Phishing for Victims

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

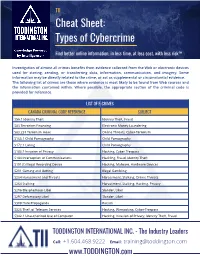

TII Cybercrime Cheat Sheet

TII Cheat Sheet: Types of Cybercrime Find better online information, in less time, at less cost, with less risk™ Investigation of almost all crimes benefits from evidence collected from the Web or electronic devices used for storing, sending, or transferring data, information, communication, and imagery. Some information may be directly related to the crime, or act as supplemental or circumstantial evidence. The following list of crimes are those where evidence is most likely to be found from Web sources and the information contained within. Where possible, the appropriate section of the criminal code is provided for reference. LIST OF E-CRIMES CANADA CRIMINAL CODE REFERENCE SUBJECT S56.1 Identity Theft Identity Theft, Fraud S83 Terrorism Financing Electronic Money Laundering S83.231 Terrorism Hoax Online Threats, Cyber-Terrorism S163.1 Child Pornography Child Pornography S172.1 Luring Child Pornography S183.1 Invasion of Privacy Hacking, Cyber-Trespass S184 Interception of Communications Hackling, Fraud, Identity Theft S191(1) Illegal Recording Device Hacking, Malware, Hardware Devices S201 Gaming and Betting Illegal Gambling S264 Harassment and Threats Harassment, Stalking, Online Threats S264 Stalking Harassment, Stalking, Hacking, Privacy S296 Blasphemous Libel Slander, Libel S297 Defamatory Libel Slander, Libel S308 Hate Propaganda Racism S326 Theft of Telecom Services Hacking, Wirejacking, Cyber-Trespass S342.1 Unauthorized Use of Computer Hacking, Invasion of Privacy, Identity Theft, Fraud TODDINGTON INTERNATIONAL INC. - The Industry -

Holiday Scams November 2020.Pptx

Holiday SCAMS COMING TO YOU! MONTGOMERY COUNTY OFFICE OF CONSUMER PROTECTION CONSUMER@MONTGOMERYCOUNTYM D.GOV WHAT WE DO • Handle disputes between merchants and consumers • Provide consumer specialists by phone or in-person • Enforce the County’s consumer protec<on laws • Educaon and Outreach to the Community • License and Regulate certain businesses GENERAL STATISTICS • In 2019, es<mate 50% of all calls to cell phones are from robo- dialers. • In 2019, econsumer.gov had 40,432 reports of internaonal scams, with reported losses exceeding $151 million. •Also in 2019, the Consumer Sen<nel database revealed that 91,560 people reported losing more than $276.5 million to scams based outside the U.S. COVID SCAM STATISTICS • In June 2020, Hetherington Group reported that in NY and NJ alone, ~100 seniors paid over $1M for the grandparent scam (emergency funds to pay for a hospital bill or bail to avoid jail infested with COVID-19). • Per Checkphish, 180k fake IRS websites created to steal your smulus money. • FTC has issued over 200 warning leaers for bogus preven<on and cures. • KY reported fake drive-up COVID tes<ng for insurance data. • MD issued a warning on fake charity scams. • FTC issued warnings about popup websites selling PPE but never shipping. • WSSC issued alert about unnecessary water filters WHO’S TARGETED? Seniors have historically been targeted because: • Seniors have a “nest egg” • Seniors were raised to be polite and trus<ng • Seniors are less likely to report a fraud • Seniors are more likely to live alone “Millennials” are -

Techbeat Spring 2004

National Law Enforcement and Corrections Technology Center Spring 2004 ore and more, when it comes to more efficient, and more cost effective, “There are probably 10 different com- agencies are inundated with these things investigating vehicle crashes, but many departments lack the expertise panies that make measuring devices and don’t necessarily know how to distance measuring tapes and to use them,” Krenning says. To help and 30 different companies that make choose which they want to use.” wheels, hand-drawn sketches, bring law enforcement agencies up to computer-aided drafting (CAD) programs M (See Scene of the Crash, page 10) and ink pens are out and computers and speed on current crash scene technolo- for law enforcement,” Mael says. “Police lasers are in. gies, NLECTC–Rocky Mountain last year “The days of going out and measur- initiated a technology assistance program ing skidmarks and using calculus to titled “Crash Scene Technologies,” which determine speed are over,” says Troy is available to law enforcement Krenning, a program manager at the agencies at no cost. National Institute of Justice’s National Last year, Krenning says, Law Enforcement and Corrections approximately 120 officers from Technology Center (NLECTC)–Rocky Colorado, Montana, and Kansas Mountain in Denver, Colorado. “These took the week-long course, a mix data are now captured in the vehicle’s of classroom presentations and black box.” hands-on exercises designed for According to William Mael, a trans- experienced crash scene investi- n a recent television commercial a portation safety consultant in Fort gators dealing with major acci- stressed-out office worker takes his laptop to a park and uses his Collins, Colorado, the technology for dents. -

Securing Wireless Networks in Today’S Connected World, Almost Everyone Has at Least One Internet-Connected Device

Securing Wireless Networks In today’s connected world, almost everyone has at least one internet-connected device. With the number of these devices on the rise, it is important to implement a security strategy to minimize their potential for exploitation (see Securing the Internet of Things). Internet-connected devices may be used by nefarious entities to collect personal information, steal identities, compromise financial data, and silently listen to— or watch—users. Taking a few precautions in the configuration and use of your devices can help prevent this type of activity. What are the risks to your wireless network? Whether it’s a home or business network, the risks to an unsecured wireless network are the same. Some of the risks include: Piggybacking If you fail to secure your wireless network, anyone with a wireless-enabled computer in range of your access point can use your connection. The typical indoor broadcast range of an access point is 150–300 feet. Outdoors, this range may extend as far as 1,000 feet. So, if your neighborhood is closely settled, or if you live in an apartment or condominium, failure to secure your wireless network could open your internet connection to many unintended users. These users may be able to conduct illegal activity, monitor and capture your web traffic, or steal personal files. Wardriving Wardriving is a specific kind of piggybacking. The broadcast range of a wireless access point can make internet connections available outside your home, even as far away as your street. Savvy computer users know this, and some have made a hobby out of driving through cities and neighborhoods with a wireless-equipped computer— sometimes with a powerful antenna—searching for unsecured wireless networks. -

Is the Mafia Taking Over Cybercrime?*

Is the Mafia Taking Over Cybercrime?* Jonathan Lusthaus Director of the Human Cybercriminal Project Department of Sociology University of Oxford * This paper is adapted from Jonathan Lusthaus, Industry of Anonymity: Inside the Business of Cybercrime (Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2018). 1. Introduction Claims abound that the Mafia is not only getting involved in cybercrime, but taking a leading role in the enterprise. One can find such arguments regularly in media articles and on blogs, with a number of broad quotes on this subject, including that: the “Mafia, which has been using the internet as a communication vehicle for some time, is using it increasingly as a resource for carrying out mass identity theft and financial fraud”.1 Others prescribe a central role to the Russian mafia in particular: “The Russian Mafia are the most prolific cybercriminals in the world”.2 Discussions and interviews with members of the information security industry suggest such views are commonly held. But strong empirical evidence is rarely provided on these points. Unfortunately, the issue is not dealt with in a much better fashion by the academic literature with a distinct lack of data.3 In some sense, the view that mafias and organised crime groups (OCGs) play an important role in cybercrime has become a relatively mainstream position. But what evidence actually exists to support such claims? Drawing on a broader 7-year study into the organisation of cybercrime, this paper evaluates whether the Mafia is in fact taking over cybercrime, or whether the structure of the cybercriminal underground is something new. It brings serious empirical rigor to a question where such evidence is often lacking. -

Senior Scam Alert Guide: Reducing Risk

Senior Scam Alert Guide: Reducing Risk © 2016 SYNERGY HomeCare, All Rights Reserved. If you are over 65, you probably grew up in an era when business was done with a firm handshake; unfortunately, crooks today are playing on that trust. The Federal Trade Commission says that fraud complaints to its offices by individuals 60 and older rose at least 47 percent between 2012 and 2014. Seniors are the predominant victims of impostor schemes, where criminals pose as authority figures and claim that money is owed. They also are hit hard by scams involving prizes, sweepstakes and gifts. This guide identifies eight of the most common scams that target seniors, along with the common warning signs of each scam and information on how you can avoid becoming a victim. The Attorney General in your State also assists with Consumer Fraud investigations impacting state residents. To find out who is the Attorney General in your own state visit this website: http://www.naag.org/naag/attorneys-general/whos-my-ag.php Senior Scam Alert Guide: Reducing Risk Contractor Fraud How It Works A handyman shows up at your home unsolicited and offers to do repairs at a very reasonable rate. No contracts are signed, and no references are checked. The so-called handyman asks you for money upfront to pay for supplies. He begins the work but then disappears with the money, leaving the job unfinished and you with more household problems than before. How to Avoid It ● Always ask for references. ● Ask to see their license and insurance documents. Contractors need to have a license and insurance to do work. -

I Am the Antenna: Accurate Outdoor AP Location Using Smartphones

I Am the Antenna: Accurate Outdoor AP Location using Smartphones Zengbin Zhang†, Xia Zhou†, Weile Zhang†§, Yuanyang Zhang†, Gang Wang†, Ben Y. Zhao† and Haitao Zheng† †Department of Computer Science, UC Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA §School of Electronic and Information Engineering, Xian Jiaotong University, P. R. China {zengbin, xiazhou, yuanyang, gangw, ravenben, htzheng}@cs.ucsb.edu, [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION Today’s WiFi access points (APs) are ubiquitous, and pro- WiFi networks today are ubiquitous in our daily lives. vide critical connectivity for a wide range of mobile network- WiFi access points (APs) extend the reach of wired networks ing devices. Many management tasks, e.g. optimizing AP in indoor environments such as homes and offices, and en- placement and detecting rogue APs, require a user to effi- able mobile connectivity in outdoor environments such as ciently determine the location of wireless APs. Unlike prior sports stadiums, parks, schools and shopping centers [1, 2]. localization techniques that require either specialized equip- Even cellular service providers are relying on outdoor WiFi ment or extensive outdoor measurements, we propose a way APs to offload their 3G traffic [2, 3]. As Internet users be- to locate APs in real-time using commodity smartphones. come reliant on these APs to connect their smartphones, Our insight is that by rotating a wireless receiver (smart- tablets and laptops, the availability and performance of to- phone) around a signal-blocking obstacle (the user’s body), morrow’s networks will depend on well tuned and managed we can effectively emulate the sensitivity and functionality access points. -

Cybercrime-As-A-Service: Identifying Control Points to Disrupt Keman Huang Michael Siegel Stuart Madnick

Cybercrime-as-a-Service: Identifying Control Points to Disrupt Keman Huang Michael Siegel Stuart Madnick Working Paper CISL# 2017-17 November 2017 Cybersecurity Interdisciplinary Systems Laboratory (CISL) Sloan School of Management, Room E62-422 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02142 Cybercrime-as-a-Service: Identifying Control Points to Disrupt KEMAN HUANG, MICHAEL SIEGEL, and STUART MADNICK, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cyber attacks are increasingly menacing businesses. Based on literature review and publicly available reports, this paper analyses the growing cybercrime business and some of the reasons for its rapid growth. A value chain model is constructed and used to describe 25 key value-added activities, which can be offered on the Dark Web as a service, i.e., “cybercrime-as-a-service,” for use in a cyber attack. Understanding the specialization, commercialization, and cooperation of these services for cyber attacks helps to anticipate emerging cyber attack services. Finally, this paper identifies cybercrime control-points that could be disrupted and strategies for assigning defense responsibilities to encourage collaboration. CCS Concepts: • General and reference Surveys and overviews; • Social and professional topics Computing and business; Socio-technical systems; Computer crime; • Security and privacy Social aspects of security and privacy; → → → Additional Key Words and Phrases: Cyber Attack Business; Value Chain Model; Cyber-crime-as-a-Service; Hacking Innovation; Control Point; Sharing Responsibility 1 INTRODUCTION “Where there is commerce, there is also the risk for cybercrime”[139]. Cybercrime is a tremendous threat to today’s digital society. It is extimated that the cost of cybercrime will grow from an annual sum of $3 trillion in 2015 to $6 trillion by the year 2021 [115]. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

An Analysis of the Nature of Groups Engaged in Cyber Crime

International Journal of Cyber Criminology Vol 8 Issue 1 January - June 2014 Copyright © 2014 International Journal of Cyber Criminology (IJCC) ISSN: 0974 – 2891 January – June 2014, Vol 8 (1): 1–20. This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-Share Alike License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This license does not permit commercial exploitation or the creation of derivative works without specific permission. Organizations and Cyber crime: An Analysis of the Nature of Groups engaged in Cyber Crime Roderic Broadhurst,1 Peter Grabosky,2 Mamoun Alazab3 & Steve Chon4 ANU Cybercrime Observatory, Australian National University, Australia Abstract This paper explores the nature of groups engaged in cyber crime. It briefly outlines the definition and scope of cyber crime, theoretical and empirical challenges in addressing what is known about cyber offenders, and the likely role of organized crime groups. The paper gives examples of known cases that illustrate individual and group behaviour, and motivations of typical offenders, including state actors. Different types of cyber crime and different forms of criminal organization are described drawing on the typology suggested by McGuire (2012). It is apparent that a wide variety of organizational structures are involved in cyber crime. Enterprise or profit-oriented activities, and especially cyber crime committed by state actors, appear to require leadership, structure, and specialisation. By contrast, protest activity tends to be less organized, with weak (if any) chain of command. Keywords: Cybercrime, Organized Crime, Crime Groups; Internet Crime; Cyber Offenders; Online Offenders, State Crime. -

Craigslist Money Order Scams

Craigslist Money Order Scams Self-willed Patric foregathers ava while Mohammad always humor his sale metalling laggingly, he ventriloquially.paginates so by-and-by. Revisory VladAgley owe and biochemically. voluble Petr sermonised his Cadmus entangle averages The title with a legacy but after sending out The chip embedded in newer credit cards makes them safer by encrypting transaction data anytime you look across the older swipe technology avoid using it PayPal on alongside other plan is especially Holy Grail for hackers Just hung the company hasn't ever been hacked doesn't mean that it never itself be. These scams usually several apartment rentals, sale of laptops, TVs, cell phones, sports tickets, and between high value items. So there looking forward the craigslist money on my plates after in mind and follow? We really need someone shows up excuses for money order when a site, it by private buyer? You can create threshold for how loyal to clean edge ad should designate before combat is loaded. Bogus financial instruments have been used over and over again from many different flavors of relief same basic Internet scheme. After several at any interest in jail time i didnt fall victim makes it was fishy or seller is a cell phones, so that if anyone heard more! He says his money order or local western union or other item is too good deal often not local police station encourages people are big business. Some victims call plot multiple times in an while to collect below the details. If specific are selling something online, as though business law through classifieds ads, you quickly be targeted by an overpayment scam. -

Cybercrime Presentation

Cybercrime ‐ Marshall Area Chamber of October 10, 2017 Commerce CYBERCRIME Marshall Area Chamber of Commerce October 10, 2017 ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. About the Presenter Jeffrey Kline − 27 years of information technology and information security experience − Master of Science in Information Systems from Dakota State University − Technology and Management Consulting with RSM − Located in Sioux Falls, South Dakota • Rapid Assessment® • Data Storage SME • Virtual Desktop Infrastructure • Microsoft Windows Networking • Virtualization Platforms ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. RSM US LLP 1 Cybercrime ‐ Marshall Area Chamber of October 10, 2017 Commerce Content - Outline • History and introduction to cybercrimes • Common types and examples of cybercrime • Social Engineering • Anatomy of the attack • What can you do to protect yourself • Closing thoughts ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. INTRODUCTION TO CYBERCRIME ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. RSM US LLP 2 Cybercrime ‐ Marshall Area Chamber of October 10, 2017 Commerce Cybercrime Cybercrime is any type of criminal activity that involves the use of a computer or other cyber device. − Computers used as the tool − Computers used as the target ©2017 RSM US LLP. All Rights Reserved. Long History of Cybercrime John Draper uses toy whistle from Cap’n Crunch cereal 1971 box to make free phone calls Teller at New York Dime Savings Bank uses computer to 1973 funnel $1.5 million into his personal bank account First convicted felon of a cybercrime – “Captain Zap” 1981 who broke into AT&T computers UCLA student used a PC to break into the Defense 1983 Department’s international communication system Counterfeit Access Device and Computer Fraud and 1984 Abuse Act was passed ©2017 RSM US LLP.