Changing Views on Vikings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes. -

Who Were the Prusai ?

WHO WERE THE PRUSAI ? So far science has not been able to provide answers to this question, but it does not mean that we should not begin to put forward hypotheses and give rise to a constructive resolution of this puzzle. Great help in determining the ethnic origin of Prusai people comes from a new branch of science - genetics. Heraldically known descendants of the Prusai, and persons unaware of their Prusai ethnic roots, were subject to the genetic test, thus provided a knowledge of the genetics of their people. In conjunction with the historical knowledge, this enabled to be made a conclusive finding and indicated the territory that was inhabited by them. The number of tests must be made in much greater number in order to eliminate errors. Archaeological research and its findings also help to solve this question, make our knowledge complemented and compared with other regions in order to gain knowledge of Prusia, where they came from and who they were. Prusian people provinces POMESANIA and POGESANIA The genetic test done by persons with their Pomesanian origin provided results indicating the Haplogroup R1b1b2a1b and described as the Atlantic Group or Italo-Celtic. The largest number of the people from this group, today found between the Irish and Scottish Celts. Genetic age of this haplogroup is older than that of the Celt’s genetics, therefore also defined as a proto Celtic. 1 The Pomerania, Poland’s Baltic coast, was inhabited by Gothic people called Gothiscanza. Their chronicler Cassiodor tells that they were there from 1940 year B.C. Around the IV century A.D. -

Scripta Islandica 63/2012

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 63/2012 REDIGERAD AV VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Mindy MacLeod (Melbourne) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Rune Palm (Stockholm) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SVERIGE © Författarna och Scripta Islandica 2012 ISSN 0582-3234 Sättning: Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-174493 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-174493 Innehåll SILVIA HUFNAGEL, Icelandic society and subscribers to Rafn’s Fornaldar sögur nordr landa . 5 GUÐRÚN KVARAN, Nucleus latinitatis og biskop Jón Árnasons orddannelse . 29 HEIMIR PÁLSSON, Om källor och källbehandling i Snorris Edda. Tankar kring berättelser om skapelsen . 43 TRIIN LAIDONER, The Flying Noaidi of the North: Sámi Tradition Reflected in the Figure Loki Laufeyjarson in Old Norse Mythology . 59 LARS WOLLIN, Kringla heimsins—Jordennes krets—Orbis terra rum. The trans lation of Snorri Sturluson’s work in Caroline Sweden . 93 ÞORLEIFUR HAUKSSON, Implicit ideology and the king’s image in Sverris saga . 127 Recensioner OLOF SUNDQVIST, rec. av Annette Lassen, Odin på kristent per ga- ment. En teksthistorisk studie . 137 KIRSTEN WOLF, rec. av Rómverja saga, ed. Þorbjörg Helgadóttir . 141 Isländska sällskapet HEIMIR PÁLSSON & LASSE MÅRTENSSON, Berättelse om verk sam- heten under 2010 . 147 Författarna i denna årgång . 149 Icelandic society and subscribers to Rafn’s Fornaldar sögur nordrlanda SILVIA HUFNAGEL Literary criticism often focuses on authors and the production and mean- ing of literature, but tends -

Click Here to Access Copyright Information

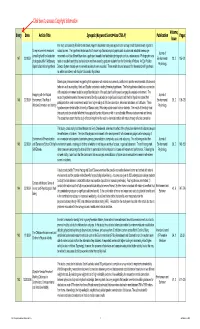

Volume, Entry Date Article Title Synopsis (Keyword Search=Use CTRL-F) Publication Pages Issue In a study conducted by Rita Berto and others, Kaplan's fascination study was applied to the concept of soft facination with regards to Do eye movements measured natural scenes. The hypothesis tested was that if shown high fascination photographs such as urban and industrial scenes, eye Journal of across high and low fascination movement would be different than when a participant viewed a low fascination photograph such as a nature scene. Photographs were 147 2/2/2009 Environmental 28, 2 185-191 photographs differ? Addressing rated on a scale from high to low fascination and then viewed by graduate students from the University of Padova. An Eye Position Psychology Kaplan's fascination hypothesis Detector System tracked eye movements and results were recorded. These results showed a support for the researcher's hypothesis as well as consistency with Kaplan's fascination hypothesis. Based upon previous research suggesting that experience with natural environments contributes to positive environmental attitudes and behaviors such as recycling, Hinds and Sparks conducted a testing three key hypotheses. The first hypothesis stated that a connection with a natural environment would be a significant indicator of the participant's willingness to engage in a natural environment. The Engaging with the Natural Journal of second hypothesis asserted that environmental identity would also be a significant indicator and the third hypothesis stated that 146 2/2/2009 Environment: The Role of Environmental 28, 2 109-120 participants from rural environments would have higher ratings of affective connection, behavioral intentions, and attitudes. -

The Development of Merchant Identity in Viking-Age and Medieval Scandinavia

Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Viking and Medieval Norse Studies The Development of Merchant Identity in Viking-Age and Medieval Scandinavia Ritgerð til MA-prófs í Viking and Medieval Norse Studies Lars Christian Benthien Kt.: 070892-4489 Leiðbeinandi: Viðar Pálsson September 2017 ABSTRACT Merchants in the pre-medieval Nordic world are not particularly well-studied figures. There is plentiful archaeological evidence for trade and other commercial activities around the Baltic and Atlantic. The people involved in trade, however, feature only rarely in the Icelandic sagas and other written sources in comparison to other figures – farmers, kings, poets, lawyers, warriors - meaning that the role of merchants, whether considered as a “class” or an “occupation,” has remained fairly mysterious. By examining a broad variety of material, both archaeological and written, this thesis will attempt to demonstrate how merchants came to be distinguished from the other inhabitants of their world. It will attempt to untangle the conceptual qualities which marked a person as a “merchant” – such as associations with wealth, travel, and adventure – and in so doing offer a view of the emergence of an early “middle class” over the course of pre-modern Nordic history. ÁGRIP Kaupmenn norræna víkingaldar hafa ekki verið nægilega rannsakaðar persónur. Það eru nægar fornleifalegaheimildir fyrir verslun og öðrum viðskiptaháttum í kringum Eystrasalthafið og Atlanshafið. Fólk í tengslum við vöruskipti, kemur mjög sjaldan fyrir í Íslendingasögum og öðrum rituðum heimildum ef borið saman við aðrar persónur, bændur, konungar, skáld, lögfræðingar, bardagamann, sem þýðir að hlutverk kauphéðna, hvort sem horft er á það sem „stétt“ eða „atvinnu“, hefur haldist leynt. Með því að fara yfir efni frá bæði fornleifaheimildum og rituðum mun þessi „ritgerð“ reyna að sýna fram á hvernig verslunarmenn fóru að aðgreina sig frá öðrum þegnum þeirra veraldar. -

Henry Rider Haggard's Nordicism?

Henry Rider Haggard’s Nordicism? When Black Vikings fight alongside White Zulus in South Africa Gilles Teulié To cite this version: Gilles Teulié. Henry Rider Haggard’s Nordicism? When Black Vikings fight alongside White Zulus in South Africa. E-rea - Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone, Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherche sur le Monde Anglophone, 2020, 18.1. hal-03225904 HAL Id: hal-03225904 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03225904 Submitted on 13 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License E-rea Revue électronique d’études sur le monde anglophone 18.1 | 2020 1. Reconstructing early-modern religious lives: the exemplary and the mundane / 2. Another Vision of Empire. Henry Rider Haggard’s Modernity and Legacy Henry Rider Haggard’s Nordicism? When Black Vikings fight alongside White Zulus in South Africa Gilles TEULIÉ Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/erea/10251 DOI: 10.4000/erea.10251 ISBN: ISSN 1638-1718 ISSN: 1638-1718 Publisher Laboratoire d’Études et de Recherche sur le Monde Anglophone Brought to you by Aix-Marseille Université (AMU) Electronic reference Gilles TEULIÉ, “Henry Rider Haggard’s Nordicism? When Black Vikings fight alongside White Zulus in South Africa”, E-rea [Online], 18.1 | 2020, Online since 15 December 2020, connection on 14 May 2021. -

Wholeness and Holiness: 8 Counting, Weighing and Valuing Silver in The

63076_kaupang_r01.qxd 06/08/08 11:01 Side 253 Wholeness and Holiness: 8 Counting,Weighing and Valuing Silver in the Early Viking Period christoph kilger This chapter examines the use of silver as a medium of payment in the Early Viking Period. Kaupang has yielded comprehensive evidence of craft activity and long-distance trade crossing economic, political and ethnic boundaries. The working hypothesis of this chapter is that exchange across such borders was undertaken outside a socially binding “sphere”, a situation that was made possible by the existence of dif- ferent forms of market trade. It is argued that there had existed standardised media of value, or “cash/money” in Kaupang, which made calculations and payment for goods possible. Such were the cir- cumstances from when Kaupang was founded at the beginning of the 9th century to the abandonment of the town sometime in the middle of the 10th. The use of “money” at Kaupang is approached from two angles. For “money” to be acceptable as an item of value depends on the one hand upon unshakable reference points that are rooted in an imaginary con- ceptual world. The value of “money” was guaranteed in terms of inalienable possessions which stabilized and at the same time initiated exchange relationships. On the other hand, money as a medium of exchange relates to a scale of calculation which legitimates and defines its exchange-value. This scale makes it possible to compare goods and put a price upon them. In this study, it is argued that in the Viking Period there were three different principles of value and payment that were materially embodied in the outer form and weight of the silver object. -

Monday 03 July 2017: 09.00-10.30

MONDAY 03 JULY 2017: 09.00-10.30 Session: 1 Great Hall KEYNOTE LECTURE 2017: THE MEDITERRANEAN OTHER AND THE OTHER MEDITERRANEAN: PERSPECTIVE OF ALTERITY IN THE MIDDLE AGES (Language: English) Nikolas P. Jaspert, Historisches Seminar, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg DRAWING BOUNDARIES: INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC SOCIETIES (Language: English) Eduardo Manzano Moreno, Instituto de Historia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid Introduction: Hans-Werner Goetz, Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg Details: ‘The Mediterranean Other and the Other Mediterranean: Perspective of Alterity in the Middle Ages’: For many decades, the medieval Mediterranean has repeatedly been put to use in order to address, understand, or explain current issues. Lately, it tends to be seen either as an epitome of transcultural entanglements or - quite on the contrary - as an area of endemic religious conflict. In this paper, I would like to reflect on such readings of the Mediterranean and relate them to several approaches within a dynamic field of historical research referred to as ‘xenology’. I will therefore discuss different modalities of constructing self and otherness in the central and western Mediterranean during the High and Late Middle Ages. The multiple forms of interaction between politically dominant and subaltern religious communities or the conceptual challenges posed by trans-Mediterranean mobility are but two of the vibrant arenas in which alterity was necessarily both negotiated and formed during the medieval millennium. Otherness is however not reduced to the sphere of social and thus human relations. I will therefore also reflect on medieval societies’ dealings with the Mediterranean Sea as a physical and oftentimes alien space. -

S+©Rheim UBAS8-Artikkel.Pdf (202.0Kb)

UniversityUBAS of Bergen Archaeological Series Nordic Middle Ages – Artefacts, Landscapes and Society. Essays in Honour of Ingvild Øye on her 70th Birthday Irene Baug, Janicke Larsen and Sigrid Samset Mygland (Eds.) 8 2015 UBAS – University of Bergen Archaeological Series 8 Copyright: Authors, 2015 University of Bergen, Faculty of Humanities, Department of Archaeology, History, Cultural Studies and Religion P.O. Box 7800 NO-5020 Bergen NORWAY ISBN: 978-82-90273-89-2 UBAS 8 UBAS: ISSN 089-6058 Editors of this book Irene Baug, Janicke Larsen and Sigrid Samset Mygland Editors of the series UBAS Nils Anfinset Knut Andreas Bergsvik Søren Diinhoff Alf Tore Hommedal Layout Christian Bakke, Communication division, University of Bergen Cover: Arkikon, www.arkikon.no Print 07 Media as Peter Møllers vei 8 Postboks 178 Økern 0509 Oslo Paper: 130 g Galerie Art Silk H Typography: Adobe Garamond Pro and Myriad Pro Helge Sørheim The First Norwegian Towns Seen on the Background of European History New archaeological finds and new research have given us a better understanding of the question about the revitalisation of the economic life and emergence of towns in Europe after the Dark Ages following the fall of the Roman Empire in AD 476. Among other things, the Pirenne Thesis ‘Without Islam, the Frankish Empire would have probably never existed, and Charlemagne, without Muhammad, would be inconceivable’ (Pirenne 1939) is again brought into light. In this paper, I will give an account of this and discuss the emergence of centralisation and subsequent urbanism. The actual span of time in Norway will be the Viking Period and the early Middle Ages (c. -

Christian Keller Furs, Fish and Ivory – Medieval Norsemen at the Arctic Fringe

1 SUBMISSION OF PAPER TO THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC (JONA) Christian Keller Furs, Fish and Ivory – Medieval Norsemen at the Arctic Fringe DECLARATION: This paper was originally written after a discussion at a conference in Aberdeen in 2004, and was submitted for publication in the Proceedings of that conference in 2005. For reasons unknown to me, the Proceedings were never published, but the manuscript had been submitted and I needed a confirmation that I could submit it for publication elsewhere. This confirmation was finally received this fall (September 2008). The text has now been upgraded and relevant literature published since 2005 added, hopefully making it a completely up-to-date paper suited for publication. All the illustrations have been drawn by me. CONTENTS The paper sees the Norse colonization of Greenland and the exploratory journeys on the Canadian East Coast as resulting from an adaptation to the European luxury market for furs and ivory. The Norse expansion into the Western Arctic is compared to the Norse expansion into the territories of the Sámi and Finnish hunter-gatherers North and East of Scandinavia. The motivation for this expansion was what is often called the coercion-and- extortion racket, aimed at extracting furs from the local tribes (called “taxation”) for the commercial markets in Western Europe and in the Middle East. The Norse adventures in the West Atlantic are seen as expressions of the same economic strategy. Icelanders were, after all, quite familiar with the Norse economic activities North and East of Scandinavia. This comparative approach is original, and it makes the Norse expansion in the West Atlantic appear less exotic and more “in character with the Norse” than normally expressed in the academic literature. -

The Saint and the Wry-Neck: Norse Crusaders and the Second Crusade

Pål Berg Svenungsen Chapter 6 The Saint and the Wry-Neck: Norse Crusaders and the Second Crusade During the twelfth century, a Norse tradition developed for participating in the dif- ferent campaigns instigated by the papacy, later known as the crusades.1 This tradi- tion centred on the participation in the crusade campaigns to the Middle East, but not exclusively, as it included crusading activities in or near the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean. By the mid-1150s, the tradition was consolidated by the joint crusade of Earl Rognvald Kolsson of Orkney and the Norwegian magnate and later kingmaker, Erling Ormsson, which followed in the footsteps of the earlier cru- sade of King Sigurd the Crusader in the early 1100s. The participation in the cru- sades not only brought Norse crusaders in direct contact with the most holy places in Christendom, but also the transmission of a wide range – political, religious and cultural – of ideas. One of them was to bring back a piece of the holiness of Jerusalem, by various means, in order to create a Jerusalem in the North. In 1152, a fleet of fifteen large ships from Norway, Orkney and Iceland sailed out from Orkney towards the Holy Land.2 The fleet, commanded by the earl and later saint of Orkney, Rognvald Kali Kolsson (r.1136–1158), and the Norwegian “landed man” [lenðir 1 For a general overview of the development of the crusades, see Jonathan Riley-Smith, What Were the Crusades?, fourth ed. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Norman Housley, Fighting for the Cross: Crusading to the Holy Land (New Haven–London: Yale University Press, 2008); Christopher Tyerman, God’s War: A New History of the Crusades (Cambridge MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2006). -

Late Prehistoric Societies and Burials in the Eastern Baltic

I LATE PREHISTORIC SOC]ETIES AND BURIALS IN THE EASTERN BALTIC O MARIKA MAGI 3 o c c Ihen.|ic|c.1el|s*ilhhU'i.L.NlodNhdllfra11)'!a.iLdregionsi|l1rccl\lc|nBl||it.ct I ofl.atc P.chi\(r1. so.icr! Sorirl anal!s.\- \hich up ro rcccnr rinrcs \!c!c lrcdonriDlnrly bascd on \anren sources rnd c\o- luron.q $ nrso l-rl' itrl, itrg. sug!.sr solrcs hat dilTerenr $cirl syeunslnr rl'. .u lrrrlh dn cr\eregions of rhccasrcflr B.lr ic. rlo\c\cr. al lihl ghD.e.rhis crnno' bc s.cn in rh. .rcl.eologic.l c\ nhncc.itrchdirtg bur'als. TIe dncusnln in rhisrniclc subjecrs{mc prnicuhr lidrrtrc\ofburialcusroms 'o closcrconsiddarnnr rcprc\en'arncncs- collccrne \e6us indi\idurl arrnudcs.lnd g.nd.r rsfccrs Thc rcn'hssuegen drar socieries \cr hi*.rdricrl borhiD tlie southemand northcnr psrls ol' rhecancrn R,lrir. nurpo\cr \.s lringed in dilIercnrNals Ker \ords: Prchlsrorien)cicrics. burials, L.le lronAgc. Somcthcofclical spects porvcr.,^ elrcts Lrndconshrctions tend to have an ac- tunl corinrcrcixl uluc. bcsidcsthe ritual significancc. The signilicrncc ol gr.rv.s cannot be overeslinalcd rvhcnthcy rrc dcpositedin a gravc.$ hich rvcrcnol nor in easlBallic rch cology.lispccially in Estoniaand maily Lrrrilablcro nrostol the populattun(Nliigi 2002. Lanja. Latc Ir(n Age ccrnctlriesare abundanrlysup- p.81I).Wc rrrry conclrde thar thc clidcnce from buri plicd \rrh grale Soods,urrd ha\e beenquilc thorough Jl. tlLr.trr.,hurJJnrl).quipFd \irI anelacr\nornr, I) cicararcd. Ho\cvcl: rhc archacologicalc\idence to lhe cxislcnccol a social elite. shile the abscnceol' in rhcsc burial tln.cs hns succccdcdonlv to a limired conspicuousburials.