Silicon Den: Cybercrime Is Entrepreneurship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Criminal Law in the Face of Cyberattacks

APRIL 2021 REPORT CRIMINAL LAW IN THE FACE OF CYBERATTACKS Working group chaired by Bernard Spitz, President of the International and Europe Division of MEDEF, former President of the French Insurance Federation (FFA) General secretary: Valérie Lafarge-Sarkozy, Lawyer, Partner with the law firm Altana ON I SS I AD HOC COMM CRIMINAL LAW IN THE FACE OF CYBERATTACKS CRIMINAL LAW IN THE FACE OF CYBERATTACKS CLUB DES JURISTES REPORT Ad hoc commission APRIL 2021 4, rue de la Planche 75007 Paris Phone : 01 53 63 40 04 www.leclubdesjuristes.com FIND US ON 2 PREFACE n the shadow of the global health crisis that has held the world in its grip since 2020, episodes of cyberattacks have multiplied. We should be careful not to see this as mere coincidence, an unexpected combination of calamities that unleash themselves in Ia relentless series bearing no relation to one another. On the contrary, the major disruptions or transitions caused in our societies by the Covid-19 pandemic have been conducive to the growth of offences which, though to varying degrees rooted in digital, are also symptoms of contemporary vulnerabilities. The vulnerability of some will have been the psychological breeding ground for digital offences committed during the health crisis. In August 2020, the Secretary-General of Interpol warned of the increase in cyberattacks that had occurred a few months before, attacks “exploiting the fear and uncertainty caused by the unstable economic and social situation brought about by Covid-19”. People anxious about the disease, undermined by loneliness, made vulnerable by their distress – victims of a particular vulnerability, those recurrent figures in contemporary criminal law – are the chosen victims of those who excel at taking advantage of the credulity of others. -

Encrochatsure.Com

EncroChatSure.com . Better Sure than sorry! EncroChat® Reference & Features Guide EncroChatSure.com 1 EncroChatSure.com . Better Sure than sorry! EncroChatSure.com . Better Sure than sorry! EncroChat® - Feature List 2 EncroChatSure.com . Better Sure than sorry! EncroChatSure.com . Better Sure than sorry! EncroChat® - The Basics Question: What are the problems associated with disposable phones which look like a cheap and perfect solution because of a number of free Instant Messaging (IM) apps with built-in encryption? Answer: Let us point to the Shamir Law which states that the Crypto is not penetrated, but bypassed. At present, the applications available on play store and Apple App store for Instant Messaging (IM) crypto are decent if speaking cryptographically. The problem with these applications is that they run on a network platform which is quite vulnerable. The applications builders usually compromise on the security issues in order to make their application popular. All these applications are software solutions and the software’s usually work with other software’s. For instance, if one installs these applications then the installed software interfere with the hardware system, the network connected to and the operating system of the device. In order to protect the privacy of the individual, it is important to come up with a complete solution rather than a part solution. Generally, the IM applications security implementations are very devastating for the end user because the user usually ignores the surface attacks of the system and the security flaws. When the user looks in the account, they usually find that the product is nothing but a security flaw. -

Cybercrime Digest

Cybercrime Digest Bi-weekly update and global outlook by the Cybercrime Programme Office of the Council of Europe (C-PROC) 16 – 31 May 2021 Source: Council of E-evidence Protocol approved by Cybercrime Europe Convention Committee Date: 31 May 2021 “The 24th plenary of the Cybercrime Convention Committee (T-CY), representing the Parties to the Budapest Convention, on 28 May 2021 approved the draft “2nd Additional Protocol to the Convention on Cybercrime on Enhanced Co-operation and Disclosure of Electronic Evidence. […] Experts from the currently 66 States that are Parties to the Budapest Convention from Africa, the Americas, Asia-Pacific and Europe participated in its preparation. More than 95 drafting sessions were necessary to resolve complex issues related to territoriality and jurisdiction, and to reconcile the effectiveness of investigations with strong safeguards. […] Formal adoption is expected in November 2021 – on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Budapest Convention – and opening for signature in early 2022.” READ MORE Source: Council of GLACY+: Webinar Series to Promote Universality Europe and Implementation of the Budapest Convention on Date: 27 May 2021 Cybercrime “The Council of Europe Cybercrime Programme Office through the GLACY+ project and the Octopus Project, in cooperation with PGA's International Peace and Security Program (IPSP), are launching a series of thematic Webinars as part of the Global Parliamentary Cybersecurity Initiative (GPCI) to Promote Universality and Implementation of the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime and its Additional Protocol.” READ MORE Source: Europol Industrial-scale cocaine lab uncovered in Rotterdam Date: 28 May 2021 in latest Encrochat bust “The cooperation between the French National Gendarmerie (Gendarmerie Nationale) and the Dutch Police (Politie) in the framework of the investigation into Encrochat has led to the discovery of an industrial-scale cocaine laboratory in the city of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. -

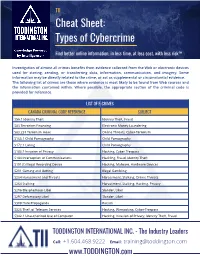

TII Cybercrime Cheat Sheet

TII Cheat Sheet: Types of Cybercrime Find better online information, in less time, at less cost, with less risk™ Investigation of almost all crimes benefits from evidence collected from the Web or electronic devices used for storing, sending, or transferring data, information, communication, and imagery. Some information may be directly related to the crime, or act as supplemental or circumstantial evidence. The following list of crimes are those where evidence is most likely to be found from Web sources and the information contained within. Where possible, the appropriate section of the criminal code is provided for reference. LIST OF E-CRIMES CANADA CRIMINAL CODE REFERENCE SUBJECT S56.1 Identity Theft Identity Theft, Fraud S83 Terrorism Financing Electronic Money Laundering S83.231 Terrorism Hoax Online Threats, Cyber-Terrorism S163.1 Child Pornography Child Pornography S172.1 Luring Child Pornography S183.1 Invasion of Privacy Hacking, Cyber-Trespass S184 Interception of Communications Hackling, Fraud, Identity Theft S191(1) Illegal Recording Device Hacking, Malware, Hardware Devices S201 Gaming and Betting Illegal Gambling S264 Harassment and Threats Harassment, Stalking, Online Threats S264 Stalking Harassment, Stalking, Hacking, Privacy S296 Blasphemous Libel Slander, Libel S297 Defamatory Libel Slander, Libel S308 Hate Propaganda Racism S326 Theft of Telecom Services Hacking, Wirejacking, Cyber-Trespass S342.1 Unauthorized Use of Computer Hacking, Invasion of Privacy, Identity Theft, Fraud TODDINGTON INTERNATIONAL INC. - The Industry -

2020 Identity Theft Statistics | Consumeraffairs

2020 Identity Theft Statistics | ConsumerAffairs Trending Home / Finance / Identity Theft Protection / Identity theft statistics Buyers Guides Last Updated 01/16/2020 News Write a review 2020Write a review Identity theft statistics Trends and statistics about identity theft Learn about identity theft protection by Rob Douglas Identity Theft Protection Contributing Editor In 2018, the Federal Trade Commission processed 1.4 million fraud reports totaling $1.48 billion in losses. According to the FTC’s “Consumer Sentinel Network Data Book,” the most common categories for fraud complaints were imposter scams, debt collection and identity theft. Credit card fraud was most prevalent in identity theft cases — more than 167,000 people reported a fraudulent credit card account was opened with their information. Identity theft trends in 2019 In the next year, the Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC) predicts identity theft protection services will primarily focus on data breaches, data abuse and data privacy. ITRC also predicts that https://www.consumeraffairs.com/finance/identity-theft-statistics.html 2020 Identity Theft Statistics | ConsumerAffairs consumers will become more knowledgeable about how data breaches work and expect companies to provide more information about the specific types of data breached and demand more transparency in general in data breach reports. Cyber attacks are more ambitious According to a 2019 Internet Security Threat Report by Symantec, cybercriminals are diversifying their targets and using stealthier methods to commit identity theft and fraud. Cybercrime groups like Mealybug, Gallmaker and Necurs are opting for off-the-shelf tools and operating system features such as PowerShell to attack targets. Supply chain attacks are up 78% Malicious PowerShell scripts have increased by 1,000% Microsoft Office files make up 48% of malicious email attachments Internet of Things threats on the rise Cybercriminals attack IoT devices an average of 5,233 times per month. -

Chapter 25: Taking Stock

Chapter 25 Taking Stock But: connecting the world meant that we also connected all the bad things and all the bad people, and now every social and political problem is expressed in software. We’ve had a horrible ‘oh shit’ moment of realisation, but we haven’t remotely worked out what to do about it. – Benedict Evans If you campaign for liberty you’re likely to find yourself drinking in bad company at the wrong end of the bar. –WhitDiffie 25.1 Introduction Our security group at Cambridge runs a blog, www.lightbluetouchpaper.org, where we discuss the latest hacks and cracks. Many of the attacks hinge on specific applications, as does much of the cool research. Not all applications are the same, though. If our blog software gets hacked it will just give a botnet one more server, but there are other apps from which money can be stolen, others that people rely on for privacy, others that mediate power, and others that can kill. I’ve already discussed many apps from banking through alarms to prepay- ment meters. In this chapter I’m going to briefly describe four classes of ap- plication at the bleeding edge of security research. They are where we find innovative attacks, novel protection problems, and thorny policy issues. They are: autonomous and remotely-piloted vehicles; machine learning, from adver- sarial learning to more general issues of AI in society; privacy technologies; and finally, electronic elections. What these have in common is that while previously, security engineering was about managing complexity in technology with all its exploitable side-e↵ects, we are now bumping up against complexity in human society. -

Cyber Romance Scam Victimization Analysis Using Routine Activity Theory Versus Apriori Algorithm

(IJACSA) International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol. 9, No. 12, 2018 Cyber Romance Scam Victimization Analysis using Routine Activity Theory Versus Apriori Algorithm Mohd Ezri Saad1 Siti Norul Huda Sheikh Abdullah2, Mohd Zamri Murah3 Commercial Crime Investigation Department Center for Cyber Security Faculty of Information Royal Malaysia Police, Bukit Aman Science and Technology Bangi, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Selangor, Malaysia Abstract—The advance new digital era nowadays has led to These cyber romance scams has fraud Australians out of the increasing cases of cyber romance scam in Malaysia. These millions every years [1], [5]. No exception to Malaysia that technologies have offered both opportunities and challenge, has been the top 6 countries that recorded highest number of depending on the purpose of the user. To face this challenge, the cybercrime cases, with total loses reaching RM1 billion key factors that influence the susceptibility to cyber romance (Source: Bernama Report in 2014). Other countries like scam need to be identified. Therefore, this study proposed cyber Taiwan, China, Thailand, Indonesia and Hong Kong also were romance scam models using statistical method and Apriori listed together. While, Sophos Threat Report in 2014 stated techniques to explore the key factors of cyber romance scam that cybercrime attacks have been increased in the first quarter victimization based on the real police report lodged by the of 2014 and 81% of them happened in Malaysia. This victims. The relationship between demographic variables such as phenomenon was in line with the rapid growth of Malaysia's age, education level, marital status, monthly income and independent variables such as level of computer skills and the digital economy [6]. -

Is the Mafia Taking Over Cybercrime?*

Is the Mafia Taking Over Cybercrime?* Jonathan Lusthaus Director of the Human Cybercriminal Project Department of Sociology University of Oxford * This paper is adapted from Jonathan Lusthaus, Industry of Anonymity: Inside the Business of Cybercrime (Cambridge, Mass. & London: Harvard University Press, 2018). 1. Introduction Claims abound that the Mafia is not only getting involved in cybercrime, but taking a leading role in the enterprise. One can find such arguments regularly in media articles and on blogs, with a number of broad quotes on this subject, including that: the “Mafia, which has been using the internet as a communication vehicle for some time, is using it increasingly as a resource for carrying out mass identity theft and financial fraud”.1 Others prescribe a central role to the Russian mafia in particular: “The Russian Mafia are the most prolific cybercriminals in the world”.2 Discussions and interviews with members of the information security industry suggest such views are commonly held. But strong empirical evidence is rarely provided on these points. Unfortunately, the issue is not dealt with in a much better fashion by the academic literature with a distinct lack of data.3 In some sense, the view that mafias and organised crime groups (OCGs) play an important role in cybercrime has become a relatively mainstream position. But what evidence actually exists to support such claims? Drawing on a broader 7-year study into the organisation of cybercrime, this paper evaluates whether the Mafia is in fact taking over cybercrime, or whether the structure of the cybercriminal underground is something new. It brings serious empirical rigor to a question where such evidence is often lacking. -

SERI Conference Proceedings SHORTLISTED PAPERS

National Centre of Excellence for Cybersecurity Technology PRESENTS AT Development & Entrepreneurship OUR PARTNERS Promoting Cybersecurity Education, Research and Innovation SERI Conference Proceedings SHORTLISTED PAPERS THEME AUTHORS INSTITUTE/ ORGANIZATION Data Privacy Signify North America Considerations during HARSHA BANAVARA Corporation, Burlington, Requirements Phase of MA USA IoT Product Development ASTRA: A Post AKSHAY JAIN Exploitation Red Teaming DR. BHUVNA J Jain University, Bengaluru tool SUBARNA PANDA zSpaze Technologies, New Space and New RAMESH KUMAR V Bengaluru Threats PRASANNA PHANINDRAN Easwari Engineering College, Chennai Cross-Channel Scripting Attacks (XCS) in Web SHASHIDHAR R Bennett University Applications Quantum Cryptography SANCHALI KSHIRSAGAR UMIT SNDT Women's and Use Cases: A Short DR. SANJYA PAWAR University, Mumbai Survey Paper SHRAVANI SHAHAPURE NCoE-DSCI, New Delhi Securing IoT using Tata Advanced System SHALINI DHULL Permissioned Blockchain Limited, Noida Parul University, Vadodara An Analysis of Internet of YASSIR FAROOQUI Sankalchand Patel University, Things(IoT) Architecture DR. KIRIT MODI Visnagar Zonal advisory at Consumer Cyber Security-Modern Era DR. SUMANTA BHATTACHARYA Challenge to Human Race Rights Organization BHAVNEET KAUR SACHDEV and it’s impact on COVID-19 Indian Institute of Human Data Privacy Considerations during Requirements Phase of IoT Product Development HARSHA BANAVARA Data Privacy Considerations during Requirements Phase of IoT Product Development Harsha Banavara Signify North America -

Cybercrime-As-A-Service: Identifying Control Points to Disrupt Keman Huang Michael Siegel Stuart Madnick

Cybercrime-as-a-Service: Identifying Control Points to Disrupt Keman Huang Michael Siegel Stuart Madnick Working Paper CISL# 2017-17 November 2017 Cybersecurity Interdisciplinary Systems Laboratory (CISL) Sloan School of Management, Room E62-422 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, MA 02142 Cybercrime-as-a-Service: Identifying Control Points to Disrupt KEMAN HUANG, MICHAEL SIEGEL, and STUART MADNICK, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cyber attacks are increasingly menacing businesses. Based on literature review and publicly available reports, this paper analyses the growing cybercrime business and some of the reasons for its rapid growth. A value chain model is constructed and used to describe 25 key value-added activities, which can be offered on the Dark Web as a service, i.e., “cybercrime-as-a-service,” for use in a cyber attack. Understanding the specialization, commercialization, and cooperation of these services for cyber attacks helps to anticipate emerging cyber attack services. Finally, this paper identifies cybercrime control-points that could be disrupted and strategies for assigning defense responsibilities to encourage collaboration. CCS Concepts: • General and reference Surveys and overviews; • Social and professional topics Computing and business; Socio-technical systems; Computer crime; • Security and privacy Social aspects of security and privacy; → → → Additional Key Words and Phrases: Cyber Attack Business; Value Chain Model; Cyber-crime-as-a-Service; Hacking Innovation; Control Point; Sharing Responsibility 1 INTRODUCTION “Where there is commerce, there is also the risk for cybercrime”[139]. Cybercrime is a tremendous threat to today’s digital society. It is extimated that the cost of cybercrime will grow from an annual sum of $3 trillion in 2015 to $6 trillion by the year 2021 [115]. -

Cybercrime Digest

Cybercrime Digest Bi-weekly update and global outlook by the Cybercrime Programme Office of the Council of Europe (C-PROC) 16-30 June 2020 Source: Council of C-PROC series of cybercrime webinars continue: Europe materials available, next topics and dates announced Date: 30 Jun 2020 Initiated in April, the C-PROC series of webinars on cybercrime have continued in the second half of June with more sessions, respectively dedicated to Cybercrime in Africa and the challenges of international cooperation, co-organized by the U.S. Departement of Justice (USDoJ) and the Council of Europe in the framework of the GLACY+ Project, Introduction to Cyberviolence, conducted in the framework of the CyberEast Project, Cybercrime and Criminal Justice in Cyberspace the regional seminar dedicated to Asisa- Pacific, under the GLACY+ Project, and International standards on collection and handling of electronic evidence, under the CyberSouth Project. New webinars are scheduled for the next period: Cybercrime and Criminal Justice in Cyberspace, the series of seminars hosted by the European Union and the Council of Europe (Africa, EN - 7 July 2020; Africa, FR - 9 July 2020; Latin America and Caribbean, EN - 20 July; Latin America and Caribbean, ES - 22 July]. For further updates, please check our webinars dedicated webpage. Source: Council of CyberSouth: Regional workshop on interagency Europe cooperation on the search, seizure and confiscation of Date: 1 Jul 2020 on-line crime proceeds “CyberSouth project organised a regional online workshop on interagency cooperation on the search, seizure and confiscation of on-line crime proceeds, on the 1st of July 2020. The event gathered around 30 participants from Law Enforcement agencies, Financial Investigation Units and prosecutors of priority countries as well as experts from United Kingdom, Romania and FBI. -

An Analysis of the Nature of Groups Engaged in Cyber Crime

International Journal of Cyber Criminology Vol 8 Issue 1 January - June 2014 Copyright © 2014 International Journal of Cyber Criminology (IJCC) ISSN: 0974 – 2891 January – June 2014, Vol 8 (1): 1–20. This is an Open Access paper distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial-Share Alike License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. This license does not permit commercial exploitation or the creation of derivative works without specific permission. Organizations and Cyber crime: An Analysis of the Nature of Groups engaged in Cyber Crime Roderic Broadhurst,1 Peter Grabosky,2 Mamoun Alazab3 & Steve Chon4 ANU Cybercrime Observatory, Australian National University, Australia Abstract This paper explores the nature of groups engaged in cyber crime. It briefly outlines the definition and scope of cyber crime, theoretical and empirical challenges in addressing what is known about cyber offenders, and the likely role of organized crime groups. The paper gives examples of known cases that illustrate individual and group behaviour, and motivations of typical offenders, including state actors. Different types of cyber crime and different forms of criminal organization are described drawing on the typology suggested by McGuire (2012). It is apparent that a wide variety of organizational structures are involved in cyber crime. Enterprise or profit-oriented activities, and especially cyber crime committed by state actors, appear to require leadership, structure, and specialisation. By contrast, protest activity tends to be less organized, with weak (if any) chain of command. Keywords: Cybercrime, Organized Crime, Crime Groups; Internet Crime; Cyber Offenders; Online Offenders, State Crime.