Airships Over Lincolnshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As the Upkeep Bomb Was Not Only a Different Shape to Contemporary

CARRYING UPKEEP As the Upkeep bomb was not only a different shape to contemporary bombs but also had to be spun before release, Barnes Wallis and Vickers-Armstrongs had to come up with a purpose built mounting to be fitted to the Type 464 Lancasters. This section was the most significant and important of all the Type 464 modifications, yet due to its position, in shadow under the black painted belly of the Lancaster, it has never clearly been illustrated before. 14 15 starboard front port rear the calliper arms The four calliper arms were made of cast aluminium with the connecting piece at the apex made of machined steel. Each apex piece contained a circular hub upon which the Upkeep would be suspended. The four arms were attached to the fuselage by heavy duty brackets which allowed the arms to rotate freely outwards to allow a clean release of the bomb. To load the Upkeep, the arms were closed onto it and retained in that position by means of a heavy-duty cable in an inverted ‘Y’ shaped form, with each of the V shaped lengths being connected to one of the front calliper arms, while the stem was attached to a standard 4000lb ‘Type F’ bomb release unit. After the arms were closed, the threaded ends of the cables were fitted through eyelets in the front calliper arms, and retained in position by large bolts, which also allowed for some adjustment and tensioning. 16 17 port front starboard spinning the Upkeep To enable the Upkeep to be spun, A Vickers Variable Speed Gear (VSG) unit was installed forward of the calliper arms and securely bolted to the roof of the bomb bay. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

3.1 the Dambusters Revisited

The Dambusters Revisited J.L. HINKS, Halcrow Group Ltd. C. HEITEFUSS, Ruhr River Association M. CHRIMES, Institution of Civil Engineers SYNOPSIS. The British raid on the Möhne, Eder and Sorpe dams on the night of 16/17 May, 1943 caused the breaching of the 40m high Möhne and 48m high Eder dams and serious damage to the 69m high Sorpe dam. This paper considers the planning for the raid, model testing, the raid itself, the effects of the breaches and the subsequent rehabilitation of the dams. Whilst the subject is of considerable historical interest it also has significant contemporary relevance. Events following the breaching of the dams have been used for the calibration of dambreak studies and emphasise the vulnerability of road and railway bridges which is not always acknowledged in contemporary studies. INTRODUCTION In researching this paper the authors have been very struck by the human interest in the story of English, German and Ukrainian people, whether civilian or in uniform, who participated in some aspect of the raid or who lost their lives or homes. As befits a paper for the British Dam Society, this paper, however, concentrates on the technical questions that arise, leaving the human story to others. This paper was prompted by the BDS sponsored visit, in April 2009, to the Derwent Reservoir by 43 members of the Association of Friends of the Hubert-Engels Institute of Hydraulic Engineering and Applied Hydromechanics at Dresden University of Technology. There is a small museum at the dam run by Vic Hallam, an employee of Severn Trent Water. -

Prusaprinters

LZ-129 Hindenburg - scale 1/1000 vandragon_de VIEW IN BROWSER updated 14. 2. 2019 | published 14. 2. 2019 Summary famous Air Ship In my model series in 1:1000, the largest airship should not be missing. History: LZ 129 Hindenburg was a large German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg class, the longest class of flying machine and the largest airship by envelope volume. It was designed and built by the Zeppelin Company (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH) on the shores of Lake Constance in Friedrichshafen and was operated by the German Zeppelin Airline Company .The airship flew from March, 1936 until it was destroyed by fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937 while attempting to land at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Manchester Township, New Jersey at the end of the first North American transatlantic journey of its second season of service with the loss of 36 lives. This was the last of the great airship disasters; it was preceded by the crashes of the British R38 in 1921 (44 dead), the US airship Roma in 1922 (34 dead), the French Dixmude in 1923 (52 dead), the British R101 in 1930 (48 dead), and the US Akron in 1933 (73 dead). (Source Wikipedia) f k h d 7 hrs 6 pcs 0.15 mm 0.40 mm PLA 70 g MK3/S Toys & Games > Vehicles airship famous friedrichshafen hindenburg lakehurst lz129 model scale zeppelin luftship large However, it should even reach 4-5% infill The assembly is quite simple. You should only pay attention to the exact course of the lines. -

Airborne Arctic Weather Ships Is Almost Certain to Be Controversial

J. Gordon Vaeth airborne Arctic National Weather Satellite Center U. S. Weather Bureau weather ships Washington, D. C. Historical background In the mid-1920's Norway's Fridtjof Nansen organized an international association called Aeroarctic. As its name implies, its purpose was the scientific exploration of the north polar regions by aircraft, particularly by airship. When Nansen died in 1930 Dr. Hugo Eckener of Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin Company suc- ceeded him to the Aeroarctic presidency. He placed his airship, the Graf Zeppelin, at the disposal of the organization and the following year carried out a three-day flight over and along the shores of the Arctic Ocean. The roster of scientists who made this 1931 flight, which originated in Leningrad, in- cluded meteorologists and geographers from the United States, the Soviet Union, Sweden, and, of course, Germany. One of them was Professor Moltschanoff who would launch three of his early radiosondes from the dirigible before the expedition was over. During a trip which was completed without incident and which included a water land- ing off Franz Josef Land to rendezvous with the Soviet icebreaker Malygin, considerable new information on Arctic weather and geography was obtained. Means for Arctic More than thirty years have since elapsed. Overflight of Arctic waters is no longer his- weather observations toric or even newsworthy. Yet weather in the Polar Basin remains fragmentarily ob- served, known, and understood. To remedy this situation, the following are being actively proposed for widespread Arctic use: Automatic observing and reporting stations, similar to the isotopic-powered U. S. Weather Bureau station located in the Canadian Arctic. -

Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lift in Aerostats 1783 to 1883

Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research Volume 13 Number 1 JAAER Fall 2003 Article 1 Fall 2003 Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lift in Aerostats 1783 to 1883 Thomas Forenz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/jaaer Scholarly Commons Citation Forenz, T. (2003). Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lift in Aerostats 1783 to 1883. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.15394/ jaaer.2003.1559 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forenz: Assessing the Evolution of the Airborne Generation of Thermal Lif Thermal Lift ASSESSING THE EVOLUTION OF THE AIRBORNE GENERATION OF THERMAL LIFT IN AEROSTATS 1783 TO 1883 Thomas Forenz ABSTRACT Lift has been generated thermally in aerostats for 219 years making this the most enduring form of lift generation in lighter-than-air aviation. In the United States over 3000 thermally lifted aerostats, commonly referred to as hot air balloons, were built and flown by an estimated 12,000 licensed balloon pilots in the last decade. The evolution of controlling fire in hot air balloons during the first century of ballooning is the subject of this article. The purpose of this assessment is to separate the development of thermally lifted aerostats from the general history of aerostatics which includes all gas balloons such as hydrogen and helium lifted balloons as well as thermally lifted balloons. -

LZ 129 Hindenburg from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia (Redirected from Airship Hindenburg)

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history LZ 129 Hindenburg From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Airship Hindenburg) Navigation "The Hindenburg" redirects here. For other uses, see Hindenburg. Main page LZ 129 Hindenburg (Luftschiff Zeppelin #129; Registration: D-LZ 129) was a large LZ-129 Hindenburg Contents German commercial passenger-carrying rigid airship, the lead ship of the Hindenburg Featured content class, the longest class of flying machine and the largest airship by envelope volume.[1] Current events It was designed and built by the Zeppelin Company (Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH) on Random article the shores of Lake Constance in Friedrichshafen and was operated by the German Donate to Wikipedia Zeppelin Airline Company (Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei). The airship flew from March 1936 until destroyed by fire 14 months later on May 6, 1937, at the end of the first Interaction North American transatlantic journey of its second season of service. Thirty-six people died in the accident, which occurred while landing at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in Help Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. About Wikipedia Hindenburg was named after the late Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), Community portal President of Germany (1925–1934). Recent changes Contact page Contents 1 Design and development Hindenburg at NAS Lakehurst Toolbox 1.1 Use of hydrogen instead of helium Type Hindenburg-class 2 Operational history What links here airship 2.1 Launching and trial flights Related changes Manufacturer -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. AJP Taylor, English History, 1914–1945 (Oxford: OUP, 1965), p. 522. 2. For sentiments similar to Taylor’s, expressed in the memoirs of several pro- tagonists and makers of British foreign policy during the Second World War, see Major General Sir Francis de Guingand, Operation Victory (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1947), p. 49; Bernard Fergusson, The Trumpet in the Hall, 1930–1958 (London: Collins, 1970), pp. 81–5; Lord Ismay, The Mem- oirs of General the Lord Ismay (London: Heinemann, 1960), pp. 322, 330–1; Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, Diplomat in Peace & War (London: John Murray, 1949), pp. 203–4; Arthur S Gould Lee, Special Duties – Reminis- cences of a Royal Air Force Staff Officer in the Balkans, Turkey and the Middle East (London: S Low, Marston & Co, 1946), p. 28; Sir John Lomax, Diplo- matic Smuggler (London: A Barker, 1965), pp. 245–6; Geoffrey Thompson, Front-Line Diplomat (London: Hutchinson, 1959), p. 167. 3. For a concise account of the nature of this material, and the means by which it was gathered, see Robin Denniston, ‘Diplomatic Eavesdropping, 1922–44: A New Source Discovered,’ Intelligence & National Security 10:3 (1995), 423–48. 4. Robin Denniston, Churchill’s Secret War: Diplomatic Decrypts, the Foreign Office and Turkey, 1942–44 (Stroud: Sutton, 1997). 5. There is a complete run of diplomatic intercepts dating back to the early 1920s, although the period June–December 1938 is missing. 6. John Robertson, Turkey & Allied Strategy, 1941–45 (New York: Garland, 1986). 7. Gabriel Gorodetsky, Grand Delusion – Stalin & the German Invasion of Russia (London: Yale University Press, 1999). -

The Dams Raid

The Dams Raid An Air Ministry Press Release, dated Monday, 17th May 1943, read as follows: In the early hours of this (Monday) morning a force of Lancasters of Bomber Command led by Wing Commander G. P. Gibson, D.S.O, D.F.C., attacked with mines the dams at the Möhne and Sorpe reservoirs. These control two-thirds of the water storage capacity of the Ruhr basin. Reconnaissance later established that the Möhne Dam had been breached over a length of 100 yards and that the power station below had been swept away by the resulting floods. The Eder Dam, which controls head waters of the Weser and Fulda valleys and operates several power stations, was also attached and was reported as breached. Photographs show the river below the dam in full flood. The attacks were pressed home from a very low level with great determination and coolness in the face of fierce resistance. Eight of the Lancasters are missing. That short statement lacked some of the secret details and the full human story behind one of the most famous raids in the history of the Royal Air Force. It is the real story of the Dambusters. The story of the “bouncing bomb” designer Barnes Wallis and 617 Squadron is heavily associated with the film, starring Michael Redgrave as Dr Barnes Wallis and Richard Todd as Wing Commander Guy Gibson – and featuring the Dambusters March, the enormously popular and evocative theme by Eric Coates. The film opened in London almost exactly twelve years after the events portrayed. The main detail of the raid which was not fully disclosed until much later was the true specification of the bomb, details which were still secret when the film was made. -

Don Piccard 50 Years & BM

July 1997 $3.50 BALLOON LIFE EDITOR MAGAZINE 50 Years 1997 marks the 50th anniversary for a number of important dates in aviation history Volume 12, Number 7 including the formation of the U.S. Air Force. The most widely known of the 1947 July 1997 Editor-In-Chief “firsts” is Chuck Yeager’s breaking the sound barrier in an experimental jet—the X-1. Publisher Today two other famous firsts are celebrated on television by the “X-Files.” In early Tom Hamilton July near the small southwestern New Mexico town of Roswell the first aliens from outer Contributing Editors space were reported to have been taken into custody when their “flying saucer” crashed Ron Behrmann, George Denniston, and burned. Mike Rose, Peter Stekel The other surreal first had taken place two weeks earlier. Kenneth Arnold observed Columnists a strange sight while flying a search and rescue mission near Mt. Rainier in Washington Christine Kalakuka, Bill Murtorff, Don Piccard state. After he landed in Pendelton, Oregon he told reporters that he had seen a group of Staff Photographer flying objects. He described the ships as being “pie shaped” with “half domes” coming Ron Behrmann out the tops. Arnold coined the term “flying saucers.” Contributors For the last fifty years unidentified flying objects have dominated unexplainable Allen Amsbaugh, Roger Bansemer, sighting in the sky. Even sonic booms from jet aircraft can still generate phone calls to Jan Frjdman, Graham Hannah, local emergency assistance numbers. Glen Moyer, Bill Randol, Polly Anna Randol, Rob Schantz, Today, debate about visitors from another galaxy captures the headlines. -

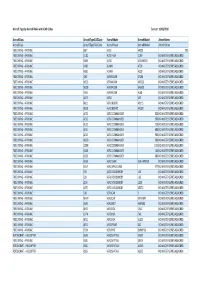

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016

Aircraft Type by Aircraft Make with ICAO Codes Current 10/08/2016 AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries AircraftClass AircraftTypeICAOCode AircraftMake AircraftModel AircraftSeries FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AJ27 ACAC ARJ21 700 FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE CUB2 ACES HIGH CUBY NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE SACR ACRO ADVANCED NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A700 ADAM A700 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE A500 ADAM A500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE F26T AERMACCHI SF260 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M326 AERMACCHI MB326 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M308 AERMACCHI MB308 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE LA60 AERMACCHI AL60 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AAT3 AERO AT3 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB11 AERO BOERO AB115 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AB18 AERO BOERO AB180 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC52 AERO COMMANDER 520 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC50 AERO COMMANDER 500 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC72 AERO COMMANDER 720 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC6L AERO COMMANDER 680 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE AC56 AERO COMMANDER 560 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE M200 AERO COMMANDER 200 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE JCOM AERO COMMANDER 1121 NO MASTER SERIES ASSIGNED FIXED WING ‐ AIRPLANE VO10 AERO COMMANDER 100 NO MASTER -

Tk-480/481 Service Manual

800MHz/900MHz FM TRANSCEIVER TK-480/481 SERVICE MANUAL © 2011-5 PRINTED IN JA PAN SUPPLEMENT K3, K4, M4 versions B51-8977-00 (Y) PDF This service manual applies to products with A8A00001 (TK-480), B160001 (TK-481) or subsequent serial numbers. Refer to the TK-480/481 series service manual for any infor- mation which has not been covered in this manual. Knob (SEL) (K29-5232-03) Knob (VOL) (K29-5231-03) Whip antenna (T90-0636-25) : TK-480 (T90-0640-25) : TK-481 Panel assy Badge (A62-0981-04) (B43-1139-04) Knob (PTT) CONTENTS (K29-5157-03) GENERAL ....................................................2 DISASSEMBLY FOR REPAIR .....................3 PARTS LIST .................................................4 Packing PC BOARD (G53-0841-22) : K4 TX-RX UNIT (X57-5630-XX) ...................10 SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM ............................14 Cabinet assy (A02-3659-23) : K4 CAUTION Illustration is TK-480/481 K4 type. When using an external power connector, please use with maximum fi nal module protec- tion of 9V. This product complies with the RoHS directive for the European market. This product uses Lead Free solder. TK-480/481 Document Copyrights Firmware Copyrights Copyright 2011 by Kenwood Corporation. All rights re- The title to and ownership of copyrights for firmware served. embedded in Kenwood product memories are reserved for No part of this manual may be reproduced, translated, Kenwood Corporation. Any modifying, reverse engineering, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- copy, reproducing or disclosing on an Internet website of the tronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, fi rmware is strictly prohibited without prior written consent of for any purpose without the prior written permission of Ken- Kenwood Corporation.