Wholeness and Holiness: 8 Counting, Weighing and Valuing Silver in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

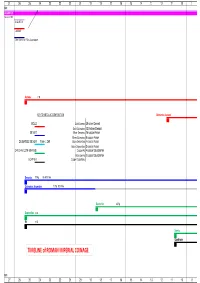

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

Changing Views on Vikings

Tette Hofstra Changing views on Vikings n this article1 changing views, not only of Viking activities, but also of the etymology and meaning of the word viking will be I discussed. Particular attention will be paid to the Netherlands. Outside Scandinavia, post-mediaeval interest in Old Scandinavian culture including Vikings arose in England at the end of the seventeenth century and France in the middle of the eighteenth century. Other countries followed suit, and this ultimately led to the incorporation of the word viking into Modern Dutch. The Modern Dutch word viking (also vikinger, wiking, wikinger) was introduced from German or English;2 the earliest entry in the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal, the large Dictionary of the Dutch Language, is from the year 1835. Both in German and in English, the word had been reintroduced in the beginning of the nineteenth century;3 in German the word begins with w- (Wiking), 1 An earlier version of this article was heard in the conference ‘North by Northwest. Scandinavia and North Western Europe: Exchange and Integration, 1600-2000’, held in Groningen from 24 until 26 November 1998. I thank those who commented on the original paper, especially Alan Swanson (Groningen). 2 Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal XXI. ’s-Gravenhage & Leiden 1971, cols. 660-662, col. 660: “niet rechtstreeks, maar via het Hd., wellicht ook het Eng., ontleend.” [‘borrowed, not directly, but through High German, maybe also English’]. 3 Cf. The Oxford English Dictionary. Second Edition XIX. Oxford 1989, p. 628: © TijdSchrift voor Skandinavistiek vol. 24 (2003), nr. 2 [ISSN: 0168-2148] 148 TijdSchrift voor Skandinavistiek in English several spellings were used, e.g. -

Sniðmát Meistaraverkefnis HÍ

MA ritgerð Norræn trú Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell Október 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view Caroline Elizabeth Oxley Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í Norrænni trú Leiðbeinandi: Terry Adrian Gunnell 60 einingar Félags– og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Október, 2019 Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA-gráðu í Norrænni trú og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Caroline Elizabeth Oxley, 2019 Prentun: Háskólaprent Reykjavík, Ísland, 2019 Caroline Oxley MA in Old Nordic Religion: Thesis Kennitala: 181291-3899 Október 2019 Abstract Að hitta skrímslið í skóginum: Animal Shape-shifting, Identity, and Exile in Old Norse Religion and World-view This thesis is a study of animal shape-shifting in Old Norse culture, considering, among other things, the related concepts of hamr, hugr, and the fylgjur (and variations on these concepts) as well as how shape-shifters appear to be associated with the wild, exile, immorality, and violence. Whether human, deities, or some other type of species, the shape-shifter can be categorized as an ambiguous and fluid figure who breaks down many typical societal borderlines including those relating to gender, biology, animal/ human, and sexual orientation. As a whole, this research project seeks to better understand the background, nature, and identity of these figures, in part by approaching the subject psychoanalytically, more specifically within the framework established by the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung, as part of his theory of archetypes. -

Who Were the Prusai ?

WHO WERE THE PRUSAI ? So far science has not been able to provide answers to this question, but it does not mean that we should not begin to put forward hypotheses and give rise to a constructive resolution of this puzzle. Great help in determining the ethnic origin of Prusai people comes from a new branch of science - genetics. Heraldically known descendants of the Prusai, and persons unaware of their Prusai ethnic roots, were subject to the genetic test, thus provided a knowledge of the genetics of their people. In conjunction with the historical knowledge, this enabled to be made a conclusive finding and indicated the territory that was inhabited by them. The number of tests must be made in much greater number in order to eliminate errors. Archaeological research and its findings also help to solve this question, make our knowledge complemented and compared with other regions in order to gain knowledge of Prusia, where they came from and who they were. Prusian people provinces POMESANIA and POGESANIA The genetic test done by persons with their Pomesanian origin provided results indicating the Haplogroup R1b1b2a1b and described as the Atlantic Group or Italo-Celtic. The largest number of the people from this group, today found between the Irish and Scottish Celts. Genetic age of this haplogroup is older than that of the Celt’s genetics, therefore also defined as a proto Celtic. 1 The Pomerania, Poland’s Baltic coast, was inhabited by Gothic people called Gothiscanza. Their chronicler Cassiodor tells that they were there from 1940 year B.C. Around the IV century A.D. -

Coins and Medals Including Renaissance and Later Medals from the Collection of Dr Charles Avery and Byzantine Coins from the Estate of Carroll F

Coins and Medals including Renaissance and Later Medals from the Collection of Dr Charles Avery and Byzantine Coins from the Estate of Carroll F. Wales (Part I) To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Upper Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1 Days of Sale: Wednesday 11 and Thursday 12 June 2008 10.00 am and 2.00 pm Public viewing: 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Friday 6 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Monday 9 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 10 June 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 31 Price £10 Enquiries: James Morton, Tom Eden, Paul Wood, Jeremy Cheek or Stephen Lloyd Cover illustrations: Lot 465 (front); Lot 1075 (back); Lot 515 (inside front and back covers, all at two-thirds actual size) in association with 45 Maddox Street, London W1S 2PE Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Important Information for Buyers All lots are offered subject to Morton & Eden Ltd.’s Conditions of Business and to reserves. Estimates are published as a guide only and are subject to review. The actual hammer price of a lot may well be higher or lower than the range of figures given and there are no fixed “starting prices”. -

Small Change and Big Changes: Minting and Money After the Fall of Rome

This is a repository copy of Small Change and Big Changes: minting and money after the Fall of Rome. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90089/ Version: Draft Version Other: Jarrett, JA (Completed: 2015) Small Change and Big Changes: minting and money after the Fall of Rome. UNSPECIFIED. (Unpublished) Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Small Change and Big Changes: It’s a real pleasure to be back at the Barber again so soon, and I want to start by thanking Nicola, Robert and Jen for letting me get away with scheduling myself like this as a guest lecturer for my own exhibition. I’m conscious that in speaking here today I’m treading in the footsteps of some very notable numismatists, but right now the historic name that rings most loudly in my consciousness is that of the former Curator of the coin collection here and then Lecturer in Numismatics in the University, Michael Hendy. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

Scripta Islandica 63/2012

SCRIPTA ISLANDICA ISLÄNDSKA SÄLLSKAPETS ÅRSBOK 63/2012 REDIGERAD AV VETURLIÐI ÓSKARSSON under medverkan av Pernille Hermann (Århus) Mindy MacLeod (Melbourne) Else Mundal (Bergen) Guðrún Nordal (Reykjavík) Rune Palm (Stockholm) Heimir Pálsson (Uppsala) UPPSALA, SVERIGE © Författarna och Scripta Islandica 2012 ISSN 0582-3234 Sättning: Marco Bianchi urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-174493 http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-174493 Innehåll SILVIA HUFNAGEL, Icelandic society and subscribers to Rafn’s Fornaldar sögur nordr landa . 5 GUÐRÚN KVARAN, Nucleus latinitatis og biskop Jón Árnasons orddannelse . 29 HEIMIR PÁLSSON, Om källor och källbehandling i Snorris Edda. Tankar kring berättelser om skapelsen . 43 TRIIN LAIDONER, The Flying Noaidi of the North: Sámi Tradition Reflected in the Figure Loki Laufeyjarson in Old Norse Mythology . 59 LARS WOLLIN, Kringla heimsins—Jordennes krets—Orbis terra rum. The trans lation of Snorri Sturluson’s work in Caroline Sweden . 93 ÞORLEIFUR HAUKSSON, Implicit ideology and the king’s image in Sverris saga . 127 Recensioner OLOF SUNDQVIST, rec. av Annette Lassen, Odin på kristent per ga- ment. En teksthistorisk studie . 137 KIRSTEN WOLF, rec. av Rómverja saga, ed. Þorbjörg Helgadóttir . 141 Isländska sällskapet HEIMIR PÁLSSON & LASSE MÅRTENSSON, Berättelse om verk sam- heten under 2010 . 147 Författarna i denna årgång . 149 Icelandic society and subscribers to Rafn’s Fornaldar sögur nordrlanda SILVIA HUFNAGEL Literary criticism often focuses on authors and the production and mean- ing of literature, but tends -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

Byzantine Coinage

BYZANTINE COINAGE Philip Grierson Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 1999 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second Edition Cover illustrations: Solidus of Justinian II (enlarged 5:1) ISBN 0-88402-274-9 Preface his publication essentially consists of two parts. The first part is a second Tedition of Byzantine Coinage, originally published in 1982 as number 4 in the series Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection Publications. Although the format has been slightly changed, the content is fundamentally the same. The numbering of the illustrations,* however, is sometimes different, and the text has been revised and expanded, largely on the advice and with the help of Cécile Morrisson, who has succeeded me at Dumbarton Oaks as advisor for Byzantine numismatics. Additions complementing this section are tables of val- ues at different periods in the empire’s history, a list of Byzantine emperors, and a glossary. The second part of the publication reproduces, in an updated and slightly shorter form, a note contributed in 1993 to the International Numismatic Commission as one of a series of articles in the commission’s Compte-rendus sketching the histories of the great coin cabinets of the world. Its appearance in such a series explains why it is written in the third person and not in the first. It is a condensation of a much longer unpublished typescript, produced for the Coin Room at Dumbarton Oaks, describing the formation of the collection and its publication. * The coins illustrated are in the Dumbarton Oaks and Whittemore collections and are re- produced actual size unless otherwise indicated.