rock Candy Mountain: See Rock Candy Mt. Northern 350' 300' 300' 300' Big Tupper - Tupper Lake Northern 800'