Airship Venture, Blackwood's Magazine May,1933

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Mahony 3S Working Paper 2018-31

! HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHIES OF THE FUTURE: IMAGINATION, EXPECTATION AND PREDICTION IN THE MAKING OF IMPERIAL ATMOSPHERE Martin Mahony 3S Working Paper 2018-31 1 ! Established in early 2011, and building on a tradition of leading environmental social science research at UEA, we are a group of faculty, researchers and postgraduate students taking forward critical social science approaches to researching the social and political dimensions of environment and sustainability issues. The overall aim of the group is to conduct world-leading research that better understands, and can potentially transform, relations between science, policy and society in responding to the unprecedented sustainability challenges facing our world. In doing this our approach is: INTERDISCIPLINARY, working at the interface between science and technology studies, human geography and political science, as well as linking with the natural sciences and humanities; ENGAGED, working collaboratively with publics, communities, civil society organisations, government and business; and REFLEXIVE, through being theoretically informed, self-aware and constructively critical. Our work is organised around fve interrelated research strands: KNOWLEDGES AND EXPERTISE PARTICIPATION AND ENGAGEMENT SCIENCE, POLICY AND GOVERNANCE TRANSITIONS TO SUSTAINABILITY SUSTAINABLE CONSUMPTION Science, Society and Sustainability (3S) Research Group 3S researchers working across these strands focus School of Environmental Sciences on a range of topics and substantive issues including: University of -

Airships Over Lincolnshire

Airships over Lincolnshire AIRSHIPS Over Lincolnshire explore • discover • experience explore Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum 2 Airships over Lincolnshire INTRODUCTION This file contains material and images which are intended to complement the displays and presentations in Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum’s exhibition areas. This file looks at the history of military and civilian balloons and airships, in Lincolnshire and elsewhere, and how those balloons developed from a smoke filled bag to the high-tech hybrid airship of today. This file could not have been created without the help and guidance of a number of organisations and subject matter experts. Three individuals undoubtedly deserve special mention: Mr Mike Credland and Mr Mike Hodgson who have both contributed information and images for you, the visitor to enjoy. Last, but certainly not least, is Mr Brian J. Turpin whose enduring support has added flesh to what were the bare bones of the story we are endeavouring to tell. These gentlemen and all those who have assisted with ‘Airships over Lincolnshire’ have the grateful thanks of the staff and volunteers of Cranwell Aviation Heritage Museum. Airships over Lincolnshire 3 CONTENTS Early History of Ballooning 4 Balloons – Early Military Usage 6 Airship Types 7 Cranwell’s Lighter than Air section 8 Cranwell’s Airships 11 Balloons and Airships at Cranwell 16 Airship Pioneer – CM Waterlow 27 Airship Crews 30 Attack from the Air 32 Zeppelin Raids on Lincolnshire 34 The Zeppelin Raid on Cleethorpes 35 Airships during the inter-war years -

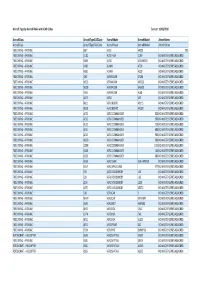

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016 AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AJ27 ACAC ARJ21 700 FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE CUB2 ACES HIGH CUBY NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE SACR ACRO ADVANCED NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A700 ADAM A700 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A500 ADAM A500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE F26T AERMACCHI SF260 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M326 AERMACCHI MB326 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M308 AERMACCHI MB308 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE LA60 AERMACCHI AL60 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AAT3 AERO AT3 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB11 AERO BOERO AB115 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB18 AERO BOERO AB180 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC52 AERO COMMANDER 520 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC50 AERO COMMANDER 500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC72 AERO COMMANDER 720 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC6L AERO COMMANDER 680 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC56 AERO COMMANDER 560 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M200 AERO COMMANDER 200 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE JCOM AERO COMMANDER 1121 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE VO10 AERO COMMANDER 100 NO MASTER -

Tk-480/481 Service Manual

800MHz/900MHz FM TRANSCEIVER TK-480/481 SERVICE MANUAL © 2011-5 PRINTED IN JA PAN SUPPLEMENT K3, K4, M4 versions B51-8977-00 (Y) PDF This service manual applies to products with A8A00001 (TK-480), B160001 (TK-481) or subsequent serial numbers. Refer to the TK-480/481 series service manual for any infor- mation which has not been covered in this manual. Knob (SEL) (K29-5232-03) Knob (VOL) (K29-5231-03) Whip antenna (T90-0636-25) : TK-480 (T90-0640-25) : TK-481 Panel assy Badge (A62-0981-04) (B43-1139-04) Knob (PTT) CONTENTS (K29-5157-03) GENERAL ....................................................2 DISASSEMBLY FOR REPAIR .....................3 PARTS LIST .................................................4 Packing PC BOARD (G53-0841-22) : K4 TX-RX UNIT (X57-5630-XX) ...................10 SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM ............................14 Cabinet assy (A02-3659-23) : K4 CAUTION Illustration is TK-480/481 K4 type. When using an external power connector, please use with maximum fi nal module protec- tion of 9V. This product complies with the RoHS directive for the European market. This product uses Lead Free solder. TK-480/481 Document Copyrights Firmware Copyrights Copyright 2011 by Kenwood Corporation. All rights re- The title to and ownership of copyrights for firmware served. embedded in Kenwood product memories are reserved for No part of this manual may be reproduced, translated, Kenwood Corporation. Any modifying, reverse engineering, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- copy, reproducing or disclosing on an Internet website of the tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, fi rmware is strictly prohibited without prior written consent of for any purpose without the prior written permission of Ken- Kenwood Corporation. -

Sustaining Design and Production Resources

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. The United Kingdom’s Nuclear Submarine Industrial Base Volume 1 Sustaining Design and Production Resources John F. Schank Jessie Riposo John Birkler James Chiesa Prepared for the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defence The research described in this report was prepared for the United King- dom’s Ministry of Defence. -

Ballooning Collection, the Cuthbert-Hodgson Collection, Which Is Probably One of the fi Nest of Its Kind in the World

SOCIETY NEWS qÜÉ=pçÅáÉíóÛë=iáÄê~êó b~êäó=_~ääççåáåÖ iáíÜçÖê~éÜë=~åÇ=mêáåíë ÜÉ=oçó~ä=^Éêçå~ìíáÅ~ä=pçÅáÉíó áãéçêí~åí=îáëì~ä=êÉÅçêÇ=çÑ=ã~åÛë qiáÄê~êó= ÜçìëÉë= çåÉ= çÑ= íÜÉ É~êäó= ~ëÅÉåíë= áåíç= íÜÉ= ~áê= ~í= íÜÉ ïçêäÇÛë=ÑáåÉëí=ÅçääÉÅíáçåë=çÑ=É~êäó îÉêó= Ç~ïå= çÑ= ~îá~íáçå= ~ë Ä~ääççåáåÖ= ã~íÉêá~ä= EÄççâëI éçêíê~óÉÇ= Äó= áääìëíê~íçêë= ~åÇ é~ãéÜäÉíëI= åÉïëé~éÉê= ÅìííáåÖëI ÉåÖê~îÉêë=çÑ=íÜÉ=íáãÉK éêáåíë= ~åÇ= äáíÜçÖê~éÜë= ~åÇ qÜÉ= Ä~ääççå= ï~ë= Äçêå= áå ÅçããÉãçê~íáîÉ= ãÉÇ~äëF= ïÜáÅÜ cê~åÅÉ= áå= NTUP= ÇìêáåÖ= íÜÉ= ä~íÉJ Ü~ë= ÄÉÉå= ìëÉÇ= Äó= êÉëÉ~êÅÜÉêë NUíÜ= ÅÉåíìêó= båäáÖÜíÉåãÉåí Ñêçã= dÉêã~åóI= cê~åÅÉ= ~åÇ= íÜÉ éìêëìáí= çÑ= ëÅáÉåíáÑáÅ= âåçïäÉÇÖÉX råáíÉÇ=pí~íÉëK íÜÉ=~Äáäáíó=íç=íê~îÉä=íÜêçìÖÜ=íÜÉ `çãéäÉãÉåíáåÖ= íÜÉ= ÑáåÉ ~áê=çéÉåÉÇ=ìé=éÉçéäÉëÛ=ãáåÇë=íç ÅçääÉÅíáçå= çÑ= É~êäó= Ä~ääççåáåÖ íÜÉ= éçëëáÄáäáíáÉë= çÑ= ~Éêá~ä ~åÇ= ~Éêçå~ìíáÅ~ä= Äççâë= áë= ~ å~îáÖ~íáçå=~åÇ=åÉïë=çÑ=íÜÉ=É~êäó ã~àçê= ÅçääÉÅíáçå= çÑ= ~êçìåÇ= TMM ~ëÅÉåíë= ï~ë= íê~åëãáííÉÇ= ê~éáÇäó É~êäó= Ä~ääççåáåÖ= äáíÜçÖê~éÜëL ~Åêçëë= bìêçéÉK= ^= é~êí= çÑ= íÜáë éêáåíëLéçëíÉêëK= qÜáë= ÅçääÉÅíáçå= Ô éêçÅÉëë= ï~ë= íÜÉ= éêçÇìÅíáçå= çÑ ïÜáÅÜ= áë= Ä~ëÉÇ= ã~áåäó= çå= íÜÉ åìãÉêçìë= äáíÜçÖê~éÜëLéêáåíë ÜçäÇáåÖë= çÑ= íÜÉ= `ìíÜÄÉêíJ ÅçããÉãçê~íáåÖ= é~êíáÅìä~ê eçÇÖëçå= `çääÉÅíáçå= EïÜáÅÜ= ï~ë ~ëÅÉåíë= çê= ~Éêá~ä= îçó~ÖÉëI= ~åÇ áå=NVQT=éìêÅÜ~ëÉÇ=áå=áíë=ÉåíáêÉíó íÜÉ= iáÄê~êó= ÜçäÇë= Éñ~ãéäÉë= çÑ Äó= páê= cêÉÇÉêáÅâ= e~åÇäÉó= m~ÖÉ ã~åó= îáÉïë= çÑ= ~ëÅÉåíë= ~Åêçëë o^Ép=iáÄê~êó=éÜçíçëK ~åÇ= éêÉëÉåíÉÇ= íç= íÜÉ= pçÅáÉíóI _êáí~áåI= cê~åÅÉ= ~åÇ= çíÜÉê dÉçêÖÉ=`êìáÅâëÜ~åâ=Úq~ñá=_~ääççåëÛ=Ô Ú^=ëÅÉåÉ=áå=íÜÉ=c~êÅÉ=çÑ=içÑíó -

Contract Number

Contract Number Contract Title Contract Current Contract Current Total Vendor Name Start Date End Date Contract Value 22A/2132/0210 PROVISION OF ESTABLISHMENT SUPPORT AND TRAINING SERVICES TO (FORMER) NRTA ESTABLISHMENTS 16 Mar 2007 30 Jun 2011 439,664,890.47 VT FLAGSHIP LTD AARC1A/00024 CONTRACTOR LOGISTIC SUPPORT SERVICE FOR ALL MARKS FOR ALL MARKS OF THE VC10 AIRCRAFT PROJECT 18 Dec 2003 31 Mar 2011 463,471,133.00 BAE SYSTEMS (OPERATIONS) LIMITED AARC1B/00188 TRISTAR INTEGRATED OPERATIONAL SUPPORT 20 Oct 2008 31 Dec 2015 118,177,227.00 MARSHALL OF CAMBRIDGE AEROSPACE LIMITED ACT/01397 PROVISION OF AIRCRAFT, INSTRUCTORS & SERVICES TO SUPPORT UAS & EFT, YRS 5 & 6 7 Jan 2009 31 Mar 2019 163,910,977.00 BABCOCK AEROSPACE LIMITED ACT/03528 CATERING (INCLUDING FOOD SUPPLY) RETAIL AND LEISURE SERVICES AND MESS AND HOTEL SERVICES TO VARIOUS RAF 5 Jan 2011 31 May 2018 145,198,692.00 ISS MEDICLEAN LIMITED STATIONS ACROSS THE UNITED KINGDOM AFSUP/0004 SHIP CLUSTER OWNER CONTRACT 23 Jun 2008 23 Jun 2013 180,962,000.00 CAMMELL LAIRD SHIPREPAIRERS & SHIPBUILDERS LIMITED AHCOMM1/00035 APACHE MTADS 11 May 2005 6 Mar 2011 188,407,408.00 WESTLAND HELICOPTERS LIMITED AHCOMM2/2030 APACHE INTEGRATED OPERATIONAL SUPPORT 29 Sep 2009 31 Dec 2030 957,949,173.09 WESTLAND HELICOPTERS LIMITED AHCOMM2/2042 APACHE SUSTAINMENT SPARES 27 Apr 2005 1 May 2009 165,516,251.00 WESTLAND HELICOPTERS LIMITED AHCOMM2/2064 INTERIM SUPPORT ARRANGEMENT 1 Apr 2007 30 Nov 2014 130,884,574.89 WESTLAND HELICOPTERS LIMITED AHCOMM2/2064/1 INTERIM SUPPORT ARRANGEMENT 1 Apr 2007 31 Mar -

The Airship, History and Handling, 18 Oct 2002 Messrs Brian Hussey and Don Williams Spoke to Us on Airships

The Airship, History and Handling, 18 Oct 2002 Messrs Brian Hussey and Don Williams spoke to us on Airships. They introduced us to the Airship Heritage Trust (based at Cardington) and the Airship Association. We were each given a copy of Engineering Technology, May 2001 in which Don Williams had an article on Airship Control by Remote Sensing. A Brief History - Brian Hussey The history of airships gives a good understanding of what they are, and of their associated problems. The first thoughts were in 1670 in Italy, when a gondola supported by four evacuated copper spheres about a metre in diameter was proposed – it would not have worked. The first people to fly were the Montgolfiers in their hot air balloon in 1783, heated by a bonfire on the ground - though they believed it was smoke that gave buoyancy, and used rather noisome fuel to produce it - its range was limited. Only eighteen months later the Channel was crossed, from Dover to Calais – troubles with lift meant that the crew had to throw out every portable thing, including their outer clothing. The first successful airship flew in 1898, designed by Santos Dumont who had designed a 3½ HP petrol engine for the purpose. He used one for personal transport round Paris… Airships typically fly at between 1000 and 2000 ft, lift being reduced at higher altitudes. Lift is provided by a lighter-than-air gas: hydrogen being lightest but flammable – particularly if contaminated by air leakage; the non-inflammable helium, though more expensive (10% of the cost of a new airship), is preferable and can be recycled. -

Brooklands Aerodrome & Motor

BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY (June 2017) Radley House Partnership BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS CONTENTS Aerodrome Road 2 The 1907 BARC Clubhouse 8 Bellman Hangar 22 The Brooklands Memorial (1957) 33 Brooklands Motoring History 36 Byfleet Banking 41 The Campbell Road Circuit (1937) 46 Extreme Weather 50 The Finishing Straight 54 Fuel Facilities 65 Members’ Hill, Test Hill & Restaurant Buildings 69 Members’ Hill Grandstands 77 The Railway Straight Hangar 79 The Stratosphere Chamber & Supersonic Wind Tunnel 82 Vickers Aviation Ltd 86 Cover Photographs: Aerial photographs over Brooklands (16 July 2014) © reproduced courtesy of Ian Haskell Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY Radley House Partnership Timelines: June 2017 Page 1 of 93 ‘AERODROME ROAD’ AT BROOKLANDS, SURREY 1904: Britain’s first tarmacadam road constructed (location?) – recorded by TRL Ltd’s Library (ref. Francis, 2001/2). June 1907: Brooklands Motor Circuit completed for Hugh & Ethel Locke King and first opened; construction work included diverting the River Wey in two places. Although the secondary use of the site as an aerodrome was not yet anticipated, the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club soon encouraged flying there by offering a £2,500 prize for the first powered flight around the Circuit by the end of 1907! February 1908: Colonel Lindsay Lloyd (Brooklands’ new Clerk of the Course) elected a member of the Aero Club of Great Britain. 29/06/1908: First known air photos of Brooklands taken from a hot air balloon – no sign of any existing route along the future Aerodrome Road (A/R) and the River Wey still meandered across the road’s future path although a footbridge(?) carried a rough track to Hollicks Farm (ref. -

The Monthly Journal of the North Shore Vintage Car Club December/January 2020/21

North Shore Vintage Car Club Your journal Your stories Your photos Your cars Progress: Your ideas Your committee The monthly journal of the North Shore Vintage Car Club December/January 2020/21 1 Progress Editorial December 2020 Firstly let me apologise for the late arrival of this edition. The morning after the last committee meeting Helen and I flew down to Queenstown to start a 12 day road trip across the Deep South. We travelled around Queenstown, Arrowtown, Gore, Invercargill, Riverton, The Caitlins, then up to Dunedin. We visited lots of museums, saw sea-lions and the World’s Fastest Indian. After driving the Otago and Southland roads it’s now obvious to me why Veteran and Vintage vehicles are so popular down there. Miles of gently curving roads with hardly another car to be seen. I didn’t think of the Harbour Bridge once! So that’s the end of another year at the NSVCC and eleven more issues of Progress “out of the door”. At this stage it would be remiss of me not to thank all of those who have contributed to this publication. Particular thanks must go to Terry Costello, Bruce Skinner and Richard Bampton who without fail have contributed something to every edition. Apologies to Richard for refusing to publish his scurrilous article and photograph implying that all Fords would be better badged Holdens. 2020 has been a strange year but how lucky we are to be down here in the South Pacific well away from the ravages of Covid, free from the stresses of Brexit and the insanity of the US presidential elections. -

Binocular-Revolver 8 & 12,5 X 50; 1927-1930

Binocular - revolver 8 & 12, 5 x 50; 1927-1930 I. Introduction The binocular was built app.; in 1927-1930 by Company V-A. Ltd. It is a revolver model with two oculars and different magnifications of the oculars. The quality of the material, which was used for make this binocular, indicated that it was manufactured before 1930. It was preceding the big economic crises which soon occurred in the world. Pict 1&2; revolver 8 &12, 5 revolver; London V-A. Ltd; ©Anna Vacani II. V-A. Ltd London Pict 3; 8 &12, 5 revolver; London V-A. Ltd, production logo; ©Anna Vacani 1 We would like to introduce the Company V-A. Ltd. It is well known British Company, but not for a production of binoculars. 1. The short history of the V-A. Ltd Two letters of the name of company means – Vickers-Armstrong Limited. Up to 1927 in Britain were two separate companies – Vickers Limited and Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Company. In 1927 the companies decided to join of the assets into one - Vickers- Armstrong Limited, private company. In 1968 the company was partly nationalised, in 1970s process of nationalization took over another part of the company. Since they united, the company was buying many other big companies, as: - Ruwolt Ltd – it produced armaments for the Australian Government. 2. Production of the V-A. ltd Since 1927 the company was produced large items, among them; - Armaments, as machine gun for aircraft or tanks; - Shipbuilding – the company was the most significant warship producer in the world. The company owned the Naval Construction Yard, in Cumbria; and the Naval Yard at High Walker, on the river Tyne. -

The Airship's Potential for Intertheater and Intratheater Airlift

ii DISCLAIMER This thesis was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States Air Force. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page Logistics Flow During The Gulf War 1 Introduction 1 Strategic lift Phasing 4 Transportation/Support Modes 8 Mobility Studies 16 Summary 19 Conclusion 23 Notes 24 Filling The Gap: The Airship 28 Prologue 28 Introduction 31 The Airship in History 32 Airship Technology 42 Potential Military Roles 53 Conclusion 68 Epilogue 69 Notes 72 Selected Bibliography 77 iv ABSTRACT This paper asserts there exists a dangerous GAP in US strategic intertheater transportation capabilities, propounds a model describing the GAP, and proposes a solution to the problem. Logistics requirements fall into three broad, overlapping categories: Immediate, Mid- Term, and Sustainment requirements. These categories commence and terminate at different times depending on the theater of operations, with Immediate being the most time sensitive and Sustainment the least. They are: 1. Immediate: War materiel needed as soon as combat forces are inserted into a theater of operations in order to enable them to attain a credible defensive posture. 2. Mid-Term: War materiel, which strengthens in-place forces and permits expansion to higher force levels. 3. Sustainment: War materiel needed to maintain combat operations at the desired tempo. US strategic transport systems divide into two categories: airlift and sealift.