Other People's Money

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

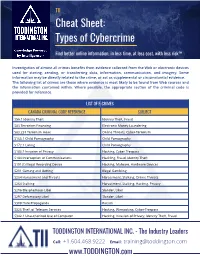

TII Cybercrime Cheat Sheet

TII Cheat Sheet: Types of Cybercrime Find better online information, in less time, at less cost, with less risk™ Investigation of almost all crimes benefits from evidence collected from the Web or electronic devices used for storing, sending, or transferring data, information, communication, and imagery. Some information may be directly related to the crime, or act as supplemental or circumstantial evidence. The following list of crimes are those where evidence is most likely to be found from Web sources and the information contained within. Where possible, the appropriate section of the criminal code is provided for reference. LIST OF E-CRIMES CANADA CRIMINAL CODE REFERENCE SUBJECT S56.1 Identity Theft Identity Theft, Fraud S83 Terrorism Financing Electronic Money Laundering S83.231 Terrorism Hoax Online Threats, Cyber-Terrorism S163.1 Child Pornography Child Pornography S172.1 Luring Child Pornography S183.1 Invasion of Privacy Hacking, Cyber-Trespass S184 Interception of Communications Hackling, Fraud, Identity Theft S191(1) Illegal Recording Device Hacking, Malware, Hardware Devices S201 Gaming and Betting Illegal Gambling S264 Harassment and Threats Harassment, Stalking, Online Threats S264 Stalking Harassment, Stalking, Hacking, Privacy S296 Blasphemous Libel Slander, Libel S297 Defamatory Libel Slander, Libel S308 Hate Propaganda Racism S326 Theft of Telecom Services Hacking, Wirejacking, Cyber-Trespass S342.1 Unauthorized Use of Computer Hacking, Invasion of Privacy, Identity Theft, Fraud TODDINGTON INTERNATIONAL INC. - The Industry -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Cybercrime Presentation

Cybercrime ‐ Marshall Area Chamber of October 10, 2017 Commerce CYBERCRIME Marshall Area Chamber of Commerce October 10, 2017 ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. About the Presenter Jeffrey Kline − 27 years of information technology and information security experience − Master of Science in Information Systems from Dakota State University − Technology and Management Consulting with RSM − Located in Sioux Falls, South Dakota • Rapid Assessment® • Data Storage SME • Virtual Desktop Infrastructure • Microsoft Windows Networking • Virtualization Platforms ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. RSM US LLP 1 Cybercrime ‐ Marshall Area Chamber of October 10, 2017 Commerce Content - Outline • History and introduction to cybercrimes • Common types and examples of cybercrime • Social Engineering • Anatomy of the attack • What can you do to protect yourself • Closing thoughts ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. INTRODUCTION TO CYBERCRIME ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. RSM US LLP 2 Cybercrime ‐ Marshall Area Chamber of October 10, 2017 Commerce Cybercrime Cybercrime is any type of criminal activity that involves the use of a computer or other cyber device. − Computers used as the tool − Computers used as the target ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. Long History of Cybercrime John Draper uses toy whistle from Cap’n Crunch cereal 1971 box to make free phone calls Teller at New York Dime Savings Bank uses computer to 1973 funnel $1.5 million into his personal bank account First convicted felon of a cybercrime – “Captain Zap” 1981 who broke into AT&T computers UCLA student used a PC to break into the Defense 1983 Department’s international communication system Counterfeit Access Device and Computer Fraud and 1984 Abuse Act was passed ©2017 RSM US LLP. -

Impostor Scams

University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform Volume 54 2021 Impostor Scams David Adam Friedman Willamette University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr Part of the Internet Law Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation David A. Friedman, Impostor Scams, 54 U. MICH. J. L. REFORM 611 (2021). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjlr/vol54/iss3/3 https://doi.org/10.36646/mjlr.54.3.imposter This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMPOSTOR SCAMS David Adam Friedman* ABSTRACT Impostor scams have recently become the most common type of consumer scam in America, surpassing identity theft. It has never been easier and more profitable to be an impostor scammer. Though the core of these scams dates back centuries, these fraudsters consistently find novel ways to manipulate human motives and emotions. Nonetheless, the public should not give up hope. Policymakers and private actors can slow down this scourge if they focus on the key chokepoints that impostor scammers rely upon to achieve their ends. This Article provides a roadmap for a solution to impostor scams, offering specific suggestions for mitigating this fraud today, while advocating the adoption of a “least-cost avoider” approach to address the whole of the ongoing problem. -

ATA July BI-2-REV2.Qxd 6/29/07 9:55 PM Page 30

ATA July BI-2-REV2.qxd 6/29/07 9:55 PM Page 30 Nigerian 419 E-Mail Scams By Keiran Dunne Continuing the series on cyber security that began in the April 2007 issue of The ATA Chronicle, this Taking full advantage of modern communications article will focus on e-mail messages that attempt to defraud innocent vic- technology, perpetrators indiscriminately send large tims using variants of the so-called “Nigerian 419 scam,” a form of fraud volumes of e-mail “invitations” to anonymous named after the section of the Nigerian penal code that it violates. potential “investors.” The 419 Scam: Advance Fee Fraud by Another Name Advance fee fraud is a variation of your account?’ The sums involved costs, or a requirement that the a centuries-old confidence trick are usually in the millions of dol- “investor” must have a certain amount whereby victims are persuaded to pro- lars, and the investor is promised a of money on deposit in an interna- vide money with the promise of real- large share, often 40%. The pro- tional bank in order to process the izing substantially larger returns.1 posed deal is often presented as a transaction, and so forth. Whatever Taking full advantage of modern com- ‘harmless’ white-collar crime, in the reason, once the money is munications technology, perpetrators order to dissuade participants from advanced to the 419 scammer(s), it is indiscriminately send large volumes later contacting the authorities. never seen again and the transaction is of e-mail “invitations” to anonymous Similarly, the money is often said to never concluded. -

Fraud Lexicons: Marketplace Deceptions in American Slang

Fraud Lexicons: Marketplace Deceptions in American Slang Edward J. Balleisen Author of Fraud: An American History from Barnum to Madoff All modern societies have illicit subcultures that emerge in domains outside the law, as well as grey areas that blur the boundaries between accepted and prohibited behavior. As with any subculture, these spheres tend to generate their own lingo, partly as a means of empowering insiders. Subcultures associated with the seamier side of selling, including outright business fraud and confidence swindles, have been no exception.1 Every American generation has produced its own patter about marketing deceptions, reflecting the application of enduring tactics and strategies to new technological, organizational, and cultural contexts. The resulting vernaculars peppered the talk of early nineteenth-century auctioneers, postbellum life insurance salesmen, and Gilded Age stock brokers; they similarly colored the speech of early twentieth-advertising men and stock promoters, post-World War II used car salesmen and hawkers of retail franchises, and early twenty-first century operators of internet investment message boards and online auction sites. 1David Maurer, “The Argot of Confidence Men,” American Speech 15 (April 1940): 113-23; David Maurer, The Big Con: The Story of the Confidence Man and the Confidence Game (Indianapolis, 1940). Since the early nineteenth century, fraud jargon has made its way into common speech, and so found its way into news coverage, public commentary, political oratory, and popular culture. Traces of these linguistic innovations reside in dictionaries and thesauruses of American slang. These compilations of fraud-related lingo furnish another perspective on the simultaneous mutability and consistency of deceptive business practices that I emphasize in Chapter Two of Fraud. -

Recovering the Stolen Sweets of Fraud and Corruption

OBEGEF – Observatório de Economia e Gestão de Fraude WORKING PAPERS Recovering the stolen #17 sweets of fraud and corruption >> Jeffrey Simser 2 >> FICHA TÉCNICA RECOVERING THE STOLEN SWEETS OF FRAUD AND CORRUPTION WORKING PAPERS Nº 17 / 2013 OBEGEF – Observatório de Economia e Gestão de Fraude Autores: Jeffrey Simser1 Editor: Edições Húmus 1ª Edição: Janeiro de 2013 ISBN: 978-989-8549-62-4 Localização web: http://www.gestaodefraude.eu Preço: gratuito na edição electrónica, acesso por download. Solicitação ao leitor: Transmita-nos a sua opinião sobre este trabalho. Paper in the International Conference Interdisciplinary Insights on Fraud and Corruption ©: É permitida a cópia de partes deste documento, sem qualquer modificação, para utilização individual. A reprodução de partes do seu conteúdo é permitida exclusivamente em documentos científicos, com indicação expressa da fonte. Não é permitida qualquer utilização comercial. Não é permitida a sua disponibilização através de rede electró- nica ou qualquer forma de partilha electrónica. Em caso de dúvida ou pedido de autorização, contactar directamente o OBEGEF ([email protected]). ©: Permission to copy parts of this document, without modification, for individual use. The reproduction of parts of the text only is permitted in scientific papers, with bibliographic information of the source. No commercial use is allowed. Not allowed put it in any network or in any form of electronic sharing. In case of doubt or request authorization, contact directly the OBEGEF ([email protected]). 1 BA, LL.B., LL.M; Toronto, Canada; [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are the personal views of the author and do not represent the views of the Government of Ontario. -

London Blue UK-Based Multinational Gang Runs BEC Scams Like a Modern Corporation

AGARI CYBER INTELLIGENCE DIVISION REPORT London Blue UK-Based Multinational Gang Runs BEC Scams like a Modern Corporation © Copyright 2018 AGARI Data, Inc. Executive Summary Agari has uncovered the working methods of a U.K./Nigerian gang with U.S.-based co-conspirators conducting Business Email Compromise (BEC) attacks against companies around the world. Nigeria has been a hub for scammers since During our research into London Blue, we long before the Internet came into wide use, identified a list of more than 50,000 corporate and it remains one of the world’s primary officials generated during a five-month period centers for active gangs, including many that in early 2018 and used to prepare for future are focused on BEC. BEC phishing campaigns. Among them, 71 percent were CFOs, 2 percent were executive But with London Blue, a Nigerian gang assistants, and the remainder were other has extended its base of operation into finance leaders. Western Europe, specifically into the United Kingdom, where at least two of the primary Targets included companies in a very broad London Blue members operate. We have also range of sectors, from small businesses to the identified 17 additional collaborators located largest multinational corporations. Several of in the United States and Western Europe who the world’s biggest banks each had dozens of are primarily involved in moving stolen funds. executives listed. The group also singled out mortgage companies for special attention, London Blue operates like a modern which would enable scams that steal real corporation. Its members carry out specialized estate purchases or lease payments. -

THE RISE of FINANCIAL FRAUD: SCAMS NEVER Changebut

THE RISE OF FINANCIAL FRAUD: SCAMS NEVER CHANGE but DISGUISES DO BY KIMBERLY BLANTON February 2012 INTRODUCTION The incidence of financial fraud in the United States is on the rise. Americans submitted more than 1.5 million complaints about financial and other fraud in 2011 – a 62 percent increase in just three years – according to the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) annual “Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book” the most comprehensive database of U.S. fraud trends (see Figure 1). Joe Borg, head of Alabama’s securities commission and a leader among state securities regula- tors, agreed there is a proliferation of fraud, and he largely blames the Internet. His agency had an unprecedented 31-case backlog of criminal trials involving financial fraud in September 2011. “It’s not unusual to have 20-25 convictions a year, but when we have 31 backed up – and we’re trying them as fast as we can – the trend is up,” he said. Borg ticks off the reasons: “Downturn in the economy. Fear among the public. The idea that the government can’t protect them anymore. Medical costs are going through the roof. Those are fears. The Internet is the vehicle. The Internet’s a big, big factor.” Neil Power, supervisor of the FBI’s Economic Crimes Squad in Boston, said the public is not fully aware of how pervasive fraud is, because only the most prominent cases, such as Bernard L. Madoff’s $50 billion Ponzi scheme, are covered by the Figure 1. Fraud Complaints Filed by Consumers, media. The vast majority of cases fly under the 2001-2010, in Millions public’s radar. -

Priority Development Assistance Fund Scam

Priority Development Assistance Fund scam From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Priority Development Assistance Fund scam, also called the PDAF scam or the pork barrel scam, is a political scandal involving the alleged misuse by several members of the Congress of the Philippines of their Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF, popularly called "pork barrel"), a lump-sum discretionary fund granted to each member of Congress for spending on priority development projects of the Philippine government, mostly on the local level. The scam was first exposed in the Philippine Daily Inquirer on July 12, 2013,[1] with the six-part exposé of the Inquireron the scam pointing to businesswoman Janet Lim-Napoles as the scam's mastermind after Benhur K. Luy, her second cousin and former personal assistant, was rescued by agents of theNational Bureau of Investigation on March 22, 2013, four months after he was detained by Napoles at her unit at the Pacific Plaza Towers in Fort Bonifacio.[2] Initially centering on Napoles' involvement in the 2004 Fertilizer Fund scam, the government investigation on Luy's testimony has since expanded to cover Napoles' involvement in a wider scam involving the misuse of PDAF funds from 2003 to 2013. It is estimated that the Philippine government was defrauded of some ₱10 billion in the course of the scam,[1] having been diverted to Napoles, participating members of Congress and other government officials. Aside from the PDAF and the fertilizer fund maintained by the Department of Agriculture, around ₱900 million -

Phishing for Victims

Theory and Crime: Does it Compute? Author Hutchings, Alice Published 2013 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Criminology and Criminal Justice DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2800 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365227 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Theory and Crime: Does it Compute? Alice Hutchings Bachelor of Arts in Criminology and Criminal Justice (Hons) School of Criminology and Criminal Justice Arts, Education and Law Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 Theory and Crime: Does it Compute? Abstract Abstract This research examines computer fraud and hacking offenders. The aim of this study is to provide a comprehensive understanding of computer crimes that compromise data and financial security, particularly hacking and computer frauds. This understanding will allow us to organise what we know about computer crime, so that it can be understood and explained. Computer crime was identified as an area that required further research, particularly in relation to offenders, which are a hard to access population. Particularly, it was noted that it is not understood why people became involved in computer crime offending. There has been a lack of theoretical examination in relation to these types of offenders. The theories that are applied in this research include differential association, social control theory, techniques of neutralisation, rational choice theory, labelling theory and structural strain theory, as well as feminist critiques of criminology. This was identified as an important area for research as there are many problems with the current crime prevention approaches and in investigating these offences. -

Bad Ideas All-In-One V2

Mutatis Mutandis: Things to Consider Nope, no fresh scams here, just a few things that have been on my mind for a while… I. Cons do not come with any blueprints, and any that claim to do so should not be followed but developed, built upon, overcome. Every scam textfile you read, every swindle idea you overhear, or every grift you pick up from the evening news, all are to be challenged, analyzed, and remixed to suit your needs. Scams are springboards of multifarious possibilities, they are not recipes that you memorize and then follow mindlessly. There is no such thing as ‘this is what works and this is how you do it.’ You memorize a short-changing bit, get your shit down pat, and then the cashier fucks your game up and hands you two fives instead of a ten. You must adapt general advice to your specific situation. You must give yourself enough room to change your game halfway. If you don’t, you will fail, get tripped up, get nailed. Any text which promises universal success “if you do everything this way” is lying. Following this, statements along the lines of “this won’t work” are to be ignored or laughed at, as are boasts akin to “this will definitely work.” Scams are inherently malleable to the given situation. People are stupid, the challenge lies in figuring out who’s got more brains, the grifter or the mark. There is ample room to situate yourself into your particular situation, to do your own research and make your own molding.